Robert Darch

By Andy Thatcher (14th June 2021)

AT: You’re teaching on the BA Photography at Falmouth University. How has teaching impacted on your practice?

RD: I ran a collective for young photographers (Macula) for seven years. I photographed them for my project Vale and they became a part of that work, so there’s a direct correlation between my practice and that setting, it was kind of blended in. Maybe one area is keeping up to date, aware of current trends and what’s happening in photography. You have an overview of lots of different aspects, maybe not the single area that you’re particularly interested in and I think that opens you up a bit more.

I’m teaching students in a very difficult situation, in lockdown, and they’ve got to make work and be experimental. How can I teach them and say try this and do this and then myself, not? I should embrace that myself. I’ve been taking pictures through Zoom and I was initially reticent – it’s through a computer screen and that doesn’t interest me. But I like a challenge and I’m competitive. So – can I get something that looks great and people don’t realise it’s through Zoom?

AT: How do you think photographic practice changes once placed in an academic setting?

RD: A lot of undergraduates find it difficult – they have a lot of work to do in a short amount of time. There’s this overwhelming sense of deadlines. You’ve got to be quite succinct in terms of what you’re doing, so if you’ve got quite a free-flowing art practice, then you’ve got to find a way to fit that in, which I think is quite useful in terms of working commercially or editorially, with very short time frames to make work. For me, it was OK because I’d done the BA at Newport which is a very tough course and so that was my grounding.

The justification of an idea makes practice completely different. If you’re an amateur, you’re just taking pictures of what you like. So many students want to work like William Eggleston for example – I’ll just walk around where I like and that just catches my eye, take a picture of that. But what is it that you’re doing beyond that? Academia makes you think about questions like the context of the work, the theoretical underpinning. On the one hand, that can be like a weight that’s tying you down, but it can also be helpful. Anything that I make, I ask where does this sit? What is this saying? How are people going to view this? And I also work on a series, rather than just a single picture – a body of work, rather than this slightly more free-flowing way of working.

AT: You reference your childhood a lot in interviews, and my own childhood experience of commons in Kent and Sussex is central to my current project at Woodbury Common. Why is childhood so influential to the way you make work?

RD: Childhood is about formative experiences. When you’re a child, you’re experiencing things for the first time. It has a huge psychological impact on you and who you are. I grew up on the edge of Tamworth and when I was three my Mum would just let me roam in the cornfields, and there was a big house at the end of our road, an old Georgian manor house and they had an annual fireworks party. Going feeding the horses, that feeling of freedom and exploration – that carries forward. These things I did as a child and a young adult, they carry weight and influence the work I make far more than anything contemporary, or any influence of a photographer, because these influences came along in my early twenties. When I make work now that’s more contemporary, like The Island, the melancholy from that is the melancholy from being a teenager. The emotions are from earlier even though the subject is more contemporary.

We’d holiday in Devon and one of my first conscious memories was hunting dogs on Dartmoor, and it was just so unnatural to a three-year-old. These are also memories of remembering, even at ten or eleven I was very quiet and introspective so many of my memories are of memories of those memories if that makes any sense. It’s that internalisation that I visualise in my work.

AT: There is often a melancholy in your images, sometimes a subtle use of light, sometimes an unmistakable subject as with The Island. Is this a conscious decision?

Yes. Definitely. I sometimes joke that I could describe my work as beautifully sad. I’m not a particularly sad person, but I think you tap into that melancholy you’ve experienced from life and with The Island I was referencing that sense of being a teenager and your first girlfriend breaking up with you and sitting in your room and listening to sad music, wallowing a bit. That sadness is not depression though. You’re slightly nostalgic about that intensity of feeling – being in the Midlands and it’s winter and it’s wet and it’s bleak and it’s raining and you’re just bummed out and there’s something about that. It’s not a great emotion but it’s a powerful emotion and it’s something you tap into. Because I had all those years of illness, I can easily tap into that notion of being in a room and listening to melancholic music. Music can capture melancholy so well, it really is the best medium for that. I don’t think photography can ever do that in the same way.

I’ve never been clinically depressed so for me, it’s that bookend of emotion – without the sadness you don’t know the joy. You’re melancholy and sad about what is past and what is gone – there’s a weight there. Because Vale is about being ill and losing my twenties, there’s that juxtaposition between bucolic, sublime summer landscapes and these young, beautiful people, and there’s an obvious juxtaposition with looking sad in that landscape. The work is layered. It’s carrying emotions. It’s a direct reflection of that sadness.

AT: Your work often blends the fictional and the documentary, and you’ve mentioned that you’re a frustrated filmmaker. Would you consider working with video? What can photography achieve which film cannot – and vice versa?

RD: Before I went back to do my Masters, I was working a lot with video. With Arnolfini and Spacex, I did all their video work, and a couple of music videos for local bands. I always made skateboard videos, little short videos on holidays. But photography was always my first love, and I decided to study it. I’m definitely someone who likes to work by myself as I’m confident enough to know what I’m doing – this is my work, this is my vision – and photography allows me to do that, it’s all me, there’s that selfishness. The best films happen where you’ve got one or two people who’ve got a clear vision and they’ve been left alone to make it, rather than diluted with different voices.

The advantage of film is mis-en-scene – you have sound and you have music to create atmosphere, particularly in horror, to create that tension. The Moor was in a way an attempt to create something that had that aesthetic, but you were missing the sound and the music. A way to explain the series would be to imagine it was stills from a film that doesn’t exist. I wanted to make these very striking photographs, creating images that would be like the film poster. I hadn’t seen anything similar, like an artist or a photographer working in this way and this always makes me question the validity of what I am doing. I think this is quite common.

The power of the still image is the time that you have with that image. I felt like there could’ve been video with Durlescombe, like with the threshing machine and the moving image of that working was amazing, and that could’ve easily made an interesting documentary subject, but I think it was a question of practicality. If I wanted to work in film, I wouldn’t be interested in just using the moving image like conceptual, fine art. I would want to make this big narrative, with actors, have all this staging, etc.

AT: This blend of the fictional and the documentary brings to mind Gideon Koppel’s film Sleep Furiously, set in a partly-fictionalized Welsh sheep farming community. What can an imaginative engagement with place achieve that an, ostensibly, more objective documentary approach cannot?

RD: I think the notion of documentary is outdated – this sense of what you are seeing as the viewer as the truth. A factual account is not the case. It never was documentary, it always was subjective, dependent on the creator, their motivations aesthetically, their political background, what they were trying to tell an audience. In the case of Durlescombe, that allowed me a much broader reach in terms of places and locations. The name is a place holder, a tool to collate this work in what that sounds like a real place. The work is 95% documentary. It might appear quite similar in terms of the staging to the The Moor, but nothing is staged, it’s all happening there, so I’m taking the pictures of these scenes in front of me, like the image of John in the barn just leaning down. You’re seeing things happening and then you’re capturing them. And in terms of the portraiture you’re just telling people to stop what they’re doing sometimes. I remember that excitement, particularly with the threshers, because I was there and I didn’t have that control anymore. It was often about stepping back and seeing the whole scene.

I’m photographing the Ten Tors and that’s much more documentary but I’m imbuing it with this melancholy, this heavy black and white, so there’s still a subjective narrative there. It’s truthful in a lot of ways to the Ten Tors, but a lot of days they’re walking and it’s sunny and it’s easy but I’m focussing on this young-people-versus-nature, so it’s my subjective version of the Ten Tors.

I always make work that’s layered. If it’s very straight, it’s not telling me something new or something different. There’s not enough there to engage me. Work that interests me makes me look at it and question what I’m looking at. Was this staged? Is this documentary? You’re questioning the veracity of what you’re seeing. That’s what I find interesting.

AT: What photographers have influenced you along the way? Whose work excites you currently?

RD: The work I’m drawn to is predominantly like the work I make. It’s people who are working in a similar way but differently. Like they’re picking up on similar influences, for example, myths and folklore. There’s so much photography out there. I’m drawn to work that impacts me, that draws out an emotional response, that I have this instant reaction to in terms of how it’s photographed, or in terms of how it’s presented.

Jem Southam is a critical influence. I was introduced to his work during my BA at Newport and out of the British work I was shown, in terms of landscape, it was the work I was drawn to. He was working in colour, large format. The Red River is one of my favourite photography books. It was integral in informing how I could look at the landscape as it was the first book that I had seen with a real lyrical, poetic quality; it was much more than just a series of pictures of the Red River. The work resonated with me and I knew then at twenty-one, that’s how I wanted to approach photography, with emotion, poetry and feeling. Then after moving to Exeter, I found I was living around the corner from him and was introduced to Jem.

My favourite contemporary photographer is Tereza Zelenkova. She’s a Czech photographer whose work predominately deals with myth and the landscape. Themes of the uncanny really underpins her work. Similarly, Robin Friend. He studied at Plymouth quite a few years ago with Jem and his book Bastard Countryside is really fascinating – that notion of a spoiled landscape is really interesting. Vasantha Yogananthan is a Peruvian Indian photographer. He deals a lot with his identity, photographing in India but around this idea of narrative in myth and religion. His work is sublime and complex.

AT: What other artists, writers, filmmakers and so-on have influenced your practice?

Painters like John Northcote Nash, Eric Ravillious whose subject is the English landscape. Constable would come into that too. Also Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth. It’s this beautiful sense of place and light – they’re integral to these painters.

Influences from literature are very much more from my childhood. Roald Dahl’s Danny The Champion of the World has a backdrop of poaching and pheasants in this autumnal landscape. Enid Blyton’s Famous Five is coastal, with a level of mystery and exploration. More recently, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road was an influence on The Moor, particularly the notion that you’re inhabiting this dystopian environment but there’s no explanation about the dystopia.

I talk about childhood films like Black Island and the British Film Foundation films. They wouldn’t get shown now but they made great one-hour films with real attention to light and detail. The acting was sometimes a bit ropey, but they had a huge impact on me as a young child. And also contemporary filmmakers like Wim Wenders that have crossed over into photography. His book Once was one of the early photography books I had and I’d go through it a lot looking at the pictures. His latter films weren’t so good, but his visuals and the colour in films like Million Dollar Hotel are sublime.

AT: You’ve mentioned you are a heart and not a head photographer. Can you say a bit more about that?

RD: It’s a very basic generalisation, but I want people to have a very emotional response to my work. I try to make images that provoke some kind of emotional response. I’m drawn to subjects through my own personal history and formative and emotional experiences. You have a lot of contemporary photography that’s very intellectualised. To me it doesn’t really have any aesthetic value. It can be really clinical, very much about the concept, which sounds sophisticated but it’s actually quite simplistic. A lot of that work is quite elitist and aimed at a very small audience. It’s not something that interests me. However, it can be successful when you combine a complex theoretical underpinning with sublime, aesthetically engaging images. For me, I’ve always got to be drawn into work by the image. I’ve got to have some emotional response to it. If I’m not drawn into the image, then why would I care what it’s about? That doesn’t mean the work I make isn’t layered or contextualised, but that theory is always secondary to the images for me. Often in over-intellectualised work, the images seem to be an afterthought.

AT: I find Dartmoor fascinating, particularly as it’s an entirely manmade landscape and deeply scarred. That resonated with me in The Moor. That’s not the Dartmoor most people seek and expect. What is your relationship to the Picturesque and the Sublime more typically depicting the moors?

RD: It comes down to a subjective response to it. You’ve got people like Gary Fabian Miller who’s going out and walking in a small part of the moor and then making sublime camera less pictures in his darkroom. My response is working in that Arthur Conan Doyle tradition of how the moor is viewed, this unforgiving, bleak, mysterious landscape. Also, the moors written about by Enid Blyton as this place of trepidation and mystery. It’s nice to walk on Dartmoor in the sunshine but I don’t have the same emotional response to that. I like being a bit scared, lost and excited because this is a bit mysterious. I have been following the Ten Tors recently and we’re out in the middle of the moor in thick cloud and it’s like being on another planet. It’s so unnatural, it’s unbelievable. The response I have to that captivates me. I’m fine with people taking pretty HDR pictures but to me they’re just superficial pictures of pretty landscapes, they don’t have any emotional depth. It’s always that distinction: what’s the work saying above and beyond it just being a pretty picture of a landscape. That’s what Dartmoor is for a lot of people.

When I started my Masters, I always knew I wanted to make a work about Dartmoor. I had a very intense emotional response to it from a very formative experience when I visited as a young child. I was drawn to this landscape. I questioned who had made work on Dartmoor? Was there anyone who had envisaged it how I see Dartmoor? There was Gary Fabian Miller, working with camera less photography. Chris Chapman who was making more traditional documentary work. Susan Derges who was working with camera less photography as well. And more recently Nick White has made a series on the militarisation of Dartmoor. I think it’s important to be aware of who has worked in a similar area as you.

In the end, I titled the series as The Moor because I wanted some ambiguity about the location. It’s interesting to note that recently the Black Mirror episode Metalhead was shot in some of the same places I used for The Moor, that someone with a similar dystopian idea was drawn to a similar landscape.

AT: Outside of your personal connections and photographic practice, what informs your relationships with places?

RD: When I was on the BA at Newport I was so influenced by everything from America. I’d walk around the edges of my small Midlands town and try and take pictures that looked like a Robert Adams picture, with big open landscapes and a horizon. Even though I’ve never been to America I’m so influenced by their culture, pictures, filmmaking, television and photography, it feels like I have been to America. I can imagine if I do visit, it will have such a strange familiarity.

This culture and the visual references hugely influence what I do. For example, Vale draws on these influences; some of the images are imbued with a sense of Southern Gothic, spirituality and religion.

I don’t have an academic relationship with landscape. It’s very much instinctive, that I feel like there’s some familiarity with the place. I will find a place and I’ll have an emotional response to it that’s derived from personal experience. I’m not so interested in a political landscape. Although The Island is the most political work I’ve made, it’s not really political in terms of dealing with that sense of struggle and ownership. It could just as equally have been about Covid, that melancholy and people being by themselves. Leaving Europe was the genesis, but it can work outside of that. It’s almost a precursor to the bleakness and melancholy of Covid.

AT: Finally – the inevitable question – how have you responded to Covid-19 in your photography? Has it caused a change in the way you see place and your practice?

RD: My initial plan was not to make any new work during the lockdown. I was going to catch up on editing. I started cycling again and I was regularly cycling up to a tree on the southern edge of Exeter because it was just an easy focal point for a short cycle. As I was there, I just started taking pictures.

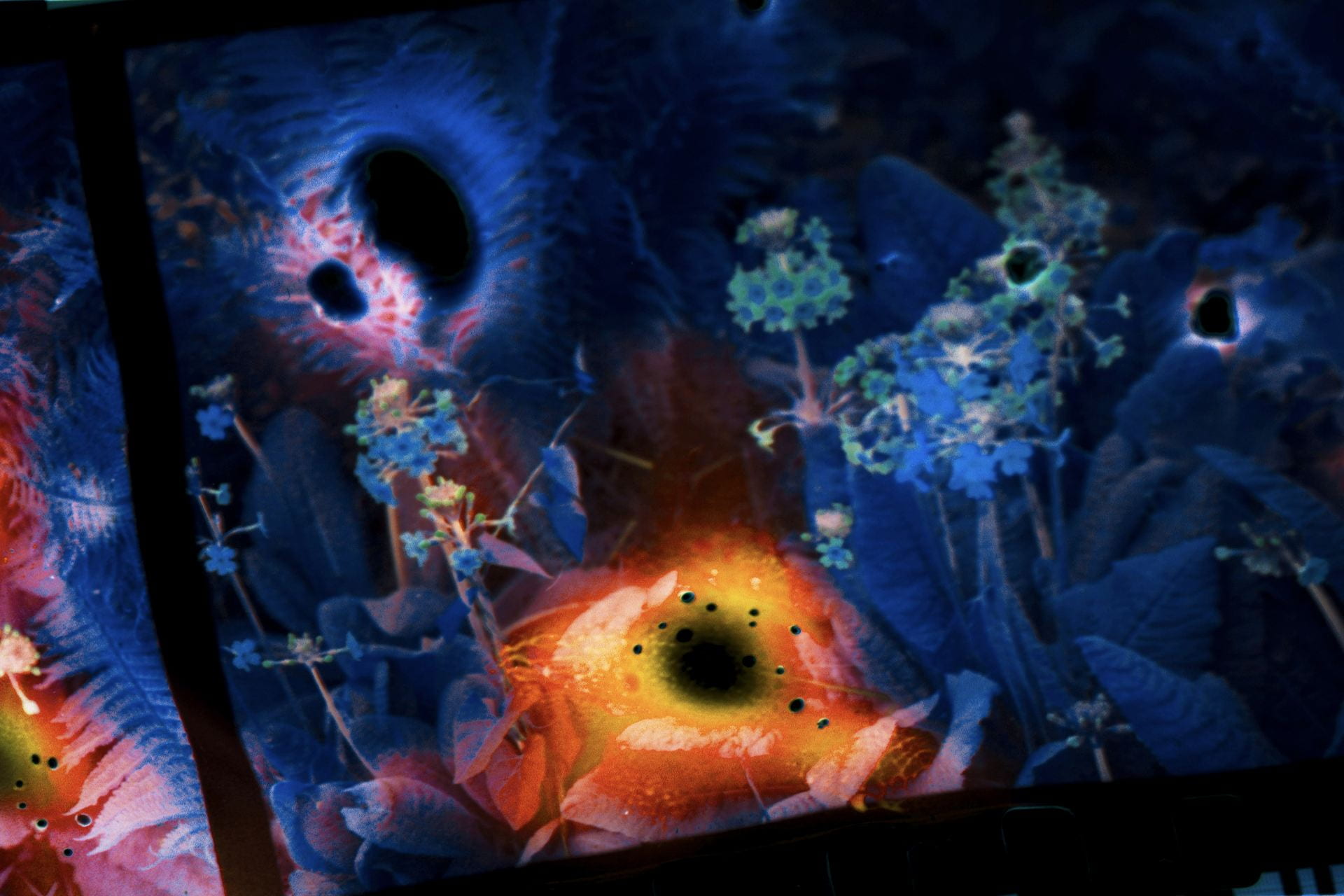

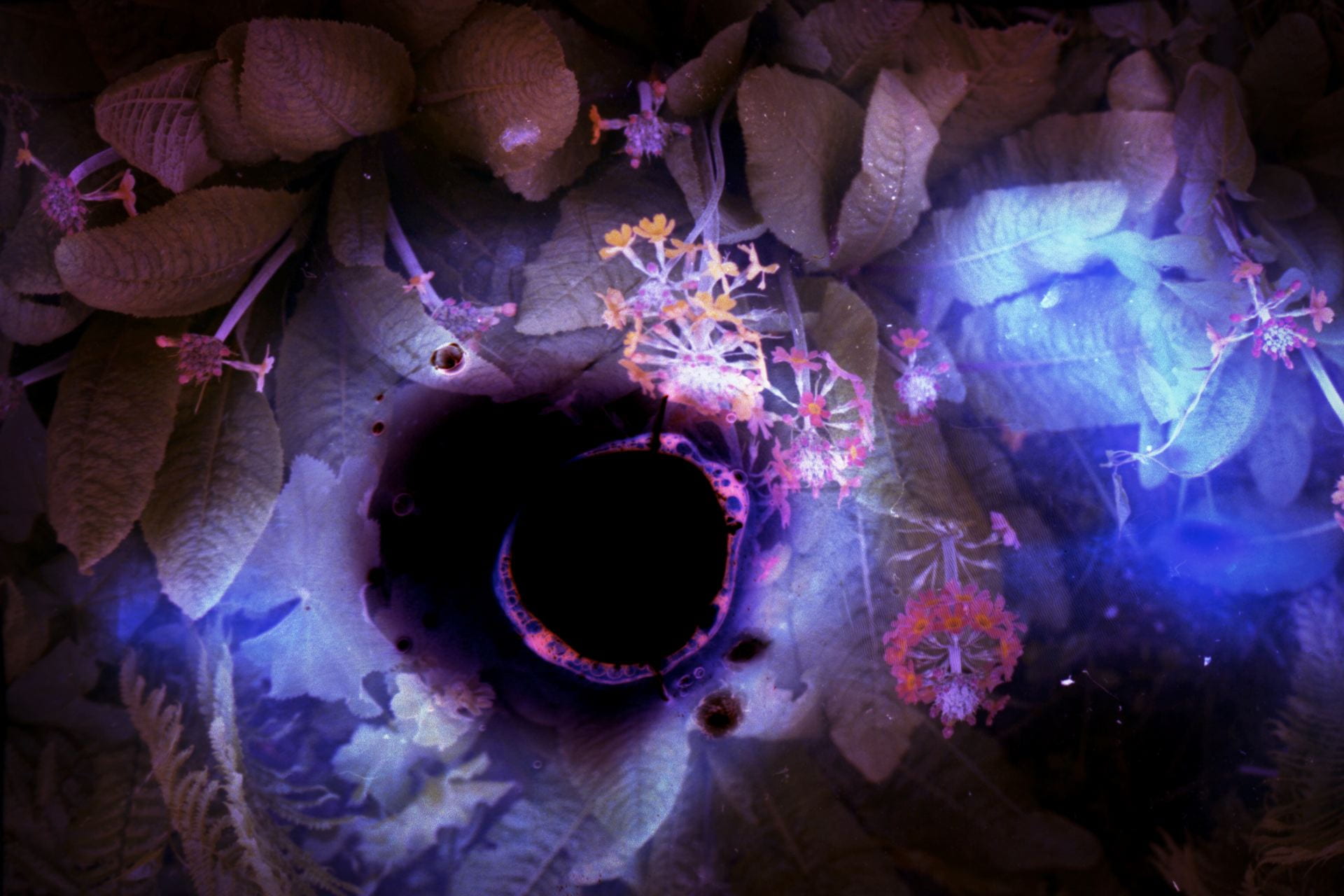

Then I got asked by a curator and a photographer to do some pictures using Zoom or a similar platform. I was initially reticent because I thought it was going to be terrible, it didn’t interest me or seem to fit into my practice. However, I’d been mulling over an idea for a year or two about referencing a sense of past Britain. Incorporating references like Agatha Christie, imagining characters that would inhabit these novels – and picturing the landscapes of the English Riviera. I had met with a young actor before lockdown to discuss taking some pictures, but this didn’t happen because of lockdown.

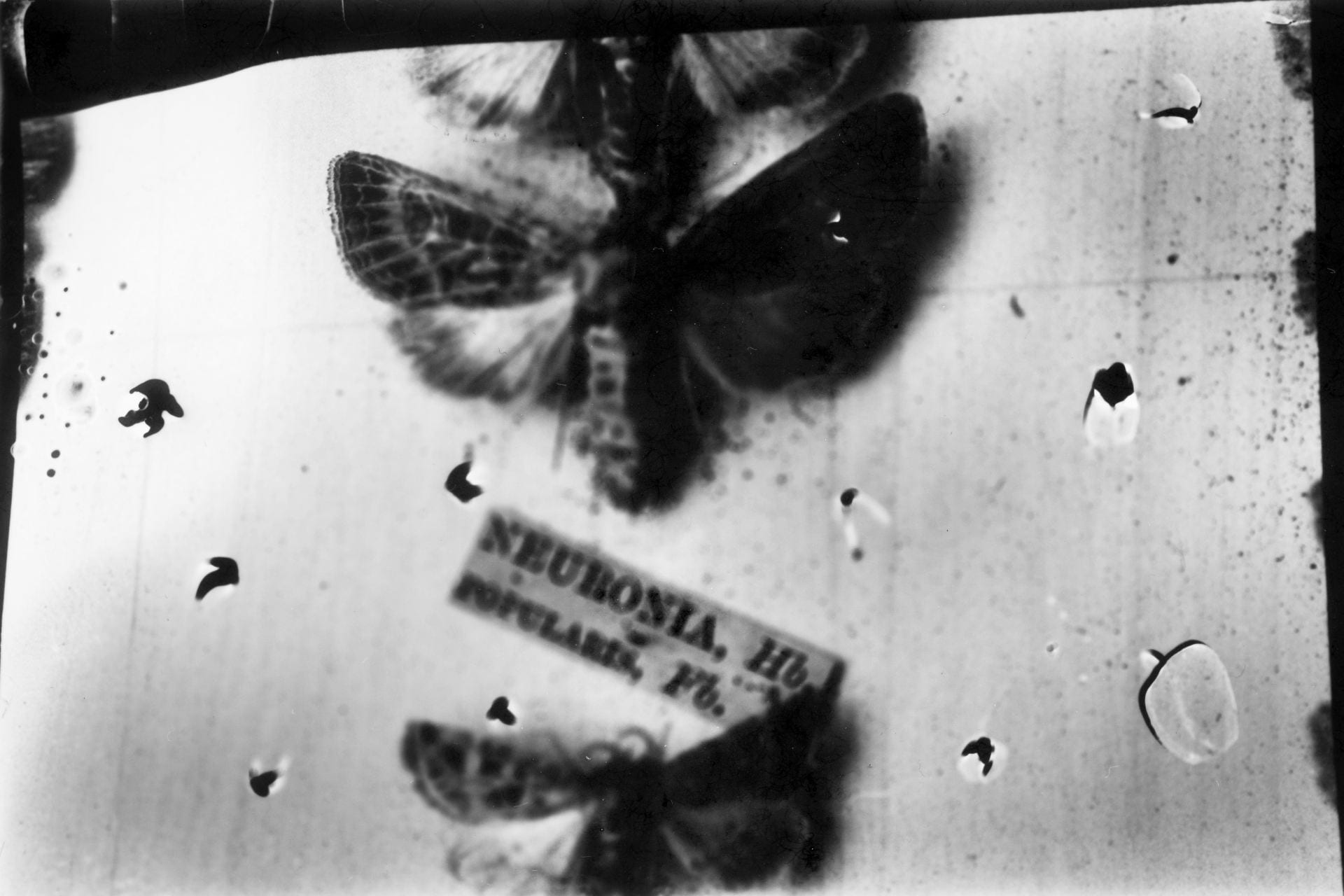

However, after a while I thought it would make sense to try and photograph her through a screen as she often emulates screen stars, so there’s a direct correlation. It’s a combination of new pictures through Zoom and archive images that I took pre-Masters when my subject matter was located more around the British coastline.

It’s really at an early stage but aesthetically, it’s sitting together nicely. The heavy use of grain is covering up the screen moiré from Zoom, but it’s also referencing something and adding an ambiguity. People are trying to work out what I’m doing – is this new, is this old?

It’s been good in terms of having a focus, still being able to photograph with somebody under lockdown. An easy way to describe the work is this love/hate relationship I have with this sense of Britishness. I like a lot of the British landscape and some of this nostalgia around the past, but I hate the small-mindedness and I hate the Brexit.

I envisage places the same as before Covid. Cycling up to the tree, making work there, was very much to do with the sense of that place and the significance of that tree for a lot of people in Exeter. The newer work is very much about place and Britishness. Covid has stopped me continuing the work on Durlescombe. For example, I’m not photographing on the farms because I don’t feel it’s particularly right, but there’s no rush and no deadline and I can carry that on at the time I feel is appropriate. It’s good to be open to new ways of working. I think that’s important to students as well not have this fixed idea of this is what I’m doing.