Good, Bad or indifferent?

By Toby Woollen (6th june 2021)

‘A combination of repeatability and access. By repeatability, I mean the ability to make exact copies of an image ad infinitum; simple laws of supply and demand dictate that the more objects there are to go around, the less fighting over them ensues, and consequently, value falls’ (Thein, 2013)

The commercial side of the ‘art’ world can be seen throughout history. During the Italian Renaissance, for example, the Popes of the Catholic Church ‘strove to make Rome the capital of Christendom while projecting it, through art, architecture, and literature, as the centre of a Golden Age of unity, order, and peace’ (Norris 2007). Artworks were commissioned by the Popes of the time in order to create a legacy for themselves and the church, which in turn helped to instil awe and wonder in the viewers. It is undeniable to say that this form of commerciality was beneficial to the art of the period though, as some of the most ubiquitous works of art were created in this time by artists who had been commissioned by the Catholic Church. Michelangelo’s painting of the Sistine Chapel ceiling was a commission by Pope Julius II in 1508 and has been both a tourist and religious attraction ever since, attracting up to 20,000 people per day in summer (Pullella 2012).

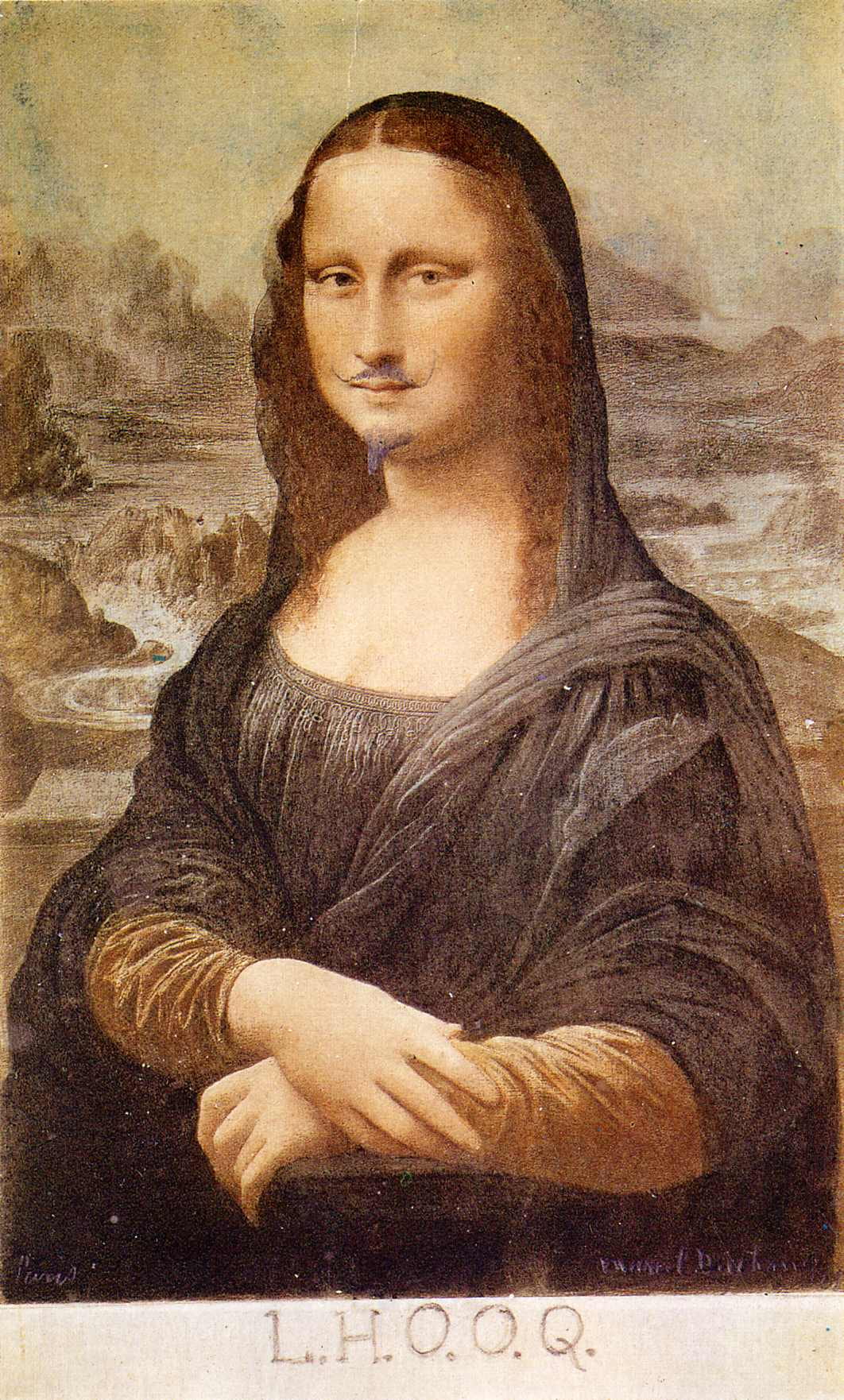

However, as the Renaissance allowed artists to look more towards Humanism rather than Catholicism, many works of art were made that did not focus on Christianity but looked at the value of human life and people instead. Some of these artworks have been commercialised more recently, Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is a good example of this. Described as ‘the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, the most parodied work of art in the world’ (Lichfield, 2005), the Mona Lisa has been reproduced countless times by clothing brands and artists alike.

Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. was not the first appropriation of the work but it drew more attention to it as critics of the time saw Duchamp’s work as ‘immoral and vulgar, even plagiaristic’ (MoMa 2021), so having a reputation such as Marcel Duchamp attached to the image of the Mona Lisa certainly elicited more attention. Perhaps more importantly however, Duchamp managed to take the work away from the commercial world and mould it back into the art world again. By drawing on a postcard of the original piece, he takes the synonymous image of the Mona Lisa ‘from the banality of reproduction and returns it to the private world of creation’ (Jones, 2001). We could say, then, that commerciality actually led to more creativity for Duchamp; he saw how Da Vinci’s painting had been commercialised and used this to his advantage.

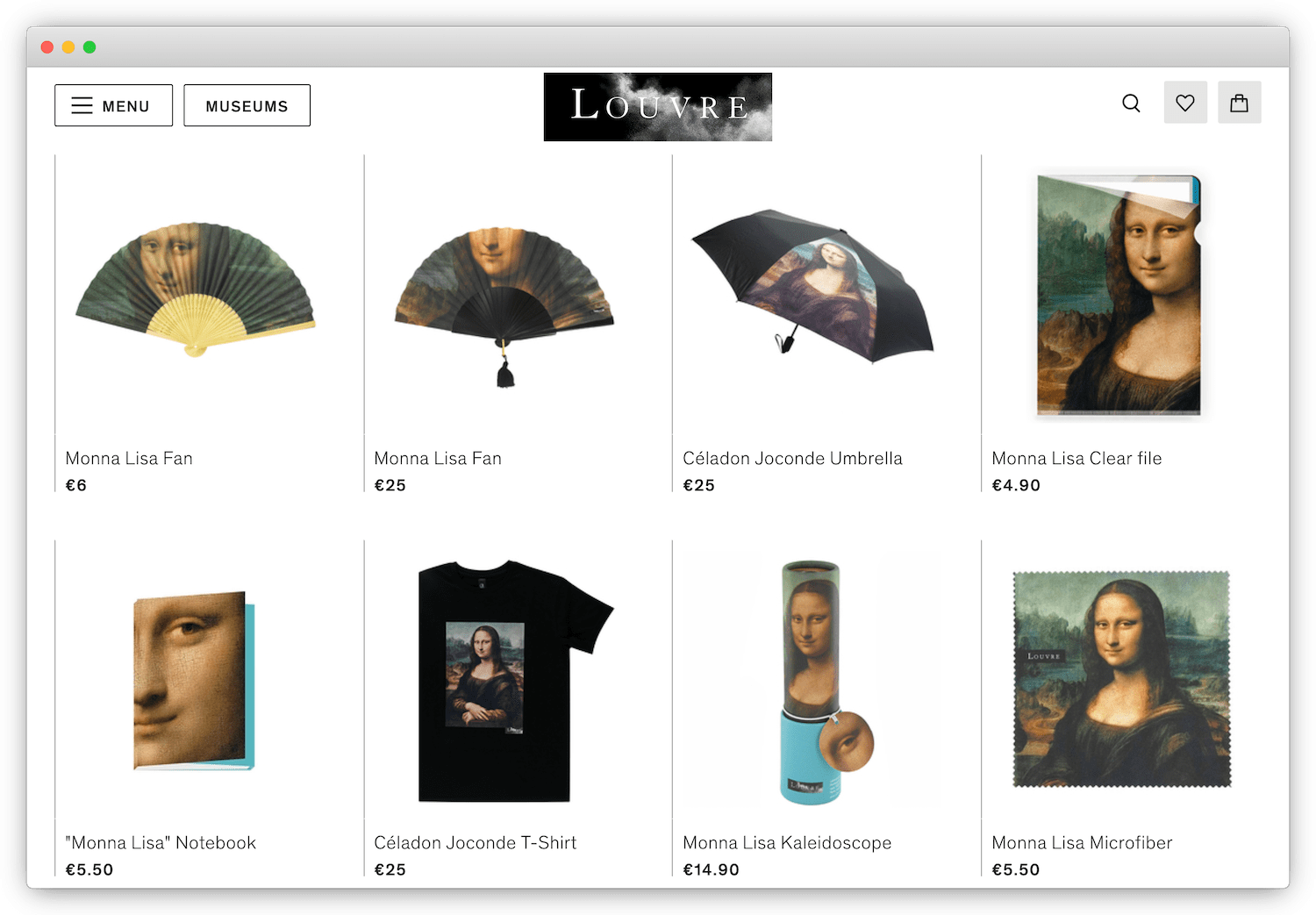

Gift shops are the ideal arenas for art to be reproduced and commercialised. This can, however, dilute the initial context of the work. When talking about Edvard Munch’s The Scream on the TalkArt podcast, Tracy Emin argues that Munch’s work was grossly misunderstood, and that what was initially a work intended to talk about the ‘never ending scream of nature’ ended up ‘being a car key ring, or a fridge magnet, or a cartoon, or a joke. There was nothing jokey about that at all’ (Emin, 2020). She went on to discuss how she has made sure that after her death she ‘will not become a nail file or a key ring’, alluding to her negative view on the way in which the commercialisation of certain works can diminish their context.

‘The context of display is an important issue because it colours our perception and informs our understanding of works of art’ (Barker, 1999, p.8)

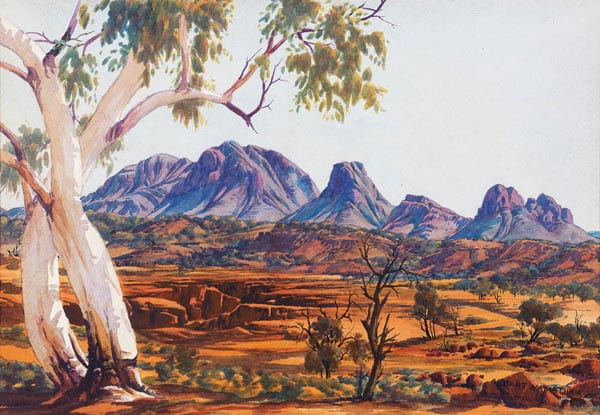

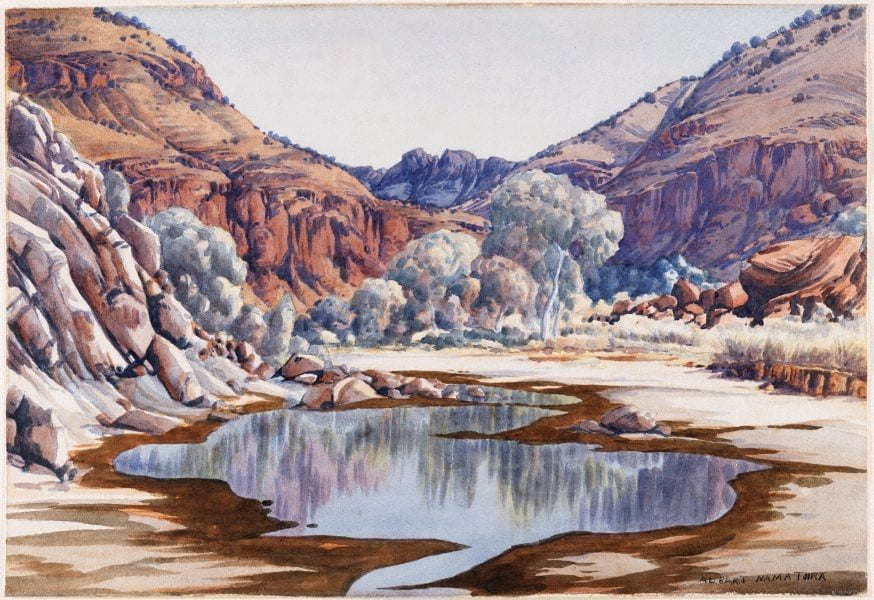

Case Study: Albert Namatjira

Albert Namatjira was born in 1902 in Hermannsburg in the Northern Territory of Australia. He was separated by the government from his parents to attend a Lutheran mission school at a young age and he soon became interested in the possibility of learning to paint. ‘Motivated by a deep attachment to his country and the possibility of a vocation that offered financial return’ (Kleinert, 2000), Namatjira expressed his interest of learning painting to Rex Battarbee, an Australian artist who in 1936 took Namatjira on expeditions as a cameleer. Battarbee lent Namatjira the materials needed in order to paint and taught him how to do so in a European style. Battarbee ‘was impressed by his evident talent’ (Kleinert, 2000) and two years later in 1938 Namatjira would hold his first solo exhibition at the Fine Art Society Gallery in Melbourne.

It is notable that it was only when Namatjira painted in a European manner that he began to gain national and international commercial attention; many people sought to buy works of art from one of the first Aboriginal painters to work in a European style. However, Namatjira, along with all other Aboriginal people in Australia, were wards of the state and were therefore disallowed from making their own legal decisions. He could not, for example, decide to travel between territories. Choices such as these would be made for him by the government and subsequently state departments of Native Affairs (Edmond 2014: 358) and because of his legal standing (or lack thereof), Namatjira was taken advantage of many times during his life by people who wanted to sell originals or copies of his work. Paintings bought for £20 may have then been marked up to as much as £100 (Edmond, 2014: 350). Whilst this may seem like a rather normal occurrence in the modern-day art market, it is important to note not only the immediacy but the lack of control Namatjira had over these deals.

It is undeniable then that commercialisation played a largely negative role in Namatjira’s artistic career. Whilst he may have created some of the most famous and beloved artworks in Australia to this date, they are outshone by the immorality of his treatment. In 1957, his wardship was finally revoked, but Edmond & Williamson (2014) propose that ‘all it meant was that he was no longer subject to the rules and regulations that so-called full-bloods had to observe and thus, from one point of view, was less an invitation to join white Australia than an excision from his own people’ (2014: 365-6). No longer being a ward of the state gave Namatjira some more freedoms, most notably a licence to buy alcohol. The commerciality of his work meant that Namatjira earned more than most other Aboriginal Australians of the time. He used his money to buy and supply alcohol to his family and friends, which he was later arrested and imprisoned for (Alexander 2014).

References

- ALEXANDER, George (2014) Tradition Today. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales. [online] Available at: <https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/artists/namatjira-albert/> [accessed 14/04/21]

- BARKER, Emma (ed.) (1999) Contemporary Cultures of Display New Haven: Yale University Press

- EDMOND, Martin and Harry WILLIAMSON (2014) Battarbee and Namatjira. Artarmon, New South Wales: Giramondo.

- EMIN, Tracy (2020) Interviewed by Russell TOVEY and Robert DIAMENT on TalkArt [online]. Available at: <https://open.spotify.com/episode/6YNglFhcrNkaJlDVhX5PXm?si=c5c7c8bfe5984905> [accessed: 09/04/21]

- GIFFARD-FORET, Paul (2018) Settling Scores: Albert Namatjira’s Legacy. Vol.41(1). Rodez: Société d’Étude des Pays du Commonwealth. [online] Available at: <https://search.proquest.com/docview/2214889737?accountid=15894&pq-origsite=primo> [accessed 24/03/21]

- JONES, Jonathan (2001) ‘L.H.O.O.Q., Marcel Duchamp (1919)’. Portrait of the Week. London: The Guardian. Available at: < https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2001/may/26/art> [accessed 12/04/21]

- KLEINERT, Sylvia (2000) Namatjira, Albert (Elea) (1902–1959). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 15. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing.

- LICHFIELD, John (2009) ‘The Moving of the Mona Lisa’. Europe. London: The Independent. Available at: < https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/moving-mona-lisa-530771.html> [accessed 12/04/21]

- Museum of Modern Art (2021) ‘Marcel Duchamp and the Readymade’. Dada. New York: MoMa. Available at: <https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/dada/marcel-duchamp-and-the-readymade/> [accessed 13/04/21]

- NORRIS, Michael (2007) ‘The Papacy during the Renaissance’. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: Metropolitan Museum. Available at: <https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pape/hd_pape.htm> [accessed 12/04/21]

- PULLELA, Phillip (2012) ‘Vatican may eventually limit Sistine Chapel visits’. Lifestyle. London: Reuters. Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-vatican-sistine-idUSBRE89U0XF20121031> [accessed 13/04/21]

Follow Toby WoOllen on Instagram