…And On Whiter Walls?

By Lizzy Tollemache (8th January 2020)

The White Gaze: it is a phrase that resonates in black American literature… The White Gaze: it traps black people in white imaginations (Grant, 2015)

Edward Said (1978) discussed this in Orientalism, a concept later referred to by Elizabeth Kaplan (1997) as the ‘Imperial Gaze’. Essentially: do we still view and construct the world through a white (eyed) perspective?

Is this white gaze still alive and well today? And, more specifically, is it the same in visual culture? Or, indeed, in exhibition culture?

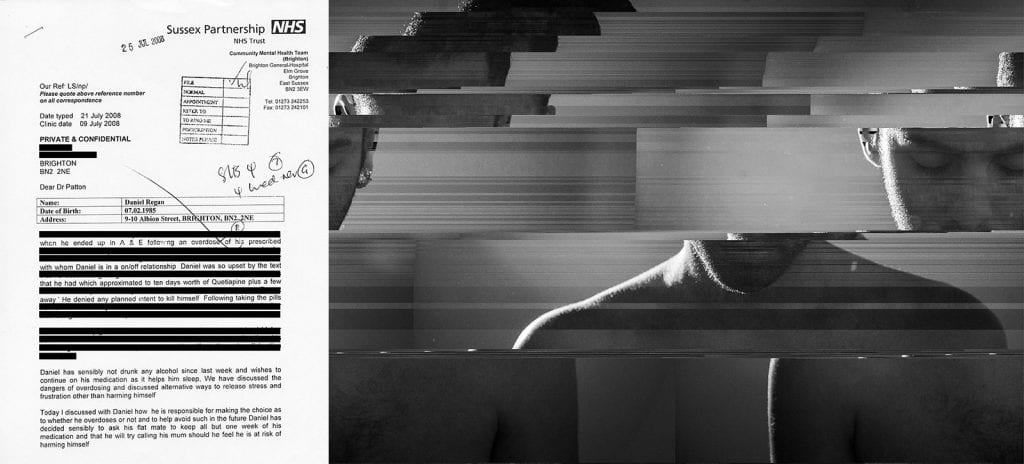

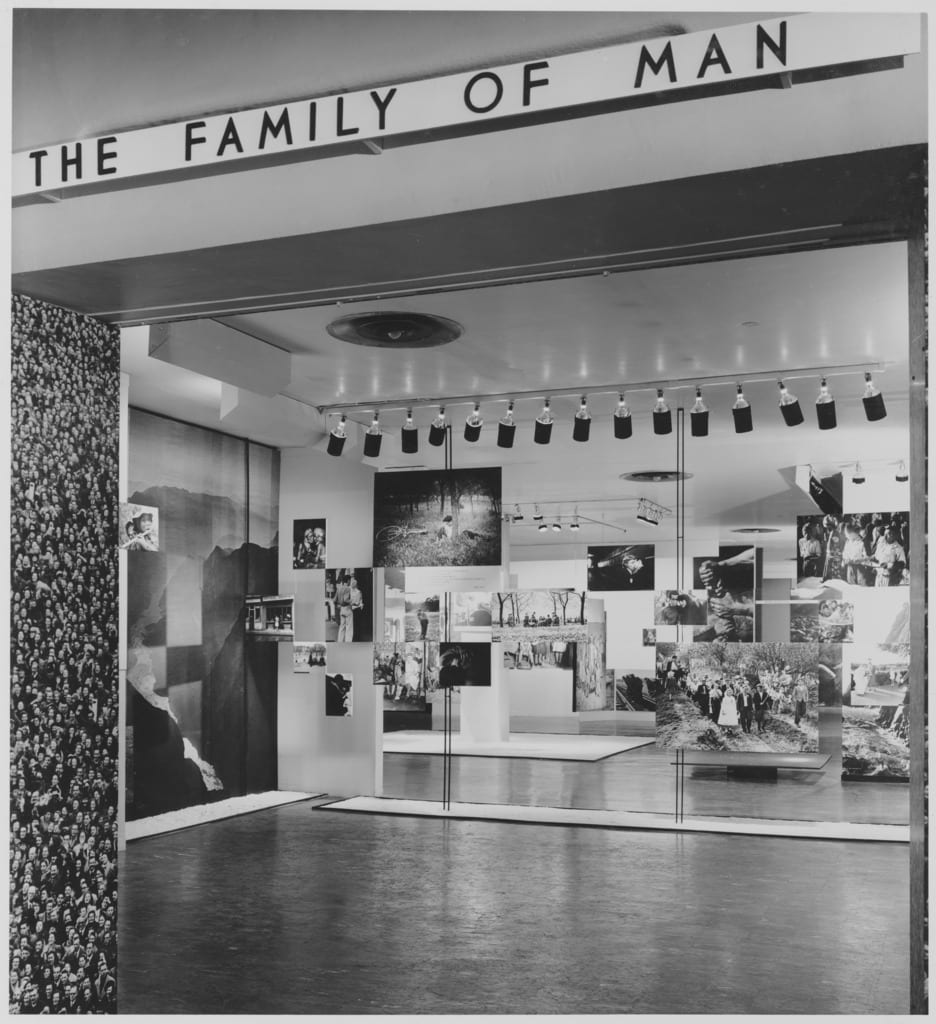

Let us first consider the Family Of Man exhibition (MoMA 1955) as a point of reference, we should still consider, if, when and how contemporary exhibitions might maintain unequal power relations within the white walls of the gallery. Are these are entitled to the same critique as acts of ‘aesthetic colonialism’? (Sekula, 1981, p.15), even of ‘universalising’ [racial] expereinces (Barthes, 2009, p.121). Do these minority voices remain ‘silenced’ by the imposed narrative of the curator? (Phillips, 1982, p.62).

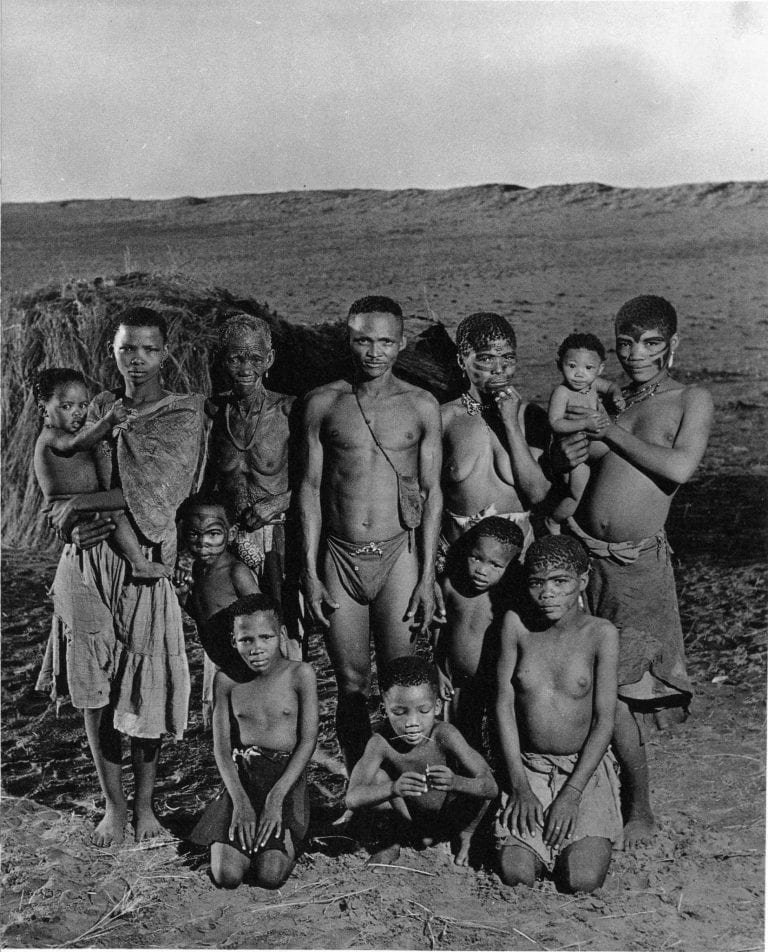

Like Phillips (1982), I view Steichen as an egocentric puppeteer; his decontexulisation of the artist’s works gave him the power to choose how photographers voices were silenced, and particularly how People of Colour (PoC) were represented, that ultimately served as this ‘instrument of cultural colonialism.’ (Sekula, 1981. p.15) Theophilus Neokonkwo (1995 in Sandeen, p.155) also furthers this point, that non-western people, were depicted as ‘social inferiors, half clothed’ as well as victims of poverty and despair – and (as such, he argues) were exploited. He goes on to discuss the way that Western peoples were presented in ‘dignified cultural states’. Sound familar? Think National Geographic.

The ignominious lack of inclusivity, out of 256 works exhibited only 12 were from non-westerners (Tīfentāle, 2018)

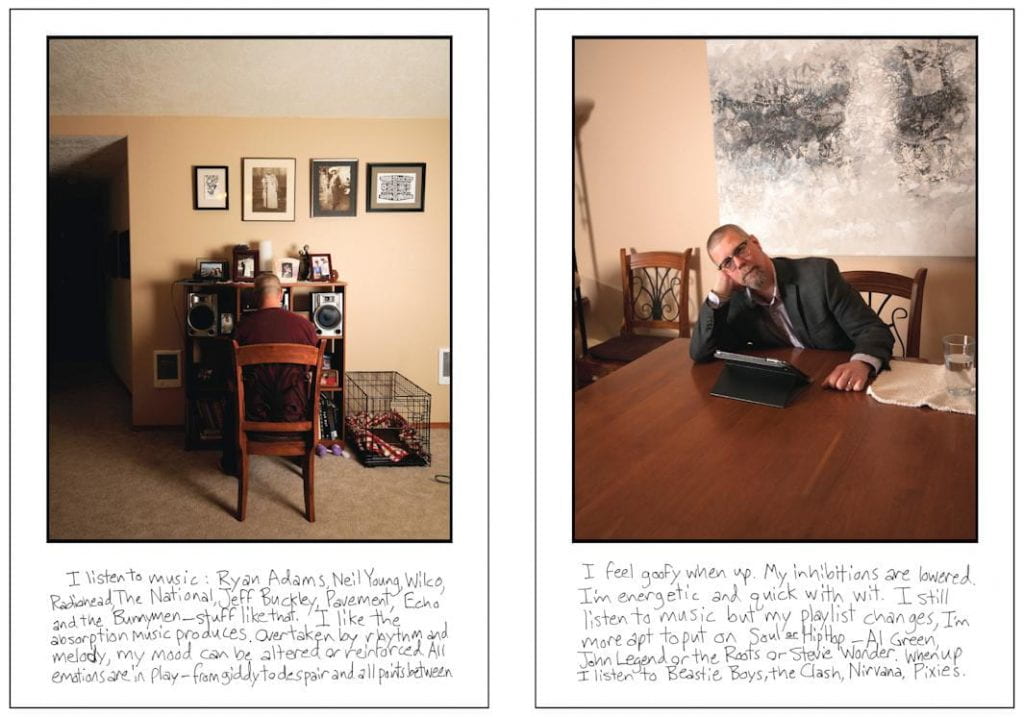

So thus, viewing essentially becomes voyeuristic. In ‘Regarding The Pain of Others’ Susan Sontag voices photography’s inability to accurately capture experiences not lived by the participant, in short, we have ‘no right to experience the suffering of others at a distance, denuded of its raw power’ (Sontag, 2004, p.73). Unequal treatment and visibility amongst the marginalised remains a prevaelent issue today. Whilst we might legitimately point the finger of blame at Western media, another might be a continuing (but shifting) exclusivity rooted deep in museum culture. Ali Meghji (2018) states cultural institutions are dominated by white consumers, that a discourse of ‘inclusion’ is promoted simply to avoid charges of racism, therefore PoC’s artwork is segregated and mainly only exhibited annually as a form of tokenism (Meghji, 2018)

‘Curatorial control has remained in the hands of white westerners.Third world writers and artists have had little say in the ways in which they were represented in these exhibitions and have only been able to react’ (Obguibe, 1999. p.158)

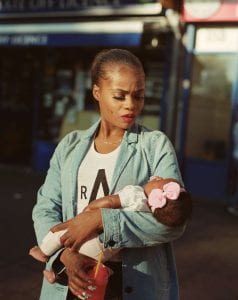

For example, the three winning photographs of 2018’s Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize depicted PoC, yet the images were captured by white photographers. Though, Khairani Barokka is interested in National Geographic – how far can we take this? Do we see again here a suggesstion that their ‘lives [are] classifiable, capturable, translatable only through the white gaze’? (Barokka, 2019). Are subjects are maintained in a position of objects of curious observation and consumption, victims of a gaze fixated on their ‘essentialist difference or desirable otherness’ (Ramirez in Ferguson et al, 1996. p.32)

‘What is often called the black soul is a white man’s artefact’ (Fanon, 1994. p.11)

Carol Duncan (1995) situates art museums as ‘species of ritual space’ to which provide a sanctuary for the contemplation of artworks (Duncan, 1995, p.5). Yet, I would argue that this sanctuary is unfairly monopolised by white practice, while this ‘ritual’ is confined to ensuring that the ‘comfort of white people, whether participants or observers, [is] paramount to anyone else’s’ (Burge, 2019). Meanwhile, Duncan goes on to suggest that a multiracial ‘dichotomy has provided a rationale for putting westerns and non western societies on a hierarchical scale’ (Duncan, 1996. p.5).

Next time you visit a group exhibition at a major gallery, count the number of minority practitoners included. It may open a whitewashed eye.

Does this so-called White Gaze really help service the views of PoC? Or, is it merely tokenism or a portrayal of ‘Otherness’ and as still fantasised objects, silencing artistic milestones and capacity to represent oneself.