Shock & Beauty / Compassion & ‘Truth’?: What Works?

By Beth Donovan (6th July 2021)

“Without photography (or a video), it has been difficult to get people to respond; the urgency and relevance of an event, its importance, and sometimes even the fact of its occurrence might be called into question.” (Ritchin 2013: 8)

Abstract

This paper explores the subject of superficial journalism and how the media use it as an excuse to shield citizens’ eyes from the visual horrors of war and conflict. It focuses on the arguments between the use of shock tactics and beautification in images, our decline in feeling compassion towards images of this nature and a case study on the way in which the Western media failed to report authentically on the Rwandan Genocide of 1994.

Drawing on the writing of Jean Baudrillard, Susan Sontag, Fred Ritchin and Susan Moeller; I shall also discuss a variety of conflicts such as Abu Ghraib, The Gulf War and the Algerian Massacre of 1997 and aim to conclude why the media censored such important images. Through the use of supportive material including critics such as Sean O’Hagan and Andy Worthington; artistic examples from photographers such as Alfredo Jaar and John Moore, I compare which of these were successful and those that were not successful in illustrating the terror of conflict in photographs.

By using a range of references, my paper argues the strategies we should be using to overcome the ever-expanding use of superficial journalism in the worldwide media. Additionally, how photojournalists such as Kenneth Jarecke and Gilles Peress are challenging the traditional media in the way in which current stories of conflict are presented.

Key Words: Shock Tactics, Compassion Fatigue, War, Photojournalism, Citizen Journalism

Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Shock Tactics, Beauty & Symbolism?

- Chapter 2: Tackling Compassion Fatigue

- Chapter 3: The Rwandan Genocide: Did the Western Media Fail?

- Conclusion

- References

- Bibliography

List of Figures

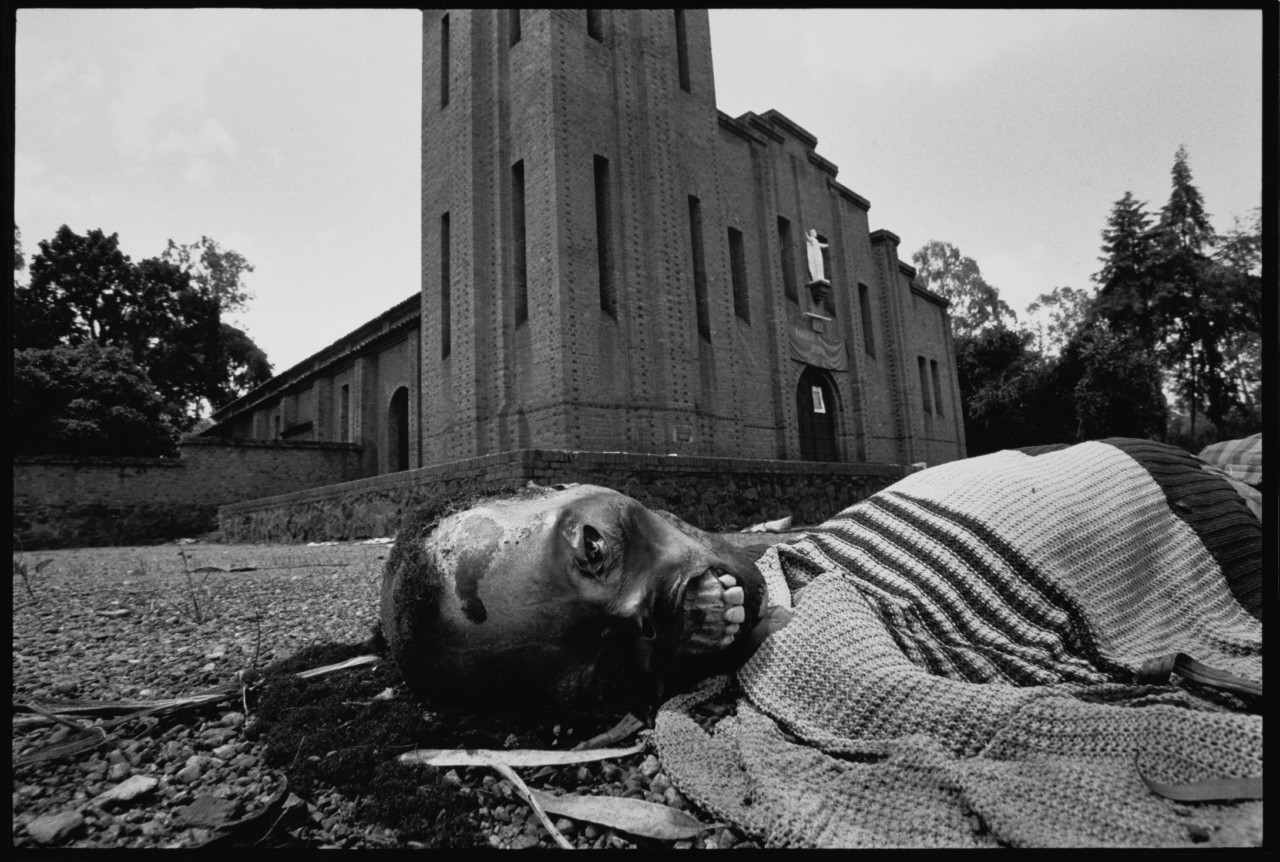

- Cover Page: JAAR, Alfredo. 1994. A Victim of Tribal Violence, Nyarubuye, Rwanda

- Figure 1: ASSOCIATED PRESS. 2003. An unidentified Abu Ghraib detainee

- Figure 2: NILUFER DEMIR / GETTY IMAGES. 2015. A Turkish police officer discovered the body of Alan Kurdi on Sept. 2, 2015, after a boat carrying refugees sank en route to the Greek island of Kos

- Figure 3: GOOGLE IMAGES. 2019. Google image search “sunset with a camel and a tank gulf war”

- Figure 4: MCCURRY, Steve. 1991. Camels, Gulf War, Kuwait

- Figure 5: JARECKE, Kenneth. 1992. An Incinerated Soldier

- Figure 6: MOSSE, Richard. 2013. from The Enclave

- Figure 7: MOSSE, Richard. 2013. from The Enclave

- Figure 8: MOSSE, Richard. 2013. from The Enclave

- Figure 9: WILLIAMSON, Michael S. 1994. Untitled from Rwanda

- Figure 10: ZAOURAR, Hocine. 1997. The Madonna of Bentalha

- Figure 11: ARANDA, Samuel. 2011. Yemen, Fighting for Change

- Figure 12: BUONARROTI, Michelangelo. 1498-1499. The Pieta (The Pity)

- Figure 13: RHONEY, Ann. 1991. United Colours of Benetton, Pieta

- Figure 14: FRARE, Therese. 1990. David Kirby’s Final Moments

- Figure 15: VELAZQUEZ, Diego. 1632. Christ Crucified

- Figure 16: THE ECONOMIST. 2004. Front Page

- Figure 17: DAILY MAIL, DAILY MIRROR, THE TIMES. 2004. Front Covers

- Figure 18: MOORE, John. 2007. The moment the bomb exploded

- Figure 19: MOORE, John. 2007. A survivor grieves at the attack scene

- Figure 20: CHADWICK, Alexander. 2007. Mobile phone image of people caught in the 7/7 bombings

- Figure 21: BROOMBERG, Adam & CHANARIN, Oliver. 2008. The Day Nobody Died

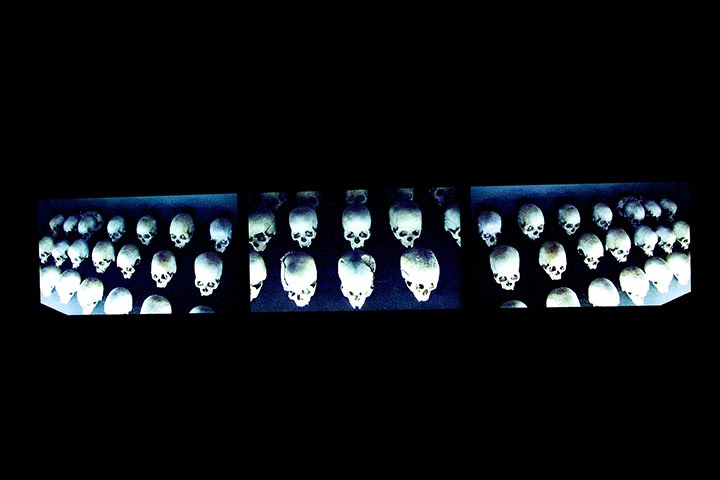

- Figure 22: PERESS, Gilles. 1994. From The Silence

- Figure 23: PERESS, Gilles. 1994. From The Silence

- Figure 24: PERESS, Gilles. 1994. From The Silence

- Figure 25: SALGADO, . 1994. Zaire

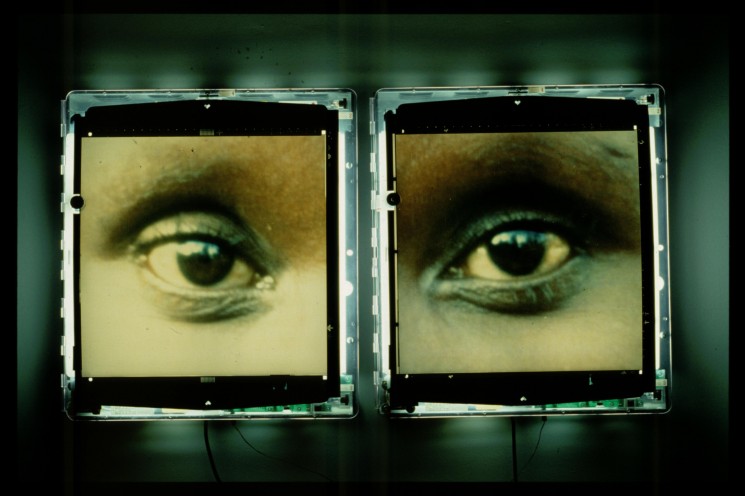

- Figure 26: JAAR, Alfredo. 2010. We Wish To Inform You That We Didn’t Know (Video Installation)

- Figure 27: JAAR, Alfredo. 1996. Eyes of Gutete Emerita

- Figure 28: JAAR, Alfredo. 2014. Eyes of Gutete Emerita Exhibition Layout

- Figure 29: WILLIAMSON, Michael S. 1994. Untitled from Rwanda

- Figure 31: WILLIAMSON, Michael S. 1994. Untitled from Rwanda

- Figure 32: JAAR, Alfredo. 1994. Untitled (Newsweek) Exhibition View

Introduction

“The increasingly malleable photograph – whether manipulated before or after the shutter’s release – is employed to fashion the world according to the intentions of the person making it, or of the institution for which it is being made.” (Ritchin 2013: 7) In my opinion, the problem with photojournalism today is that too many photographers are opting for the easy option of representing global conflicts; known as ‘superficial journalism’. Photographers are masquerading the real narrative behind their images and denying the public of the truth. Personally, I feel that if photographers are not going to reveal the blatant visuals to a wider audience when covering conflict, the use of images may as well be obsolete.

By using photographs or video when it comes to this nature of work, it can bear a beneficial effect upon society and in turn attempt to help stop the situation that is occurring. Speaking of the Abu Gharib photographs from 2004 (Figure 1) and the impact they had on society, Sontag comments: “It was the photographs that made all this ‘real’ to Bush and his associates. Up to then, there had been only words, which are easier to cover up in our age of infinite digital self-reproduction and self-dissemination, and so much easier to forget.” (Sontag 2004)

Furthermore, the silence of action from authoritative figures is still relevant today in recent global events. For example, during the European refugee crisis of 2015, officials were aware of what was happening but simply did nothing until an image of a young boy from Syria who was deceased surfaced in the media. (Figure 2) Without this image, a wider audience would have been completely oblivious to the refugee crisis.

“Connotation drawn from knowledge is always a reassuring force – man likes signs and likes them clear.” (Barthes 1977: 29) If the incorrect settings are publicised that censor the true dialogue of the event, then the inevitable happens – citizens become ignorant to their surroundings and immune to feeling compassion towards the images. As Ritchin has said here, “Without photography (or a video), it has been difficult to get people to respond; the urgency and relevance of an event, its importance, and sometimes even the fact of its occurrence might be called into question.” (Ritchin 2013: 8)

For example, the media failed in my opinion, in truly representing the conflicts of Eastern Congo, The Gulf War, Yemen (2011), Algerian Massacre of 1997 to name a few. The question of whether the use of shock tactics frightens the mass media and that is the reason for its lack thereof in photojournalism, has caused much debate in photography over the years; I discuss this further in Chapter 1 and argue that it should be more present today, especially when photographing the degradation of human actions. Conor Friedersdorf of The Atlantic has stated on this subject that “sanitised images of warfare make it easier to accept bloodless language.” (Friedersdorf 2014)

These are not narratives that should be reimagined lightly, one must feel that they were present in that terror to understand its impact; I argue that the strategy that achieves this is citizen journalism. In Chapter 2, I propose that members of society have become more immune to feeling any emotion towards photographs of conflict, due to their poor representation in the media and have fallen into a category known as compassion fatigue. Additionally, the way to combat this problem is to allow citizen journalism to have a prominent stand in media today. In Chapter Three I shall specifically discuss the Rwandan Genocide of 1994; how I feel that the Western media failed to represent the Genocide through their use of imagery. (Cover Image) Also, how American security officials instructed photojournalists to only release culturally appropriate images to the public, censoring any other images taken – thus resulting in superficial journalism.

Chapter 1: Shock Tactics, Beauty & Symbolism?

“Do the media neutralise meaning and produce unformed or informed masses, or is it the masses who victoriously resist the media by directing or absorbing all the messages that the media produce without responding to them?” (Baudrillard 1994: 84) I completely agree with Baudrillard here, it is unclear when it comes to the mass media whether it is them who is at fault for delivering images that are useless to the focus of its subject; or if it is us as an audience who are looking at all the correct photographs and information needed to put a foot forward, but yet we choose to ignore what is not on our own terrain.

During the Gulf War in Kuwait of 1991, the true visuals of the conflict were lost due to poor media coverage. Many photojournalists attended the scenes to capture the unfolding events of horror that were occurring – but only one photographer in my opinion, managed to successfully produce authentic images and that was Kenneth Jarecke. “It was one picture after another of a sunset with camels and a tank.” (Jarecke 2014) As Jarecke has said above, the Gulf War was inconsistently covered by the media (Figure 3) and photojournalists were producing photographs that simply looked more like a theatrical film than a horrific conflict. This was due to the strict rules being enforced by the American government, that any shocking photographs captured must be censored from a wider audience; the government wanted the public to “rely on the ‘mind pictures’ suggested in correspondents reports.” (Burns 1991)

Photographer Steve McCurry also illustrated the Gulf War, but I feel that McCurry’s images were illustrated in a way that describes exactly what Jarecke meant from his comment about the array of sunset, camels and tank images that surfaced from the conflict. And unfortunately, these deceptive images were surfacing much quicker for members of the public to see; images that in my opinion offered no such visual importance of the aftereffects of war and were altogether superficial. As you can see in Figure 4, the image is exactly what the caption says it is – a roaring explosion of fire behind the silhouettes of camels. It is obvious that shock tactics were not considered when McCurry took this photograph, McCurry is only beautifying war and not showing the atrocities that coincide with devastating conflicts.

In comparison to McCurry, Jarecke’s photographs were completely representative of the Gulf War and showed the inside eye of what the public were being denied of visually. (Figure 5). Jarecke’s images sparked controversy as being distasteful and dishonourable because he was specifically photographing the dead. However, Jarecke commented when being criticised that “if I don’t take pictures like these, people like my mum will think war is what they see in movies.” (Jarecke 2014) I completely agree with Jarecke here, if photojournalists do not adhere to photographing exactly what is in front of them, then their images will result in looking like McCurry’s cinematic images from the war – aesthetically newsworthy but with the wrong intentions.

The subject of war and conflict amongst photography has often been a difficult topic to approach for photographers. They can either take two paths I feel, either they decide to represent conflict with raw visualities; however this can then lead to their audience becoming desensitised to the images, especially when there is a constant outpour of these types of images. In my opinion, this would be the obvious choice though if I were to document terrorisation of a community, it bears no dishonesty. On the other hand, some photographers such as Richard Mosse, choose to opt for stunning aesthetics and this is where I feel artists who try to mirror photojournalism in their own work are failing.

Mosses’ project The Enclave displayed several images from the Democratic Republic of Congo, in what I can only describe as appearing like a fashion shoot. (Figures 6, 7 & 8) Mosse documented how 5.4 million people have died there since 1998 due to ongoing conflict; the conflicts are still happening presently as rebel groups operate to this day in Eastern Congo. He used discontinued infrared colour film that was originally used by the United States military during World War Two to highlight camouflage. Mosse’s reasoning for this was that he wanted to represent “the crisis of representation artists, photojournalists and filmmakers are confronted with when trying to depict brutality, suffering and destruction.” (Smaidment 2015)

Personally, it does not represent in my view the experience of victims who have died amongst the midst of the landscape shown. Using film that changes the colour of its surroundings in the image to bright pinks and reds, is not a valid depiction of the horror that citizens endured. The colour red may connotate the blood of the dead, but I feel the photographs do not emit anything other than visual beauty. “The first and greatest humanitarian trap is this need to simplify, if not actually lie about, the way things are in the crisis zones, in order to make the story more morally and psychologically palatable.” (Rieff 2013: 137) I agree with Rieff here, photographers such as Mosse and McCurry, continually produce work that allows the true narrative to hide behind a blanket of beauty in order for it to be deemed more acceptable for viewing.

Along with beautified images, I feel the media often uses biblical symbolism in their imagery or will refer to religion when broadcasting the news. (Figure 9) However, along with doing this, they have at times fabricated captions with images to make the story appear more dramatic – resulting in the truth of the news being pushed aside. An example of this can be found in Hocine Zaourar’s image, The Madonna of Bentalha. (Figure 10) Zaourar’s image depicted a woman crying out in despair just outside one of the hospitals within the town of Bentalha, Algeria. The Algerian Massacre of 1997 accumulated hundreds of deaths across the country, started by the Islamist guerrilla groups; they were opposing against the government and the cancellation of the elections that were due to start. The massacres had no organisation associated with them, the independent groups went from house to house, killing every man, woman, and child. Although the image had critical acclaim and benefited in the world knowing about the violence occurring in Algeria, the journalists changed the text accompanying the image and stated that the woman was a mother mourning the death of her eight children. The real story behind the photograph is that the woman was mourning over three of her relatives; changing the narrative behind the image inevitably gave it more power visually as McGonagle has said here: “positioning her as a mother mourning the loss of her eight children allowed commentators to draw parallels with notions of motherhood worldwide.” (McGonagle 2014: 80) Of course, any family member dying is devastating for a person, but society tend to feel more empathy towards a supposed mother and her incomparable grief over her own children in the centre of war.

Religious iconography is another factor that the media include in images of conflict, this is something that I feel can be a positive attribute. Such as with Samuel Aranda’s image (Figure 11), the photograph depicts a mother cradling her adult son after she found him to be alive during the devastating chain of events; the picture has been linked to Michelangelo’s Pieta. (Figure 12) In comparison to Michelangelo’s Pieta, advertising company Benetton released a controversial campaign in 1991 of the same name, exposing the reality of AIDS. (Figure 13) The photo depicted AIDS activist David Kirby as he laid on his deathbed in hospital, surrounded by his family. The original photograph was taken by Therese Frare (Figure 14) and Benetton’s art director Oliviero Toscani enlisted artist Ann Rhoney to colourise the image with oil paint to give it more shock value.

Although the campaign was received both negatively and positively for its Christian comparisons to Pieta, I feel that it is an authentic representation of human suffering, much like Aranda’s Yemen work because we know it has happened and is still happening globally today. Benetton’s advert and Aranda’s image, I feel, are successful examples of when Christian iconography is used properly. In relation to my view, Toscani has commented that “The Michelangelo’s Pieta during the Renaissance might be fake, Jesus Christ may never have existed. But we know this death happened. This is the real thing.” (Toscani 1991) Relating images of conflict and suffering to a biblical narrative such as Mary and Jesus, is an exceptional way of attracting the viewer’s attention. Audience’s usually feel more empathy towards imagery of a family circle in my opinion, their compassion becomes heightened due to them thinking about their own families and how they would feel personally in the same situation. As Coomes says here of Aranda’s image and I believe that it can also be connected to Benetton’s advert, “the Renaissance style of lighting elevates it from an illustrative news picture to something that has a heritage.” (Coomes 2012)

Balog argues, “I’ve tended to look for an engaging way, not always a beautiful way, to pull people into the subject and make them care about it. And then, at the same time…(to) deliver a message behind that beautiful picture that says, ‘Things aren’t what you wish they were; things aren’t what they could be.” (Balog 2013: 132) This comment I feel, can be connected to how people reacted when the Abu Ghraib images were released; they again present religious tendencies, but in their case at a much darker level. In particular, the image that circulated at a faster rate than any other from Abu Ghraib was that of The Hooded Man. (Figure 1) The way in which the man’s arms are outstretched like Jesus’s were during his crucifixion (Figure 15), his hands being attached to electrical wires, much like Jesus’s hands were pinned in with nails to the cross – the image mimics the brutality that Jesus endured before his death.

The Hooded Man was also chosen for many international and global newspapers/magazines covers (Figure 16), most likely because I feel journalists knew it would attract immediate attention due to its raw and intense visuals; additionally that religious symmetry favours the eyes of most.“These forms of savagery are neither mere images nor mere actions, but are designed to be both: they are propaganda of the spectacle and of the deed.” (Linfield 2010: 152) As Linfield says here, these types of images are not there to beautify conflict but to create a reaction among people and educate them on how humans can become the overall enemy of humanity itself. The Abu Ghraib images were not released to be easy to view or to understand the actions of the American military. They were shown to expose the brutal truth of conflict behind closed doors; not everything we read about is proof of its subject and the issue certainly attracted the media’s attention (Figure 17). As Cartier-Bresson says here: “Life isn’t made of stories that you cut into slices like an apple pie. There’s no standard way of approaching a story. We have to evoke a situation, a truth.” (Cartier Bresson 2013: 36)

In addition, images such as the ones that came from Abu Ghraib should be the types of images we all collectively see when it concerns the topic of conflict; we need to see the chaos of a situation to understand its origin so that eventually, conflicts are reduced gradually. Without these types of photographs, the narrative cannot and in my opinion should not be released into the world. “As a journalist, I’m obliged to concede that the broadcasting of the images was a succinct demonstration of the visceral power of photos over the written word.” (Worthington 2009) Overall, I feel that shock tactics used in a conflict image are always the worthier choice; the subject of conflict should not be approached with caution, especially when vital visual information is at stake of being disregarded. Although talking about Abu Ghraib, I feel that this comment can be applied to photographs of a similar nature and represents how I feel about shocking images of conflict: “These photographs expose the essential blindness that constitutes the act of seeing as such.” (Phelan 2012: 55)

Chapter 2: Tackling Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue and pleasing aesthetics create a vicious circle and, in some way, marry up to one another surprisingly. Without beautiful aesthetics, society becomes immune to the empathy they should be feeling when divulging conflict of war images; and when contradictive beauty takes its place within a photograph, people tend to only focus on that factor and not the narrative behind the colours. Whether or not this complication will ever be fixed is a question I cannot answer, but what I am certain of is that photographers should be focusing on what Ritchin says here – we must “incite discussion and attract attention.” (Ritchin 2013: 39)

A strategy that I believe combats compassion fatigue is that of citizen journalism; this type of imagery is raw and attracts the attention of people that abstract journalism cannot.For example, the assassination of Pakistan’s former prime minister Benazir Bhutto that was captured by photojournalist John Moore at the very moment it occurred. The images (Figures 18 & 19) are visually catastrophic in keeping with the tone of the event; although they are not necessarily clear to understand, the physical facial expressions of surrounding people and the blurriness of the scene are enough to comprehend how disastrous it would have been to be there. Moore is not a citizen journalist per say, but his illustration of the attack was unplanned and is not the initial reason that he was there in the first place. He was at that time, a citizen voluntarily photographing the event – images that would later be a representation of the brutality endured by the involved people. The reason that I feel Moore’s pictures can be related to that of citizen journalism, is that they are closely similar to the images taken at the scene of the 7/7 bombings in London. (Figure 20)

These types of images may not be perfectly constructed to fit the editorial choices of magazines and newspapers, but they are an honest outline of how events of conflict can happen without warning – we must continue to deliver these photographs to inform people within the area. We can relate more efficiently to citizen journalists and I support my argument with this statement from Ritchin: “Many viewers may empathize with the motivations of these ordinary citizens, which are possibly similar to their own.” (Ritchin 2013: 11)

In comparison, artists Broomberg and Chanarin have said in an interview discussing photojournalism and conceptual photography, that Moore’s image from Pakistan was the catalyst for them to create their project The Day Nobody Died. Their intention for this project was to “create in the mind of the viewer, a question. Which was; what do you expect to see, what do you want to see and how much would be enough evidence for you.” (Chanarin 2012) Broomberg and Chanarin wanted to question whether images of conflict should be as brash and visually raw as the images that come mostly from citizen journalism. They took a roll of film out to Afghanistan and each time a conflicting event would happen; they would expose the film for 20 seconds into the light. (Figure 21)

This piece of work in my opinion, is not a valid alternative to citizen journalism and does not contain any valuable information at all regarding a scene of conflict. I agree with O’Hagan with his opinion on the project that, “they are in a warzone and their decking about with some conceptual joke, I think it’s patronising and arrogant.” (O’Hagan 2012) However, I do agree with Broomberg when he argues that, “why in 2012, are we seeing images that are less analytical and critical than they were in 1960. Something’s gone wrong, we are being controlled, there’s a clear act of censorship going on.” (Broomberg 2012) Consistently, we are bombarded with images of conflict that are not representative of the narrative that has occurred and this I feel, is the reason for society’s demise in feeling any form of compassion towards the subject of visual warzones.

Chapter 3: The Rwandan Genocide: Did Western Media Fail?

The overstuffed nations watched CNN and shook their heads in silence.” (Gannett News Service 1999: 283) In my view, the Rwandan Genocide of 1994 should have been an event that was publicised worldwide from start to finish; however, the Western media in their typical ‘late to the party’ fashion decided against releasing the images – that was until the death toll had soared to an unsustainable amount of 900,000 and help seemed to disappear into the abyss.“Only when the genocide turned into a refugee crisis, did either the public or government take any aggressive action.” (Moeller 1999: 284) As Moeller argues here, up until this point, nobody across the globe had an insight into what was happening in Rwanda. Yet the first images they were introduced to were of refugees fleeing the country (Figure 22) and not the cause of this action. It would not be for another four months that an international audience would be made privy to the true reason for the civilian escape. (Figure 23)

Only a select few of photographers such as Alfredo Jaar and Gilles Peress (Figure 24), succeeded in producing the right work that was representative of the horror during the Rwandan Genocide. Other photographers such as (Figure 25), simply masqueraded any importance from the genocide by providing the public with superficial journalism. Yet, these were the types of images that were chosen to be published first because the feelings of society were considered before the feelings of the victims. As Davies has argued here, “these are journalists who are no longer out gathering news but who are reduced instead to passive processors of whatever material comes their way, churning out stories, whether real event or PR artifice, important or trivial, true or false.” (Davies 2010: 46) It took a considerable amount of imagery to be released before any hierarchal figure decided to take action and offer their services of aid, as Polman explains here, “Africans especially have to kick up a considerable fuss to be heard and seen by donors, since modern history sets a high threshold for attention to ‘yet another African war drama.’” (Polman 2010: 161)

In my opinion, the media had failed, as Moeller states here quoting from the 1996 report The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwandan Experience, “The Western media’s failure to report adequately on the genocide in Rwanda possibly contributed to international indifference and inaction, and hence the crime itself.” (Moeller 1999: 298) Ritchin argues that “one of the most contested and restricted purviews of professional photographers has been the coverage of war.” (Ritchin 2013: 16) During thier time in Rwanda, photographers Giles Peress and Alfredo Jaar (Figure 26) managed to achieve what I believe to be almost impossible amongst photojournalism nowadays. I argue that they successfully produced images that represented what Western society should have been exposed to from the beginning; where beauty was not the favoured inclusion in the photographs and people could finally see the horrors that had occurred among Rwanda through their use of shock tactics. Although, it was not an easy task to follow through on because “imagery of a larger societal significance has a much harder time surfacing, let alone demanding attention.” (Ritchin 2013: 9) I agree with Ritchin here, as we know that with Jarecke’s Incinerated Soldier (Figure 6), that all American magazines/newspapers refused to publish the image due to its shocking graphics.

Jaar approached the genocide of Rwanda through the eyes of the survivors and it has been noted that “The Rwanda Project can be regarded as a form of epos, an epic poem dedicated to the Rwandan Genocide.” (Gervat 2014) The Rwanda Project is extremely intense in my view and includes repetition of certain images of his, but I feel that this appearance is vital in truly representing the tone of the subject; how powerful figures worldwide were repeatedly shown images from the genocide and simply did nothing. It is displayed in various forms and follows an aesthetic style to explain how the world failed to respond to the genocide.

For example, a section entitled Eyes of Gutete Emerita (Figure 27) shows the eyes of a surviving mother; the text accompanying this image explains how Gutete was attending Sunday mass at her local church when the slaughters of 400 Tutsi men, women and children began right before her eyes; among those were also her husband and two sons. At times, the entirety of an image is not needed to fuel emotive narrative, and this is an example of how it can be achieved. Gutete’s eyes are harrowing to stare at, to imagine what she must have seen – the same images that Western society would have been shown during the massacre, yet they failed and still fail today to feel compassion towards distressing conflict images in the media. “What had happened during the coverage of the genocide was in hindsight less compassion fatigue, and more compassion avoidance.” (Moeller 1999: 306)

Personally, I cannot understand why aesthetically beautiful images are more successful in the public eye, especially if it is concerning terror among cultures. The people of Rwanda experienced an event that is incomprehensible to the human mind; it was a menacing attack of massacre – massacre is not picturesque, so why should the photographer’s images appear this way? Indeed, Jaar also exhibited the Rwanda Project in a way that exudes power upon any person that viewed it; Figure 28 shows a secondary way that the Eyes of Gutete Emerita were exhibited

Jaar exhibited Gutete’s eyes on a huge light box, consisting of one million slides along with magnifiers for visitors to use to investigate the images closer. In my opinion, this allowed the audience to inspect closely the haunting stare and focus of Gutete’s eyes onto theirs, reiterating that her eyes, are eyes of sorrow from a deadly massacre. The proportional amount of slides connects with the final count of corpses from the Rwandan Genocide; the way in which the slides pile above people walking around the table extenuates I feel, both the presentation of how the bodies were piled on top one another without care throughout the killings, and the amount of onlookers during the carnage. Western onlookers who watched and waited for it to end so that their services would not be needed, regardless of the amount of graphic imagery they were shown through the media. Gervat has argued about the various ways in which Jaar exhibited his work, that “they are all poetic exercises in representation that are at once a dirge and exaltation, an effigy and an elegy, a promulgation and a denunciation of the Rwandan Genocide and the world’s failure to respond to it.” (Gervat 2014) I agree with Gervat here, Jaar is demonstrating to the public through presentation, the amount of fatalities and the experiences of survivors whose voices were ignored among the rubble of superficial journalism, courtesy of the Western media.

However, Jaar was sceptical about how he had produced work from the Rwanda Project commenting, “I feel that it wouldn’t make any difference to show these images because I feel people here have lost the capacity to see, they have lost their capacity to be affected.” (Jaar 2004: 62) But I disagree with Jaar here, he is proving how powerful cropped images can be, not always having to be explicitly graphic, but nevertheless pinning the audience in the same way. I do agree with Jaar however, that people – meaning the Western world – have lost their compassion to feel something when looking at an image of conflict or post conflict.

Williamson (1994) however, took a different direction when it came to publishing photographs from the genocide. In my opinion, the style in which Williamson chose was that of how photojournalism should be executed for news information purposes. Williamson arrived six days after the Rwandan president was assassinated, instantly hearing the cries of victims who were being hacked to death when he stood upon the bridge at night. Williamson’s image (Figure 29) of bodies floating in the Kigali river is shocking due to its graphic nature and shows no attempt to hide the true subject matter of murder. Yet, even with images such as this one where you can see bloodied, decomposing bodies floating in the remnants of other corpses, both the public and officials across the Western front did not intervene to offer help. “Our failure is one of imagination, of empathy.” (Sontag 2004: 7) I argue that Sontag’s comment relates to how Western society is continually falling into the deep depths of compassion fatigue; fuelled by the ignorance that it is simply not their business to interfere in another ‘helpless conflict’, regardless of the floods of horrific images that come from it. In addition, I feel that this fatigue is not helped when we as a community are informed first with images (Figures 22 & 25) that can only be labelled as superficial.

In comparison, I would argue that the majority of Williamson’s images were lacking the accessories that are vital in an image to evoke a sense of ‘stand up and act’ in people. Such as, this image here of a child in Rwanda suffering from a cold. (Figure 30) This photograph has clearly been constructed for beauty purposes only; when a genocide is raging within the walls around this image, these are not the visuals we should be seeing instead. On the poor construction of images, Baudrillard argues that “rather than creating communication, it exhausts itself in the act of staging communication. Rather than producing meaning, it exhausts itself in the staging of meaning.” (Baudrillard 1994: 80) Although the media is aware that an audience responds well to the face of another African child in the midst of conflict, this image is not representative of the true context behind it. This photograph in particular, should not have been printed to be a representation of the Rwandan Genocide; caption or no caption, it still does not show the massacre that was happening, resulting in deaths that were accumulating “at nearly three times the rate of Jewish dead during the Holocaust.” (Gourevitch 1999: 280)

On the other hand, Jaar’s work from the Rwanda Project is more illustrative of the Rwandan Genocide and the controversies behind it especially. I feel that Jaar was extremely clever in showing just how neglected the genocide was when it came to being included in the worldwide press. He exhibited this piece (Figure 31) entitled Newsweek, in which he exposed how it took a renowned American magazine like Newsweek, sixteen weeks before their front page was covered with the horrors of Rwanda. Yet, that the journalists of Newsweek were most definitely aware of the genocide; yet they simply ignored the conflict because they were ordered to do so by American security officials. Instead, they were told to fill their front covers with more ‘culturally appropriate’ stories for the people of America. When Rwanda’s time finally came to be in the spotlight, it was August 1st 1994, four months after the genocide had begun and an estimated 900,000 Rwandans had been slaughtered alone, as well as another 2 million people who had fled, eventually dying from cholera.

In my opinion, what Jaar has shown here, is that anything that is covering our newspapers or magazine front pages, could be completely irrelevant compared to more important events happening that we are unaware of; the mass media “are the vehicles for the simulation internal to the system and the simulation that destroys the system: (Baudrillard 1994: 84) Additionally to this point, “as a result of the risks and costs, ‘a lot of the coverage has been superficial.’” (Jennings 1999: 293) Or in this case, non-existent for sixteen weeks while women, men and children were killed on their own territory for simply not having the right identification card.

Conclusion

Conclusively, I argue that without the use of shock tactics within conflict photographs, we can never truly understand the storyline of the event. These types of events are not meant to be reconstructed for our viewing pleasure, they are available to us in order to show the realism of everyday conflicts and the inhuman actions that take place. As Taylor has commented here: “What would it mean for knowledge if the images ceased to circulate, or were never seen in the first place? What would it mean for civility if representations of war crimes were always polite? If prurience is ugly, what then is discretion in the face of barbarism?” (Taylor 2014: 85)

If photojournalists can use their valuable access to warzones for the benefit of illustrating the authentic story to citizens around the world, this could result in us seeing illustrations that we do not see often, due to the control of censorship from hierarchal officials. Journalists must push against these ridiculous expectations from powerful figures; figures who are not in the centre of the conflict and in turn have no authority to dictate what should or should not be shown in the media.

Superficial journalism is unfortunately becoming more apparent presently in the media; this downward spiral of dishonesty must be dealt with before we no longer have an urge to witness any form of media, due to continually questioning what is and is not a true representation of conflict.

References

- BALOG, James. 2013. (As cited in RITCHIN, Fred. 2013. ‘Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary and the Citizen.’) Aperture Publishing

- BARTHES, Roland. 1977. ‘Image, Music, Text’. London, United Kingdom: Fontana Press, Harper Collins Publishers

- BAUDRILLARD, Jean. 1994. ‘Simulacra and Simulation’. Michigan, United States of American: University of Michigan Press

- BROOMBERG, Adam. 2012. ‘What is Conceptual Photography?’. Youtube Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9TvpxG9fLqo (Accessed 15/11/2019)

- BURNS, Ken. 1991. ‘The Painful, Essential Images of War’. The New York Times Online. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1991/01/27/arts/the-painfulessential-images-of-war.html (Accessed 12/11/2019)

- CARTIER-BRESSON, Henri. 2013. (As cited in RITCHIN, Fred. 2013. ‘Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary and the Citizen.’) Aperture Publishing

- CHANARIN, Oliver. 2012. ‘What is Conceptual Photography?’. Youtube Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9TvpxG9fLqo (Accessed 15/11/2019)

- COOMES, Phil. 2012. ‘The story behind the World Press Photo’. BBC News Online. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/17111673 (Accessed 11/10/2019)

- DAVIES, Nick. 2010. (As cited in POLMAN, Linda. 2010. ‘The Crisis Caravan: What’s Wrong with Humanitarian Aid?’). New York, United States of America: Henry Holt and Company Publishing

- FRIEDERSDORF, Conor. 2014. ‘The War Photo No One Would Publish’. The Atlantic Online. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/08/the-war-photo-noone-would-publish/375762/ (Accessed 6/11/2019)

- GANNETT NEWS SERVICE. 1999. (As cited in MOELLER, Susan D. 1999. ‘Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death’). Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Publishing

- GERVAT, Briana. 2014. ‘The Penetrating Epic Poem: A Conversation with Alfredo Jaar’. Art Pulse Magazine Online. Available at: http://artpulsemagazine.com/thepenetrating-epic-poem-a-conversation-with-alfredo-jaar (Accessed 10/10/2019)

- GOUREVITCH, Philip. 1999. (As cited in MOELLER, Susan D. 1999. ‘Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death’. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Publishing

- JAAR, Alfredo. 2004. (As cited in RITCHIN, Fred. 2013. ‘Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary and the Citizen.’) Aperture Publishing

- JARECKE, Kenneth. 2014. ‘The War Photo No One Would Publish’. The Atlantic Online. Available at:https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/08/the-war-photo-noone-would-publish/375762/ (Accessed 6/11/2019)

- JENNINGS, Peter. 1999. (As cited in MOELLER, Susan D. 1999. ‘Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death’. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Publishing

- LINFIELD, Susie. 2010. ‘The Cruel Radiance’. Chicago, United States of America: University of Chicago Press

- MCGONAGLE, Joseph. 2014. (As cited in KENNEDY, Liam and PATRICK, Caitlin. 2014. The Violence of the Image: Photography and International Conflict.’) London, United Kingdom: I.B. Tauris Bloomsbury Publishing

- MOELLER, Susan D. 1999. ‘Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death’. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Publishing

- O’HAGAN, Sean. 2012. ‘What is Conceptual Photography?’. Youtube Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9TvpxG9fLqo (Accessed 15/11/2019)

- PHELAN, Peggy. 2012. ‘Picturing Atrocity: Photography in Crisis’. London, United Kingdom: Reaktion Books Ltd

- POLMAN, Linda. 2010. ‘The Crisis Caravan: What’s Wrong with Humanitarian Aid?’. New York, United States of America: Henry Holt and Company Publishing

- RIEFF, David. 2013. (As cited in RITCHIN, Fred. 2013. ‘Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary and the Citizen.’) Aperture Publishing

- RITCHIN, Fred. 2013. ‘Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary and the Citizen.’ Aperture Publishing

- SMAIDMENT, Unknown. 2015. ‘Richard Mosse: The Enclave’. National Gallery of Victoria Online. Available at: https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/richard-mosse-theenclave/ (Accessed 13/11/2019)

- SONTAG, Susan. 2004. ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books Publishing

- SONTAG, Susan. 2004. ‘Regarding The Torture Of Others’. The New York Times Online. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/23/magazine/regardingthe-torture-of-others.html (Accessed 12/11/2019)

- TAYLOR, John. 2014. (As cited in KENNEDY, Liam and PATRICK, Caitlin. 2014. ‘The Violence of the Image: Photography and International Conflict.’) London, United Kingdom: I.B. Tauris Bloomsbury Publishing

- TOSCANI, Oliviero. 1991. (As cited in MACLEOD, Duncan. 2007. ‘Benetton Pieta in AIDS Campaign’.) The Inspiration Room. Available at: http://theinspirationroom.com/daily/2007/benetton-pieta-in-aids-campaign/ (Accessed 13/11/2019)

- WORTHINGTON, Andy. 2009. ‘Images that exposed the truth on abuse’. The Guardian Online. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/apr/28/abu-ghraib-prisonerabuse-us (Accessed 11/10/2019)

Bibliography

- BRENT PLATE, S. 2008. ‘Religion and Film: Cinema and the Re-creation of the World’. London, United Kingdom: Wallflower Press

- CATON-JONES, Michael. 2005. ‘Shooting Dogs’. (video: DVD)

- ELKINS, James. 2001. ‘Pictures & Tears’. New York, United States of America: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group

- GEORGE, Terry. 2004. ‘Hotel Rwanda’. (video: DVD)

- GOUREVITCH, Philip. 2019. ‘The Silence: 25 Years Since the Rwandan Genocide’. Magnum Photos Online. Available at: https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/conflict/gilles-peress-silence-25years-since-rwandan-genocide/

- KAPHLE, Anup. 2014. ’11 powerful photos from the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide’. The Washington Post Online. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2014/04/02/11-powerfulphotos-from-the-aftermath-of-the-rwandan-genocide/

- KINGSLEY, Patrick. 2016. ‘The death of Alan Kurdi: one year on, compassion towards refugees fades’. The Guardian Online. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/sep/01/alan-kurdi-death-one-year-oncompassion-towards-refugees-fades (Accessed 16/11/2019)

- LYONS, Robert & STRAUS, Scott. 2006. ‘Intimate Enemy: Images and Voices of the Rwandan Genocide’. Brooklyn, United States of America: Zone Books

- MARSHALL BEIER, J. 2011. ‘The Militarization of Childhood: Thinking Beyond the Global South’. New York, United States of America: Palgrave Macmillan, St. Martin’s Press

- NACHTWEY, James. 2011. ‘When the World Turned Its Back: James Nachtwey’s Reflections on the Rwandan Genocide’. Time Magazine Online. Available at: https://time.com/3449593/when-the-world-turned-its-back-james-nachtweysreflections-on-the-rwandan-genocide/ (Accessed 16/11/2019)

- O’HAGAN, Sean. 2011. ‘Turning photojournalism upside down’. The Guardian Online. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/apr/19/broombergchanarin-photojournalism-war (Accessed 16/11/2019)

- PERESS, Gilles. 1995. ‘The Silence’. New York, United States of America: Scalo Publishers

- PHILLIPS, Sarah. 2012. ‘Samuel Aranda’s best photograph: a woman protects her son’. The Guardian Online. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/nov/07/samuel-aranda-bestphotograph

- PROSSER, Jay. 2012. ‘Picturing Atrocity: Photography in Crisis’. London, United Kingdom: Reaktion Books Ltd

- SAID, Edward W. 1991. ‘Orientalism’. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books Publishing

- TAFT, Sally. 2014. ‘How did you help us change the way we report the news?’. BBC News Online. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-30421631 (Accessed 16/11/2019)

- UNKNOWN. 2011. ‘Gulf war, 20 years on: memories of Desert Storm’. The Guardian Online. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jan/16/gulf-war-20years-on (Accessed 16/11/2019)

- VERGER, Rob. 2014. ‘Newsweek Rewind: The Genocide in Rwanda’. Newsweek Online. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/newsweek-rewind-genociderwanda-245635 (Accessed 16/11/2019)