New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape at The George Eastman House (1975)

Visual Detachment & Political views?

By Amy Miles (16th Decemeber 2019)

‘Their stark, beautifully printed images of this mundane but oddly fascinating topography was both a reflection of the increasingly suburbanised world around them, and a reaction to the tyranny of idealised landscape photography that elevated the natural and the elemental’ (O’Hagan, 2010)

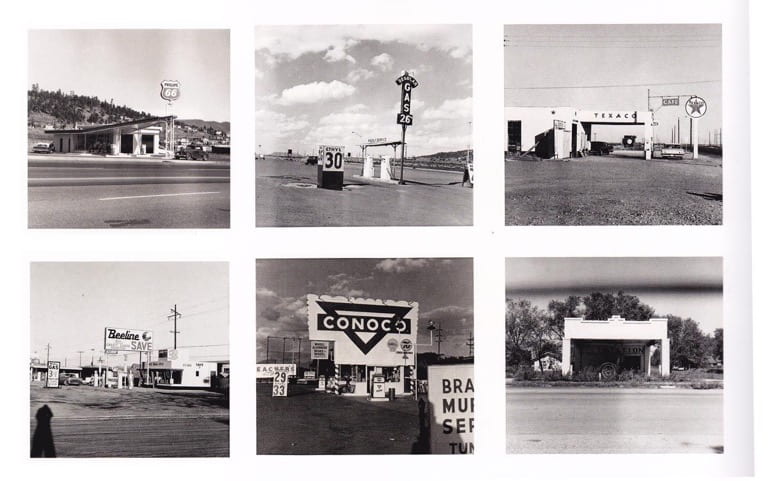

The International Museum of Photography New Topographics (1975) was pivotal in the development of American landscape photography. Gone were the romantic, sublime visions of an unspoilt American frontier. Rather, the artists included in the show (Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd & Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel) projected a version of America full of tract houses and industrial estates, a more anthropological, objective view of human imprint on the American land.

‘Looking at the work, what comes to the fore is the predominant spirit of the solitary road trip as a working model. The photographs evoke Evans’ American Photographs (1938) and Frank’s The Americans (1958) as much as Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) and the Dennis Hopper-directed Easy Rider (1969)’ Many of the series were products of cross-country journeys, and all showed the conflict between the frontier spirit of traversing the majestic countryside and the stark reality of the pale, dank sprawl of motels, shops and houses that they encountered (Lange, 2010)

this session could be run in conjunction with:

- Postcards from Home

- A Walk on the Wild Side

- A Sublime Sight – post to come

- What is a Photograph at the ICP (2014)

Traditionally, the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of landscape photography, might be something similar to the work of Ansel Adams – a romantized and idealic view of the American land. However these photographers didn’t follow in these footsteps at all, and started to capture what our landscapes really looked like. The curator of New Topographics, William Jenkins, aimed to show an America from a more neutral and non-biased stance, removing the photographers specific emotions or styles. Whether or not this accurately described the artists’ intentions, in retrospect we certainly have a more politically aware view of this ‘man-altered landscape’ (Rosa, 2010). Heavily influenced by the work of Ed Ruscha (strangely not included in the show) Jenkins muses;

‘the pictures were stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion … [this was[ rigorous purity, deadpan humor and a casual disregard for the importance of the images’ (Jenkins in Hershberger, 2013, p.236)

Aims & Outcomes:

- For participants to consider a history of American landscape photography and a shift to a more political approach. How are photographers influenced? Is thiss political approach inherent today? Has there been a polarisation in the way we visualise the land between vernacular and gallery contexts?

- For participants to take a critically informed personal stance to evaluate exhibitions / works and the curatorial rationale and intent.

- To reflect on the nature of the gallery context and questions of taste, value and judgement. Is it ‘good’?

- Participant Outcome: To critically evaluate an exhibition of thier choice, considering curatorial intent, selection of works, and reviews. Would thier own practice fit into this and why? *Participants could also be encouraged to ‘curate’ thier own exhibition / include thier own work in this and consider the curatorial rationale.

Walker Evans was also a clear influence for this new generation of photographers. His work refused to romanticise poverty, to create perhaps a more realistic (but certainly more objective) view of the American Depression.

However, Evans images have been debated (e.g. Whitman, 1975, Tagg, 2003, Tedford, 2017) upon whether they were taken from a detached point of view, or whether he was sgiving his subjects dignity (if not sympathy). Frank Gohike emphasises Evans influence on his practice, most importantly, the detached viewpoint, that ‘The attempt to make a photograph from which the photographer seems to be absent is a strategy whose value and power all of us I think primarily learned from [Evans]’ (Gohlke in Salvesen, 1975, p.17).

presentation: New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape (George Eastman House, 1975)

Robert Adams work is evidently based on this subjective relationship between man and the landscape. His work could be interpreted in a way that shows his emotional opinions towards how the landscape has changed and affected the environment.

For example, Dennis (2005) critiqued this image as: ‘The tree in the foreground is not only dwarfed by the enormous sprawl of the city behind it, but also acts as a lone and pathetic reminder of what has been displaced by urban development.’ That said, there is still evidence of an emotional / visual detachment in the outcome. It is not implausible to suggest that the image posits an subjective position towards the ongoing march of man.

One might argue that the work of Lewis Baltz were taken from a similarly detached and clinical viewpoint, but yet that that the ongoing march of human development around him made he, himself, feel detached – expressed also visually (and subjectively).

Gosney (2013) posits this view, that ‘Lewis Baltz’s stark images juxtaposed the contrary ugliness inherant in industrial tracts and national parks…symbolising what many saw as problems of the modern age’ (Gosney, 2013). However, it must also be noted that Baltz’s images are paradoxically akin to social research.

New Topograhics exhibition in 1975 was not just the moment when the apparently banal became accepted as a legitimate photographic subject, but when a certain strand of theoretically driven photography began to permeate the wider contemporary art world. Looking back, one can see how these images of the “man-altered landscape” carried a political message and reflected, unconsciously or otherwise, the growing unease about how the natural landscape was being eroded by industrial development and the spread of cities’ (O’Hagan, 2010)

Suggested Session Outline:

- Ask participants to conduct in depth research into the work of at least 2 of the practitoners included in the New Topographics exhibition

- Do they have any similar reference points / visual or conceptual infuences? What are the commonalities? What are the differences? Why do you think William Jenkins curated them in the same show?

- If you were the curator: Of the practitoners included in the show, which work would remain? And which would be rejected?

- If you were the curator: How you adapt the show today? Are there any new works you would include? By whom and why?

- Would you include your own photographic practice? Could you make work in this detatched yet politically present way? Of what, and why?