Dinu Li

Dinu Li is a multi-disciplinary artist and Senior Lecturer at Falmouth University who has exhibited internationally for both solo and collaborative shows. His practice delves into his engagement with his Chinese heritage, the socio-political conditions of place, as well as the intangibility of memory. This interview is a dissemination of a number of key areas ranging from his migration to the U.K and his discovery of photography, through his projects as a professional and his insight into the current educational climate.

by Louis Stopforth (4th june 2021)

LS: You mention your first encounter with photography and how you could read the images. Is this something you have found with producing works of your own, that you could communicate beyond language barriers?

DL: I have been surrounded by photographs since my childhood, growing up in Hong Kong. My dad came to the UK when I was a few months old, and so my understanding of him came via photographs of him displayed on my mother’s dressing table. There were images of him posing in Trafalgar Square, or standing in a snow filled park, or standing next to his car. Those snapshots were placed next to photographs taken in China of my aunt, uncle and cousins. As the photographs were quite small, I paid a lot of attention to observing all the details contained within the compositions, creating my own narratives around what I saw.

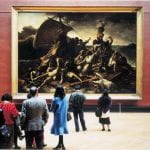

I then came across the photographers Chris Killip and Joseph Koudelka by accident whilst wandering around a bookshop in my early-twenties. Up until then, I hadn’t taken photography seriously. I walked randomly inside the store, and casually arrived into the arts department, stopping at bookshelf ‘K’. Without thinking, I pulled out two books, In Flagrante by Killip and Exiles by Koudelka. Using my intuition, I was able to dissect the images to make sense of the world as seen through the eyes of both photographers. I guess my formative years looking at my family photographs must have helped, as I seem to have been able to read those images as if reading text.

LS: Your work delves between contrasts of barriers as well as unity within humankind. Has emigrating as a child caused these themes to have significant prevalence in you work? Especially as you navigated through various cultures and sub-cultures as you settled in England?

DL: Working class families in Hong Kong live in densely populated environments, and neighbours can appear as if they are literally living besides you. As we didn’t have a television at home, I spent my childhood peering through the cracks and gaps of closed shutters or venetian blinds, so I could watch tv programmes from other people’s televisions. My understanding of popular culture was one of half experiences or half satisfactions, as I never got the full picture from looking through those gaps.

I was brought up in Hong Kong when it was still part of the British colony, and so the sounds coming from my neighbour’s television sets was a melting pot between Chinese opera and American detective series depending which channel those families were watching. At one time, I recall going to the cinema twice in one week, watching Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs one day and Chinese revolutionary ballet on another day

I moved to the UK as a seven-year old, but settling here was not easy, as the locals were unwelcoming to foreigners. Within weeks of my arrival, two boys living a few doors away pounced on me one day, as I was about to set off for school. They pushed me against a wall, slapped me around a few times, and filled my pants with handfuls of soil. As they ran off, they shouted “get back to where you come from”. As disturbing as it was, that memory has been a catalyst to some of my work in my art practice. It has been a paradoxical concept to imagine a backwards walk to one’s birthplace, with a trail of British earth leading from a point of departure to a final point of destination.

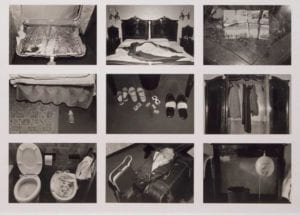

LS: We Write Our Own History is a photographic body of work that consists of arrangements constructed by demonstrators from the 2014 Hong Kong protests, displaying incidents they experienced. When looking at this work classical painting, particularly works from the Dutch Golden Age, come to mind as unassuming objects carry metaphorical significance. Did you ever think of the work in this way when it was produced?

DL: I have a deep appreciation of painting from the Dutch Golden Age, and it is ironic how my images from We Write Our Own History shares similar tensions to one particular painter of that period called Clara Peeters. For example, it is noticeable in so many of Peeters’ paintings that her table top items are often placed on the very edge of the table, as if on the verge of tipping over. This causes a sense of unease that I hope is also apparent in my photographs.

Another striking feature is the incongruous manner by which items are placed, as if going against traditions of still-life painting. In her painting Still Life with Flowers, Goblet, Dried Fruit and Pretzels (1611), Peeters places a large goblet not only at a central vantage point, but also in front of much smaller items. This is unusual, as such items had historically been placed at the back of a large arrangement, to avoid blocking an overview.

LS: When studying under you, you encouraged collaboration with others. Does this advice stem from your own experience engaging with art institutions or projects in which you have made investigations in conjunction with people? Or is there another reason you stress the importance of collaboration and partnerships?

DL: The status of art and artists was put in question by Duchamp, who acted as agent provocateur, provoking deeper critical engagement in the arts, and as a challenge to systems, institutions and traditions. I share Duchamp’s sentiments in challenging the status quo, and wish to be considered a verb, rather than be labelled by a noun.

By verb over a noun, I mean it is not important for me to be classified as an artist. It is only important to me that I have actioned something or made something. When my work is good, it maybe classed as art or otherwise. Since post-modernity, the status of art has been questioned further, and so the emergence of sharing that status by participation, collaboration and community engagement was inevitable.

The post-modernist American architect Buckminster Fuller wrote the book I Seem to be a Verb (1970), in which he states “I live on Earth at the present, and I don’t know what I am. I know that I am not a category. I am not a thing – a noun. I seem to be a verb, an evolutionary process – an integral function of the universe.” By that account, and being an integral function, it is no accident that I seek to share the production or delivery of art making with others. At times, my function is simply as facilitator.

LS: Memory and narrative are consistent themes within your works, in particular your trilogy of films within The Anatomy of Place, and your project The Mother of All Journeys. Why is this? Is it an engagement with your native culture or is it a way of providing physicality to an otherwise intangible that may otherwise one day become forgotten?

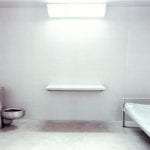

DL: Yes, I think you’ve guessed correctly. Perhaps the best way to answer your question is to elaborate on another artist, the sculptor Rachel Whiteread. Her sculptures take the form of resin casts, allowing Whiteread to give space a physical presence. What we bypass and ignore everyday are our spaces, as space is invisible. But by giving space a substance, not only does it become visible, but they occupy more presence, more prominence. One of my favourite pieces by Whiteread is also one of her earliest works called Shallow Breath (1988) in which she casted the intimate space directly underneath her father’s mattress, as if Whiteread is making visible, the invisible breaths by her father, breaths that could have infiltrated into the underside of his own bed.

LS: In regards to your trilogy of films (Ancestral Nation, Family Village and Nation Family) was it due to having extensive time working on an off with one subject that the work was concluded as a trilogy or was it more than this?

DL:The genesis to my trilogy came about because I was interested in the word ‘country’ in its Chinese written form. In Chinese, that word can be expressed in three different ways, partly depending on the evolution of the Chinese lexicon, partly due to personal circumstance and so on. For example, in ancient China ‘Ancestral Nation’ would have been used to express the word for ‘country’. People who leave China to emigrate to far away countries often use the words “Family Village” due to its nostalgic undertone. However, Nation Family is the most common way to express the word for ‘country’.

Nation Family Trailer from Dinu Li on Vimeo.

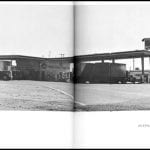

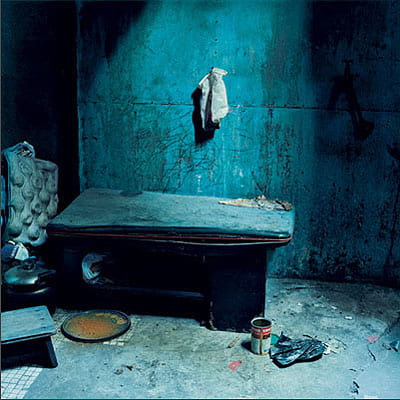

I simply used those three terms as titles for each of my trilogies, and made work in response to the words. For example, for Ancestral Nation, some of the work took place in Qufu, the birthplace of Confucius, the philosopher generally understood to have helped shape the Chinese characteristics. For Family Village, I examined vernacular architecture in contemporary China. And for Nation Family, I interrogated a specific period in the life of a cousin, by using an old black and white photograph of him as my starting point. It is one of the photographs I looked at as a child growing up in Hong Kong.

LS: During The Mother of All Journeys there is an emphasis on memory, and its relationship to actual time and space. Was the use of photography for you essential given its almost institutionalised place as an artefact of record and its own connection to time and space?

DL: In that project, I was interested in interrogating the authenticity of memory itself and to also problematise photography as a form of documentation. I guess the work started all the way back to those years when I used to form my own narrative about family members through their photographs displayed on my mother’s dressing table. In those years, my mother told my stories related to each photograph, which mixed in with my own imagination about the lives of my relatives. The Mother of All Journeys was an attempt to piece together a jigsaw puzzle of my mother’s life experiences, using old family snapshots to aid our journeys.

By the time I was ready to make this work, my mother was already in her 70’s and being forgetful about memories she has instilled in me. Our collaboration involved me recounting my mother’s memories back to her, in order for us to locate the site of her memories. The work involved a lot of missteps, as our combined memories as reliable sources slipped in-between moments of clarity and other moments of uncertainty.

LS: When The Mother of All Journeys was exhibited at the Amelia Johnson Contemporary there seemed to be a clear emphasis on the spatial configuration of the work, and how it was situated both on the walls as well as within the gallery space itself. What influenced this presentation?

DL: Due to the complexities of the project, we divided the exhibition into three parts, using walls as demarcations to define geographic differences. The work involved journeys to China, Hong Kong and parts of Northern England, and so their separation in terms of exhibition display felt necessary.

LS: Do you think it is important for photographic work, work that is typically flat surfaced and wall supported, to be displayed in a more spatially configured and engaging way? And are there particular kinds of spaces you like to work with?

DL: I think it is important to work with a given space, responding to the architecture in site specific ways. I find it exciting to display my work in different ways depending on the site, and how the light moves across that space over the course of the day. Sometimes a long wall lends itself to displaying work in a linear fashion. Other times, if a space has a variety of rooms, the same body of work can be reconfigured in other interesting ways.

One of the most interesting spaces I have enjoyed working in recently is Birkenhead Market, where I occupied several market units to display my trilogy and several other pieces. I was so excited to install my work in such a context, as market aesthetics always reminds me of my childhood, since the place I grew in was stones-throw away from Hong Kong’s famous street markets.

LS: After having first-hand experience studying under you at Falmouth University, where you are Senior Lecturer in Photography, I know how you really push students to produce unique and meaningful work. Do you ever find that being in your position, surrounded by students, that you look at things differently based on conversations you have with them or work you see?

DL: I am beginning to see more students working on projects but unable to discuss the meaning behind what they have spent months doing. in their works, there is a trend in projects that appear autobiographical; political without recognising that’s what they are doing; and most recently, a return to documentary traditions in landscape photography. These themes and trends do not feel incidental to me.

From my vantage point, the reason why I think students find it difficult to articulate their projects is very much related to Brexit. There is so much uncertainly to being a student today. They question the value of their work, they are unsure if they are making good work, they are concerned about their futures and they don’t know how to feel about leaving the EU. It is no wonder they find it difficult to discuss the meaning behind their images. Brexit has formed an invisible backdrop to the contexts surrounding the times by which today’s students are being educated.

LS: Given your position you must of course pay close attention to how the arts are viewed by the wider educational sector, and indeed the government. What does the current climate look like for educating students within creative subjects?

DL: I hope educational establishments continues to allow creative subjects to keep pushing the boundaries of what art is. I worry about the professionalisation of creative courses and just hope we allow students the space to be inquisitive, the time to find their voice, and the freedom to try out new ideas. I go back to the notion of identity and wanting to be understood as a verb rather than a noun. In that sense, I hope our students will develop the kind of inquisitive minds that allows them to be more fluid in the way they operate.

Stephen Fry once said “Oscar Wilde said that if you know what you want to be, then you inevitably become it – that is your punishment, but if you never know, then you can be anything. There is truth to that. We are not nouns, we are verbs. I am not a thing – an actor, a writer – I am a person who does things – I write, I act – and I never know what I am going to do next. I think you can be imprisoned if you think of yourself as a noun.”

LS: And finally, as for your personal practice is there anything you are currently working or investigating?

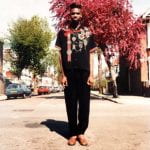

DL: I am developing new work, something autobiographical, delving into my own youth, when I was immersed in black youth culture. I’m looking at developing work connected to reggae and dub music.