From Minstrels to Mammies

By Abigail Emm (15th July 2021)

“The negative depiction of black women as domineering matriarchs or exotic sexual objects was created, and still is perpetuated, by white (usually white male) social scientists, and even by a few black male social scientists trained by the … images of hyper-sexuality and overbearingness often merge to symbolize the black woman” (St. Jean & Feagin, 1998: 6)

Introduction

From minstrel shows to mammies, black people, and more specifically, black women in film, have been portrayed in a damaging light. Caricatures that echo the dehumanisation of black people have been at large throughout the history of American film. With the Black Lives Matter movement sparking necessary conversation on issues surrounding systemic racism and white privilege, it’s essential that we turn our focus to the issues faced by black women. Often rejected from feminist spaces for being black, and from black spaces for being female (Crenshaw 1989: 140), black women’s voices need to be elevated more than ever. Throughout this Literature Review I will be exploring the existing material regarding black female representation in American film, looking at the history and contexts of certain stereotypes, and at how portrayals have progressed over the years.

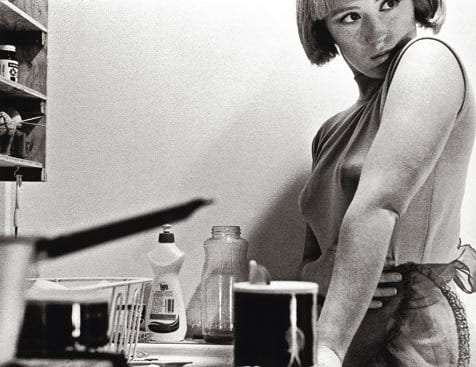

Intersectionality: The Male and White Gazes

Due to belonging to two minority groups, black women’s struggle for representation, both on screen and behind it, is made all the more difficult. Even white women, whose experience of womanhood is made easier by their whiteness, have fought and continue to fight sexist portrayals. Most notable is Cindy Sherman’s photographic project Untitled Film Stills, (Figure 1) where she transformed herself into common tropes such as the femme fatale and the suburban housewife, playing with the concepts of the male gaze and voyeurism.

The male gaze is a concept introduced by Laura Mulvey in her essay Visual Pleasures and Narrative Cinema and highlights the objectification and sexualisation of women for the purpose of the male scopic drive (the pleasure in looking). The woman’s role is to sustain the “fantasies and obsessions” of men, having no authority and taking a “passive” approach in looking, as opposed to the “active” view of the male (Mulvey 1989: 15-19). John Berger described this concept years prior, as “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” (Berger 1972: 47).

The white gaze, as explored in an article for The Guardian, “traps black people in white imaginations” (Grant 2015), limiting them to their expected roles and undermining their prerogative by forcing them to be a complicit aid for their white lead.

Statistics of Race and Gender Representation in Hollywood Film

The representation of race and gender in film has been well documented throughout the years. A study by US Cannenberg stated that out of the top 100 grossing films of 2019, one third didn’t include a speaking or named black female character, in contrast with the mere 7% of films that omitted their white counterpart (Smith et al. 2020). The UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report for the same year concluded that only “3 out of 10 lead actors in film are people of colour”, which shows the underrepresentation of racial minorities, especially when we consider that they make up more than “40% of the US population” (Hunt and Ramón 2020).

There is a statistical inequality between male and female black filmmakers, due to what Ed Guerrero describes as the “triple oppression” for black women: “independent vision, race and gender” (Guerrero 1993: 174). Due to both women and black people’s experiences being undermined in society, the lack of voice given to people belonging to both minorities is large.

The Bechdel, DuVurnay and Shukla Tests

In order to highlight the lack of representation of minorities in film, several ‘tests’ have been created to determine if films are being inclusive in both their casting and their portrayal. The test that initiated these measures is the Bechdel test, the premise of which was initially introduced as a feminist joke in a comic book. Despite its unserious origins, it’s now used as a tool of evaluation.

To pass the Bechdel test, the following criteria must be met: at least two female characters must exist with speaking roles, as well as conversing with each other about something other than a man (Bechdel ca. 1985. The Rule – Dykes to Watch Out For). (Figure 2) Some interpretations also require the women to be named characters. Despite its popularity, it has been heavily critiqued due to its low standards for female dialogue – it’s argued that audiences should instead be analytical of how their dialogue is perceived by other characters (O’Meara 2016), and if they make choices that “drive their own stories” (Ellis 2016).

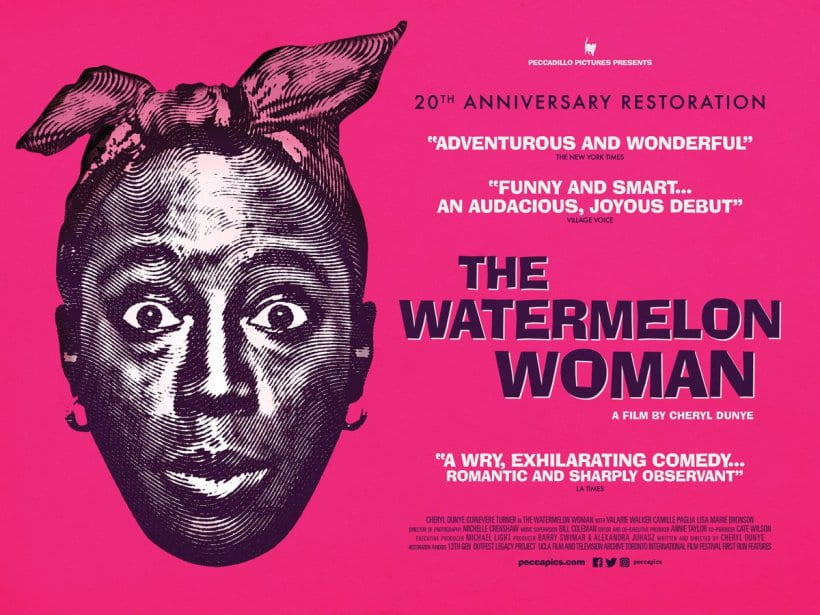

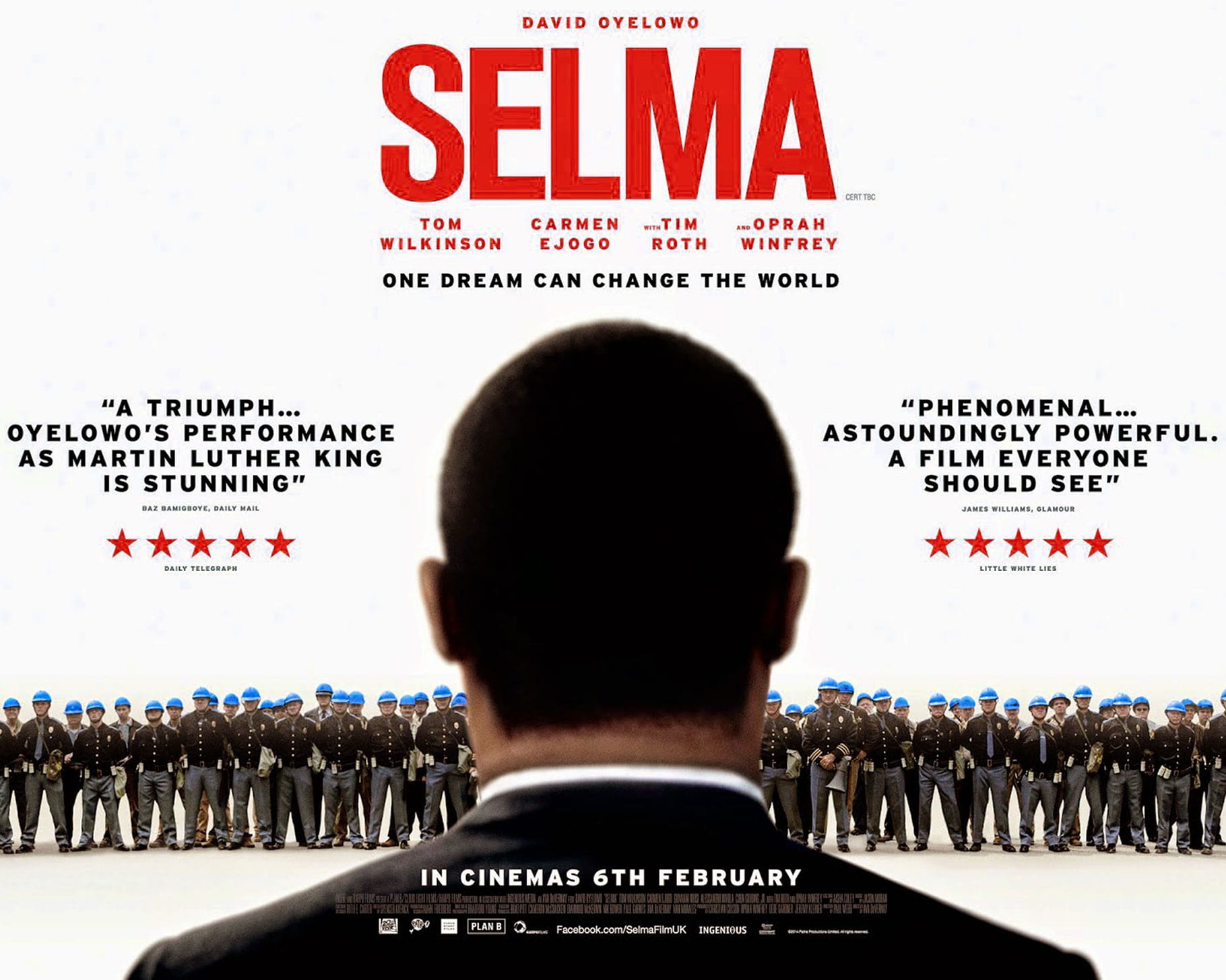

From the Bechdel test came the DuVurnay and Shukla tests, the former coined by a movie critic due to the lack of Oscar votes for Selma, a movie about civil rights created by a black female director. (Figure 3) It was named after the director herself, with its aim to highlight racial inequality, the premise being that African Americans should be depicted as having “fully realized [sic] lives rather than serve as scenery in white stories” (Dargis 2016). With an emphasis on giving people of colour conversations outside of their racial identity, the Shukla test requires “two ethnic minorities talk to each other for more than five minutes about something other than race” (Shukla 2013). Unlike the Bechdel test, the analysis of films that meet the criteria of the DuVurnay and Shukla tests has been mostly unexplored, with only The Guardian reporting that just three of 2016’s best picture Oscar nominees had passed the Shukla test (Latif and Latif 2016). However, the mere invention of these measures highlights the fact that racial minorities in film are not given the representation or portrayal that is necessary.

“The new stereotype played to White perceptions of Black personalities who, in the vernacular of the era, ‘knew their place’ in American society. Blacks now appeared in movies for the purpose of entertaining White audiences within the context of social limitations… When in movie character, Blacks were subservient to Whites as maids, mammies, domestics, and sidekicks” (Clint et al, 2013: 73)

Stereotypes of Black Women: The Mammy

To understand the contemporary portrayal, we must first look at the origins of the main stereotypes that has dominated films from the beginning: the mammy, the jezebel, and the sapphire. Characterised as being jolly, middle-aged, overweight, dark-skinned and pertaining to have or evoke no sexual desire, the mammy’s sole purpose is to care for the white family she is a servant for (Jewell 1993: 39-39; West 1995: 459; Harris-Perry 2011: 73). Stemming from the Southern states, this stereotype bases itself on black women who served during the antebellum era (McElya 2009: 4). However, this greatly contrasts with the reality of black servants at the time as the majority would have been young and slim, the latter being due to poor diets (ibid, Pilgrim 2000, Jones 2019). These attributes were created to present black women as being against the epitome of white womanhood (Jewell 1993: 39-40, Pilgrim 2000) creating a further division between black and white woman.

As discussed in From Mammy to Miss America and Beyond, and quoted in Sister Citizen, this portrayal was created as pro-slavery propaganda by presenting black slaves as being “happy and content with their duties” (Jewell 1993: 38), despite the fact that these women lived with the “constant threat of physical and sexual violence” (2011: 72).

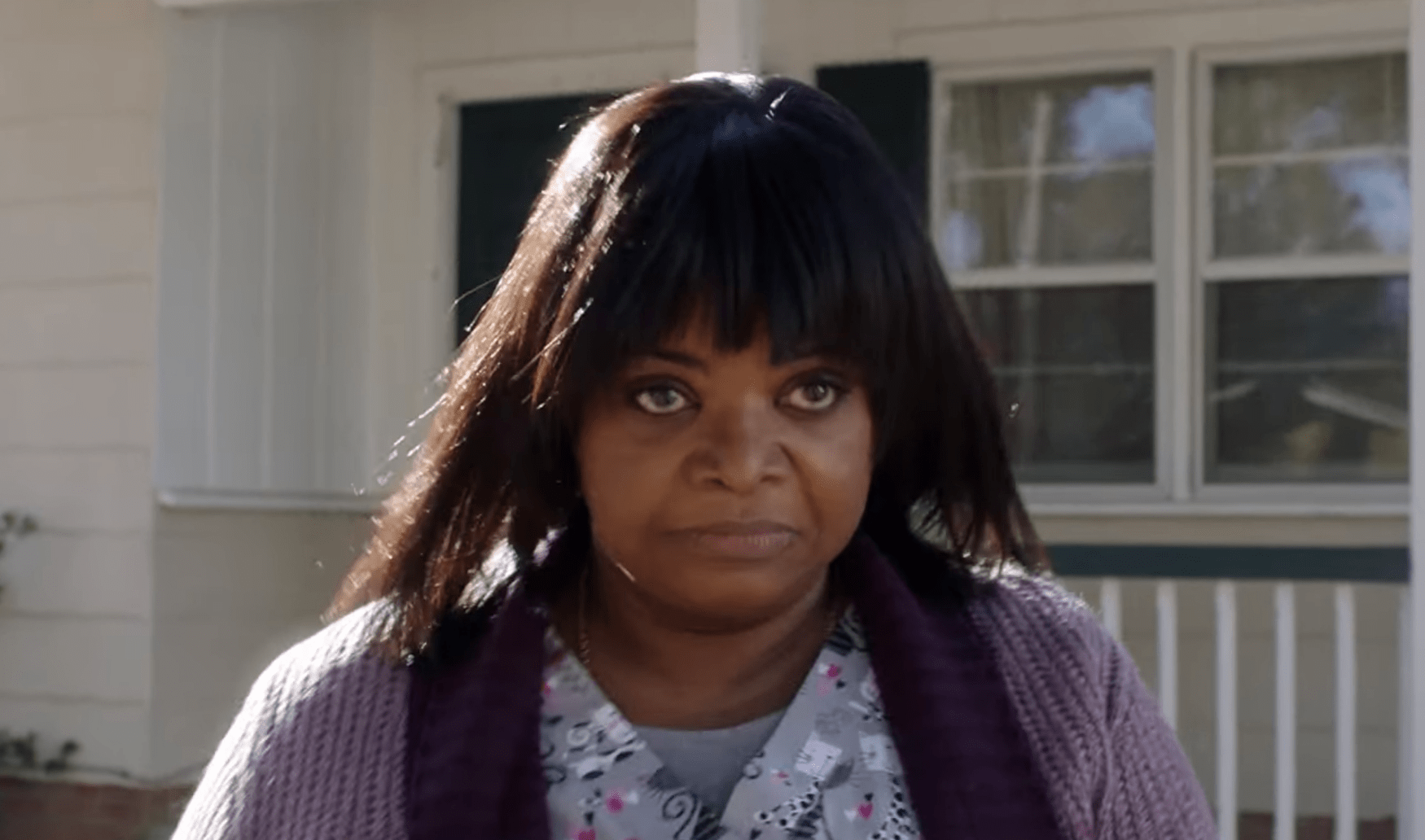

The most notable depiction of this stereotype is seen in the 1939 film Gone with the Wind, where the character Mammy is seen as protective and devoted towards the white family in which she serves (2009: 3). (Figure 4) This damaging stereotype can be seen in many movies, including The Help (2011) and the Big Momma anthology (2000-2011). However, in recent film this caricature has been subverted, creating a new narrative. The 2019 horror film Ma contorts this depiction of black women – initially starting out as a considerate motherly figure by inviting a group of young people into her home, the character Ma takes a sharp turn, becoming vengeful when they rebel against her rules (Jones 2019). (Figure 5)

Ma’s “terror, cruelty and vengeful rage are reserved exclusively for white women and children” (ibid), greatly contrasting with Gone with the Wind’s Mammy, whose care is exclusive for her white family. Despite critics’ analysis of this depiction of a subverted stereotype, the white director Tate Taylor denies the correlation between Ma and the attributes of the mammy trope in his own film (White 2019), highlighting the ignorance often held by white people when it comes to stereotypes of minorities in film.

Black women, however, are all too familiar with their representation, with a 2003 study reporting that 97% of the black women interviewed were ‘‘aware of negative stereotypes of African American women”, with 80% stating they have been affected by “persistent racist and sexist assumptions” (Charisse Jones and Kumea Shorter-Gooden, cited in Harris-Perry 2011: 35). Despite this, as Carolyn West discusses in Mammy, Jezebel, Sapphire and Their Homegirls, some black women find comfort in seeing the “warmth and resilience” of the mammy, including when placed on memorabilia (West 2008: 287). This opinion is not widespread however, as these depictions were used to “dehumanize [sic]” (Brown 2019) and are most often deemed entirely offensive.

Stereotypes of Black Women: The Sapphire & The Jezebel

Depicted as “the angry black woman” (Aljazeera 2020), the stereotype of the sapphire was based on the character of the same name in the mid 20th century show Amos ‘n’ Andy. “Hostile [and] nagging” (2008: 296), she is shown to emasculate the men around her, further reiterating the belief that black women aren’t as desirable as white women. (Figure 6) It was popular during the 1970s’ blaxploitation era of film, in which black people were depicted as being promiscuous, rebellious and criminal (Pilgrim 2002).

“The notion of the angry Black woman was a way — is a way — of trying to keep in place Black women who have stepped outside of their bounds, and who have refused to concede the legitimacy of being a docile being in the face of white power,” (Dyson in Ryzick et al, 2020)

In modern film, the sapphire transforms into the trope of the ‘sassy black friend’, often outspoken with unfiltered speech. She can be seen in Wanda Sykes character in the Bad Moms anthology (2016-2017), in which she acts as a humorously unprofessional therapist by insensitively giving relationship advice (Lucas and Moore 2016).

This trope is seemingly more prominent in comedy television shows than it is in movies, with these characters’ main contribution being one-liners to entertain the white protagonist, and having no story of their own, such as Donna Meagle from Parks and Recreation whose catchphrase ‘treat yo’ self’ has gained popularity (Mylrea 2017).

Hyper-sexual and possessing lighter skin and European features, jezebels adhere to the “sex objectification requirement of white womanhood”, greatly contrasting with the sexless attributes of the mammy, and the masculine aggressiveness of the sapphire (Jewell 1993: 46). The only power a jezebel holds is through her slim, attractive body, as this enables her to seduce men (Aljazeera 2020). Stemming from the rape and sexual assault of female slaves from male slaveowners, the jezebel has been used to cover-up these crimes by presenting black women as always having “desired sex”, infiltrating the belief that these sexual encounters were consensual (2008: 294), creating further ownership of white men over black female bodies.

The Objectification of Black and Female Bodies

The objectification of black bodies is historically evidenced by anthropometric photography which initiated during the 1860s. (Figure 7) Black people were photographed against grids in order to calculate their “physical characteristics” (Cohen 2015: 61). It’s also important to note Martha Rosler’s video piece Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained on the dehumanisation of women’s bodies (Rosler 1997), linking to anthropometric studies by showing a woman being clinically measured. This reiterates the increased oppression faced by black women due to both their racial and gender identities being subjected to objectification.

The First High-Profile Black Superhero Movie: Black Panther

“A commentary on African lives with minimal interest in, or need for, the approval of the white gaze” (White 2018), 2018’s Black Panther is one of the top 10 highest grossing films of all time (Hughes 2018). (Figure 8) Having a predominantly black cast and a diverse set of roles and for female characters, Black Panther passes the Bechdel, DeVurnay and Shukla tests. In an interview with Variety, the actress Lupita Nyong’o stated that the director purposefully created roles that would show the “influence” of women, showing eagerness to represent them as diverse individuals (Variety 2018).

Women can be seen physically protecting the male protagonist along with dominating the technological field (ibid), showing strength and leadership in a positive light, and diverging from the emasculatory demeanour of the sapphire. This creation of well-rounded characters subverts the male gaze, whilst colonialist viewpoints are defied by showing African tribes as progressive. The authority is passed over to black women themselves, something rarely seen in American film.

Overall, it can be said that the roles available to black women are slowly becoming more diverse. Shunning stereotypes rooted in slavery propaganda and trading them for complex, influential characters, the American film industry is starting to give black women their own voice. However, lead roles for black women are still scarce, instead going to their male or white counterparts.

Conclusion

“We need to be more aware of the persistence of stereotypes affecting Black girls and women – and avoid repeating those mistakes when making writing, casting, and other content production decisions. While it is encouraging to see some positive trends, it’s clear that much more work needs to be done to ensure that women of all backgrounds have the same opportunities when it comes to being depicted on screen.” (Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, 2021)

The notable academic research on this topic was created during the 1980s to early 2000s, and has taken a small decline since then, with newspaper and magazine articles becoming more prominent than academic journals or studies, the latter not gaining as much attention as reports in earlier years. With the rise in the acceptance of the LGBT community, and the acknowledgement of the struggles faced by those with disabilities, there is surprisingly little research about the representation of black women who also identify with these labels. Seeing this lack of research, there is scope for an investigation into how these additional components to one’s identify affect people’s casting, perception, and representation in film.

follow Abigail Emm on instagram

References

- Aljazeera. 2020. Mammy, Jezebel and Sapphire: Stereotyping Black Women in Media. [Video]. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/program/the-listening-post/2020/7/26/mammy-jezebel-and-sapphire-stereotyping-black-women-in-media/. [accessed November 2020].

- BECHDEL, Allison. 1985. The Rule – Dykes to Watch Out For. Available at: https://dykestowatchoutfor.com/the-rule/. [accessed November 2020].

- BERGER, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing. (First edn). London: British Broadcasting Cooperation and Penguin Books.

- BROWN, Elisha. 2019. ‘Mammy Jars Mock Black People. Why are they Still Collected?’. New York Times (Online) Mar 27, [online]. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2197931327. [accessed November 2020].

- CLINT, C. WILSON, I, GUTIRREZ, F. & CHAO, L.M. (2013) Racism, Sexism and the Media London: Sage

- COHEN, Janie. 2015. ‘Staring Back: Anthropometric-style African Colonial Photography and Picasso’s Demoiselles: Anthropometric Photography and the Anthropometric Style’. Photography & Culture, 8(1), 61-63.

- CRENSHAW, Kimberle. 1989. ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics’. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1).

- DARGIS, Manohla. 2016. ‘Sundance Fights Tide With Films Like ‘The Birth of a Nation”. New York Times (Online). Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/30/movies/sundance-fights-tide-with-films-like-the-birth-of-a-nation.html. [accessed November 2020].

- ELLIS, Samantha. 2016. ‘Why the Bechdel Test Doesn’t (always) Work’. The Guardian (London) Aug 20, [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/womens-blog/2016/aug/20/why-the-bechdel-test-doesnt-always-work. [accessed November 2020].

- Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media (2021) ‘New Research on Portrayals of Black Women in Hollywood Signals Progress, But Colorism Persists’ in Cision PR Newswire 2nd March 2021 Available at https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-research-on-portrayals-of-black-women-in-hollywood-signals-progress-but-colorism-persists-301238238.html [accessed March 2021].

- GRANT, Stan. 2015. ‘Black Writers Courageously Staring Down the White Gaze – this is why we all must read them’. The Guardian (London) Dec 31, [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/dec/31/black-writers-courageously-staring-down-the-white-gaze-this-is-why-we-all-must-read-them. [accessed November 2020].

- GUERRERO, Ed. 1993. Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film. Temple University Press.

- HARRIS-PERRY, Melissa. 2011. Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- HUGHES, Mark. 2018. ”Black Panther’ is Now the 10th Highest Grossing Film of all Time’. Forbes Apr 2, [online]. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/markhughes/2018/04/02/black-panther-is-now-the-10th-highest-grossing-film-of-all-time/?sh=2fcf02816a40. [accessed 2 December 2020].

- HUNT, Darnell and Ana-Christina RAMÓN. 2020. Hollywood Diversity Report 2020. UCLA.

- JEWELL, K. S. 1993. From Mammy to Miss America and Beyond Cultural Images and the Shaping of US Social Policy. (First edn). London: Routledge.

- JONES, Ellen E. 2019. ‘From Mammy to Ma: Hollywood’s Favourite Racist Stereotype’. BBC May 31, [online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190530-rom-mammy-to-ma-hollywoods-favourite-racist-stereotype. [accessed November 2020].

- LATIF, Nadia and Leila LATIF. 2016. ‘How to Fix Hollywood’s Race Problem’. The Guardian (London) Jan 18, [online]. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1758816112. [accessed November 2020].

- LUCAS, Jon and Scott MOORE. 2016. Bad Moms | Couples Therapy Clip.

- . Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcPZMmvFcdY. [accessed November 2020].

- MCELYA, Micki. 2009. ‘Introduction: The Faithful Slave’. In Clinging to Mammy: The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- MULVEY, Laura. 1989. ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’. In Visual and Other Pleasures. (2nd edn). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 14-27.

- MYLREA, Hannah. 2017. ‘Treat Yo’ Self! ‘Parks And Rec’ fans celebrate the best day of the year’. NME. Available at: https://www.nme.com/news/treat-yo-self-day-parks-recreations-2149736. [accessed November 2020].

- O’MEARA, Jennifer. 2016. ‘What “The Bechdel Test” doesn’t tell us: examining women’s verbal and vocal (dis)empowerment in cinema’. 16(6), 1120-1123.

- PILGRIM, David. 2002. ‘Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia: The Jezebel Stereotype’. Available at: https://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/jezebel/. [accessed November 2020].

- PILGRIM, David. 2000. ‘Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia: The Mammy Caricature’. Available at: https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/mammies/. [accessed November 2020].

- RYZIK, M. UGWU, R. PHILLIPS, M, & JACOBS, J. (2020) ‘When Trump Calls a Black Woman ‘Angry,’ He Feeds This Racist Trope’ in The New York Times 14th August 2020 Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/14/arts/trump-black-women-stereotypes.html [accessed November 2020]

- ROSLER, Martha. 1977. Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained. [Video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b91_vZ8TauM. [accessed November 2020].

- SHUKLA, Nikesh. 2013. ‘After the Bechdel Test, I Propose the Shukla Test for Race in Film’. NewStatesman Oct 18, [online]. Available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/2013/10/after-bechdel-test-i-propose-shukla-test-race-film. [accessed November 2020].

- SMITH, Stacey L., Marc CHOUEITI and Katherine PIEPER. 2020. Inequality in 1,300 Popular Films: Examining Portrayals of Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBTQ & Disability from 2007 to 2019. USC Annenberg: USC Annenberg.

- ST JEAN, Y & FEAGIN, J.R. (1998) Double Burden: Black Women and Everyday Racism London: Routledge

- Variety. 2018. ‘Black Panther’ – the Women of Wakanda. [Video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-2dYwsmVy6c. [accessed November 2020].

- WEST, Carolyn. 2008. ‘Mammy, Jezebel, Sapphire, and their homegirls: Developing an “oppositional gaze” toward the images of Black women’. In Lectures on the Psychology of Women. McGraw Hill, 286-229.

- WEST, Carolyn M. 1995. ‘Mammy, Sapphire, and Jezebel: Historical images of Black women and their implications for psychotherapy’. Psychotherapy Theory Research & Practice, 32, 458-466.

- WHITE, Armond. 2019. ‘Ma’s Black-Mammy Stereotypes Capture the Illiberal Spirit’. National Review Jun 7, [online]. Available at: https://www.nationalreview.com/2019/06/movie-review-ma-revenge-satire-black-mammy-stereotype/. [accessed November 2020].

- WHITE, Renée T. 2018. ‘I Dream a World: Black Panther and the Re-Making of Blackness’. New Political Science, 40(2), 421-427.