Can It Be Challenged by New Technologies?

By Maddy Baron Clark (1st October 2021)

‘To gaze implies more than to look at – it signifies a psychological relationship of power, in which the gazer is superior to the object of the gaze’ (Schroeder, 1998, p.208)

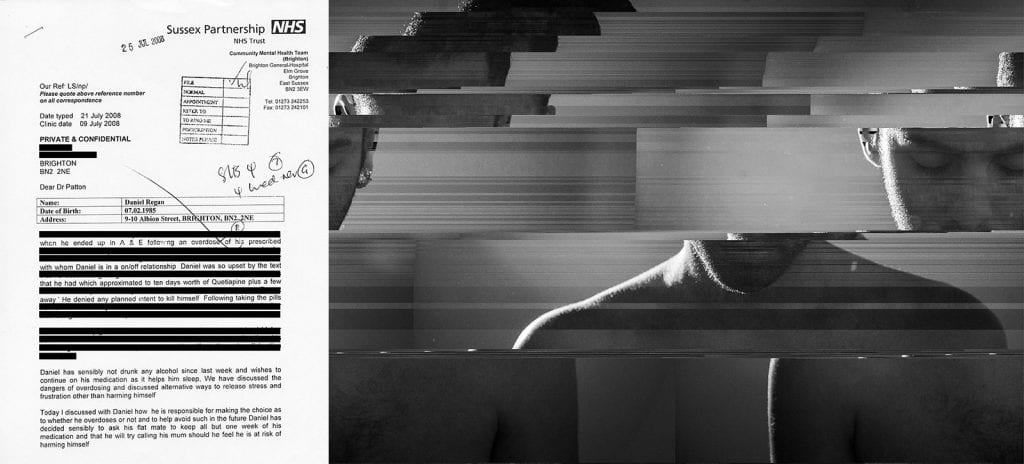

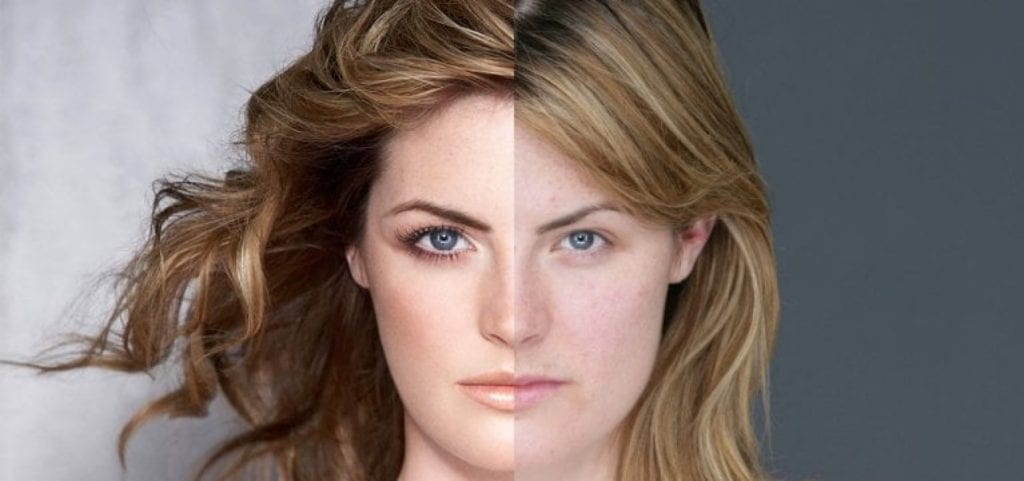

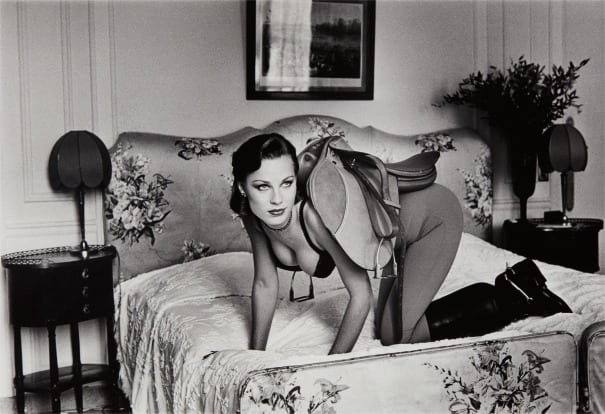

In Visual and Other Pleasures (Mulvey 1989:19) Mulvey proposes the idea of the male gaze, describing woman as playing a ‘traditional exhibitionistic role’ in which ‘male spectators… can project their fantasies onto’ (1989:19) in cinema. The male gaze is established as a common occurrence in historical and contemporary media. Helmut Newton employed the male gaze in most of his work, often depicting women in the ‘exhibitionistic role’ (1989:19) that Mulvey describes (Figure 1). Moreover, Peter Schjeldahl employs the concept of the male gaze with reegard to Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits (Figure 2), describing them as ‘fiercely erotic’ (cited Meagher 2002:21). In these examples the male gaze appears well established.

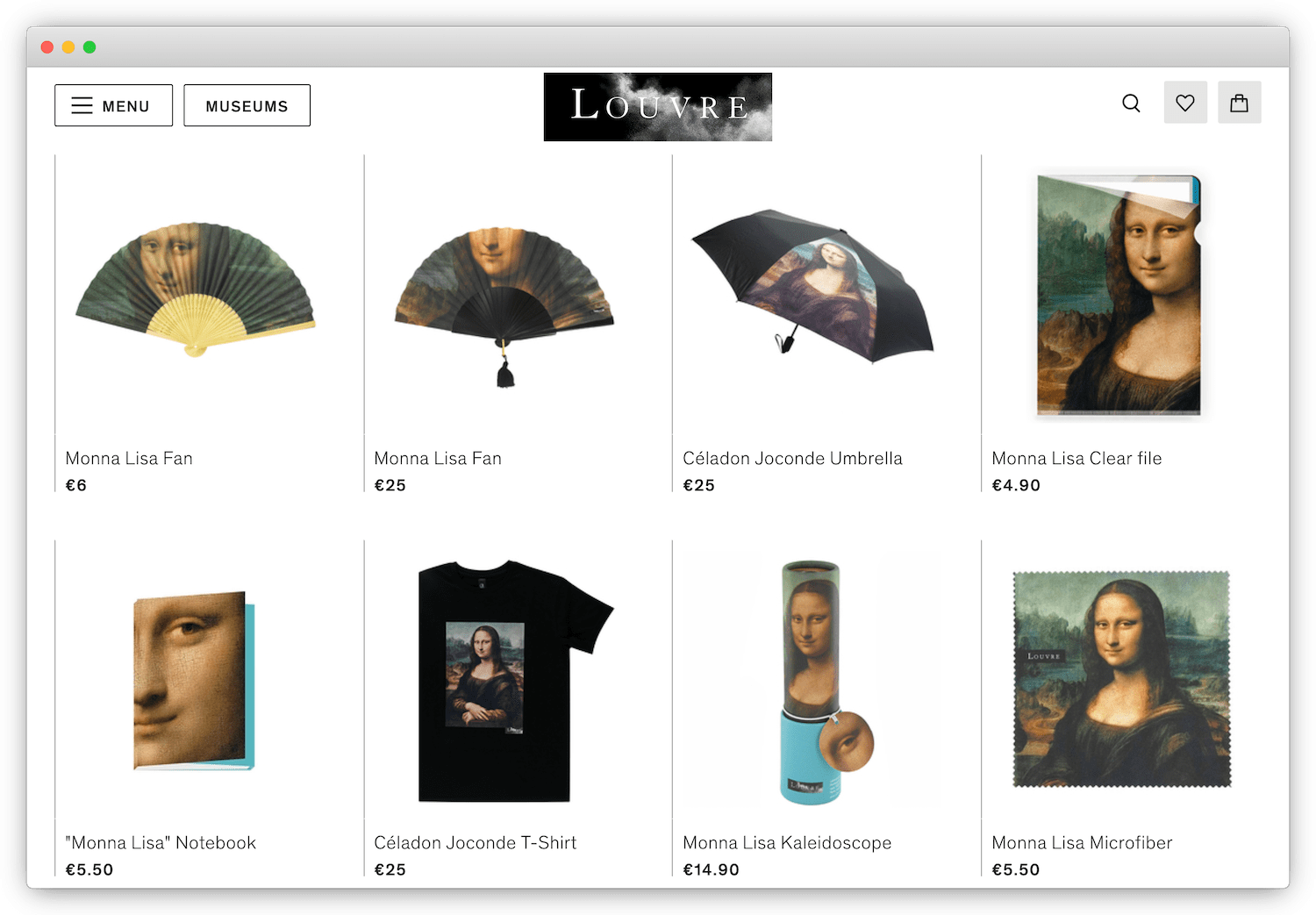

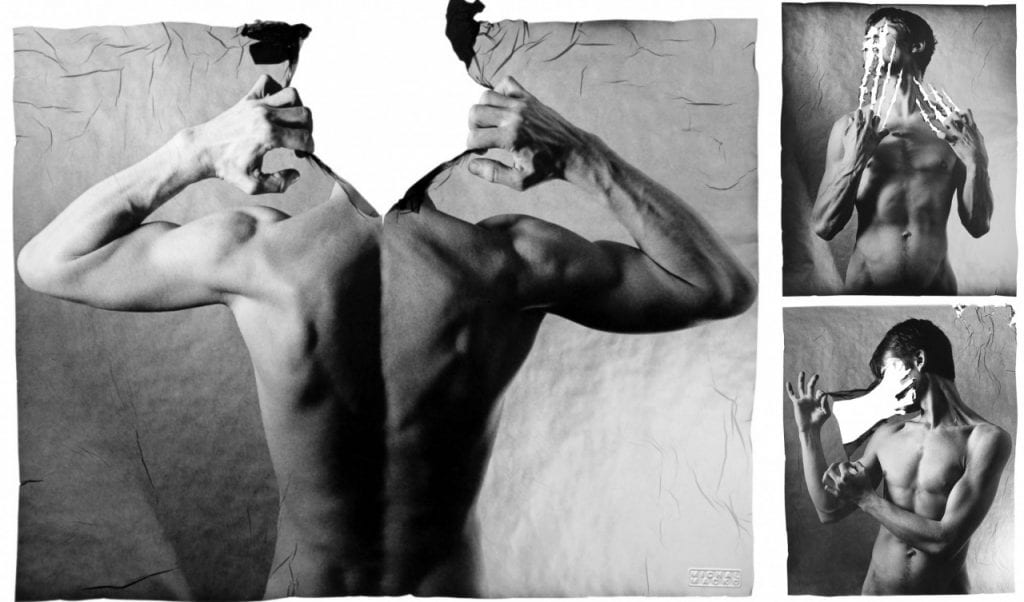

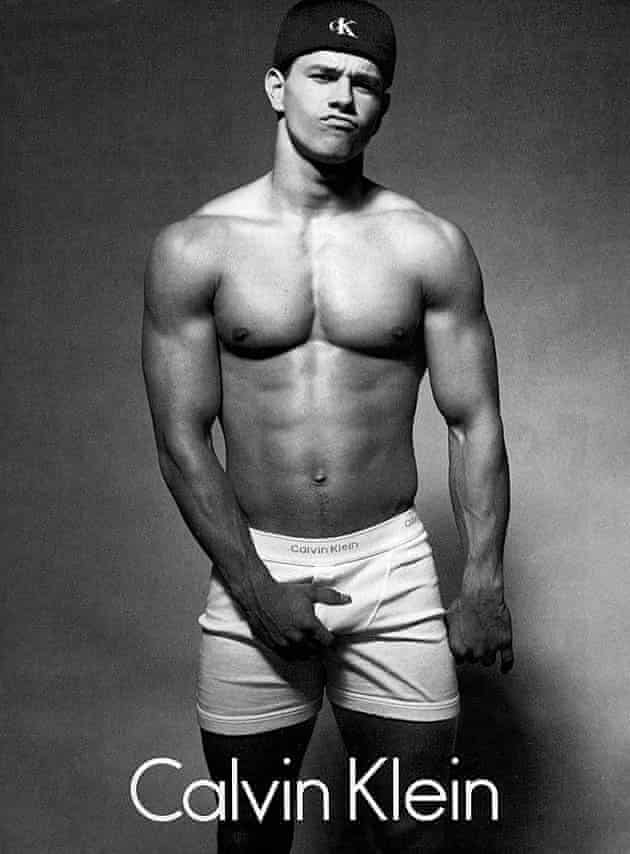

In contemporary contexts however it can be argued the gaze is shifting and that Mulvey’s theory is outdated. Susan Bordo described Mulveys concepts ‘in the year 2015… seem[ing] obsolete’ (Bordo 2015). In the context of western contemporary society, objectifying bodies for profit is standard. Bordo points out that Mulvey ignores the consumerist culture we live in, and how the ‘eroticisation of the male body became big business thanks to the genius of Calvin Klein and other designers’ (Bordo 2015) (Figure 3). Thomas and Ahmed reinforce this: ’the displayed male bodies since the 80s… [are] offered to the gaze of women and heterosexual men in the new men’s magazines and fashion magazines’ (cited Whiteway 2017). In all instances the objectification of the body is used to target consumers, but equally allows for the rise of other forms of the gaze.

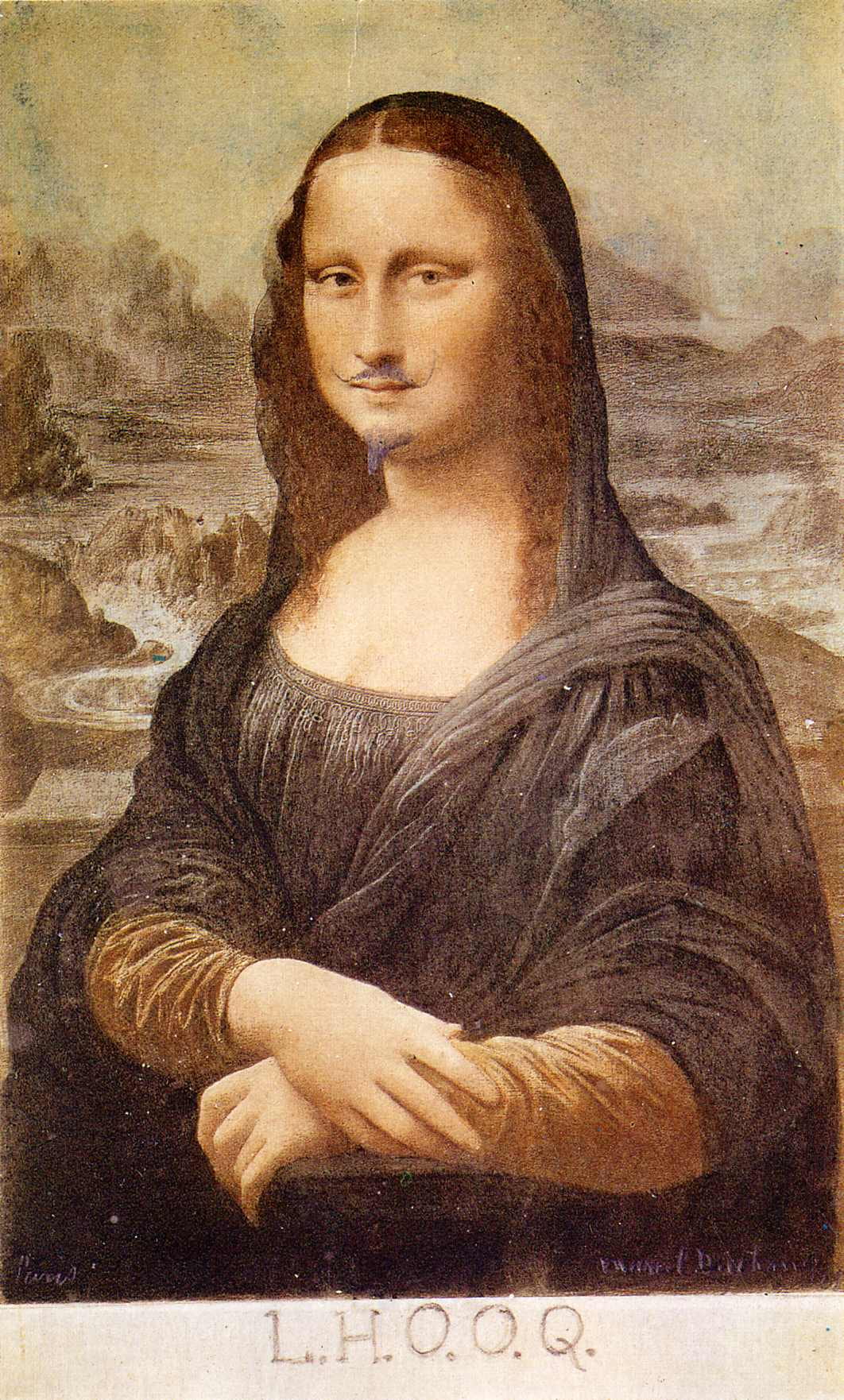

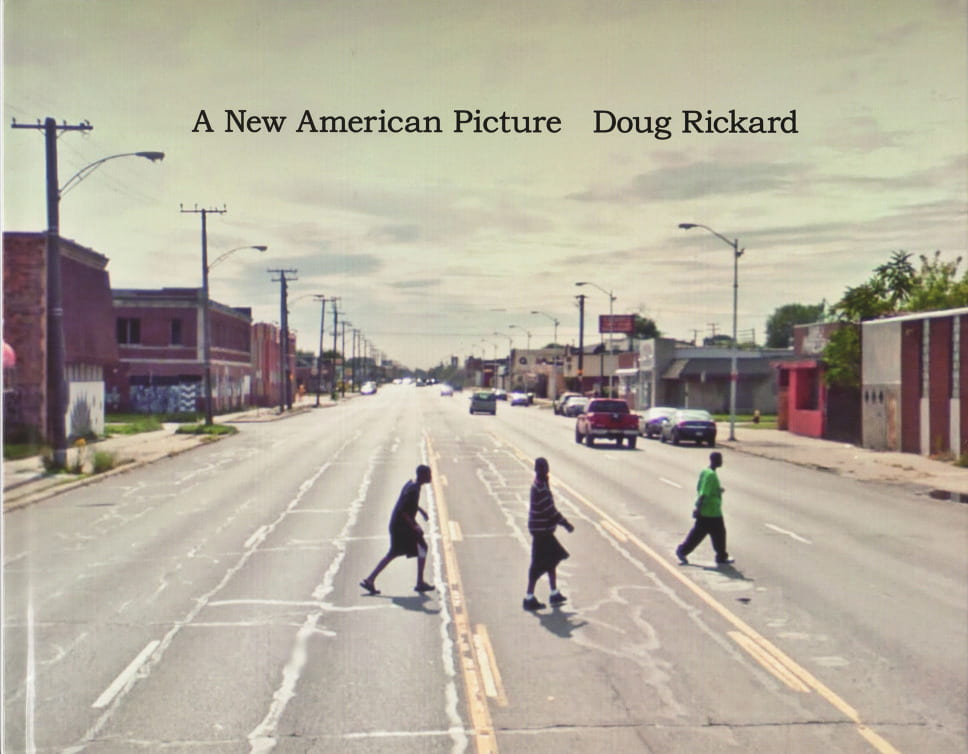

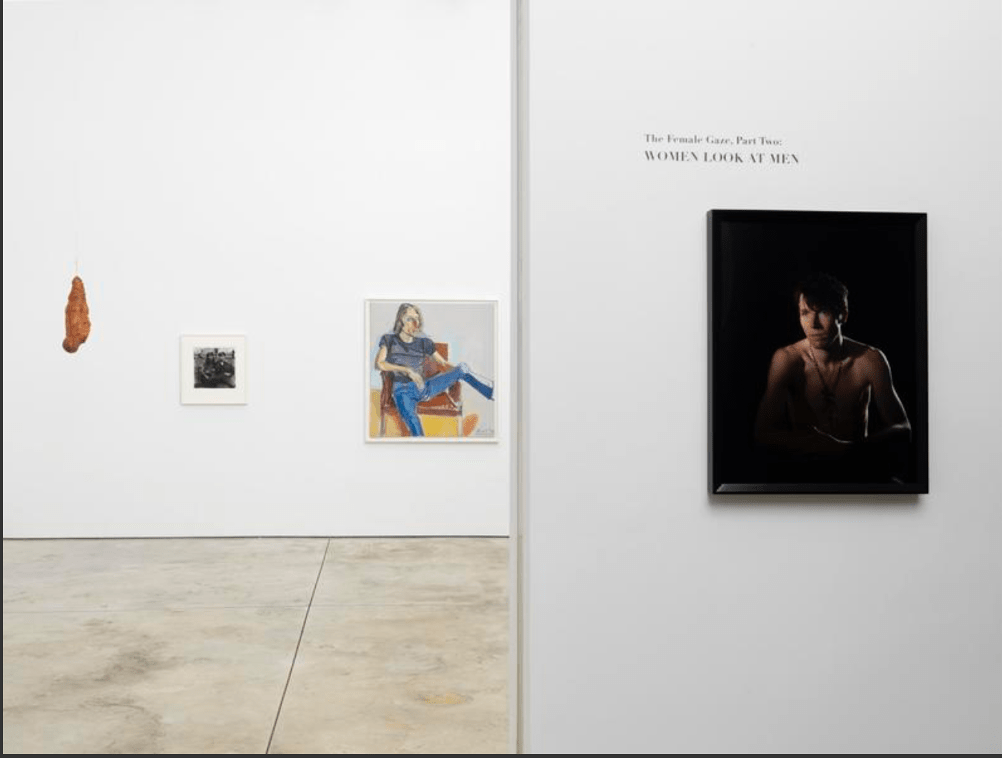

Similarly, culturally, there are female artists which create work using the gaze (Figure 4). The exhibition Women Looking at Men (Cheim 2016) features thirty-two women artists, specifically objectifying the male body and giving rise to the female gaze against Mulvey’s purely male gaze

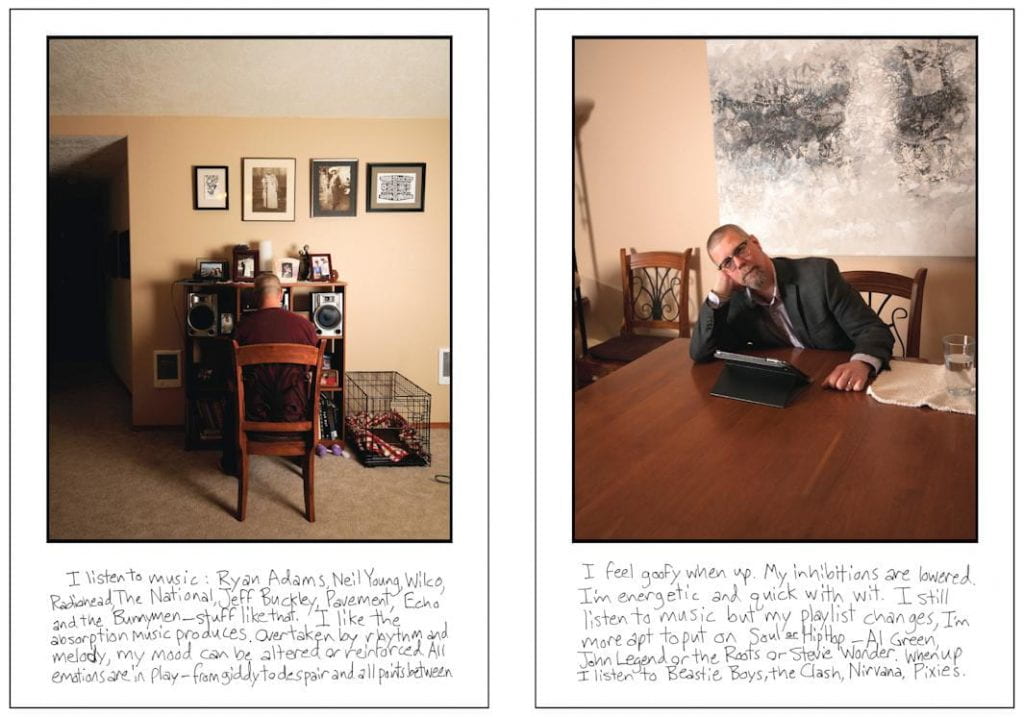

Mulvey also ignores pornography catered to the LGBT+ community which can objectify all genders. The Chronicle’s essay states ‘the notion of the lesbian gaze has gained currency’ and argues ‘even the neat division of people into male and female seems, to many people, archaic.’ (The Male Gaze in Retrospect 2015). This idea of division being archaic is brought up in Legacy Russel’s Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. Russel aims to strike back at existing ‘in a binary system’ using the rise of the internet and online presence (Russel 2020:7) focusing on being ‘anti-body, resisting the body as a coercive social and cultural architecture’ (2020:91) and thus resisting all forms of the gaze. Russel uses non-binary artist Victoria Sin as an example: ‘Their body shatters the shallow illusion as to any harmony or balance that might be offered up within the suggestive binary of male/female’ while ‘celebrating their queer body as necessarily visible… a calculated confrontation.’ (2020:59) (Figure 5).

Mulvey’s 1989 theory is far from incorrect: there are still many instances where the male gaze is employed. Nonetheless, Mulvey fails to recognise the expansion and evolutions of these alternative gazes and those who confront them in a contemporary context

Case Study: Miquela Sousa (@LilMiquela)

‘There are circumstances in which looking itself is a source of pleasure, just as in the reverse formation, there is pleasure in being looked at’ (Mulvey (1975) in Hall & Evans, 2003, p.381)

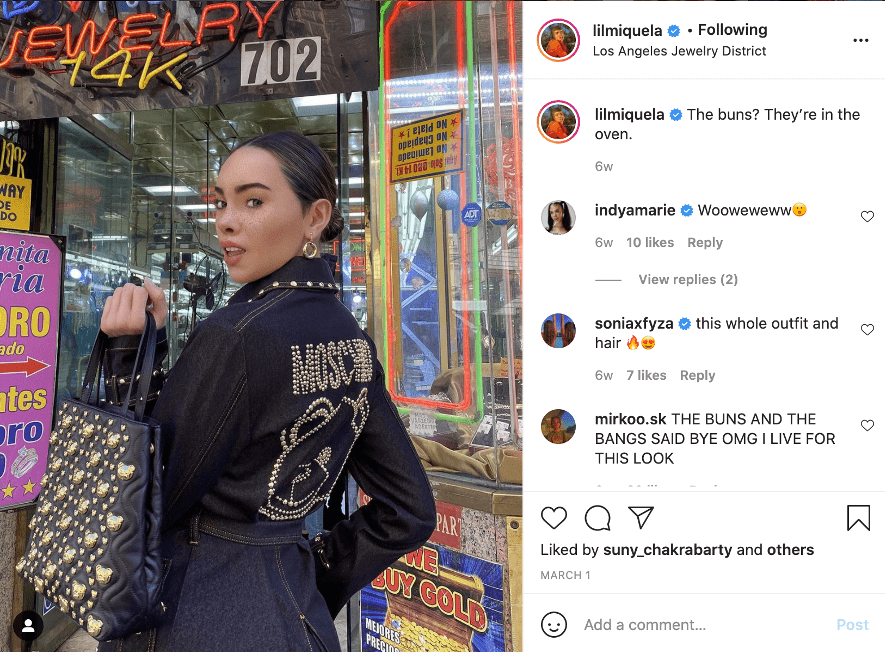

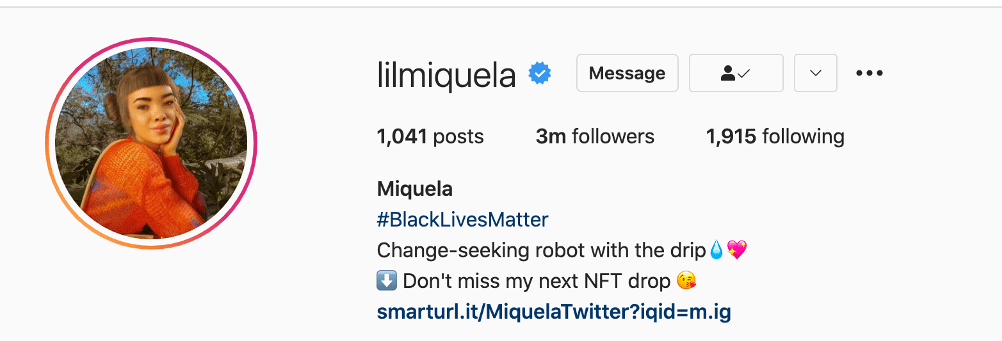

Miquela Sousa, otherwise known as @LilMiquela on Instagram, is a CGI virtual influencer created by startup Brud (Jackson 2018) with over three million followers on Instagram. Lil Miquela posts frequently, promoting brands and ‘spends her time taking selfies and hanging out with her equally-cool, but actually real friends’ (Cadogan 2018) her behaviour mimics a celebrity social media influencer (Figure 6)

Lil Miquela’s creators, Brud, claim she is ‘a champion of so many vital causes, namely Black Lives Matter and the absolutely essential fight for LGBTQIA+ rights in this country’ (cited in Russel 2020:93). Russel notes that Lil Miquela is an example of the ‘anti-body’ (2020:93) in her manifesto. Lil Miquela only exists as an online avatar and is seen promoting social change online (Figure 7) where she has #BlackLivesMatter in her bio and supports social causes on her instagram stories (Figure 8), backing Russel’s concept.

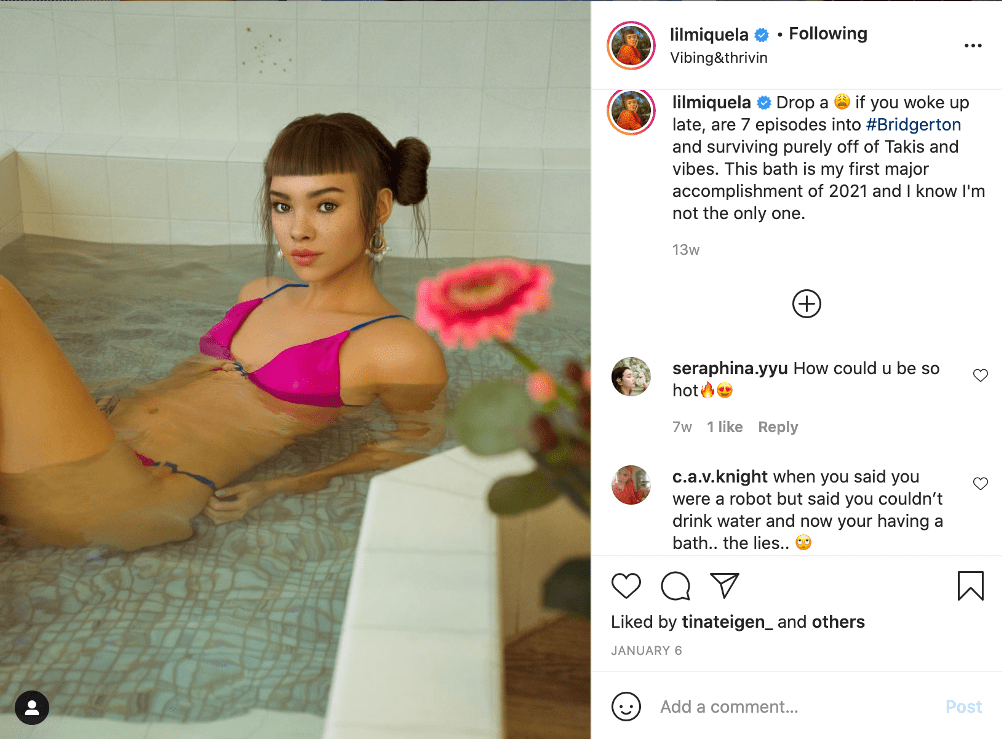

However, her presentation and marketing makes this hard to believe. Lil Miquela’s CGI body often poses in a way that caters Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze in a ‘traditional exhibitionistic role’ (Mulvey 1989:19). Objectification is common for instagram influencers, ‘She attracts the same fetishised gaze as anyone else selling her own image’ reflected in her comments section- ‘“so beautiful” one guy wrote on a post where a bit of cleavage can be detected, adding a drooling emoji’ (Petrarca 2018). We also have to question Lil Miquela’s agency. She is owned by a company whom chooses her appearance and posing and is treated like the ‘object’ Mulvey describes by being placed in ways which appeal to her audience (Figure 9).

Lil Miquela is used as a model to make money though Instagram promotions- she sits between being an advocate for change or a performative activist for profit. Russel questions ‘can a corporate avatar- in essence, a privatised body, symbolic in form- be an authentic advocate… towards social change?’ (Russel 2021:93).

In conclusion, Lil Miquela is the ideal ‘anti-body’ (2020:93) to challenge the gaze, but her lack of agency and use as a feminine object for commercial purposes stunts this. Even so, the rise of virtual influencers may open opportunities for feminist discussion for other creators, further pushing the idea of Russel’s ‘anti-body’ (2020:93).

References

- BORDO, Susan. 2015. It’s Not the Same for Women. [online] Chronicle. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/its-not-the-same-for-women/?bc_nonce=mingzypc3cezpb8al9z8xc&cid=reg_wall_signup [Accessed 15 March 2021].

- CADOGAN Dominic and ALEMORU Kemi. 2018. Are CGI models taking jobs away from real people of colour?. Dazed [online]. Available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/39654/1/is-lil-miquela-real-cgi-instagram-influencers-shudu-fashion-industry-racism [Accessed 15 March 2021].

- CHAUDHURI, Shohini. 2006. Feminist Film Theorists : Laura Mulvey, Kaja Silverman, Teresa de Lauretis, Barbara Creed London: Routledge.

- The Chronicle. 2015. The Male Gaze in Retrospect. [online] Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/package/the-male-gaze-in-retrospect/ [Accessed 5 March 2021].

- JACKSON, Lauren. 2018. Shudu Gram Is a White Man’s Digital Projection of Real-Life Black Womanhood. The New Yorker [online]. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/shudu-gram-is-a-white-mans-digital-projection-of-real-life-black-womanhood [Accessed 18 March 2021].

- MEAGHER, Michelle. 2002. ‘Would the Real Cindy Sherman Please Stand Up? Encounters Between Cindy Sherman and Feminist Art Theory’. Women (Oxford, England) 13(1), 18–36.

- MULVEY, Laura. 1989. Visual and Other Pleasures. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- MULVEY, Laura (1975) ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ in HALL, S. & EVANS, J. (2003) The Visual Culture Reader London, Sage

- PETRARCA, Emilia. 2018. Lil Miquela’s Body Con Job. The Cut [online]. Available at: https://www.thecut.com/2018/05/lil-miquela-digital-avatar-instagram-influencer.html [Accessed 16 March 2021].

- RUSSEL, Legacy. 2020. Glitch Feminism. London: Verso

- SCHROEDER, Jonathan (1998) ‘Consuming Representation: A Visual Approach to Consumer Research’ in STERN, B. (1998) Representing Consumers: Voices, Views and Visions London, Routledge

- WHITEWAY, Emily. 2017. Real Man, Real Issue: How Is an Unrealistic Representation of the Perfect Aesthetic, Leading to an Increase in Male Body Anxiety, Dictated by the Media and Fashion Industry? Dissertation (BA Fashion Design), Falmouth University, 2017