‘Seeing’ the Stigma?

By Tove Hellesvik (4th january 2020)

Defining mental health will continue to be dynamic and fluid and will grow and change as context and cultural influences change (Goldie, 2010 p.36)

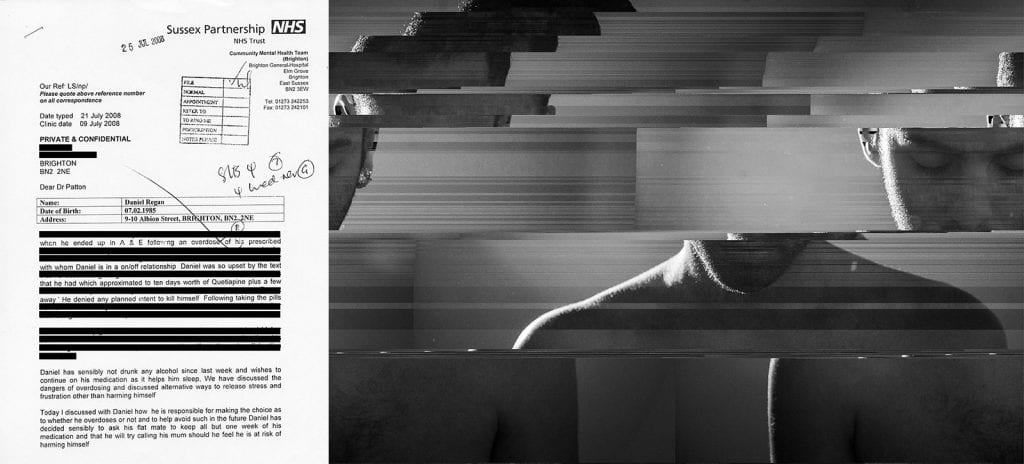

‘Seeing these observations of myself from an outsider’s viewpoint prompted me to revisit those times in my life through my own visual archive. I have always turned to photography to express the feelings of a fragmented identity, of my mind splitting apart and into something destructive, something unknown. Working with self-portraits taken on or close to the date of the medical record I have disrupted the image by digitally inserting those texts that are too personal for the public into the photographic image. The result is a corrupted portrait of the broken self, a metaphor for the shattered identity’ (Daniel Regan, 2015)

Defining mental health will continue to be dynamic and fluid and will grow and change as context and cultural influences change. These statements interact directly with the line of thought and questioning here. They provide an opening and understanding to the ideas of what mental health is, to explore the means by which photographers might capture the essence of that in photographs.

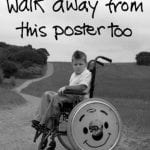

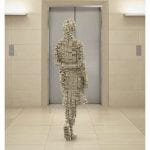

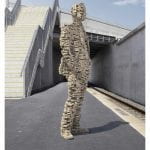

One thing is immediately apparent in much of this practice. A sense of invisibility, or of retreating from the world; both visually and physically.

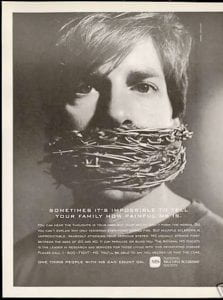

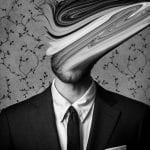

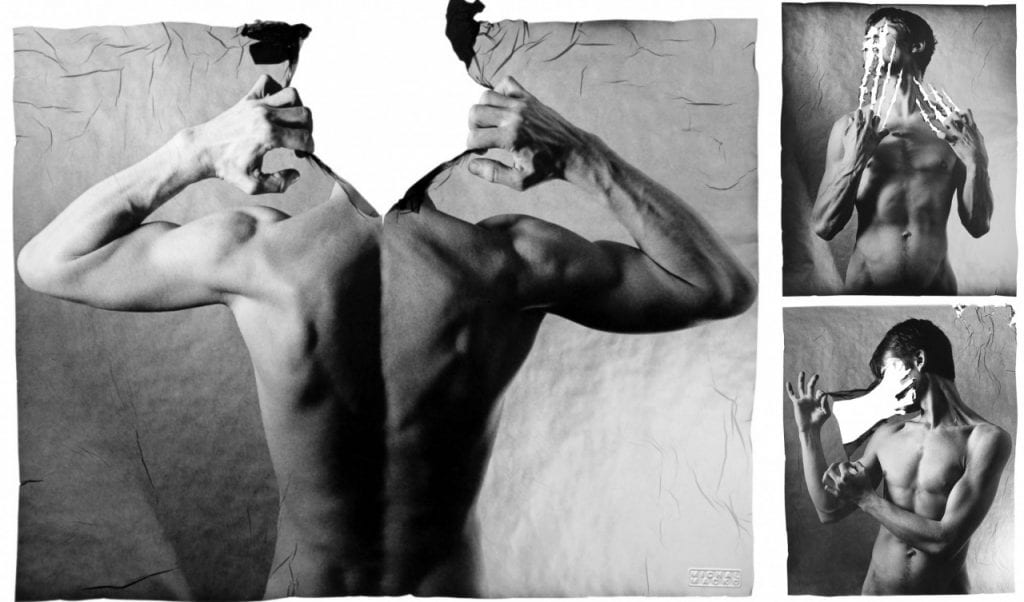

Rather than acting as portraits, they are transformed into metaphors. One can easily feel the sense of suffocation, of panic, anxiety and claustrophobia providing our first look at photographs bringing attention to the daily struggles of people with mental illness. Similarly, Michal Macků developed his own artistic technique to best tell stories through his photography. Calling it ‘gellage’ he moves the gelatinous emulsion around on film negatives and alters their appearance in dramatic ways. In these images, the subject seemingly rips himself apart, not unlike the feelings that depression and anxiety can bring.

However, with panic, anxiety and claustrophobia also comes despair, depression and the feeling of being alone.

The darkness which surrounds Alex Bland’s man in a box in Fragile (2015) shows an abyss that one can be pushed into and feared, or, find a sense of comfort for escape. As Goldie (2010, p.36) points out, we are essentially social beings and mental health can be socially created and socially destroyed. In which case, the push into an abyss can be confirmed as a social behaviour or result thereof. It is important to note, that mental illnesses can easily stem from forced social hardships, behaviours, abuse which we should all be mindful of when interacting with other people. A similarly metaphorical approach is to be found Liz Osban‘s practice, a photographer who went through depression and used her images to show this. She secluded herself into unfamiliarity and deserted spaces that were blue and gloomy. She beautifully shows mental illness in her works which evoke a sense of empathy from an audience, immediately relating back to creating an understanding space for the normalization of mental illness in public.

‘The dormant bodies create a sense of melancholy serenity, matched by scenery that is fixed, purgatorial. Wind-swept hair, paper planes, birds in flight and floating balloons act as an unsettling precedent for figurative journeys: the animation, it would seem, is projected outwards by the thoughts, fears and hopes of the individual, left unresolved and trapped within their sedentary vignettes’ (Aesthetica, 2015)

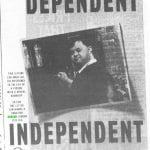

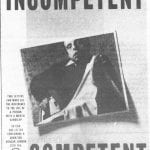

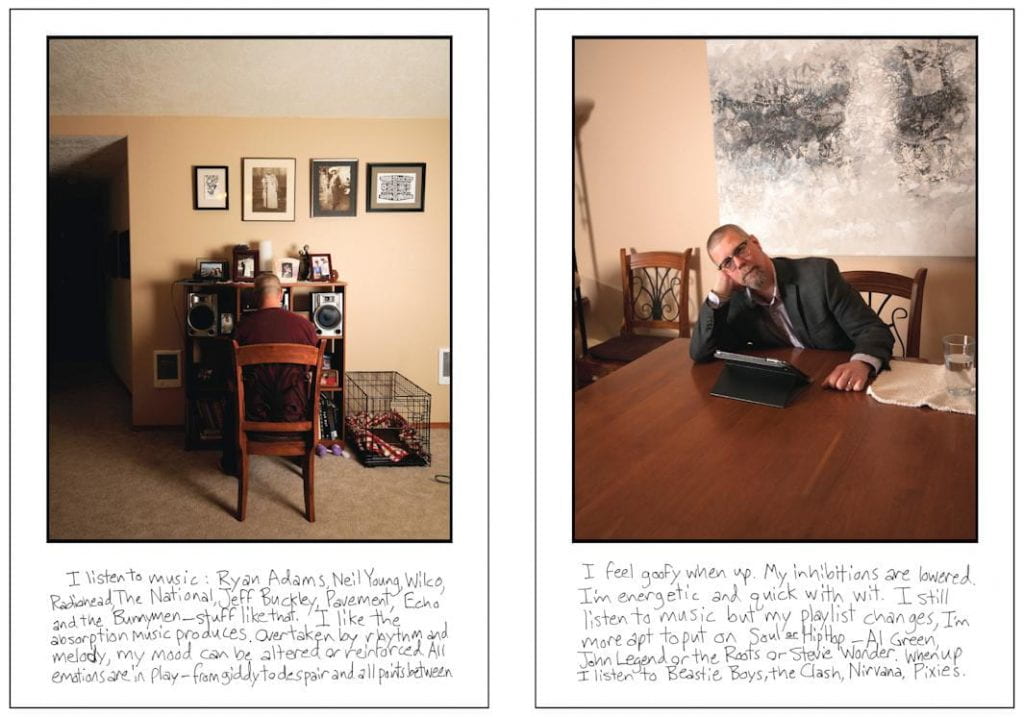

Goffman argues that the stigma of mental illness, is usually considered to be an undesirable attribute in terms of social normality. But what is social normality when it comes to mental illness? It is understanding that mental illness is an invisible threat that surrounds us all and to be more accepting when it comes to opening up about the struggles of life. Liz Osbert‘s project Dualities goes a long way in terms of normalising this by exploring people in their homes living their ordinary lives. She shows the different moods associated with daily routines. It provides insight on ways that mental illness can have different effects in different ways. It is not always a continuous moment or feeling, but rather a series of good and bad days. The everyday aspect of ordinary people helps normalize societies views of mental illness.

‘It opens the door for more artists to make work about their personal experiences and share it with a wider audience. Since photography is a relatively democratic and accessible medium, now it means that there are greater opportunities for people to explore photography as a medium to process, document, and conceptualise inner states in a therapeutic manner’ (Regan in Campbell, 2019)

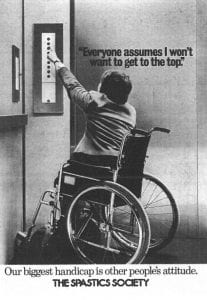

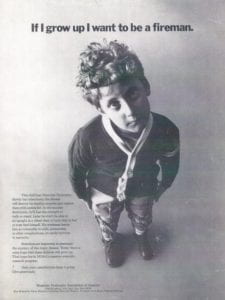

Society can be a cruel place for mental illnesses and healthy lifestyles. Sean Mundy‘s Nescience illustrates a dead body amidst hurrying strangers. No one taking a glance or slightly curious with the scene before them. Everyone is so caught up in their own path that they forget to notice when someone is in dire need of help. The stigma and discrimination faced by people with a mental illness is widespread and offers a key public health challenge to stereotypical society views. (Goldie, 2010, p.215). Photography offers us an important gateway to challenge and change these stigmas.

Further Resources

- Tara Campbell (2019) ‘Exploring Mental Health Through Photography’ in Creative Review

- Kate Hodal (2019) ‘Without Photography I Wouldn’t Be Here‘ in The Guardian, 20th July 2019

- Anna McNay (2015) ‘A Snapshot of the Mind‘ in Photoworks

- Daniel Regan (2019) Fragmentary.org

- Tara Wray (2018) The Too Tired Project

- Time to Change (2017) Get the Picture Project