Human Bodies not Human Beings

By Abigail Emm (22nd December 2019)

‘A society where feminine beauty is defined not by the human self on genuine intellectual and sentimental grounds, but by a computer software on the grounds of economic interest, is more dead than alive. It is a society of human bodies, not human beings’ (Naskar, 2017)

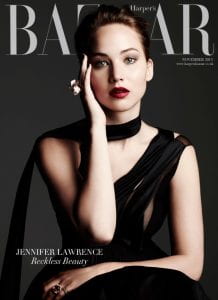

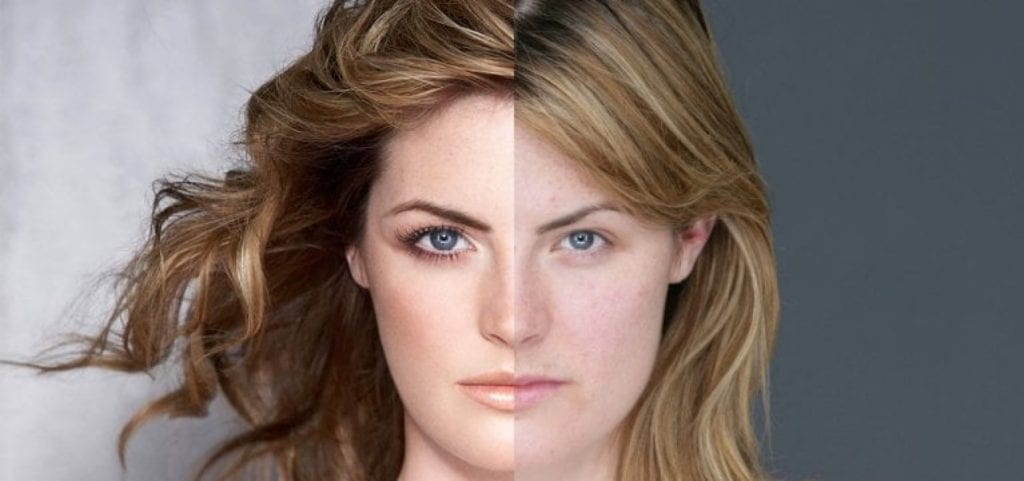

When we really consider the all too ubiquitous digital retouching / altering of models’ appearances, such as the removal of blemishes and changing of body shapes, we must also think about whether this is merely to aid the sale of an item, or promote a beauty ‘standard’. Or both? In our image world, these types of images are more easy to come across than ever, with a combination of social media, magazines, billboards and advertisements, the exposure to these types of representations of ‘woman’ are nearly inescapable.

Does this create unattainable expectations for bodies / create a market for products and services that could aid an individual to get closer to a so called feminine ‘ideal’. What is the morality of retouching models? How does it effect those who view these images? Is this ‘ideal’ a myth in itself?

A study by Kleemans et al (2016) on the impact of manipulated / perfected Instagram images on young women, concluded that indeed, manipulated images were more favourably viewed than their un-manipulated counterparts. Interestingly, the participants in the study also struggled to detect when the model’s body had been slimmed down. This causes concern, as this lack of awareness might suggest that there is a culture of doctored images as ‘reality’, and that young women may start comparing their body to these fictitious myths.

‘Exposure to manipulated Instagram photos directly led to lower body image’ (Kleemans et al, 2016)

Bingham (2015) writing in The Telegraph reported that 90% of teenage girls ‘digitally enhance’ photographs of themselves before posting them online (Bingham, 2015). I believe this statistic wouldn’t be as high if this ubiquitous (but all to often hidden) use of retouching was lessened. In allowing young women to see other women with thier true blemishes and larger stomachs and thighs, a healthier body image will be developed, as the pull to change their bodies to resemble the (published) ‘myth’ of the model is made more realistic.

‘Retouching or otherwise altering pictures, to make them appear thinner, for example, has become the “new normal” for young people’

(Bingham, 2015)

This is clearly a dangerous game, particularly if young woman perceive these doctored images as ‘reality’, and as a result start comparing their body to fictitious ones, which can lead to the development of poor self-esteem and eating disorders. As Sarah Marsh (2019) proposes, ‘There has been a dramatic rise in hospital admissions for potentially life-threatening eating disorders in the last year, prompting concern from experts about a growing crisis of young people experiencing anorexia and bulimia’ (Marsh, 2019).

Is this directly related to a ‘myth’ of an ‘ideal’ woman / an ‘ideal’ body?

In 2006, Dove created an advert that depicted a woman preparing for a photoshoot, and subsequently being heavily photoshopped; with her neck lengthened and her eyes enlarged. Whilst this advertisement was praised for highlighting how drastically retouching can change appearances, it was also condemned, due to the company using it as a marketing tool. Dove were also selling ‘Intensive Firming Cream’ at the time (Traister, 2005) which aimed to improve the appearance of cellulite. This created a contradiction in what the company were saying vs thier simultaneous financiaal gain, which, when it came down to it, was still profiting from telling women that they needed to change their bodies.

Companies are slowly starting to alter their models less, which is shown through multiple fashion retailers such as H&M and Missguided halting their use of this practice. This encourages people who are concerned about the ethics of retouching to shop at these stores also. Whilst this is a step in the right direction, more companies need to join these retailers on their body-positive advertisements to make a larger impact

Follow Abigail Emm on instagram