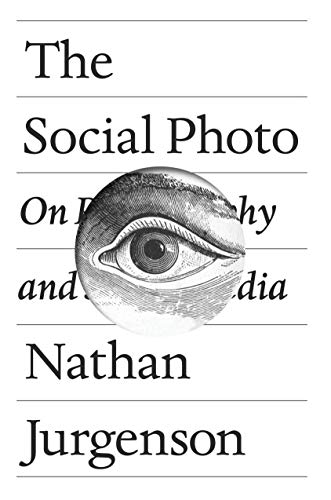

Nathan Jurgenson

Edited & Compiled by Tracey Paddison (5th January 2022)

TP: You don’t consider yourself a photographer, however you are bringing photography into the ‘real world’ where is where certainly it exists today – something you discuss as ‘digital dualism’. The tone of your book is wonderfully celebratory about photography, rather than being perhaps more pessimistic about living in a contemporary image world (to allude to Sontag’s writing in On Photography for example).

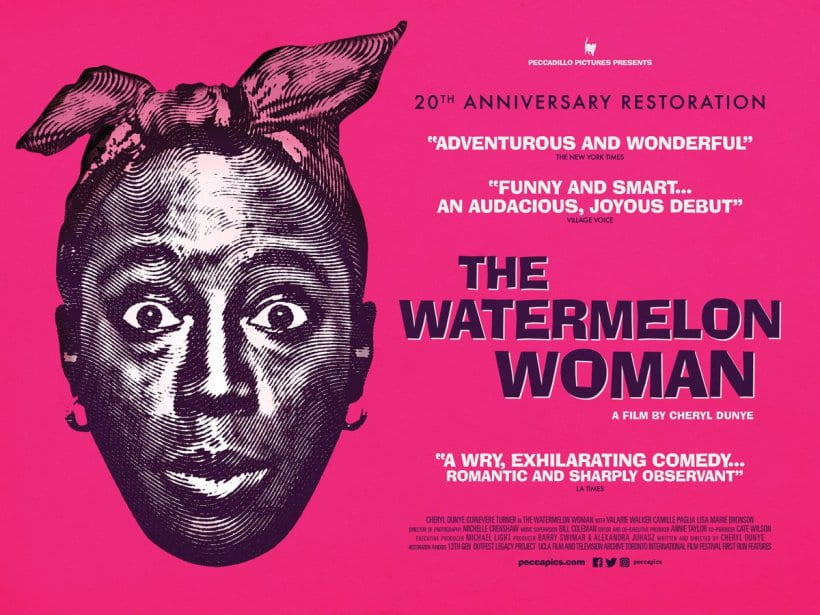

NJ: I think that ties in pretty close to the sort of positivity in the book relative to some other photobooks, as well. My background is not in photography; it’s in Social Theory and you can probably tell that from the people I’m citing throughout the book – so I’m a bit of a tourist in the photography world or the art world and so that’s been interesting how many book talks I’ve got to do at galleries and museums. A lot of my book is written as a critique of all the other books you can read on photography because so few of them could even touch on what’s happening with say, Instagram or Snapchat. So I thought there was a real gap there, and if you wanted to pick up a book on photography, really the only thing you could read about was art photography, professional photography, photojournalism, art or professional uses of photography. But of course, the vast majority of images being taken today have nothing to do with the rule of thirds, or what’s appropriate to run on the front page of an newspaper – so I wanted to write something that was taking on the vast majority of images being taken today.

So I do allude to this idea of a dichotomy, although it’s a somewhat loose one, between traditional photography and social photography. I offer a few different definitions throughout the book about the sort of ‘objectness’ of traditional photography, how it strives to convey information or make an artistic aim, but in any case it’s the ‘image object’ that’s really central – whereas in the ‘social object’ – the image object fades away because I define social photography as much more like speaking. It’s a discursive act much more than an informational or artistic act and in that way a social photo can disappear,

I mean on Snapchat literally, there could be a timer that self-deletes in the same way that when you’re talking to somebody you may not always record what you’re saying if you’re hanging out with your friend you’re probably not putting on a recorder and recording everything. That’s the perspective that I wanted to write about – all these images that people are taking who don’t consider themselves photographers – the vast majority of images taken today are not taken by someone who sees themselves as in the medium of photography ‘proper’ and so I think part of the positivity is because I think it’s really important to look at how people are talking today just the everyday-ness of taking images, how you communicate with your friends and family. To me as a sociologist, that’s extremely important. I think in the photo world a lot of the photo theorists, when you pick up books about photography in a book store, it’s not just everyday people talking to each other with pictures. Whereas, as a sociologist, that’s what you study, you study how people behave, so it gave me a different perspective – I think I’m inherently interested in how people are talking to each other, so therefore I’m inherently interested in the very mundane every day photos that people have on their phone cameras. I think that’s where the positivity comes from.

When I first started writing the book, there were a lot of discussions like, why are people taking pictures of their lunch, that’s such a boring and stupid photo and it’s not a great ‘art’ photograph, It didn’t’ obey all the rules that you might want in an ‘art’ photograph, but you may have sent it to your friend who because you both went to that same restaurant a year ago and you were reminiscing about that. It’s a social good, not an artistic good. The question is not ‘Did it obey the rule of thirds’? The questions are ‘Were you smart, were you funny, were you creative, did you respect the other persons privacy in the photos’?. It’s these social questions and those are things I try to look at in what I call the social photo.

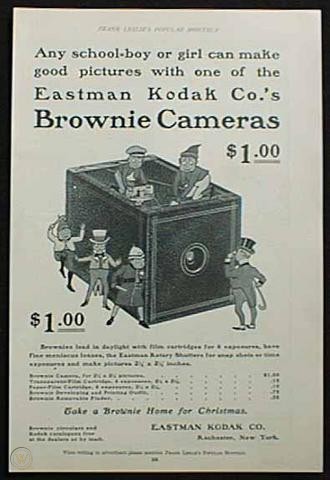

We can maybe have some fun thinking about how photography was more or less social in the past, surely the Kodak Brownie camera; shipping a photo album with the camera, that you would then want to fill up. That seemed more social a photographic act than it was before. Or the Polaroid camera in the 1970’s where the camera was like a toy and you could just pass it around – and you’re take a picture and just hand it to somebody – and sometimes those were kind of ephemeral. And of course, today people take images with digital cameras all the time. I’m trying to discuss the impulses behind taking and sharing those photos. Another thinker who is very important to me is Danah Boyd who writes a lot about social media, and I think she’s provided a very good model of how to be critical of these technologies yet still extend empathy to the everyday uses of it, into the users.

TP: Do you think the ‘Kodak Moment’ helped photography become a truly democratic medium? What do you think really makes that difference between ‘art’ photography and ‘social’ photography, Is it context / subject matter, for example?

NJ: I’m rejecting the ‘art’ framework of it, I see photography as something that we’re learning to speak with, we’re learning to talk with images – but I think talking and speaking with images is merely something that is something for an elite few. The title of the book already assumes that and the reason for that is that once you connect a camera to the internet. I remember having a digital camera, but I wasn’t taking pictures all day with it, you wouldn’t take a picture of your Latte – you’d have no reason to even when you had a small digital camera. It could fit in your pocket; you could take as many pictures as you want basically for free – and you still didn’t take that picture. The key difference was once you had an audience, and once you make a picture of something you can communicate with very easily, suddenly that Latte changes.

Whereas before, I would have to figure out a very interesting picture of my Latte; I’m probably not going to think of one ‘properly’; it has no informational content at all. Nobody needs to know what my Latte looks like. It has very low information news quality to it – but once you add a internet connection to the camera, it turns the Latte into a symbol; it turns it into a linguistic element, where now it’s not just that particular latte, it’s what does the Latte symbolise for myself and the person that I’m sending that image to. I could send that picture to a friend who would know that what that’s means is that I’m tired, or that I’m at a café, it meant that I was working or it meant ‘maybe you should come by the café’ or it could mean if I’m having a relaxing morning. But essentially the Latte is now no longer a just a Latte – it’s a symbol.

You know, here in Los Angeles, we have lots of palm trees and I mention the palm tree in the book. It’s always the first example I think of, I will take a picture of that palm tree, but if I’m taking that picture a lot, I’ll use a palm tree emoji intead. It’s a symbol, what does that palm tree stand for, a ‘palm tree-ness’? I don’t want you to think what a great photo I took of that palm tree, I don’t want you to look at the exact detail of that palm tree, I want you to think what does that palm tree mean. It means ‘the weather is nice / I’m on vacation’ – they are symbolic messages and I believe that’s what is the very democratic everyday aspect of social photography. Namely, looking at the world through its symbolic potential and how I can ‘speak’ with things in their visual form, almost like the social camera turns the whole world into emojis, and you can speak with them symbolically and so I think that’s the big difference.

TP: It almost sounds like you’re making a semiotic analysis at this point?

NJ: Yeah, I was very careful not to say that word. If you take a linguistics class, the linguistics people have very strict rules about what counts as a language, and there are very important distinctions between all of these things. But it’s absolutely right, it’s a semiotic, discursive analysis and so isn’t it weird that a lot of the photography books in the book store don’t tackle that in a social sense, they want to talk about ‘art’ or journalism and things like that and so it’s important to make these sorts of analyses about the vast majority of pictures taken today.

TP: You make a beautiful analogy in your (2019) talk at The Photographer’s Gallery – saying that if aliens came down from outer space that they might think that we had an extra eye that lived in our pocket (our mobile phones) – that we chose to bring out from time to time – and that we can look at the world through this eye. I wondered if you could expand on that a little bit?

NJ: I think that is one of my guiding ideas when I think about social photography. Let’s think – you’re at a concert and everyone’s got their phones up getting a picture or whatever. I was thinking about an alien anthropologist who lands on Earth from another world, what it would seem like is that we have a removable eye that lives in our pockets or in our hands and that we can speak with that eye. It’s an eye that talks, what it sees can be communicated to other people’s eyes. It really follows the embodied way I think of photography and really, all technology, as something that’s really these sort of fleshy appendages we have – they’re not these cold mechanical things that you can put away and you know you’re suddenly away from. Technology’s always a part of the way that we see the world and this changes with the technology we have. It’s always something that’s in us.

I never like to make too strict of a distinction between the human and the technological, it’s very much merged. That’s why I see smart cameras as these eyes that can talk, they’re part of how we see the world. I think an alien would assume that; they would assume that these things are just a sensory organ that we have – the important thing is that they act as if they were a sensory organ and they do change the way we see the world now that you can take a picture – and send that picture to somebody else. It changes the way you see the world, even when you have the camera put away, you still see the world through this idea of a potential photograph, you can see who you would probably send it to or if you’re thinking about Instagram you’re thinking ‘I know that this one would get a lot of likes’ and you have all of that intuition, it’s all part of how you see the world and that’s true of pre- digital technologies as well so it’s not like something that just came around.

TP: What’s your feeling on how people react to social media and if you think about Instagram as an example or Facebook for that matter, where people take great interest in the quantifiable number of likes the number of comments they get. In the UK, there have been quite a few articles in the media about how it affects people’s mental health, particularly amongst young people.

NJ: That’s one of the things about social media I’ve always disliked the most, and I think it’s something we could have easily gotten away from. Imagine you’re hanging out at the pub; you’re talking with your friend and everyone else there got to put a number on every single sentence you said with your friend and then everything was being scored. You would probably start to change the way you talk, I would. I bet you’re going to have a really crappy conversation with your friend, which is exactly why every conversation on Twitter also is really bad, right? because you gamified it. Anything with a score on it is a game right?

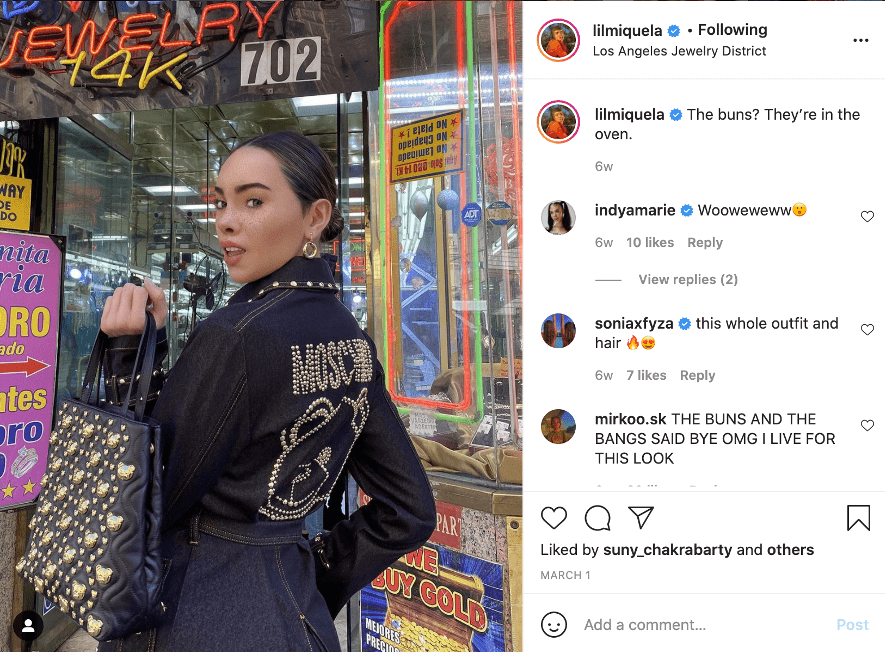

I think the thing about metrics when companies first put a metric on a thing, a score; the metric is not measuring how good the content is – so you have content and then the number comes around later and says the content is good or bad. What happens is people change the content they post to make the number big, so the number is actually preceding the content. The number isn’t a measure, it creates it and I think that very true within photography and social photography. We all know the style of Instagram, that is created by the metrics and by the numbers and scores and so I think that really just sort of flips the means and the ends; the metrics at best are just the means to get to something that you want to see but what ends up happening is the metrics become a end.

When I was first writing about social media I was drawing on Georg Simmel, another social media theorist from a hundred years ago who wrote a similar same thing in the book The Philosophy of Money. He discussed how money went from being a means, ‘I want money so I can buy stuff’ to being its own end, where people want to accumulate money just for the sake of having money. It seemed to me this idea was a metaphor for what was happening on social media. So, 10 years ago when I was writing pieces arguing that we should get rid of metrics on social media, it’s only been within the last couple of years where I feel like finally, the companies are starting to see how much people don’t’ like using social media precisely because of the numbers and the metrics.

There’s an artist named Ben Grosser who has a Twitter demetricator and a Facebook demetricator (like an extension you can add on so you can’t see the metrics). I think all these platforms would be greatly improved by not having the metrics. It’s the same bad incentive – the reason Cable News in the United States is really bad, right? Because they’re chasing ratings – when you link quantified attention with the content you produce to get whatever ends you want, more followers, more money from advertisers, it creates really bad incentives. I think things would be much better if you could de-link those incentives and not have those metrics.

TP: I’m really interested in your thoughts about the FBI using photographs that people had taken of the storming of the Capitol building, what’s your take on that?

NY: I was very interested in the news stories that came out of the January 6th 2021 Capitol riot incident and I thought they were telling with how we talk about selfies in general. Obviously a lot of the people that went in there, were there with costumes, they’re inside the Capitol – of course they’re going to take selfies, that’s a part of pretty much anything people do today. But it was interesting how many news stories came out that I think made two big mistakes when they pointed out that people were taking selfies.

First, the word selfie, has this trivial connotative meaning – that they are they’re just there for the pictures and this is the mistake I think people make a lot when somebody takes a picture. The assumption is that they’re only there for the picture and that somehow their experience in reality is ‘less than’ ie that it’s completely performative, it’s completely staged. People take pictures of their food instead of eating it and it’s in such bad faith, I’ve taken pictures of my food all the time, it’s never once changed the flavour of the food ever.

So here’s the two mistakes that I saw with people talking about the selfies at the Capitol. One, is to trivialise it, to say that those people weren’t political, they didn’t have political aims – they were just there for the content and I think that was very untrue. They were real, with very bad regressive political aims and they were real, just because they took pictures doesn’t mean we can then dismiss them as not a political or non political actors. I think you still need to discuss their politics and critique them, in my opinion.

The second mistake was to say to downplay the violence that happened there. The same people who took selfies were also there, seemingly ready and willing to hurt other people and the idea of it wasn’t a big deal, they were just there to take pictures. I think is very wrong. You can both dress up in a funny costume, take selfies, and have strong regressive political politics and be willing to be violent and you know, people did get hurt and there was violence, there was intentions for even more violence than even happened.

So let’s remember that just because someone takes a selfie doesn’t doesn’t mean they are political actors but then, just draw that back to just why is it the case that the word ‘selfie’ removes all the importance from an event or a person. Why do we use the word selfie to see somebody as a purely performative actor; as somebody who is not really experiencing the moment. Why do we use cameras and photography and selfies to really mean less than real, to mean less than important. That’s what a lot of the 2nd half of my book discusses. Why do we think that photography and technology is inherently less real or moves people from the real moment and things like that? I find those questions and those assumptions really fascinating,

TP: You talk in the book about social photos aren’t taken as a document that you’re going to put in the family album and go back to, it’s not a historical record, it’s about showing your life and having a conversation about your life now and something that’s looking forward. What are your thoughts on whether that perception of the social photo as not being a document that has any historical value, Is it just an ephemeral thing? Is that perception so ingrained that the people that were involved in the Capitol riots didn’t really consider those images that they were taking, didn’t consider them as documents or records that would be kept and then used to prove that they were committing crimes or whatever, They didn’t see them as artefacts that people might go back to – it was just a very ‘in the moment’ thing is that an example of or evidence that this kind of perception of what social photo is – that it’s just language that’s being used in the moment.

NJ: That’s a great question. I think there was probably lots of different motivations. There was lots of different kinds of photos taken that day by different people with different motivations, and there’s probably a nice spectrum there that I think you’re sort

of laying out. You could probably, the guy that is in the horns and he’s standing on the at the lectern, and he’s asking people, ‘hey, can you take a picture’? Can you take a picture? Find somebody with a really good camera, ok and you get my picture. He knows that this is this his moment, he wants this picture forever, this is one that’s probably going into an album.

As well, there were other people who were somewhat surprised that they were making their way into the Capitol and they have their phone up going like ‘look where I’m at, this is wacky’. You can almost take them, lay them out, and probably do an analysis on that. This reflects your point also on the FBI data collection, there’s a lot of data collected with each one of those images and you could basically trace all these people. You know these people have phones in their pockets that are connect with SIM cards, every one of their movements was easily traceable – so I kind of make a point in the book that when I talk about social photography being more about the expression than the information. I think what you bring up is a really good corrective reminder from the perspective of the users, you switch the perspective to that of the law agency and the whole thesis ends up flipping, which is another book that could easily be written and it’s something that you know is a shortcoming of my book is that’s really not my focus and somebody else could completely focus on that would be a very good book.

TP: It seems to me that it’s social media, as you’ve pointed out, that’s the catalyst as to what’s changed. If you look at it purely from a photographic perspective, it doesn’t occur to me that there’s anything really that distinctly different about photographs before social media and after social media in general terms. People took family photos on their vacations, not meant for serious or ‘artistic’ purposes, they were just memento’s. Do you see that sort of evolution from this explosion of image world and lots of different perspectives through social media and where is it going?

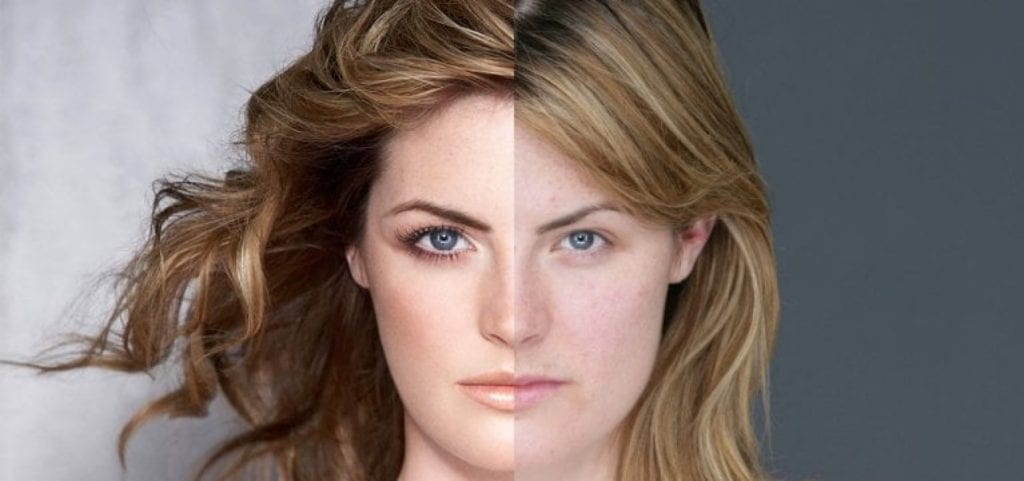

NJ: That’s a good question and I like the historical analysis of thinking about like image saturated culture. What is interesting is you go through history is that at every single stage in history, people made the point that this is an image saturated culture. The world is speeding up, there’s too much information and images are taking over and so people were arguing that in the 1890’s, in the 1920’s, in the 1950’s, and the 1970’s. It almost comes in waves. As we get older, we see the pace of the world as too fast but when you look at the world from before we were born – it was too slow. It’s hard for me to really think about images saturating the world more, or the world speeding up more because the acceleration is so even and steady that it’s when everything is accelerating all the time. I was thinking about one of the critiques of social photography is that, photography has lost its relationship to the truth. We don’t see pictures as true anymore and people talk about deep fakes and all these things. What are these new technologies and image making and deep fakes gets a lot of time and this is true. It’s very easy to fake photos today. One of the big differences is augmented reality; when I take a picture of my face I could do lots of things with that, I could have puppy ears. We augment photos a lot more and I think that’s going to be a very important change in the way that photography looks; a sort of everyday manipulation of the images but I don’t necessarily see that as photography losing its relationship to the truth.

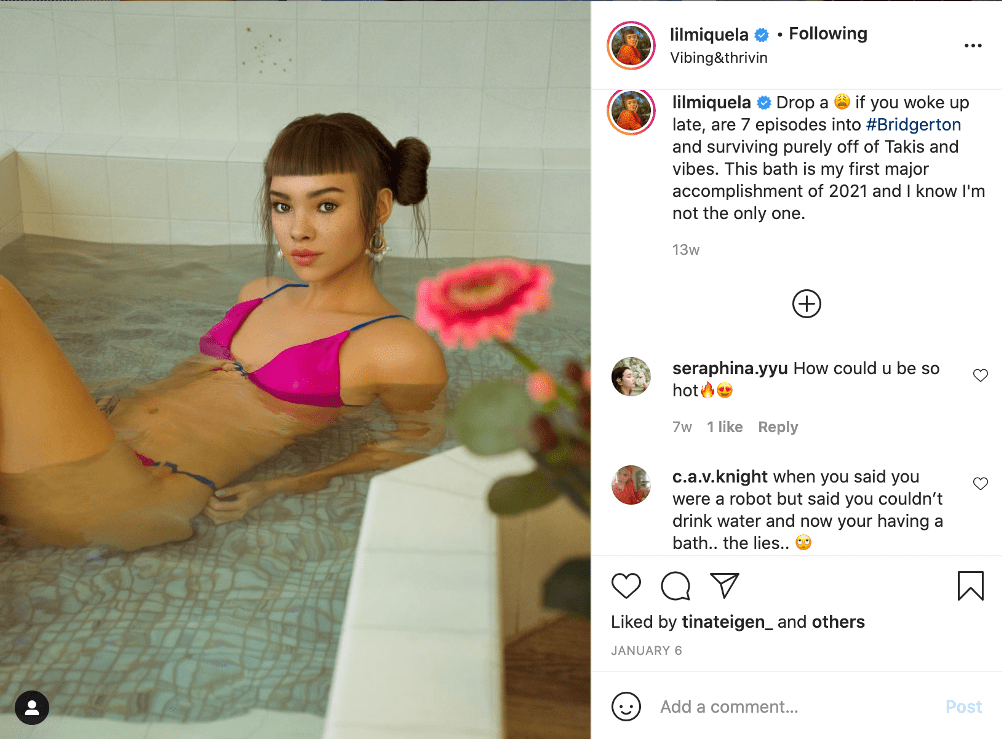

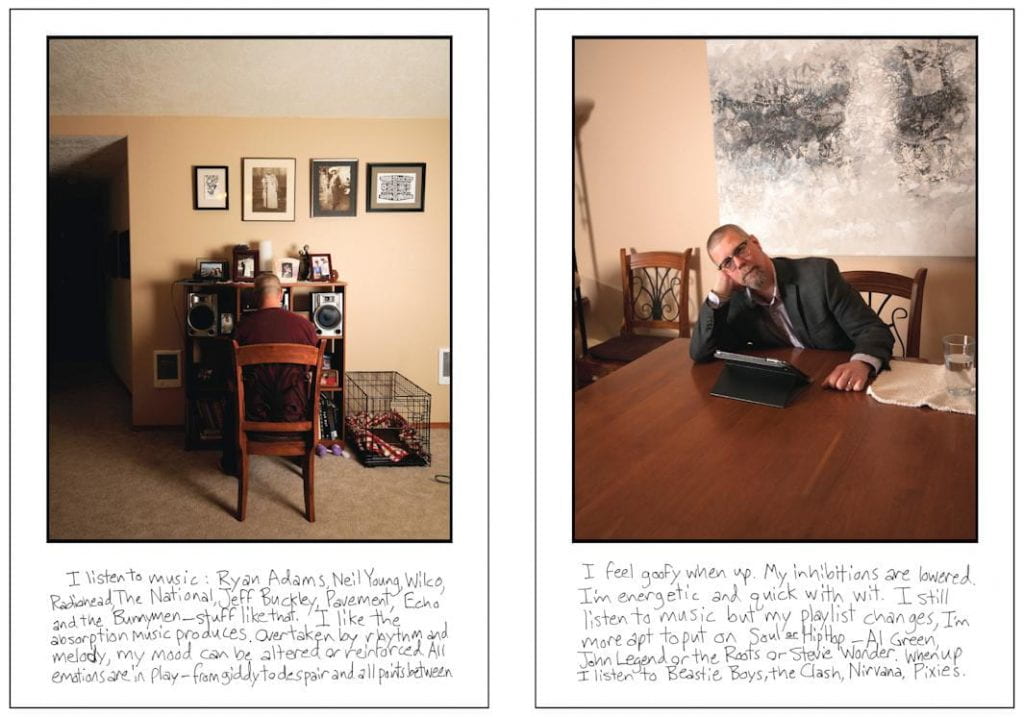

If I take a self portrait (which I see as different from a selfie), I really want to focus on what my face looks like in all of its nooks and crannies. It’s an informational object, an artistic object. Selfies are usually more, ‘this is how I’m feeling / what I’m doing’ and I think sometimes adding the augmented reality to your photo as you perform yourself, can actually can be more true. Like, this is how I’m feeling, this is how I express myself, this is how I want to perform’ – as you see a lot on TikTok, a lot of times those performances reveal who I really am, a lot more than like a really good portrait that says this is exactly what my skin looks like. I’m not just my skin. I’m also the performance of myself. I think a lot of what we do with editing photos with augmented reality lies in the performance,

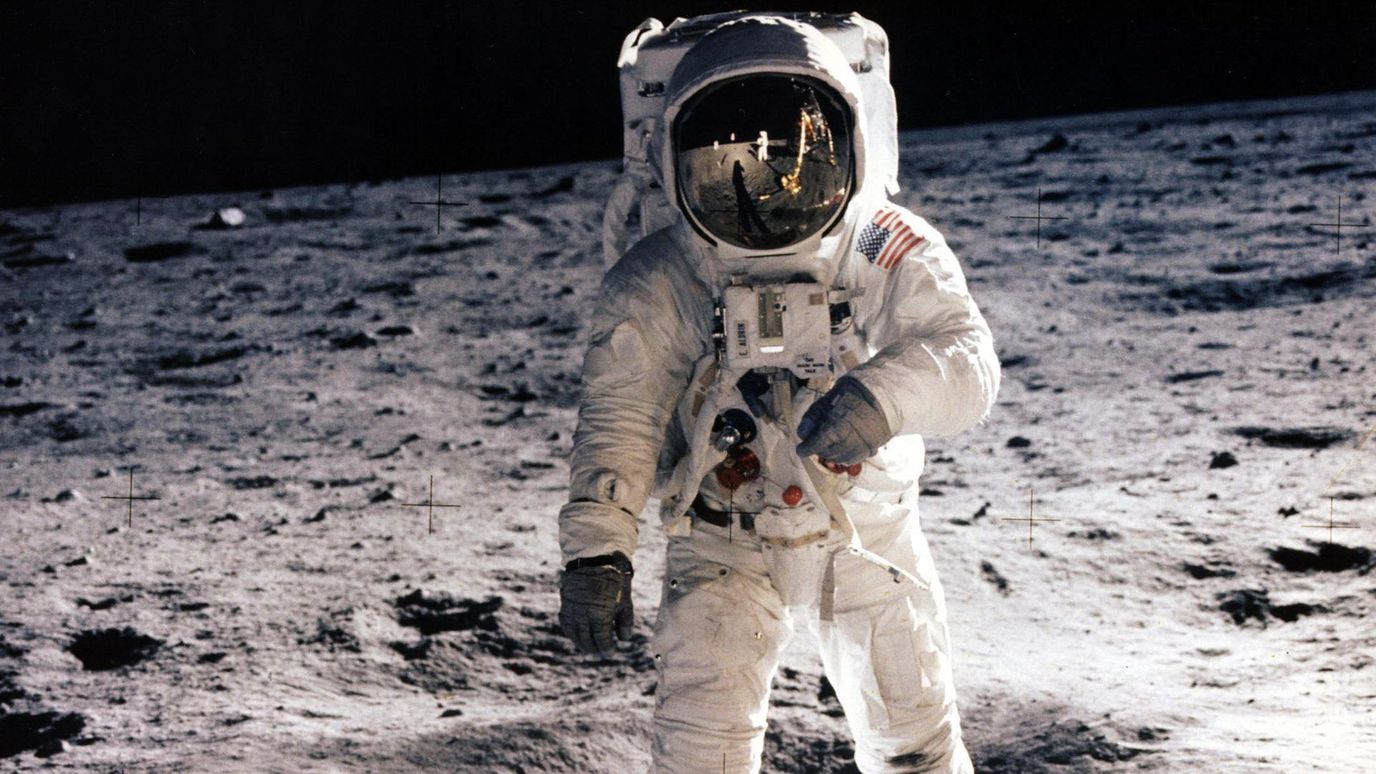

I think that is a lot to do with conveying different kinds of truths of who you are more than just perfect visual depiction and to make one more point on that, just in general, is get away from the selfie to news photographs. You know, we had a really bad shooting in the United States, we have a lot of them, one of the worst ones, what happened in Las Vegas a few years ago, where there was a man who was at the top of a hotel and there’s a concert below and he just started shooting into the crowd. There was many images taken as people were running, people were taking photos and videos and uploading those and so basically what you had was an event that you saw from hundreds of different perspectives, all at once. No one doubted that event happened, but right now there’s a conspiracy for everything. People have conspiracies of who that guy was and what his motives were. Nobody doubts that event happened because it would be almost impossible to get every single one of those people to fake their photograph in the same way, right?

That would be just having the very technology that makes it very easy to manipulate one image or one video, also makes it almost impossible to fake an event like that, because that same digital technology meant that everybody had a camera in their pocket and many people were taking videos and photos and so we actually had images and video that was more believable than, let’s say, the Zapruder film when John F Kennedy was shot, or people make lots of people debate about the moon landing, people debate about lots of photos and videos from the past and events can happen today where people actually debate the existence of it less. Now sometimes they debate even more, so I’m not saying , photography is now all true but I certainly don’t think photography has lost its bearing on truth. Which is I know is a far tangent from your original question, it’s just kind of the thing that it made me want to talk about, but just to sum up, I think augmented reality and photo image manipulation is just looking an act differently today than we did before.

TP: I’ll just go back to your comments regarding counting followers and counting people who would like your post – isn’t that really what the social photograph is about, isn’t that what social media is about because without the followers, without the kudos if you like, then there’s no point in putting it on there really, that’s really what people are looking for. For instance on Twitter there’s a guy called Piers Morgan, I don’t know if you know him, I think he was over your way for a while. He browbeats followers who disagree with him by saying ‘hang on I’ve got 7,000,000 followers, you’ve got 357, my argument is better than yours’. When Donald Trump was banned from Twitter their share price dropped. You know it’s why these companies exist in the first place. Another thing I’d like to point out is I think young people perhaps they are leaving social media, or are finding new social media platforms. So it’s becoming an older persons place and young people are moving on to the likes of TikTok, Clubhouse, things like that. So I just wonder what your opinion on that was as well. Sorry I rambled a bit.

NJ: No, I think you’re 100% correct. We have to use these words precisely when we use the term ‘social media’. Think of messaging apps and Clubhouse, Discord, even something like the game Fortnite – is this social media to the degree that people are playing it together and hanging out with each other and talking to each other? I don’t want to let Facebook and Twitter own the word ‘social’, as a sociologist that would be very scary A lot of my criticism (and I agree with you) is towards the kind of ‘public posting’ mentality, aspect, especially early social media, where you post to public / in public to everybody and you try to rack up as many points as possible. That was very popular and it also was very destructive. It still is very destructive in a lot of ways and a lot of people don’t like it, people don’t enjoy using those sort of competition style apps. Often times they are gamifying, sociality gamifying talking to your friends, gamifying having opinions, all those things can be fun it could also be really destructive.

But by far the vast majority (when I’m talking about social photography) the vast majority is happening through messaging. Some of it gets posted, you know Facebook, Twitter, kind of style, but the vast majority is, you take it and you send it to one person or a small group. I think that small, kind of more private, sociality is more what I’m thinking of usually then sort of just I’m posting in public Instagram hoping for likes.

TP: What are your observations of the role of social media during the pandemic, and a rise of online connectivity?

NJ: I mean obviously, I have some of the very boring and normal thoughts of this. This conversation probably wouldn’t happen outside of video conferencing at the same time I

am tired of and dislike video conferencing as much as everybody else. I think it, you know, sort of feels like email. It’s kind of a necessary evil, and maybe you’re not supposed to like it. Through the pandemic I typically work from home and so I’ve been able to stay home and I’m very fortunate in that sense. This answer would be completely different if we were talking about workers who were still out and about working but I think a lot of how I talk about technology in the book is that it really enables face-to-face conversation. I don’t see those things that separate. If you’re a more social person, you have more friends and you hang out and you do more things; you probably also talk to them using your screen as well, right? I think at best social media does that. It allows us to spend more time with people away from social media and again when I talk about social media, I don’t mean just Facebook and Twitter and Instagram. I also mean sort of all the messaging and smaller group activities that are more popular that people use their phones for.

During the pandemic that really shifted, that we are doing a lot more with our computers as a replacement for meeting in person and which is essential like it was, it’s a lifesaver. I’m imagining you know the 1918 pandemic and how lonely and isolated that would have felt without the Internet and so it’s great that it did that. I think that we’re used to social media, today it’s being used to replace offline hang out. I think social media is going to go back to being something that facilitates in person meetings rather than replaces it.

TP: What predictions you would have for things like the future of the social photo, how we behave as social photographers, how you see social media developing?

NJ: Unfortunately, sociologists are very hesitant to make predictions about the future, just in general we’re not the best futurists out there. I think you know technologists love to pontificate about the future and usually be wrong. I always think about Marshall McLuhan, he always said that the closest you’ll ever get to that is understanding the present. Even the best artist, the best futurist – all they’re really doing is understanding the present because everyone’s always living in the past and the best futurist is one who can actually understand what’s happening today, I tend to kind of follow that philosophy, so I think it’s really hard to make predictions about the future. But I think there’s a lot of things that people are doing today that are under scrutinised or under appreciated and I think that the main things that I think about are certainly augmented reality in the sense of anything in the world being something that you manipulate, that computation being applied to pretty much anything in the world, anything in the world becoming a symbol, anything in the world being something you can communicate with and I think that’s going to end up being very interesting in lots of ways that I can totally predict but that’s sort of where my mind is.

I really think the rise of game engines for things, especially at things that aren’t just gaming. I think it’s really important, I think I look at Fortnite or Roblox or something like that and and I really see those as social media, more than games. You know, sometimes the game is like the billiard table in the pub, you might go there to play but you’re mostly there to hang out with your friends. I think that is what we see a lot with gaming as well as how the sort of game engines are being applied to the everyday world, again that facilitate adding computation to everything. I know that’s really abstract and I don’t have a lot of really great examples of how that will play out but I think 3D modelling and game engines as they are applied to the world, as they become social spaces as the world, is sort of made computable as computation is played on to it.

TP: We’ve skimmed the capitalist elements of social media and social photography because obviously there are a lot of companies out there making lots of money from this as we well know. So surely, if we accept that social media influences individual behaviour as much as vice versa then presumably there must be a fair number of companies out there making predictions about how they would like to see people’s behaviour change over the next decade.

NJ: I think that’s absolutely right and you know, for people to behave in ways that are monetisable. Yes, that’s certainly a big part of it and it’s something my book doesn’t spend a lot of time on; the political economy of the image. If somebody writes that book, I’d almost recommend they read that book first and read mine later. I think is really important and that also brings up another another kind of futurism, maybe it’s utopianism, but would be through regulation of social media, enforcing better behaviours and practices. Europe is better at that than in the United States but can we envision social media products that don’t have a profit motive and something in the public domain that could be used by everybody that doesn’t have bad incentives. I don’t have a great answer for that, there’s certainly people who are working on that, trying to make platform cooperatives rather than companies, so to me, that would be a really fun answer to your question. Maybe it’s something where the value that’s being produced by all these images or is something that is distributed to everybody as opposed to being locked into very few silos.

TP: When I was reading your book, I guess on a personal note, I was thinking particularly things you were writing about relationships actually and how, the camera phone, the role of that place in contemporary relationships, basically and it made me think about presence quite a lot and I guess this pandemic has forced us to be present basically in that way. It isn’t ideal for a lot of people, whether it’s your relatives, your mother, or your partners and it made me think particularly about the role that the smartphone has unfortunately had to play within medical settings now, for example, hearing how people have been saying goodbye to their loved ones through that device. I just wonder how particularly Covid has changed your way of thinking really in relation to the social photo which is not a small question but if there’s any pearls of insights, I’d love to hear them.

NJ: That’s a great question. One of the dangers in writing a book about current technologies is it’s going to be out of date, just absolutely immediately, which I figured would be because more due to technological advancements than a global pandemic. However, I think the first thing that comes to mind is a point I already had made about the one of the big ways that we’re using social media differently during the pandemic – as a replacement for everyday offline experience rather than something that facilitates offline experience and so I think that is that’s a very different usage we were sort of thrown into.

For example, the tragic situations of having to say goodbye to a family member via phone. My thinking is what comes next more than it is how we’re using this stuff during a pandemic. What really excites me is how people use their phones together, while they’re traveling, so many of the things that are interesting to me just aren’t really applicable when everyone is home all the time. Though I think one thing I’ve definitely noticed is that I think people are really playing with augmented reality more right now than I had seen before. When you’re home, and you’ve already taken all the photographs, but when you add augmented reality when you can manipulate things – you could add things to the image.

You can take a million photos from your chair, right? You could take a different photo everyday from home. So I found that interesting. Certainly, I don’t know how much I’ll always tie the rise of TikTok with the pandemic, probably in my head, even though I think it probably, you know, was coming about obviously before the pandemic and I’m not sure how much it changed but certainly the domestic nature of a lot of TikToks, I think is trying to convey your personality or putting on different personalities is a big part of the content of TikTok that I hadn’t seen so much before. How much that is because your home or because you’re alone, I don’t know, I’ve been linking all these things together but it could be totally, doing that falsely, it just might have been coincidence but that personality as a medium, personality as an art is something that I’ve been seeing. That kind of answers the other question, what do you see coming up next in social media, I think that’s also a trend around personality that I think is really interesting but I don’t know if that answers your question totally.

TP: A few quick-fire questions, what’s your view on Instagram / Instagram influencers as a form of social marketing?

NJ: I’m not an expert in advertising and marketing, really anything to do with professional photography is not what I know. Certainly, I would imagine the marketers are more interested in having the everyday person take a picture of their product than they are of putting their product on a billboard anymore and getting the micro influencers or getting the everyday person to post about their product is probably central. Why would you want to pay for an expensive photographer when you get much more reach getting people to take a picture of the product on thier own. The professional photographer, what can they do, they can create a really interesting and compelling photograph but what really compels buyers is probably that their friend took a picture of it, just that a can of soda is in my friends hand is probably going to make me want to get that soda more than the best billboard campaign. So again, I’m speaking completely outside of my expertise, so maybe somebody in marketing or sales could totally tell me I’m wrong there. That’s just my assumption.

TP: In terms of social media and social photography, do you not think that it has advanced in the area of tourism and that it has actually played a big part in tourism because people always have their mobile phones so it’s helped economically?

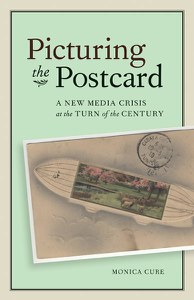

NJ: I love reading tourism studies, books on tourism. There was a really great book that

came out last year by Monica Cure called Picturing the Postcard and it’s a history of the postcard and it’s told through the lens of a media crisis. Postcards have always been looked down upon and in tourism studies there’s always talk about travel versus tourism. Travel is when you really go to a place and you experience the real culture and tourism is just for when you want to go see the the main attractions; the Eiffel Tower and Big Ben and of course that distinction is completely class based. It’s basically wealthy people do one and poor people to the other and it’s a distinction I think is very problematic and so the the postcard and the selfie get have been talked about very similarly throughout history. In that, ‘oh, look at these people, they’re just here to take a selfie’. You know, they traveled to this place, they went to the greatest view, got the selfie, got out, they were probably on their phone the whole time, they didn’t actually experience it. So I love the conversations around, travel, and image taking and there’s some sections in the book about how taking pictures makes you feel like you spent your time wisely traveling to a place and or even sometimes today that you take so many pictures, that you may choose not to take photos on this vacation. I think those things are really, really interesting but I definitely caution against the idea that taking pictures inherently removes you from your vacation or takes you out of the moment but it kind of depends on how you do it. I think you can take pictures. You can let the camera get away, get in front of your vacation, or get in the way of your vacation big time. That can happen and I definitely see that a lot. That definitely does happen a lot but I think that’s a really, really good topic and if you’re interested in that the book Picturing the Postcard is one I’d really recommend.

TP: What do you think the responsibilities social media companies have towards the mental health of thier users, things like facial dysmorphia now is on the rise because of augmentations with filters and things like that and just the mental health implications?

NJ: That’s a great question. I remember five or ten years ago it was very difficult to get people to even think about this stuff or talk about this stuff and now I think it’s really part of everyday conversation which is really good that this is even being brought up and being brought up routinely. I think it’s forced the companies to respond and to think about these sorts of things, so for instance, like dysmorphia and the filters. I think filters are really fun and exciting when they allow you to play, when they allow you to express yourself in different ways, but then when those filters instead push people towards conventional or normalise standards of beauty, of facial shape, of skin lightening all these various things…. This gets back to the metrics – that people like people will use filters that make them seem skinnier or make thier eyes bigger. Things that convey youthfulness, and whiteness and all these vary, normalised ethnocentric versions of beauty or standardness acceptableness. All these various things are very popular and but at the same time make people feel really bad, right? They make people feel bad when you are constantly confronted with having to alter the way you look in order to fit a kind of standard. It’s also difficult around older people in general taking selfies and using camera based apps because culture has told them that their face isn’t photogenic, which is terrible. I think that is it’s a difficult thing to ask tech companies to solve, obviously, these things go well beyond just technology, social media and cameras, but at the same time it should be very easy to ask technology companies not to exacerbate these problems and to be aware of them and do you want to penalise users when you know that your filters are pushing people towards normalisation rather than through like expression….? Then, I think that’s something that should be regulated absolutely.

TP: Post pandemic – do you think we’re going to see a retreat almost as a detox from some of these social media outlets?

NJ: I have a hard time answering that outside of my own opinion. Personally, I cannot wait to spend way less time on Zoom and way more time going to shows but in general, it’s obviously changed the way that workplaces are thinking about how thier offices look and operate. Here in the United States, in the big cities offices are very expensive and then people would much rather be dispersed and save some money. Workplaces are going to be organised differently, schools are going to be organised differently. Some of this stuff is going to linger and it’ll be interesting to see what does and what doesn’t. But as far as I think, people are will be very ready to not use social media as a replacement for in person experience. I know there’s some people that think that once we get a taste of all this stuff, that will probably never want to leave our house again. I run a conference called, Theorising the Web and we usually pack rooms full of people. When am I going to be able to do that again? Will I even be able to do that next year? What’s the appetite for people to go and get really crowded into a conference room, into a club, into a pub. That’s a really good question. I don’t have a great answer for that, it’s going to be really interesting and we’re all going to probably navigate that differently.

TP: I’m just wondering if Susan Sontag were alive today would you consider her a disconnectionist? How do you think she would be talking about social media? Would she take the same view as Sherry Turkle perhaps?

NJ: That’s a great question. Certainly one I would only be guessing at, I’ve thought about that before, if social media was around what her sort of usage of it might be. I mean, just in her own time she engaged in current events very little. She engaged in part of the television formats that were emerging in her lifetime, very little. She wasn’t a big fan of what was happening today. It just wasn’t what she was into. She liked writing books and reading, she like reading and writing. So if I had to guess, I think Susan Sontag would never use social media but not be completely against it. I think that’s where she would land. I think she would be pretty uninterested in the whole endeavour, though.

TP: What’s the first social media app that you go to every day and why?

NJ: It’s usually Snapchat, that’s where my family is at and so I haven’t gone to see my family a whole lot in the last year. I don’t want to look at social media, really at all, my habit usually is wake up and I like to read. If I look at Twitter first thing in the morning, I feel like my brain is broken, I’m not going to get anything interesting done that day, I’m just gonna start looking at news and I’ll open up a bunch of tabs of a bunch of people typing out their opinions.

TP: Nathan, that’s a really optimistic finish!

NJ: Thank you for having me and for reading the book and also wonderful conversation.

*This is an edited version of an ‘in conversation’ between Nathan Jurgenson and BA Photography and MA Photography at Falmouth University (2021)

Follow tracey paddison on Instagram

Routledge Award Winner: Winter 2022