Struck By Light at Valid World Hall (2021)

What is a 21st Century photograph? what does a 21st century photograph look like?

By Megan Ringrose (19th July 2021)

By Megan Ringrose (19th July 2021)

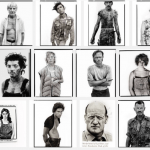

Ellen Carey, U.S based experimental artist posed this question to women photographers worldwide, in an open call hosted by Hundred Heroines in 2020. ‘Light’s immateriality challenges its makers today, analogue versus digital, doubles our challenges. It is here, in the early stages of modern and contemporary art with its roots in photography, that our work has context.’ this exhibition symbolises strength and resilience, a 21st century version of The Linked Ring.

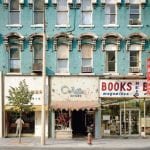

Valid Word Hall, Barcelona, Spain: 21st – 31st July 2021

Participating Artists:

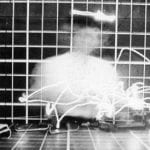

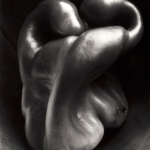

Ellen Carey:

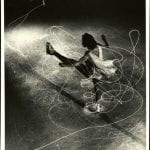

Ellen Carey is an educator, independent scholar, guest curator, photographer and lens-based artist, whose unique experimental work spans several decades. Photography Degree Zero names her large format Polaroid 20 X 24 lens-based art, which she began using in 1983 under the Polaroid Artist Support Program. Struck by Light (1992-2018) finds her parallel practice in the darkroom with the camera-less photogram, a process from the dawn of the medium, discovered in the 19th century by William Henry Fox Talbot, both photogram and the phrase drawing with light continue today. Her experimental investigations into abstraction and minimalism, partnered with her innovative concepts and iconoclastic art making, often use bold colours to create new forms. Colour and light are the link between her two practices; light, photography’s indexical, is used a lot or a little or none at all; its absence or zero.

Jessy Boon Cowler:

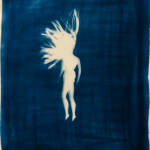

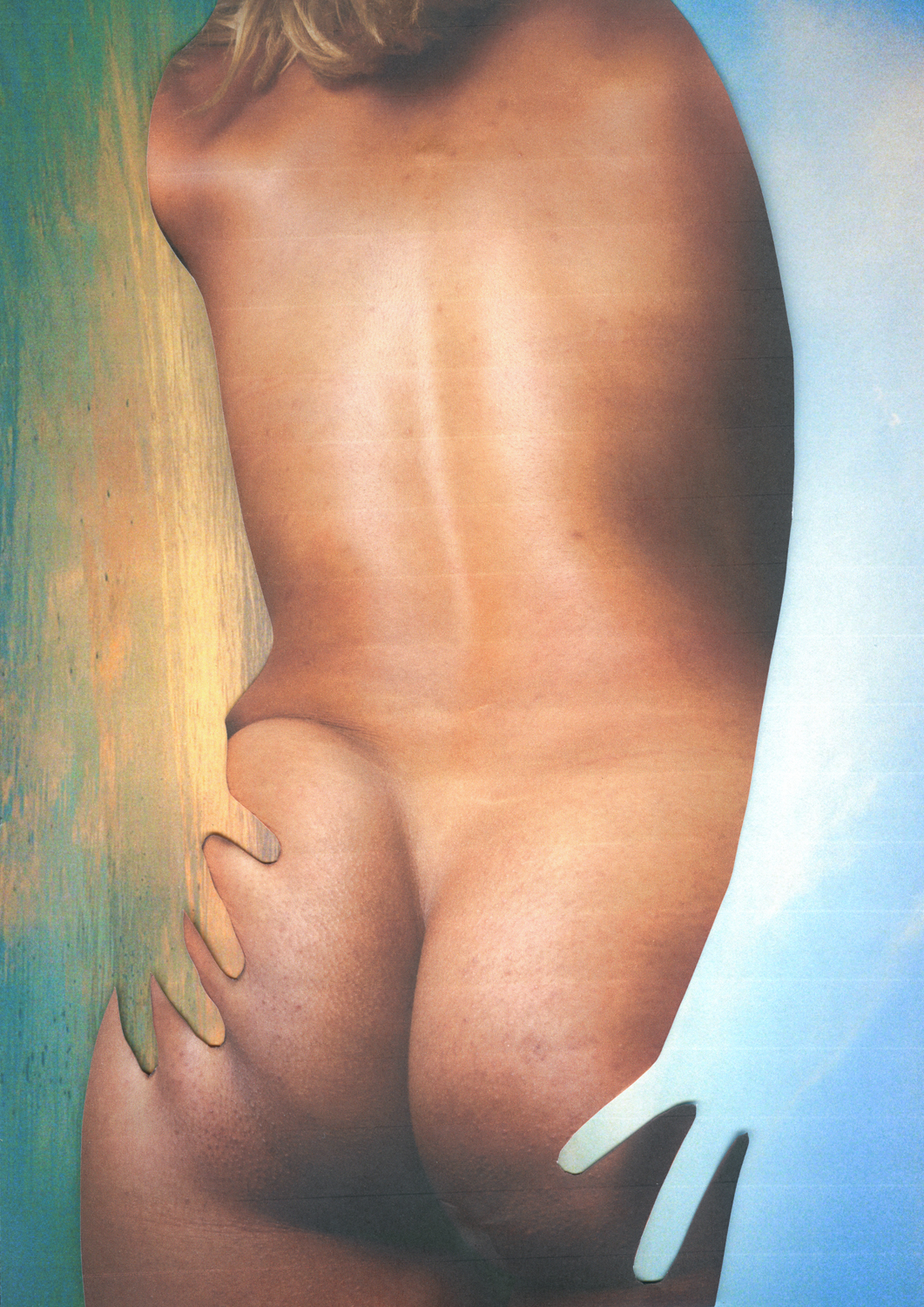

Jessy Boon Cowler lives and works in South London, United Kingdom. She is interested in the relationship between the physical versus the intellectual, specifically the common exclusion of one from the other within British culture, which leads to frustration and a need to escape. The desire those of us from cold countries hold for the South, the fantasy of an island retreat; the exoticisation of a foreign land where we can let go of our inhibitions, the shame felt due to an inherited history of colonisation.

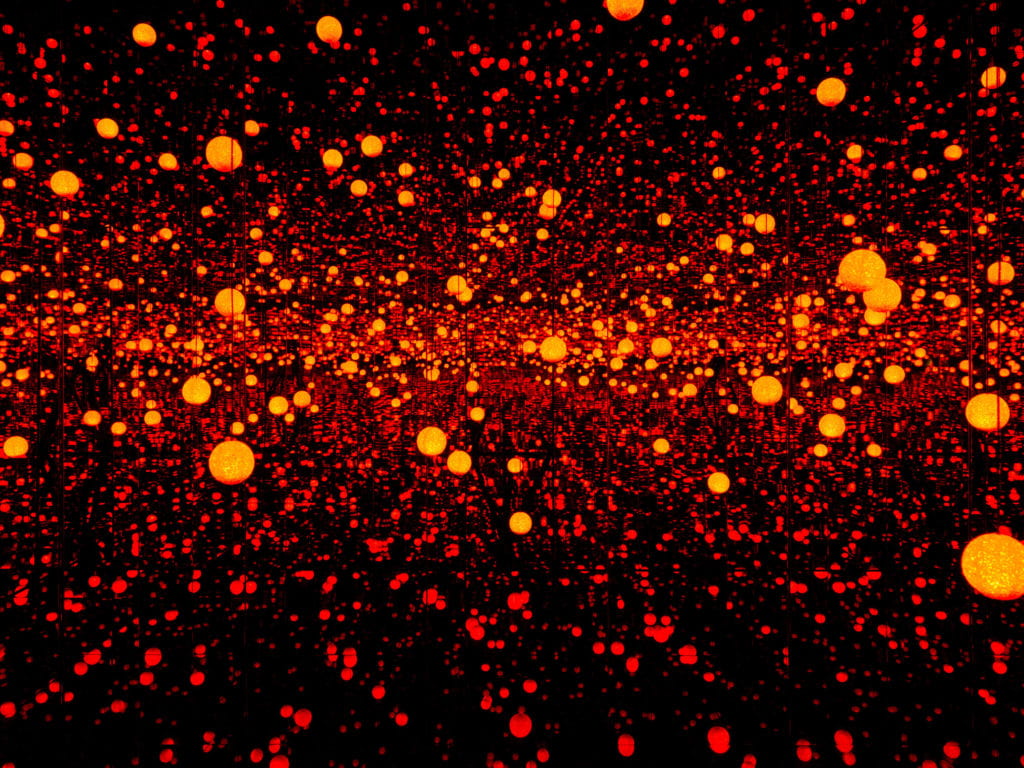

Nettie Edwards:

Nettie Edwards lives and works in Gloucestershire, United Kingdom. Edwards is fascinated by humanity’s biological, philosophical, and spiritual relationship with light and colour, particularly, as her family genealogist and photo archivist: in the role played by light as an agent of memory. Her work is practice led, experimental and site specific, fuelled by her insatiable curiosity. Wide-ranging themes emerge from immersion in residency locations; long-term historical research projects and working with photographic archives.

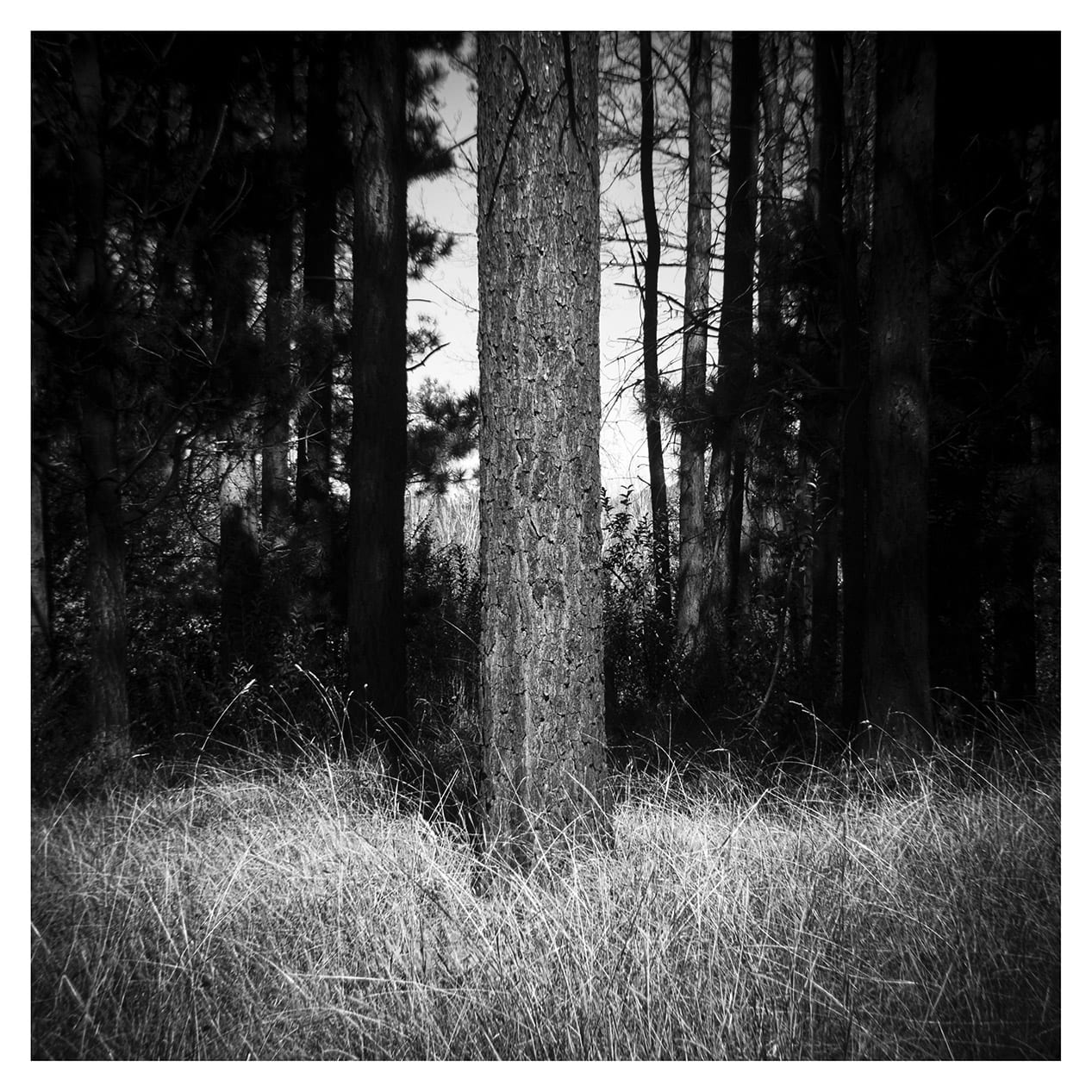

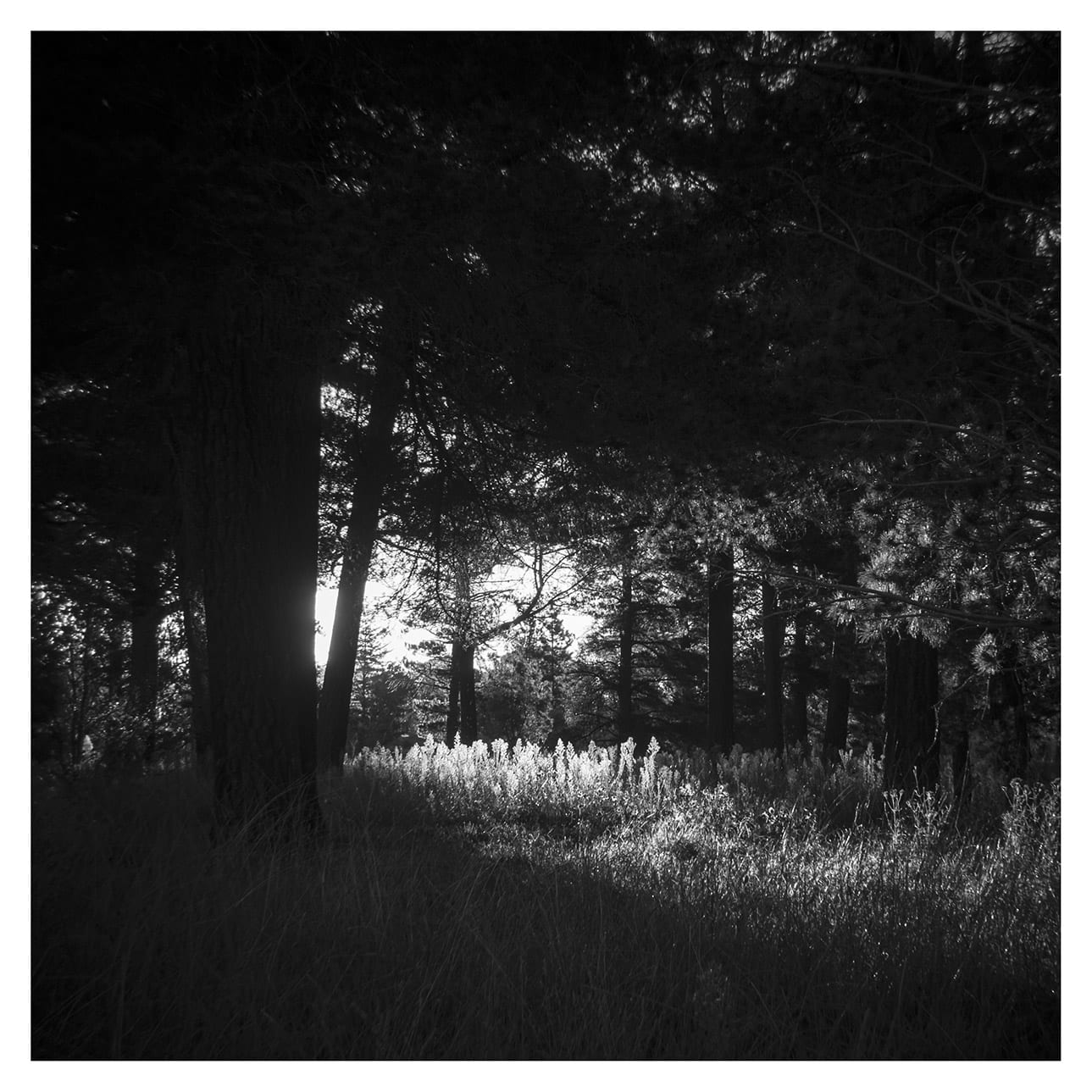

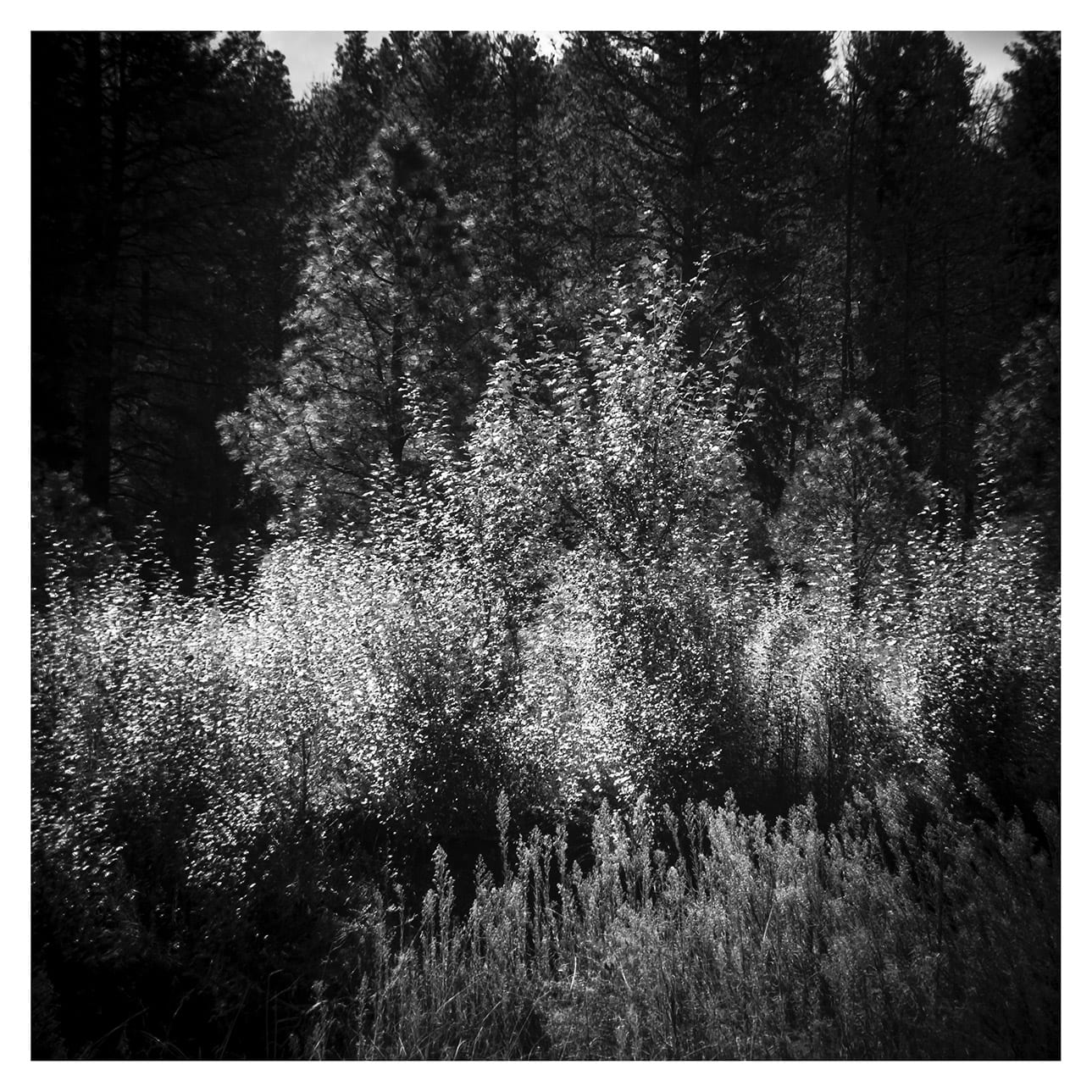

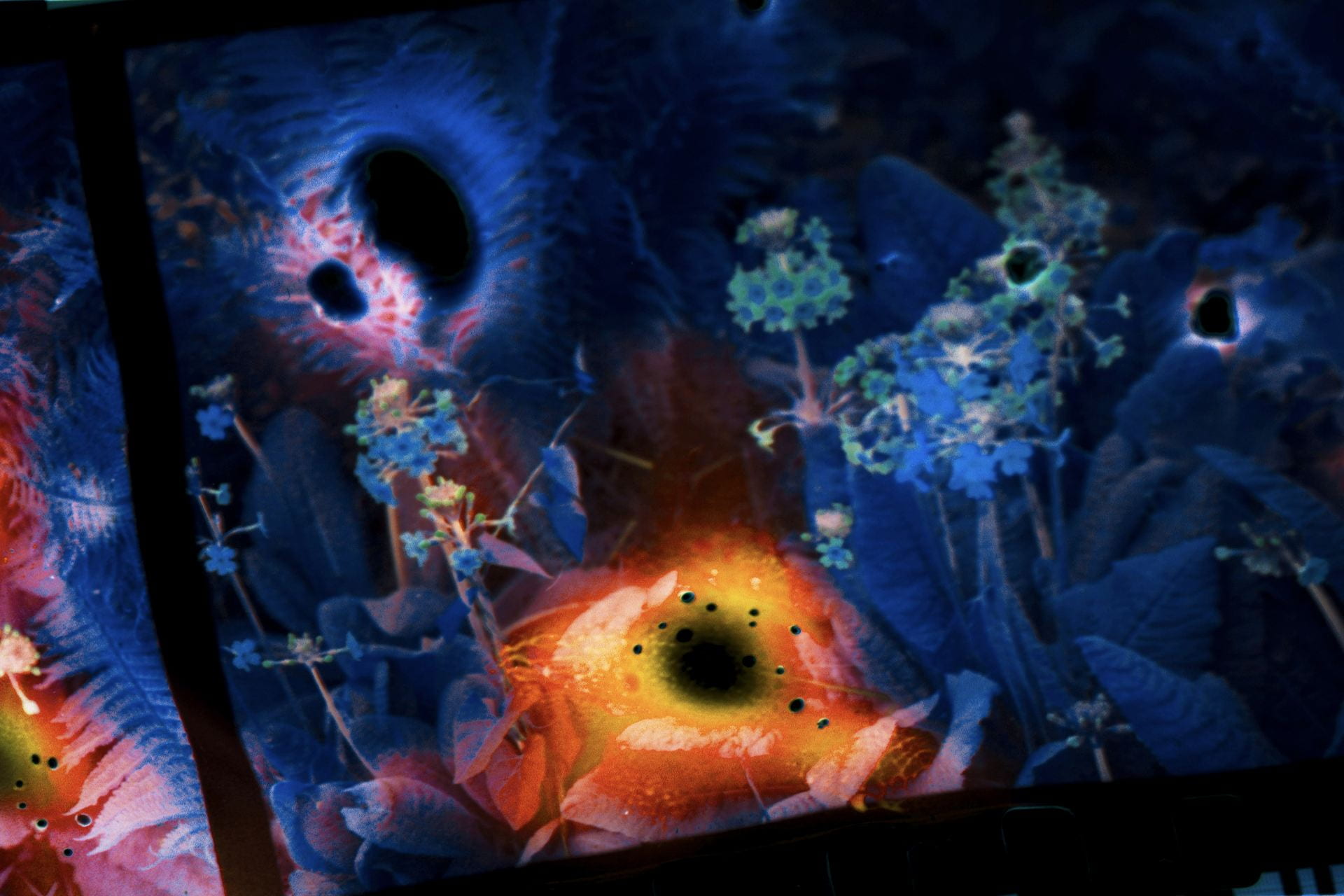

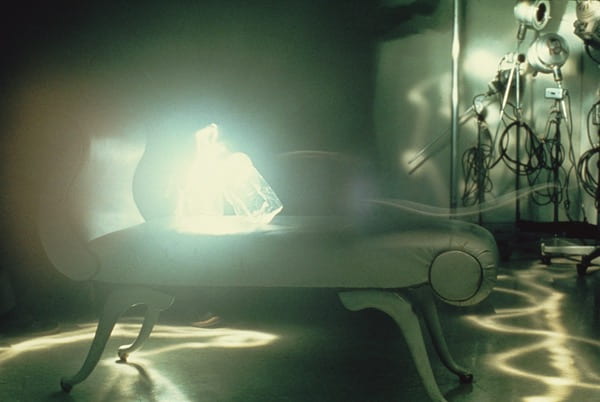

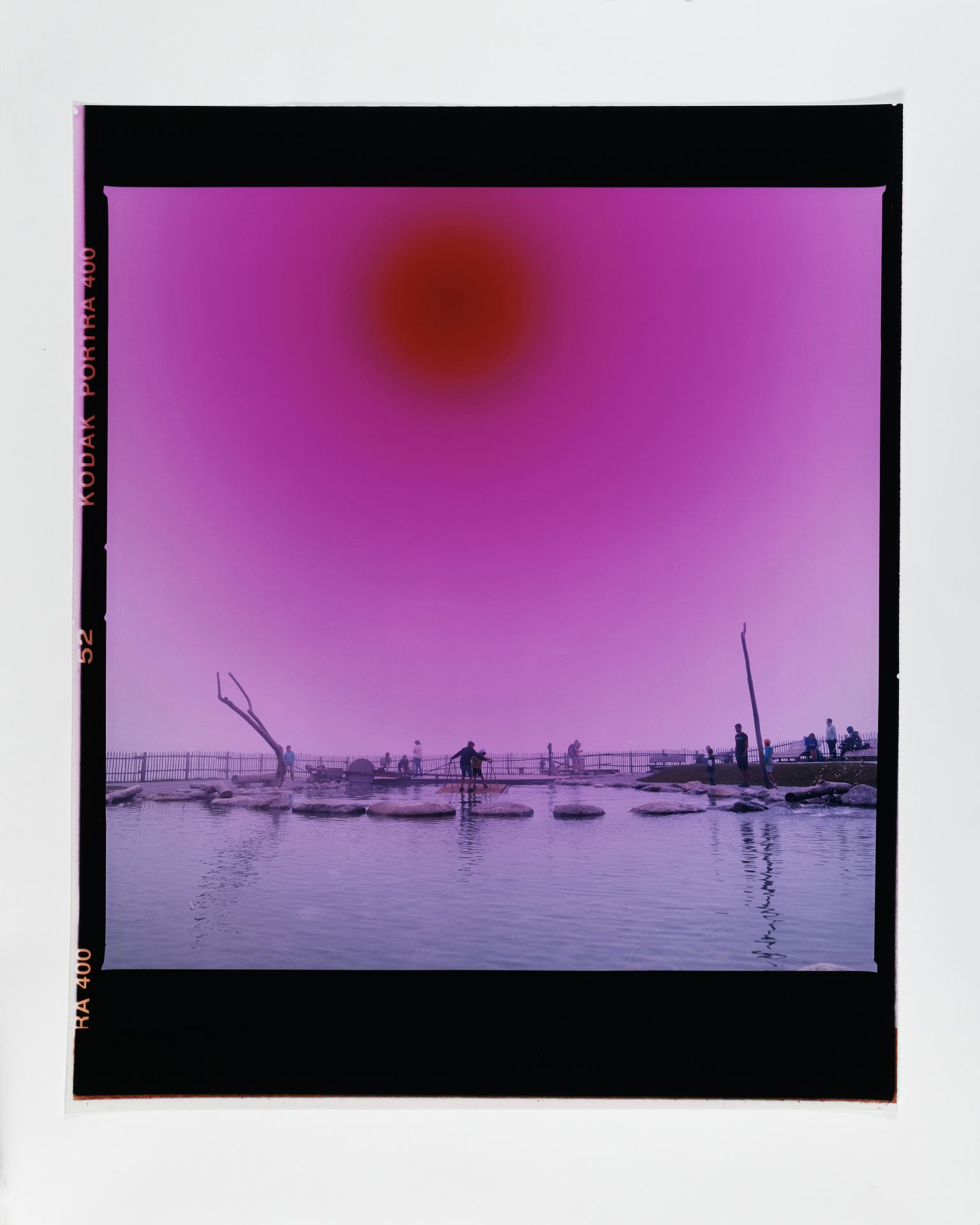

Cristina Fontsare:

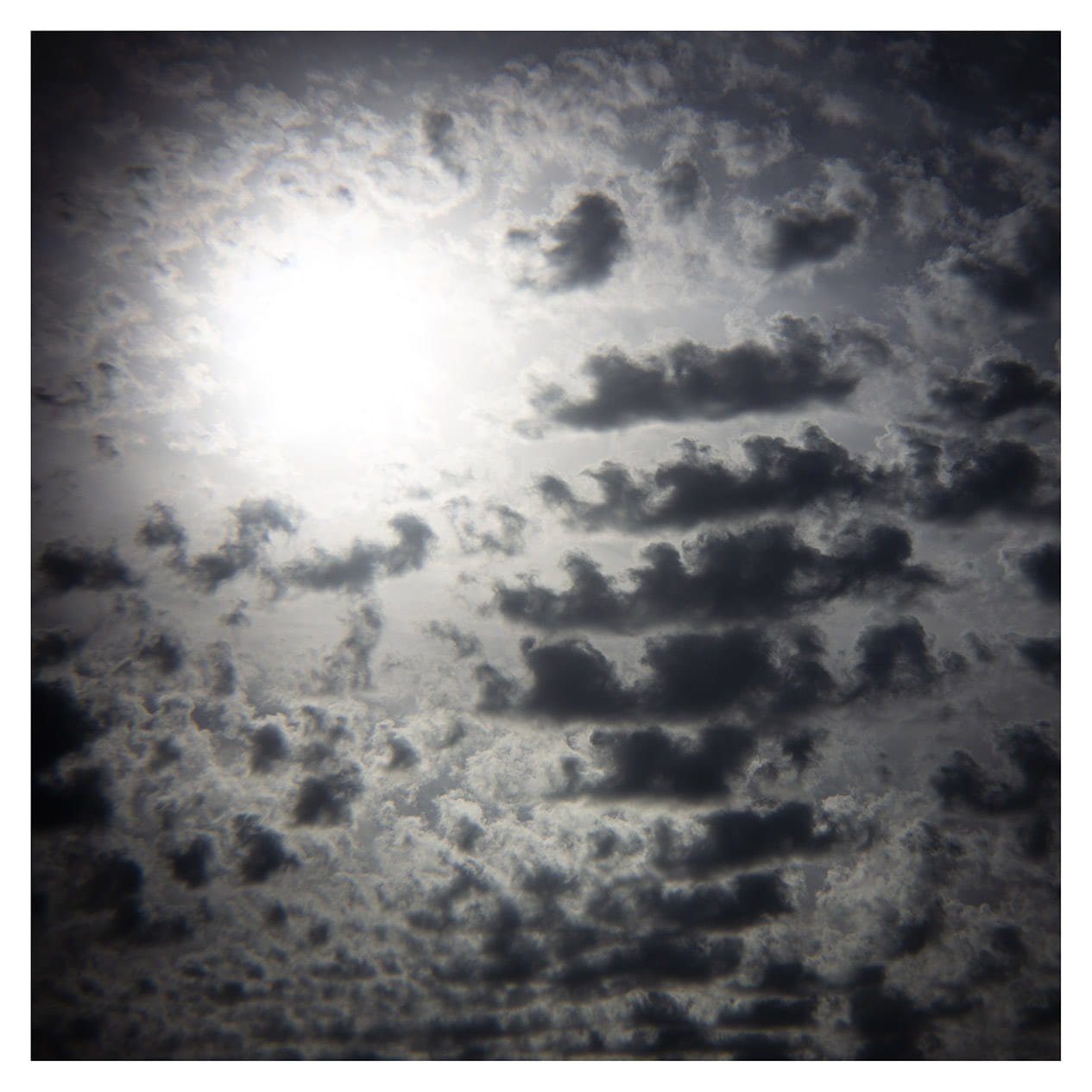

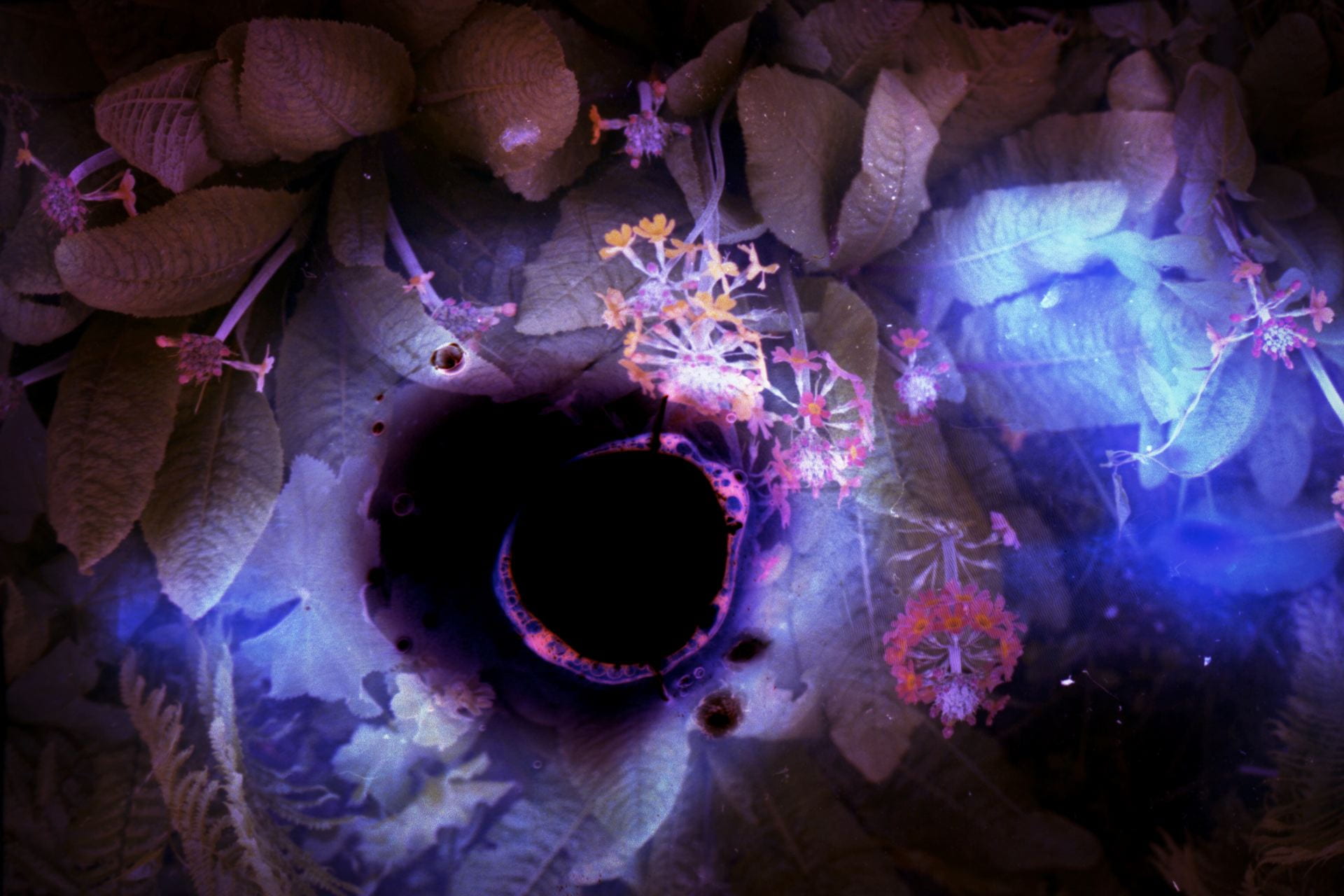

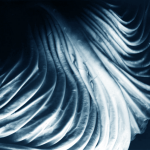

Cristina Fontsare is based in Catalonia, Spain. Her practice employs Polaroid film shot on location and post-production manipulation. The project, Journey to the Centre of the Earth started on a family trip around caves and ancient forest in the Basque Country in the north of Spain. This inspired an imaginary journey in the search for MARI, the main deity of Basque mythology. She is the manifestation of the divinized forces of nature. Queen of the three kingdoms, Mineral, Vegetable and Animal and the four elements: Earth, Air, Water and Fire.

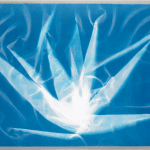

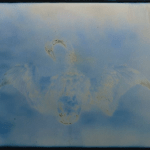

Liz Harrington:

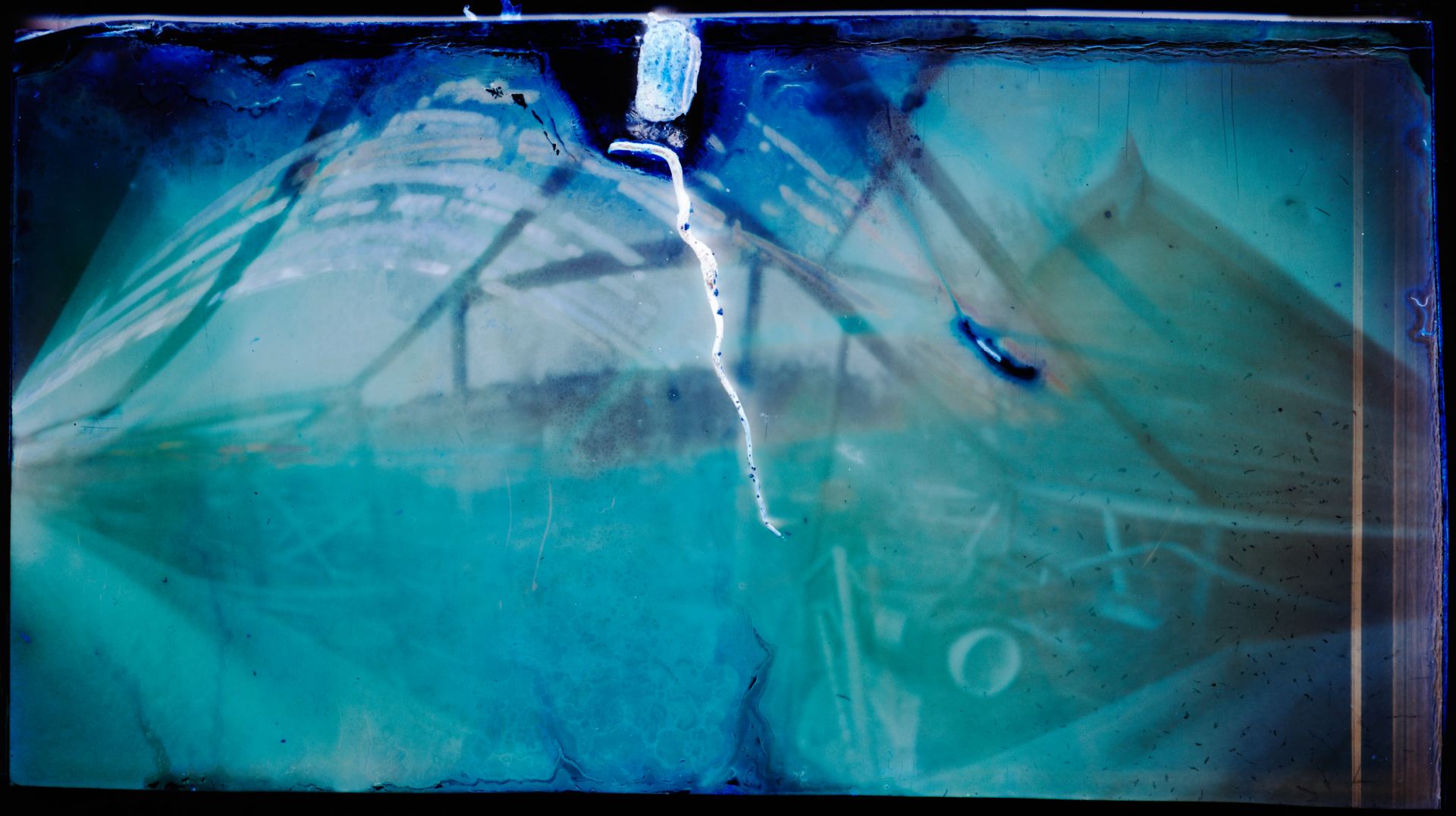

Liz Harrington is based in Hertfordshire, United Kingdom, she is photographic artist specialising in analogue photography, alternative processes and camera-less techniques. Her work explores the theme of transience – the changing nature and fragility of environments, and traces of the past. The work is experimental and archival in nature, often finding beauty in the unseen or overlooked. The exhibited works consist of a series of camera-less cyanotype images made by physically immersing the light sensitive photographic paper in the sea during periods of low and high tide. The images capture fleeting traces of the waves and wind – and of the past – at the shoreline.

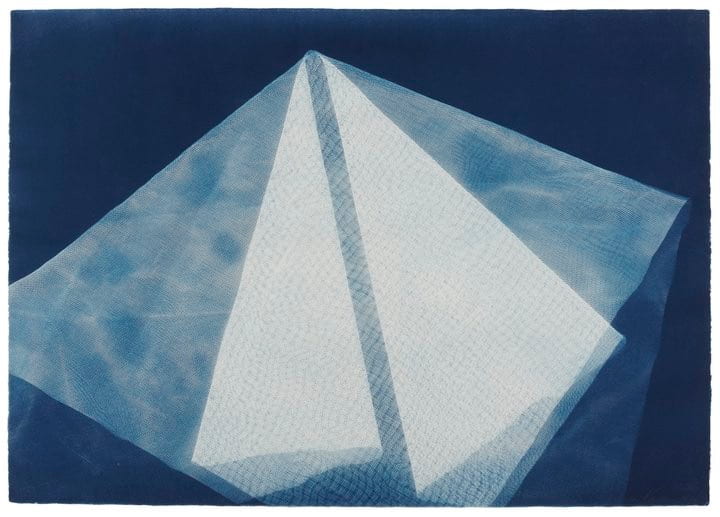

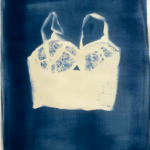

Poppy Lekner:

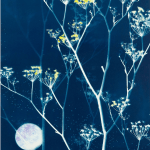

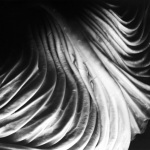

Poppy Lekner is based in New Zealand, her work is sometimes purposefully biographical and sometimes simply the results of play generated from a desire to explore an object with light, or explore the light itself. Cameraless photography and experimental photography provide a space to play that is neither purely photographic nor painting but somewhere in between. There is a directness of contact with the object and the photosensitive medium/surface that has kept her fascinated with this mode of working.

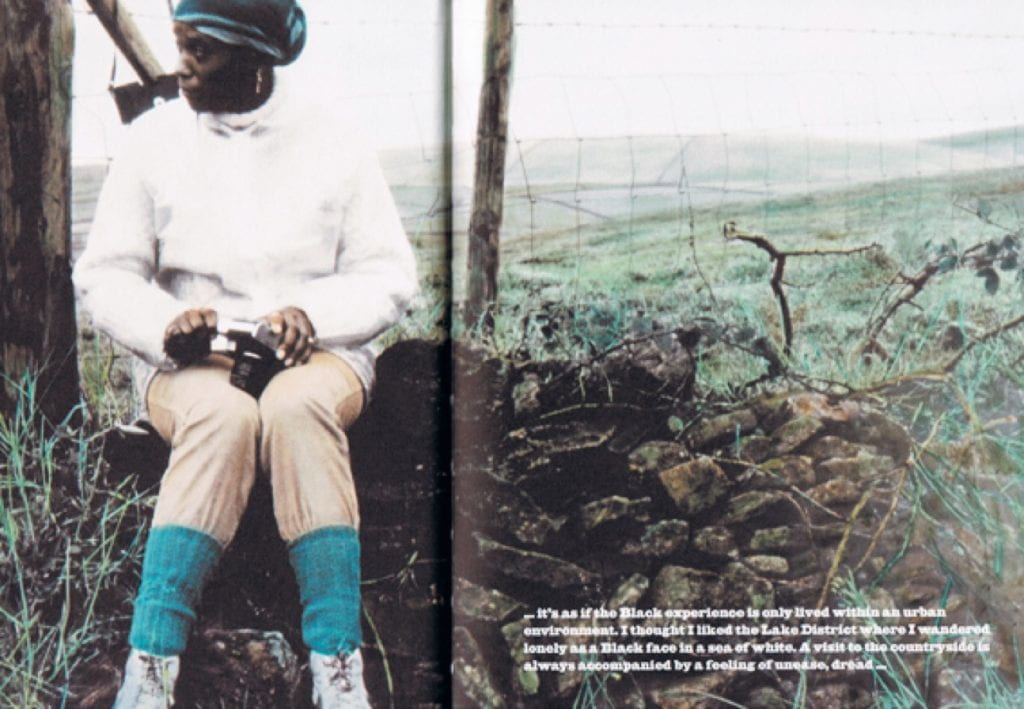

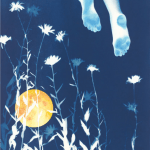

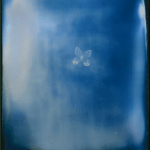

Ky Lewis:

Ky Lewis is based in London, United Kingdom, her approach to working experimentally is based in the slow lane, she works in a variety of ways using both camera-less and pinhole traditional and alternative processes. Lewis prefers a more serendipitous workflow, allowing accidents to steer work into new directions. The work in the exhibition is part of Lewis’s Solargraphic works which were set up to determine via the process of a double durational study of what influence the environmental conditions would have on the contents. Seeds were planted inside the pinhole cameras with 10ml of water. The cameras contained silver gelatine paper. The photo paper would record the passage of the sun and during the sixty day period the seeds would grow, toward the light.

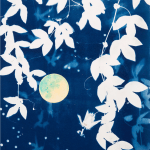

Anna Luk:

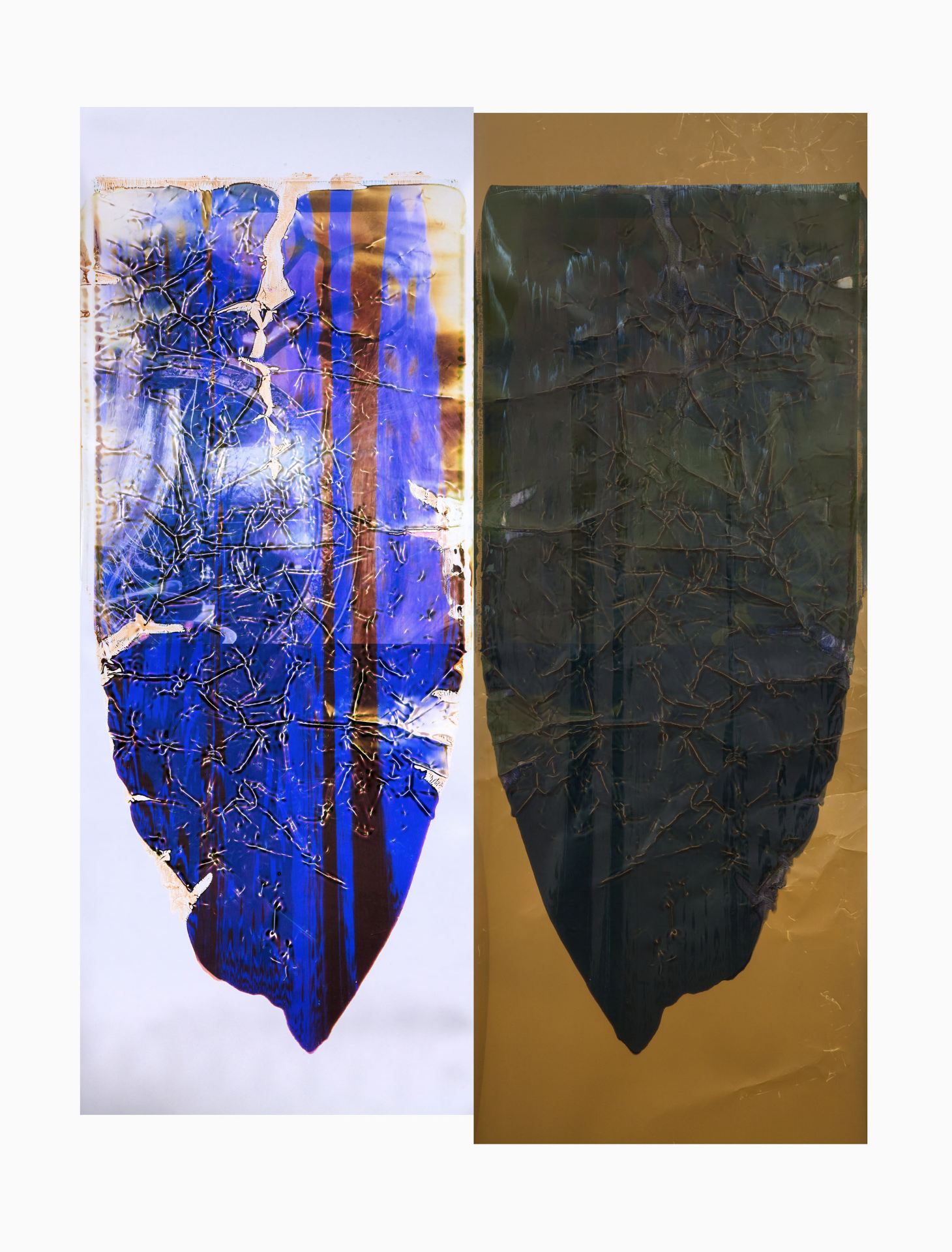

Anna Luk lives and works in London and Kent, United Kingdom. Luk’s practice explores the ontology of photography by pursuing qualities typically tethered to painting and sculpture. She works with the materiality and the ability of the medium to not only depict an external subject but also record the physical actions exerted on it.

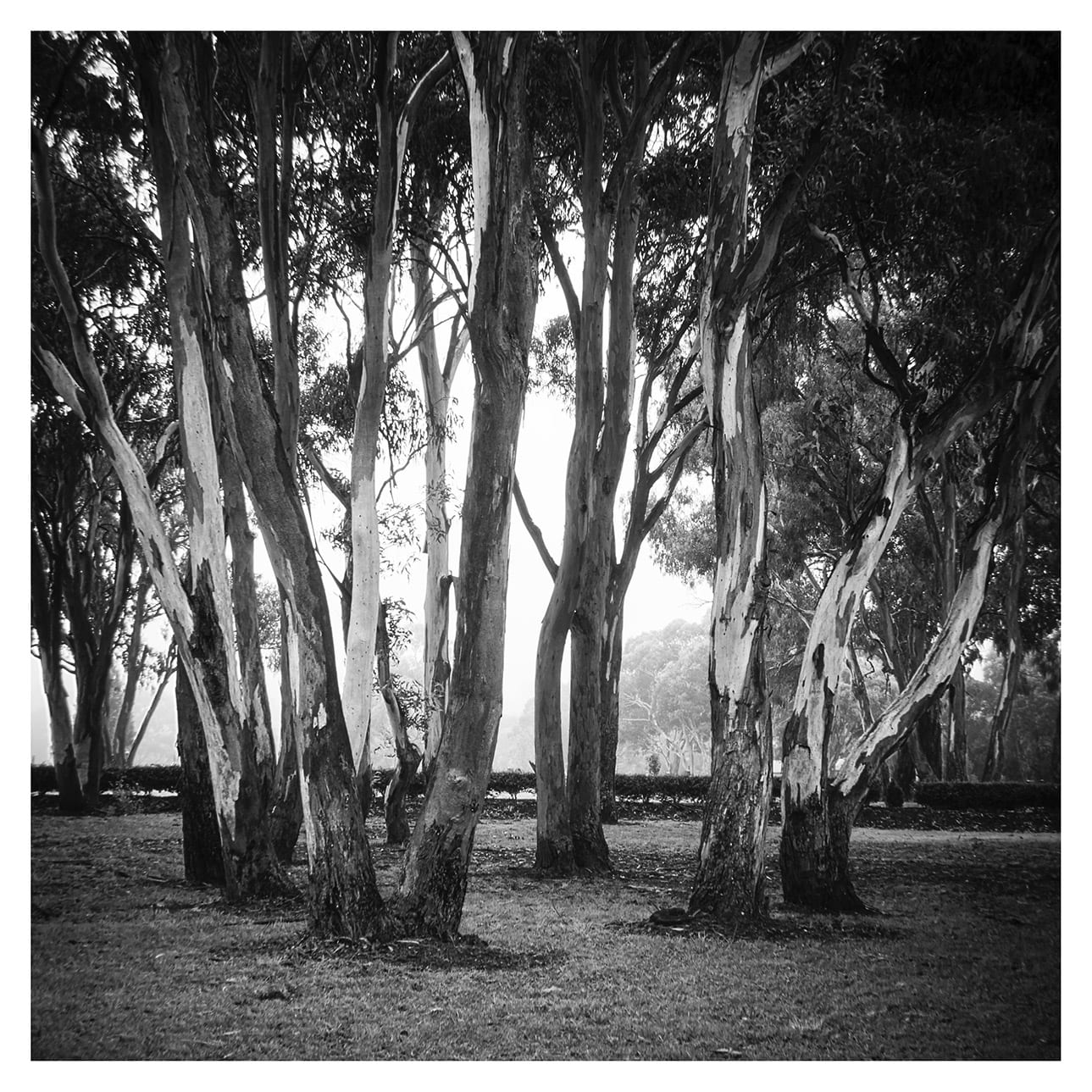

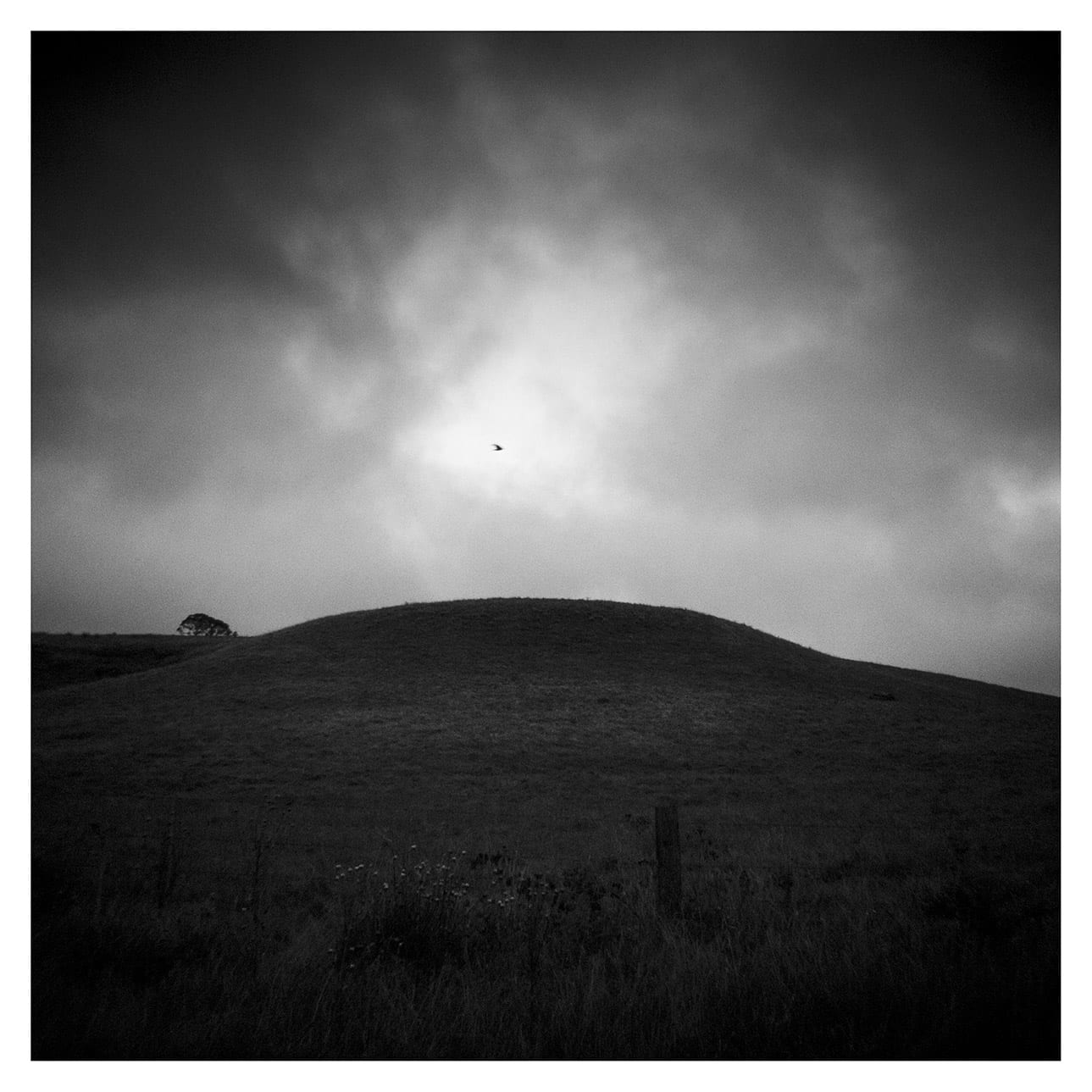

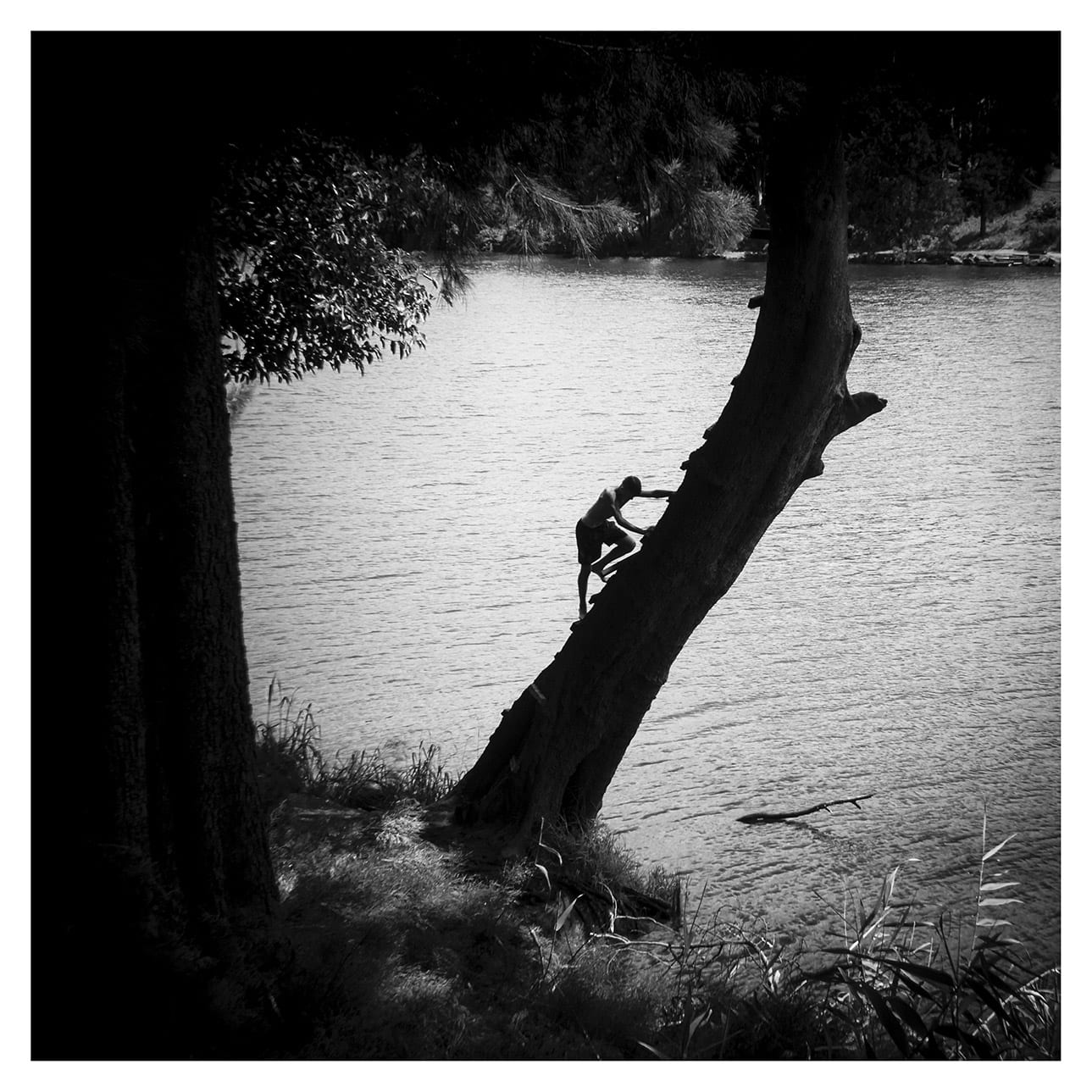

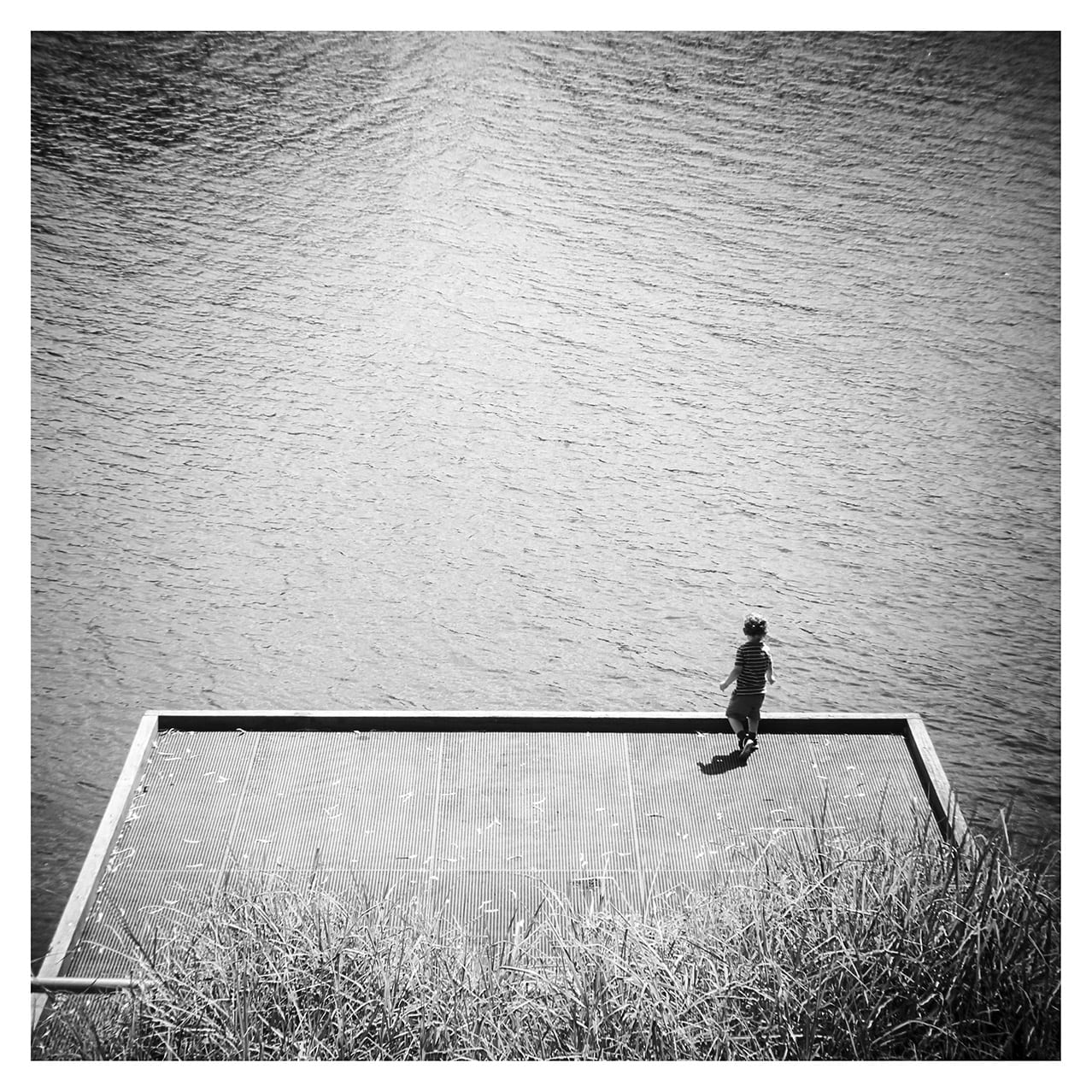

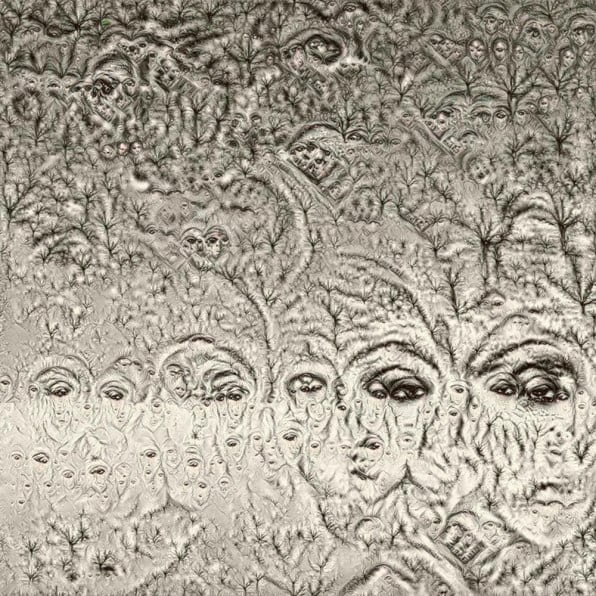

Sonia Mangiapane:

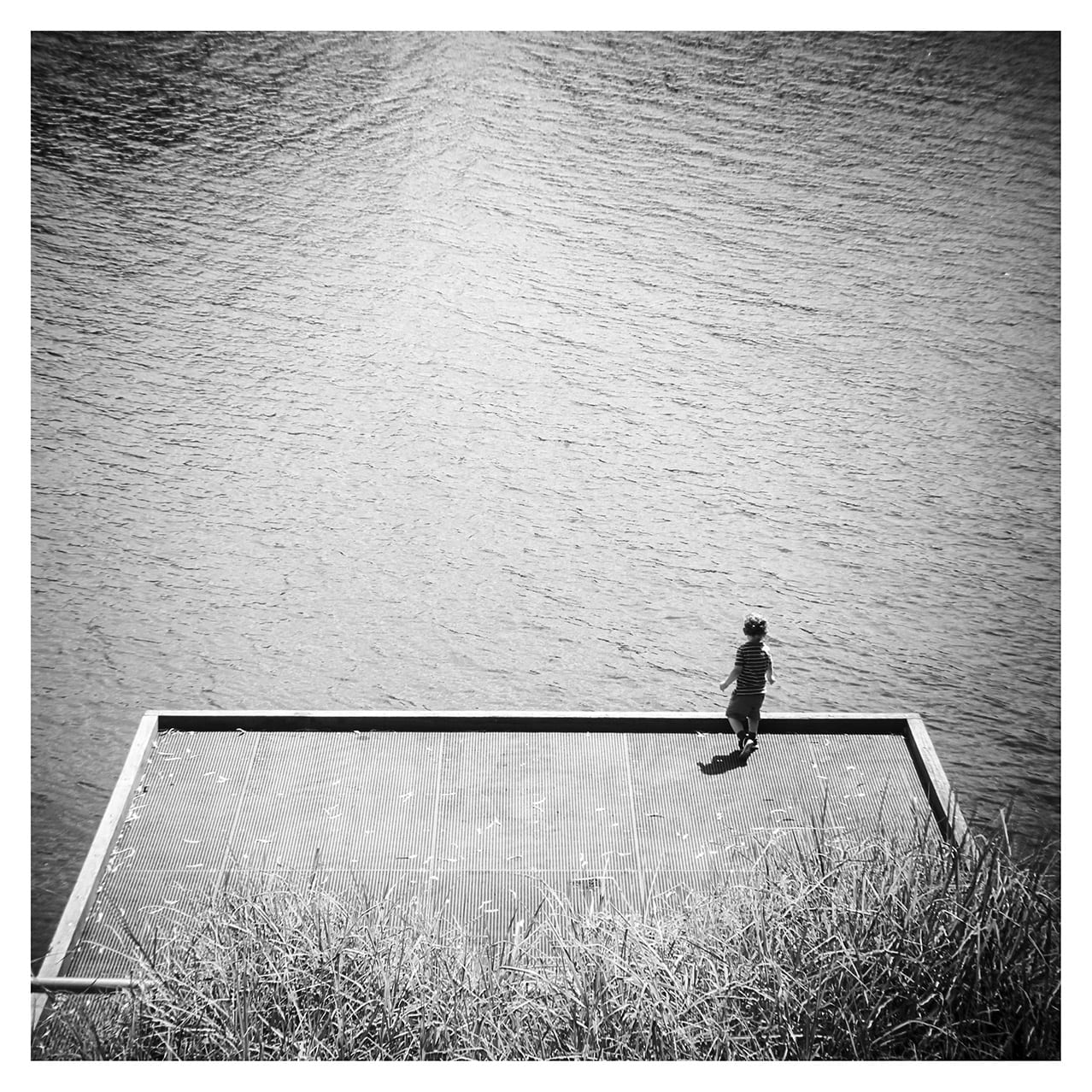

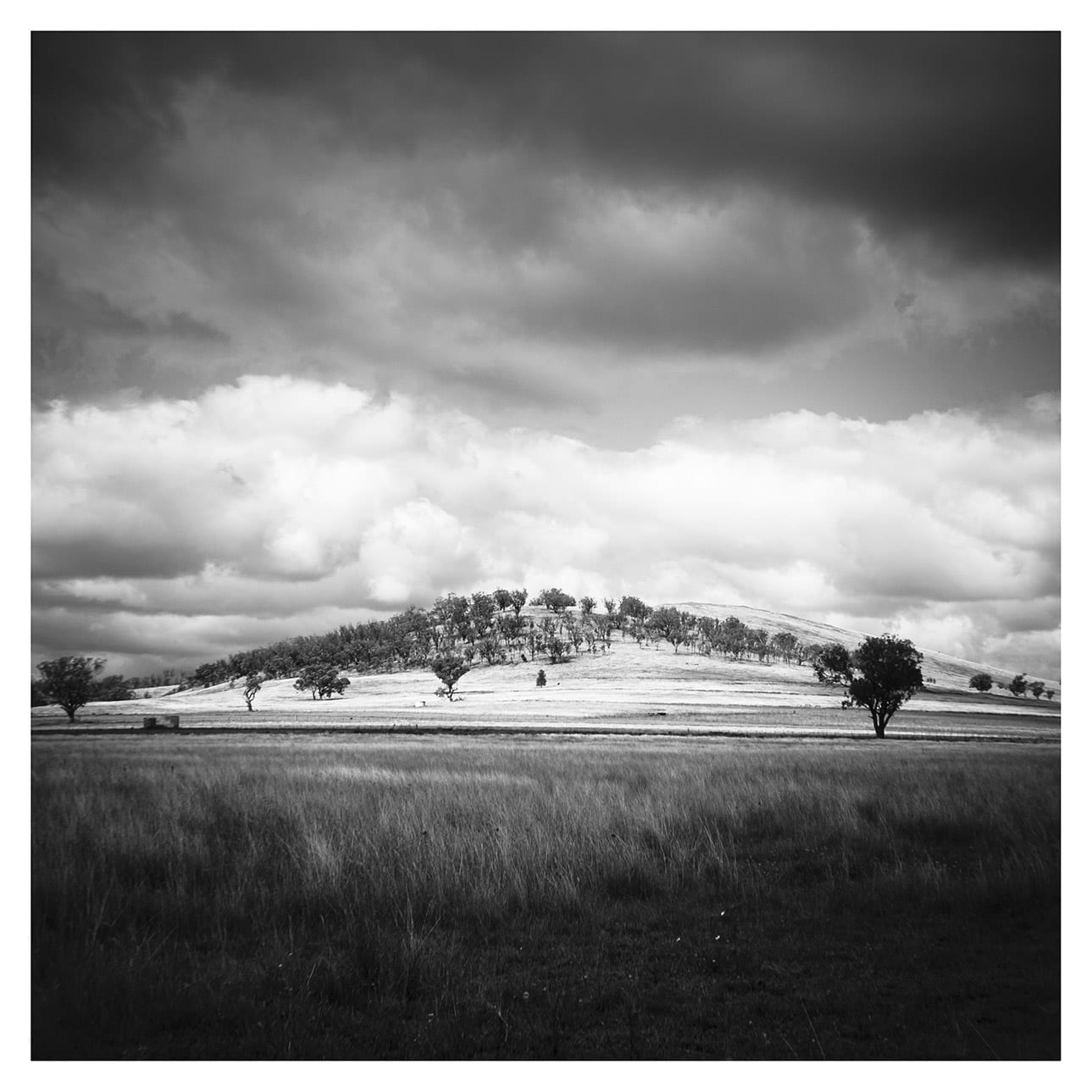

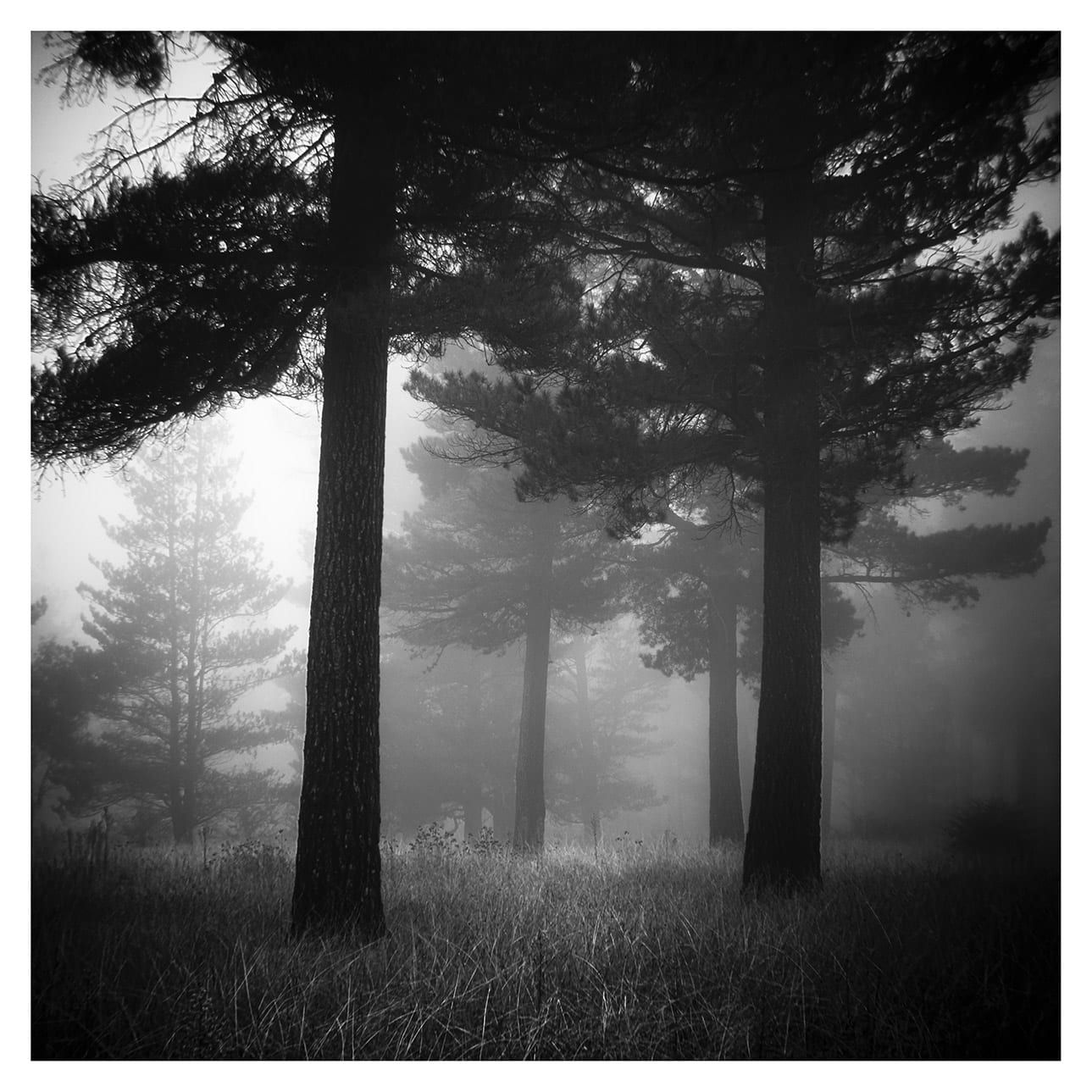

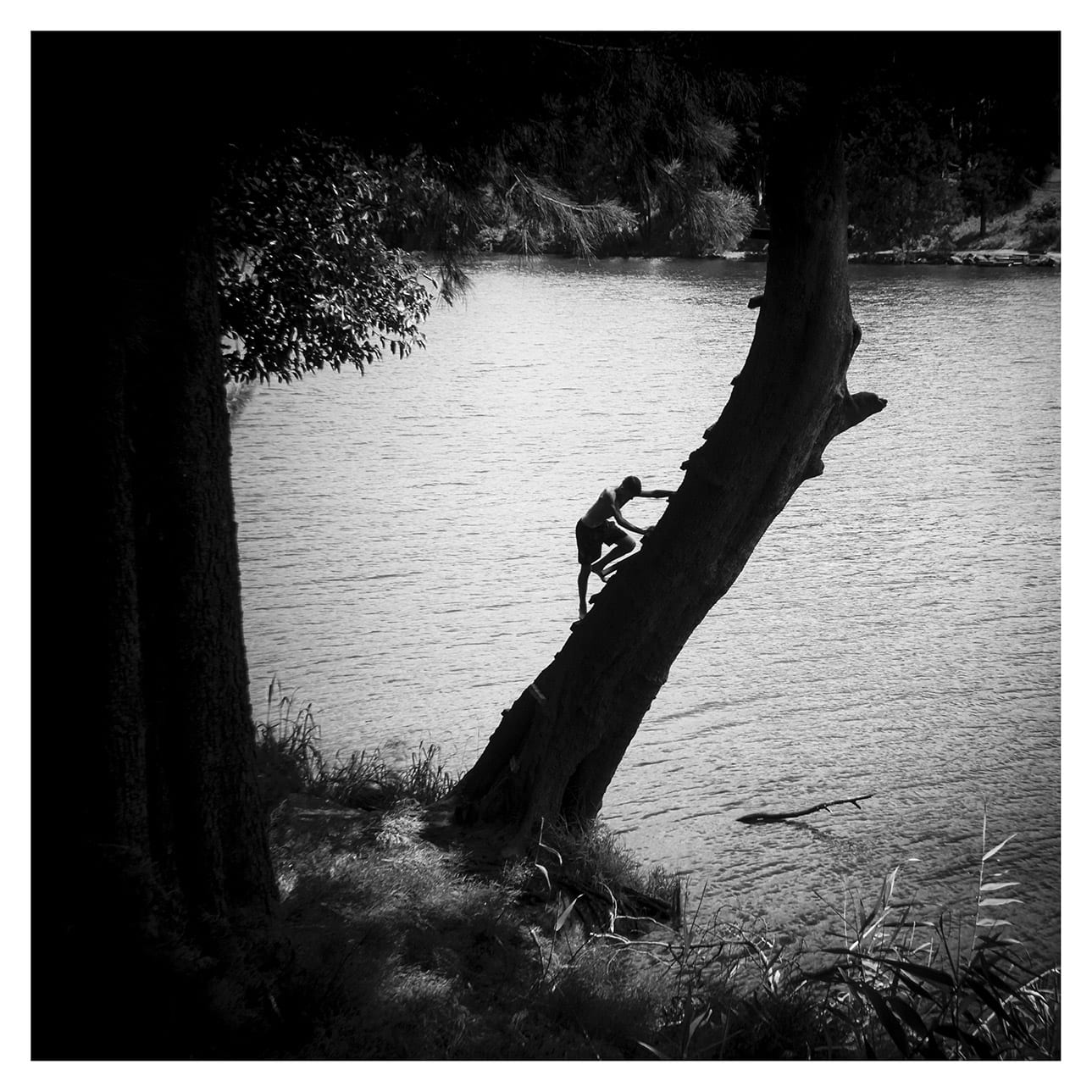

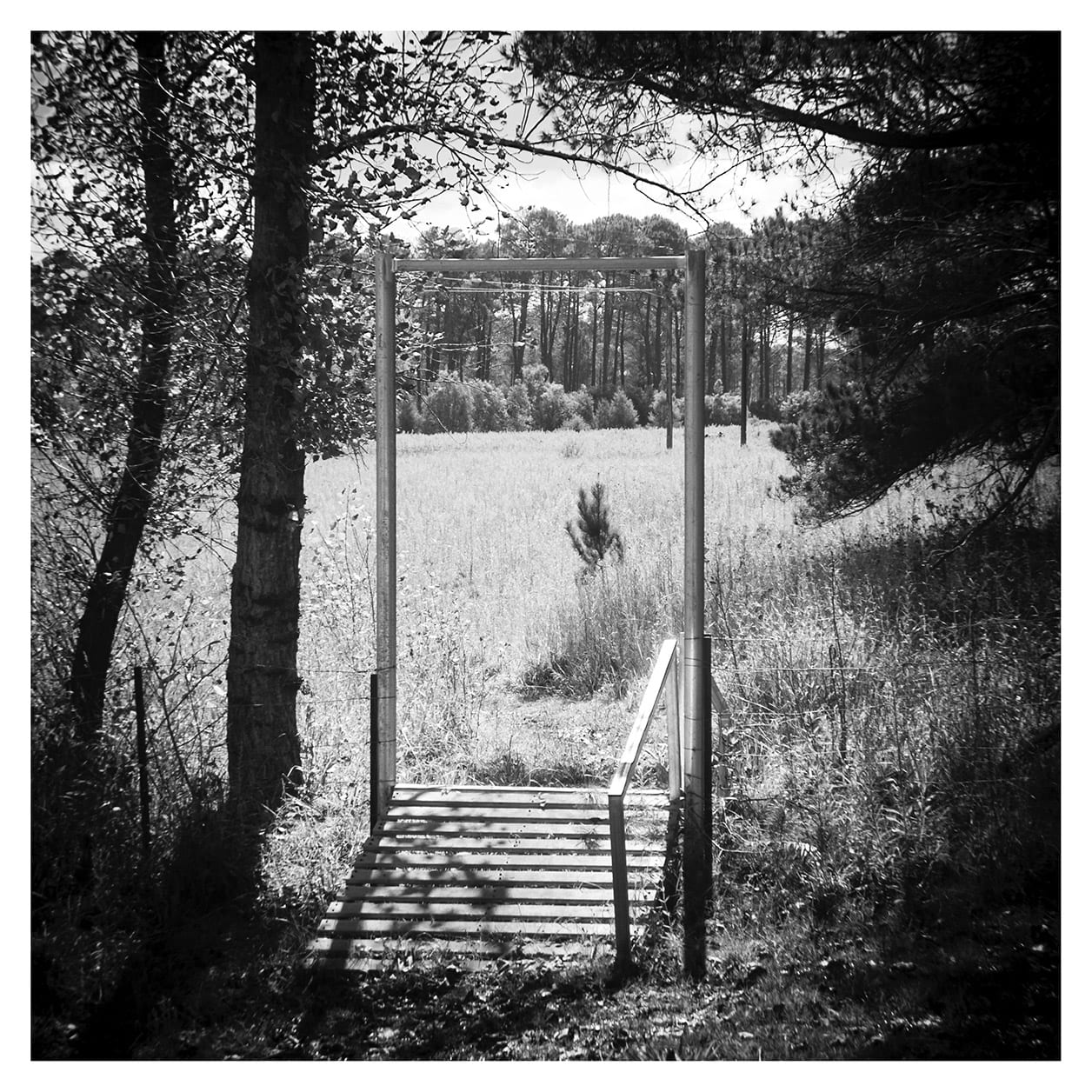

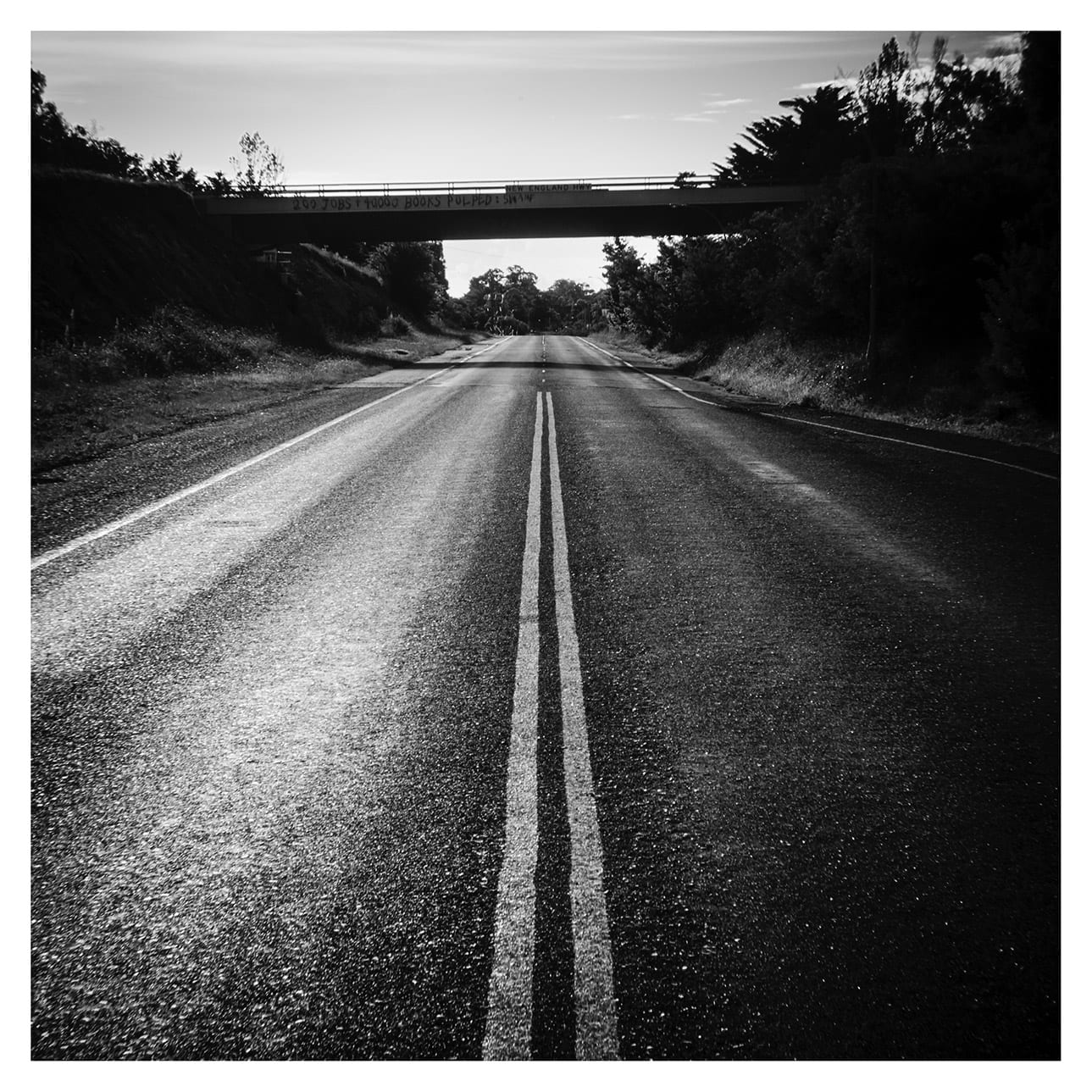

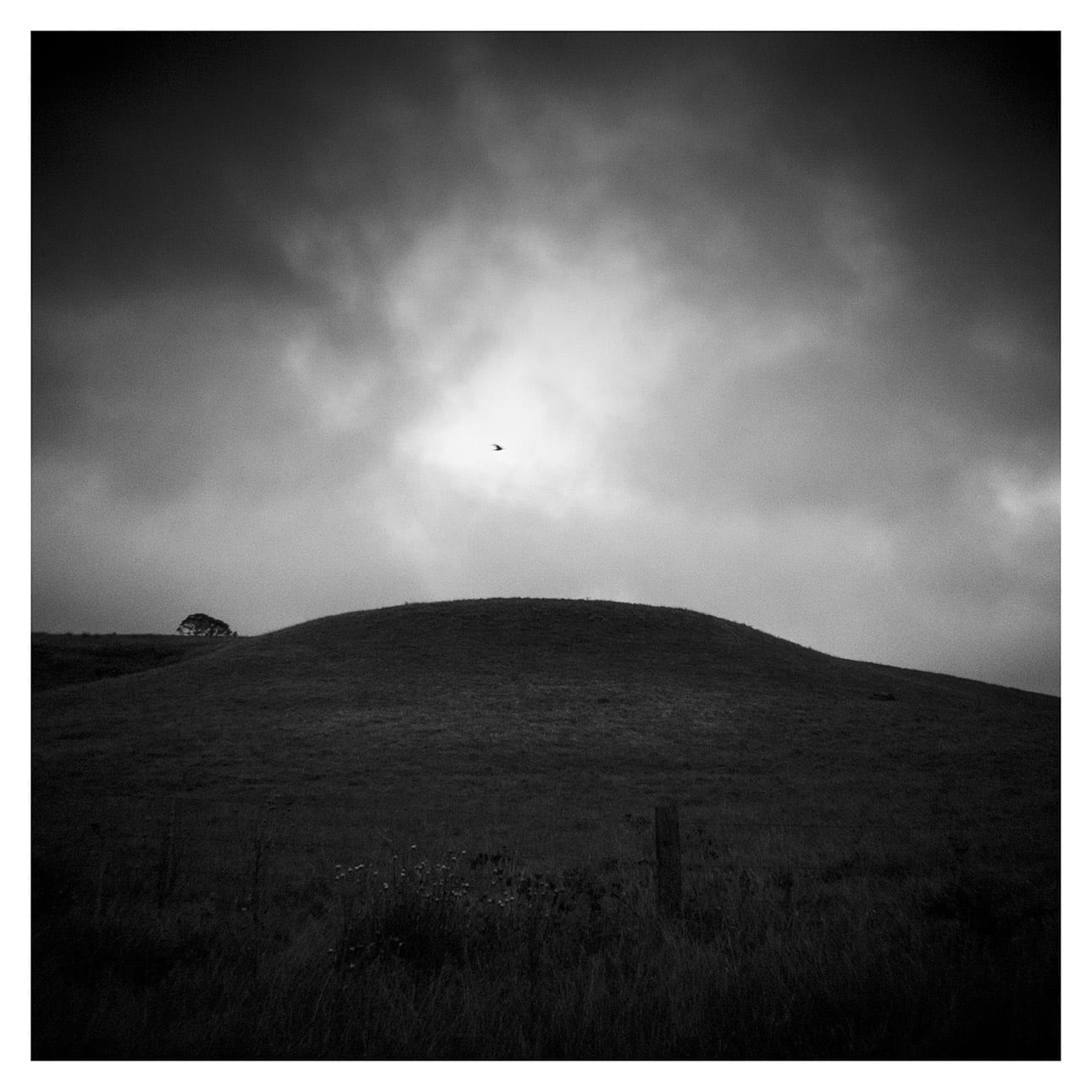

Originally from Australia, Sonia Mangiapane now lives and works in Holland. She approaches (the expanded field of) photography as a medium of light writing—over and above a medium of representation. Guided by her fascination with the physical properties and ethereal qualities of light she explores concepts of journey, place and notions of time. Mangiapane’s practice employs a range of camera-based and camera-less methods, producing a combination of representational and non-representational still and moving image works.

Emilie Poiret-Brown:

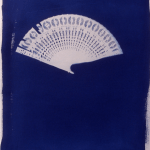

Emilie Poiret-Brown is based in South West of England. Her work lies on the boundary between photography and painting, it seeks to challenge the notions of what a photograph is and how it is created. With conventional photography, the artist’s intervention takes place off the surface. In contrast, painting is valued on the art- ist’s personal expression which takes place simultaneously with a physical interaction between artist and surface. The camera less process allows Poiret-Brown to interact directly with the surface and attempt to bring painting’s values to photography.

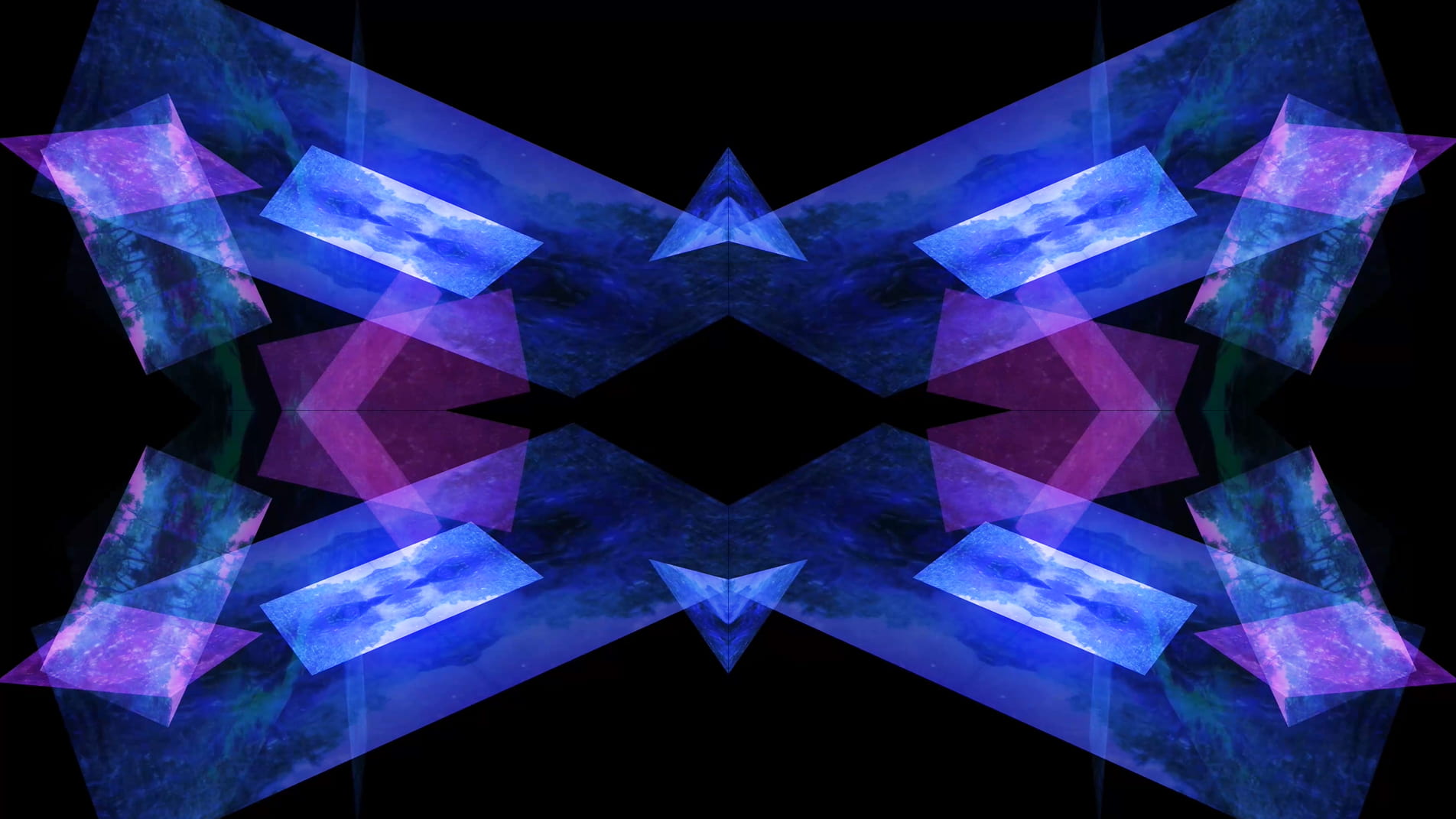

Megan Ringrose:

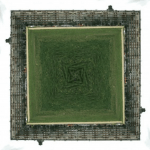

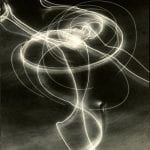

Megan Ringrose is photographic artist based in Oxfordshire in the United Kingdom. Her non-apparatus practice is grounded in research of the fundamental properties of photography: light, time, process, and materiality. Her practice is concerned with shifting photography away from its signifying function to explore and question traditional notions of the photographic medium. Ringrose defines her work as additive photographic abstractions linking the act of painting closely to my practice. She adds light and time to create photographic objects. She plays with long exposures and ways of slowing photographic processes in order to assemble the photographic works.

Erika G. Santos:

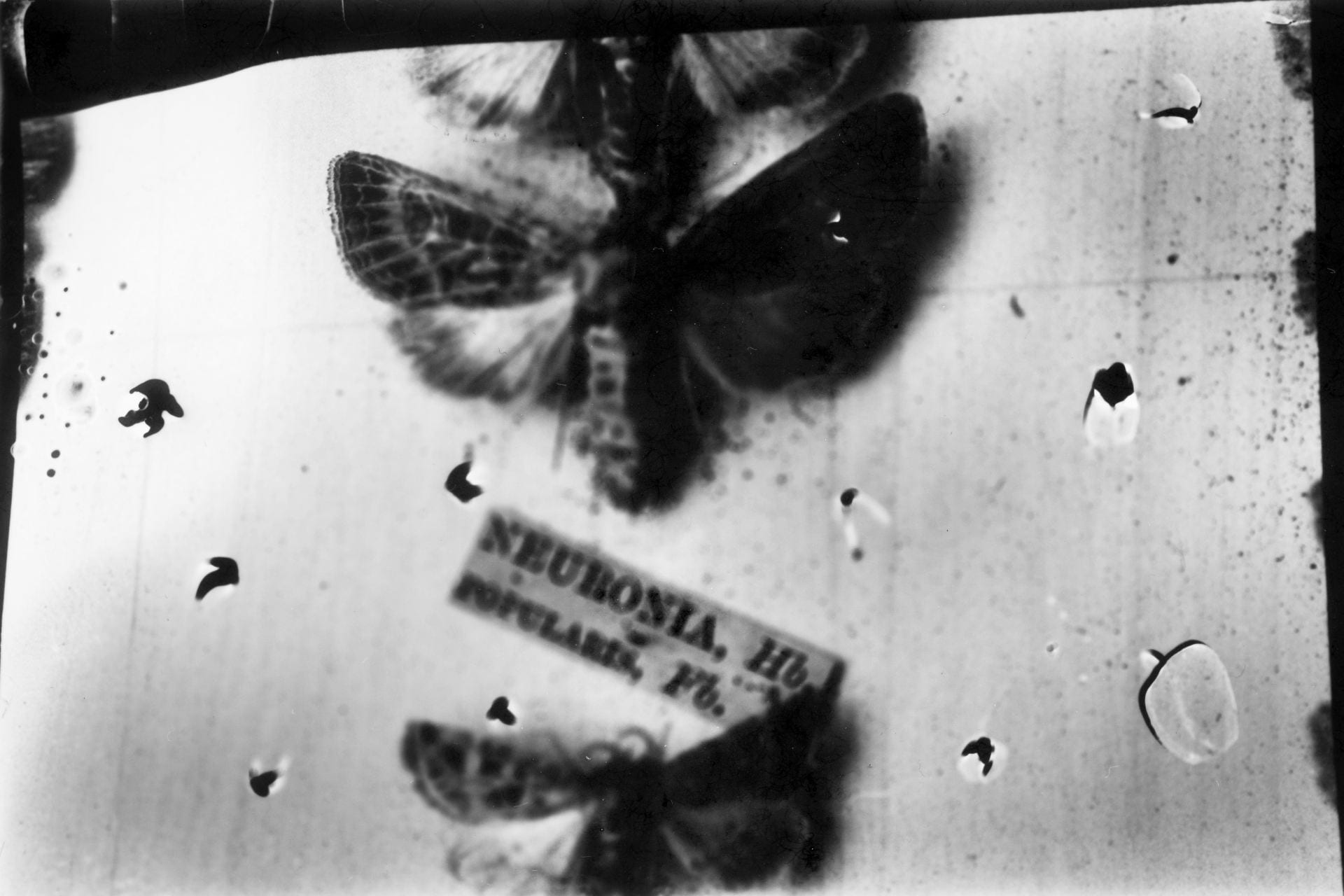

Erika G. Santos is based in Connecticut, United States of America. Santos works with photographic media to ‘dismantle’ or to take things apart, to use the pieces from destruction to rebuild and create something new and magical ,which in her own words, is the perfect way to define the human experience. Life is a series of birth and growth and rebirths. An endless cycle of positive and negatives. Santos takes this same approach with her photographic practice. She distresses her 35 mm negatives after they have been developed to create pieces of destructed and rebuilt beauty. This is a simulation of life and death, chemical paintings made to remind us that from fragments we can re-create and reassemble ourselves.

Kateryna Snizhko:

Kateryna Snizhko is based in Holland. Her practice posits photographic objecthood via the explicit merging of mediums, photographs and their derivatives. Snizhko explore photography’s potential to be metamorphosed with or into another form. Her goal is to provoke a deeper discussion by questioning: what is the photograph? when does the photograph stop being a photograph? When does an artwork arise in the process of creation? In her current series Debris Snizhko explores photographic waste and its transformation into other forms. She contemplates on the print recycling as an endless process of creation. Photography maintains the niche of the creative process far from the concept of solely image-making medium.

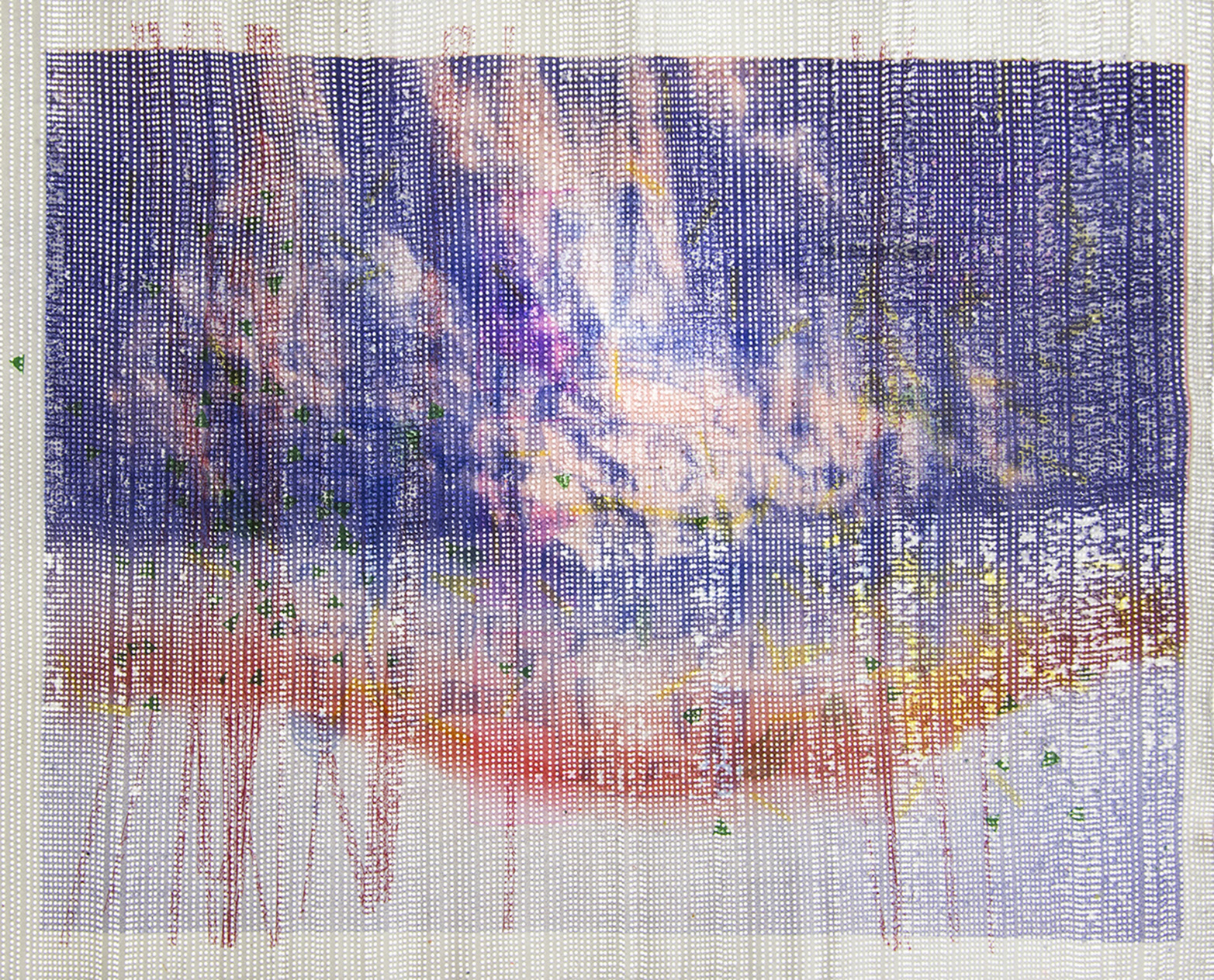

Lauren Spencer:

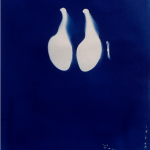

Lauren Spencer is based Rotterdam and the United Kingdom. The concept of I Dream of Screens is bound to its material and its process, with the work reflecting on the compulsive pull of the smartphone. In using analogue methods to re-make this portal into the digital world, the internet becomes something physical that can be controlled, paused to examine closely. The fleeting gestures of scrolling and swiping are distilled into a physical artefact, an analogue record of digital processes. In an experimental version of the photogram method, light-sensitive photographic paper used in traditional printing processes absorbs synthetic light from a smartphone screen, which is used to ‘paint’ or ‘stamp’ light onto the paper in the darkroom. This collage of ‘analogue screenshot’s is used to build the image of a device, a 1.5m tall slowed-down, smartphone- selfie.

Ellen Carey: Writes A Letter to the Artists

Light’s immateriality challenges its makers today, analogue versus digital, doubles our challenges. ‘What is a 21st century photograph?’ … and… ‘What does a 21st century

photograph look like?’ It is here, in the early stages of modern and contemporary art with its roots in photography, that this work has context.

At the dawn of photography, one finds the photogram. The word ‘photography’ means ‘drawing with light’ from its Greek roots; phōs for light, graphis for drawing. Originally

called ‘photogenic drawing’ later the ‘photogram’ a term that continues today, it was discovered by the British inventor, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) as a paper

negative print, contact printed for its positive. The photogram legacy continues under my darkroom practice Struck by Light (1992-2021). In colour, this history begins with

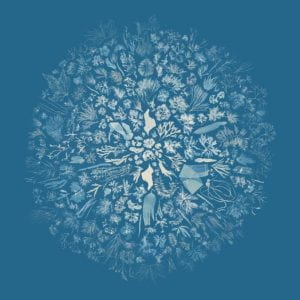

Victorian, Anna Atkins (1799-1871), Talbot’s contemporary, the first woman practitioner, also camera-less and the first woman in colour through the cyanotype, ‘sun pictures’

creating a Prussian blue, taught to her by Sir John Herschel, its inventor, a friend to both. Her photo-book pre-dates Talbot’s and her written words under her botanical

specimens, point to the future in ‘word art’. Anna Atkins has many firsts as a pioneer adding to the transformative power of colour embedded in her ‘light drawings’ one

sees – line-as-form in abstraction and minimalism, size and scale, edge tension, chaos and order, symmetry, asymmetry and much more.

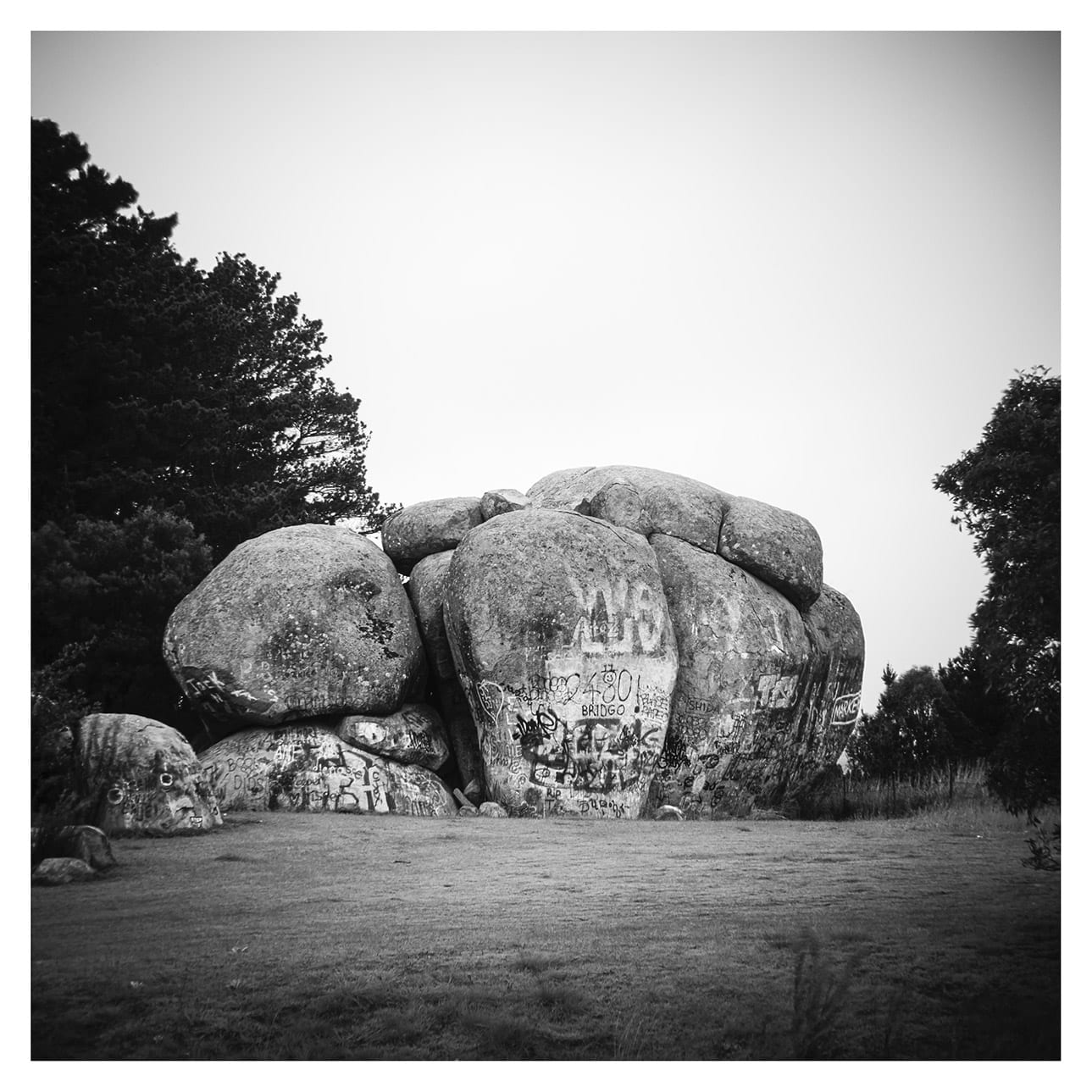

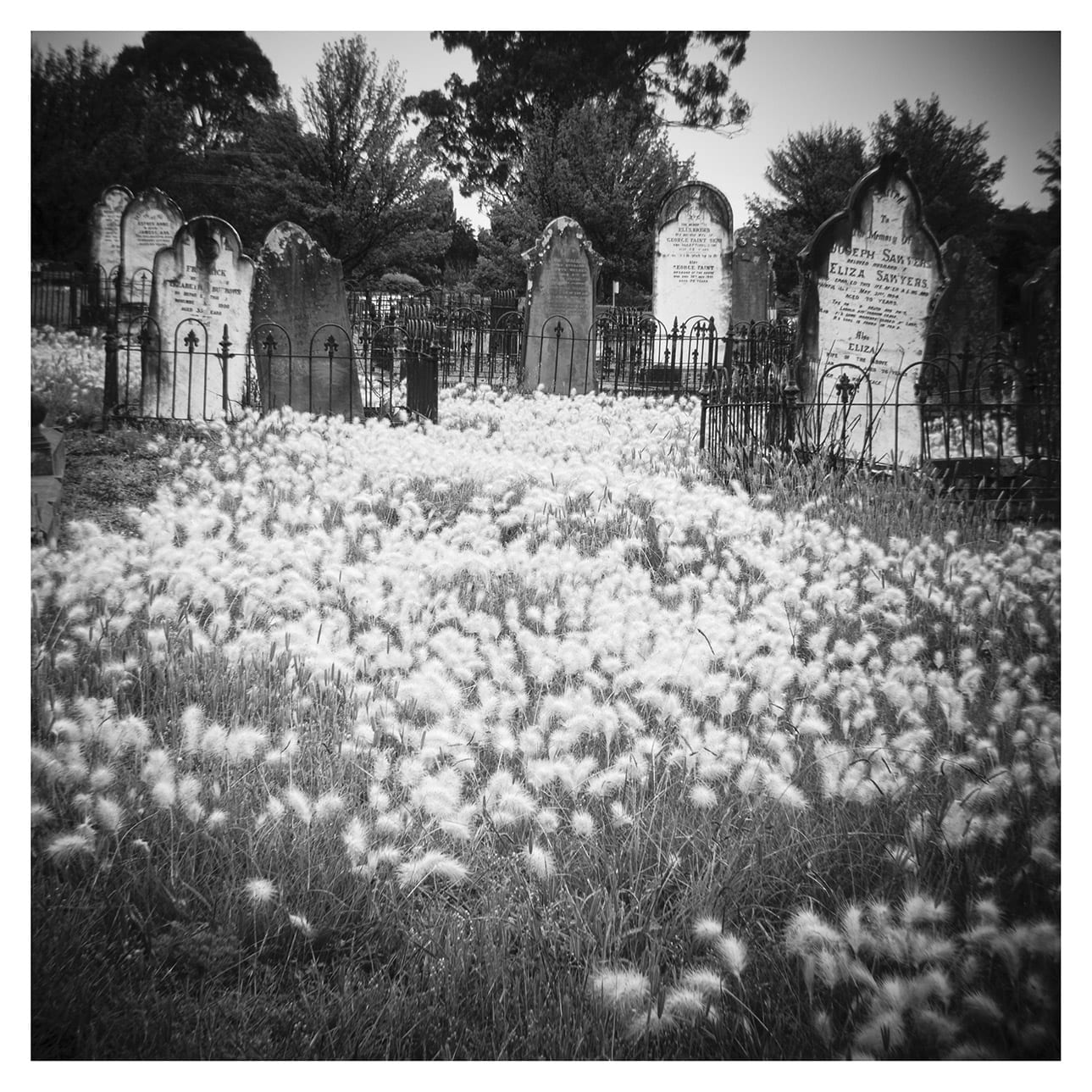

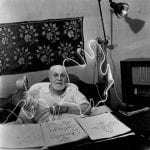

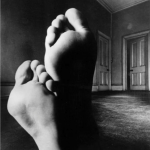

Nettie Edwards work recounts ‘her’ story, in a distinct approach, in her series Grave Goods both a record and document, a family snapshot, if you will. She highlights

the story of the ‘shadow’ as a memento mori, in a photographic tableaux and homage to a loved one, who recently passed away. Her visual diary, underscores the ‘shadow’

in art and photography, adding context, while content is seen through her experimental tableau vivant — here, in her work, I am reminded of the Greek fable as told by Pliny

the Elder: Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History (ca. 77 – 79 CE), relates the myth of art’s origin in a fable about the daughter of Butades, a Greek potter from Corinth. She

drew the outlined profile of her lover’s shadow as it was projected on the wall by a lamp, just before he left for battle, and which her father made into a sculptural relief. Thus,

before the real shadow departs with its owner it offers the young woman an image with which to represent her beloved — that which she fixes on the wall for all time. Sun

Pictures Catalogue (1)

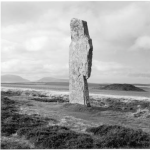

According to art historian, Victor I. Stoichita, in his remarkable book, A Short History of the Shadow (1997) (2) the hidden meaning of this myth involves the transcendence

of death. The image of the lover’s face on the wall is a vertical, erect, life-like projection, a figure. What is the daughter’s intent? To memorialise him? Give him life? Induce a

phantasm of foreplay when besieged so by the throes of Eros and Thanatos? We simply do not know. She seems to vanquish the threat of his death in war by making an

image that literally stands in for his absence — she makes him upright, that is, forever alive. Although the image she traced is only a spectre, it is, nonetheless, the immaterial

counterpart or double of the absent lover. It is not lost on us here in the 21st century that Butades’ daughter is nameless — a namelessness standing in for the fact of women’s

absence throughout art history, and a marker of women’s invisibility in language that ignores this one fact: the need to name the world is a human need. Nevertheless, the

daughter’s image remains. It is timeless.

1: Sun Pictures ‘Thirteen’. An exhibition catalogue. Text by Larry J. Schaaf, in association with Hans P. Kraus, Jr., (New York: Hans P. Kraus, Jr. Fine Photographs, 2004).

2: Victor I. Stoichita, A Short History of the Shadow, (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 1997).

(Excerpts: Donna Fleischer essay: “The Black Swans of Ellen Carey: Of Necessary Poetic Realities” from the exhibition catalogue: ‘Let There Be Light: The Black Swans of Ellen Carey’ from her one person exhibit at Akus Gallery, Eastern Connecticut state University (ECSU). January – February 2014 ( www.ellencareyphotography.com)