GlenN Porter

Glenn Porter first studied photography at the Sydney Institute of Technology and has a mix of art, science and photography qualifications. He also holds several postgraduate qualifications including a Graduate Diploma in Science from Sydney University, Masters of Applied Science (Photography) from RMIT University and a PhD in Communication Arts from Western Sydney University. Glenn has also been recognised by the Royal Photographic Society with an imaging science distinction as an Accredited Senior Imaging Scientist (ASIS) and a Fellow (FRPS) of the society. He is currently studying on the MA Photography at Falmouth University. Glenn has exhibited his work in several group exhibitions and has his first solo show in China in 2022. Glenn’s work has been recognised in several prestigious awards as finalist including the Head On Portrait Prize, the Olive Cotton Award for Photographic Portraiture and the Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize.

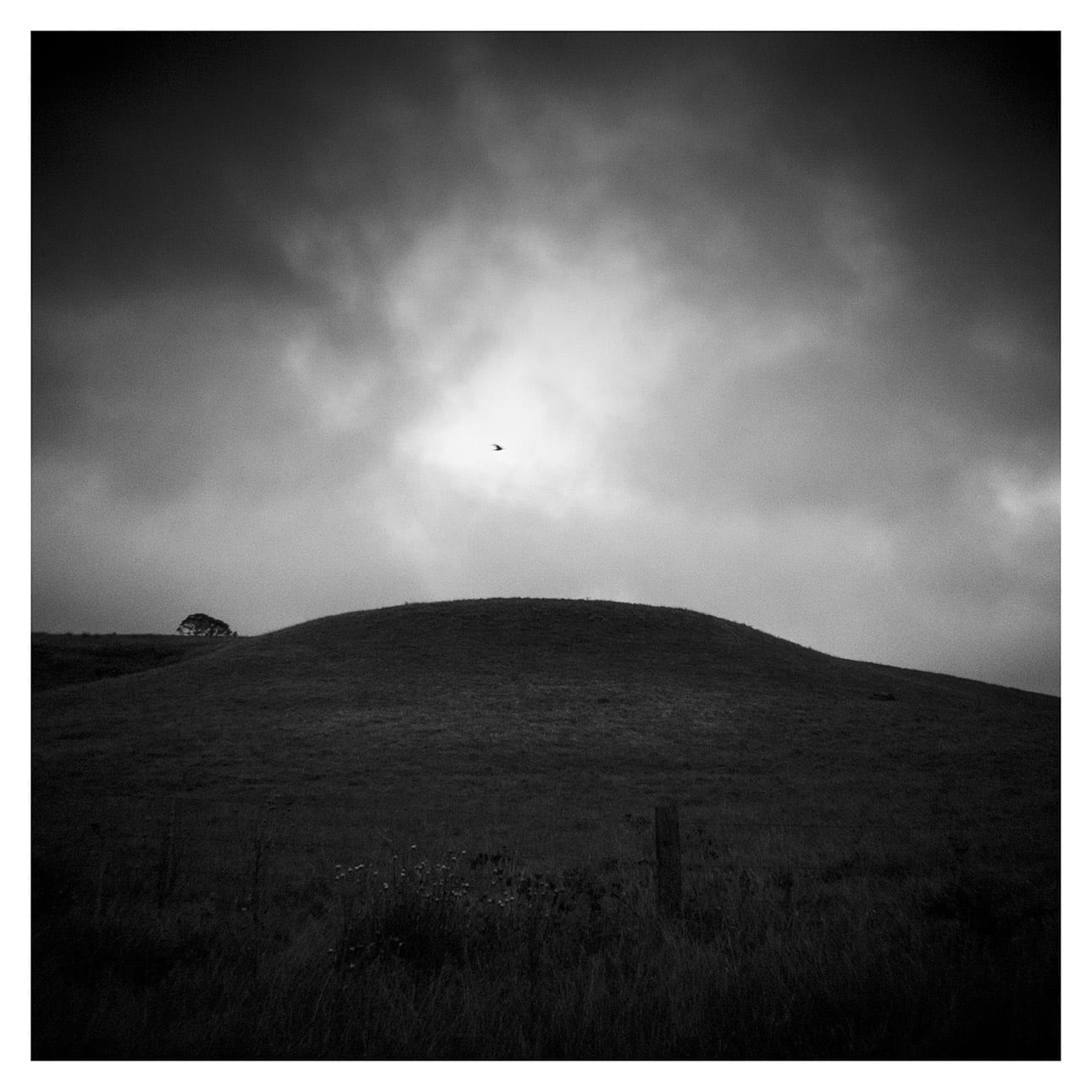

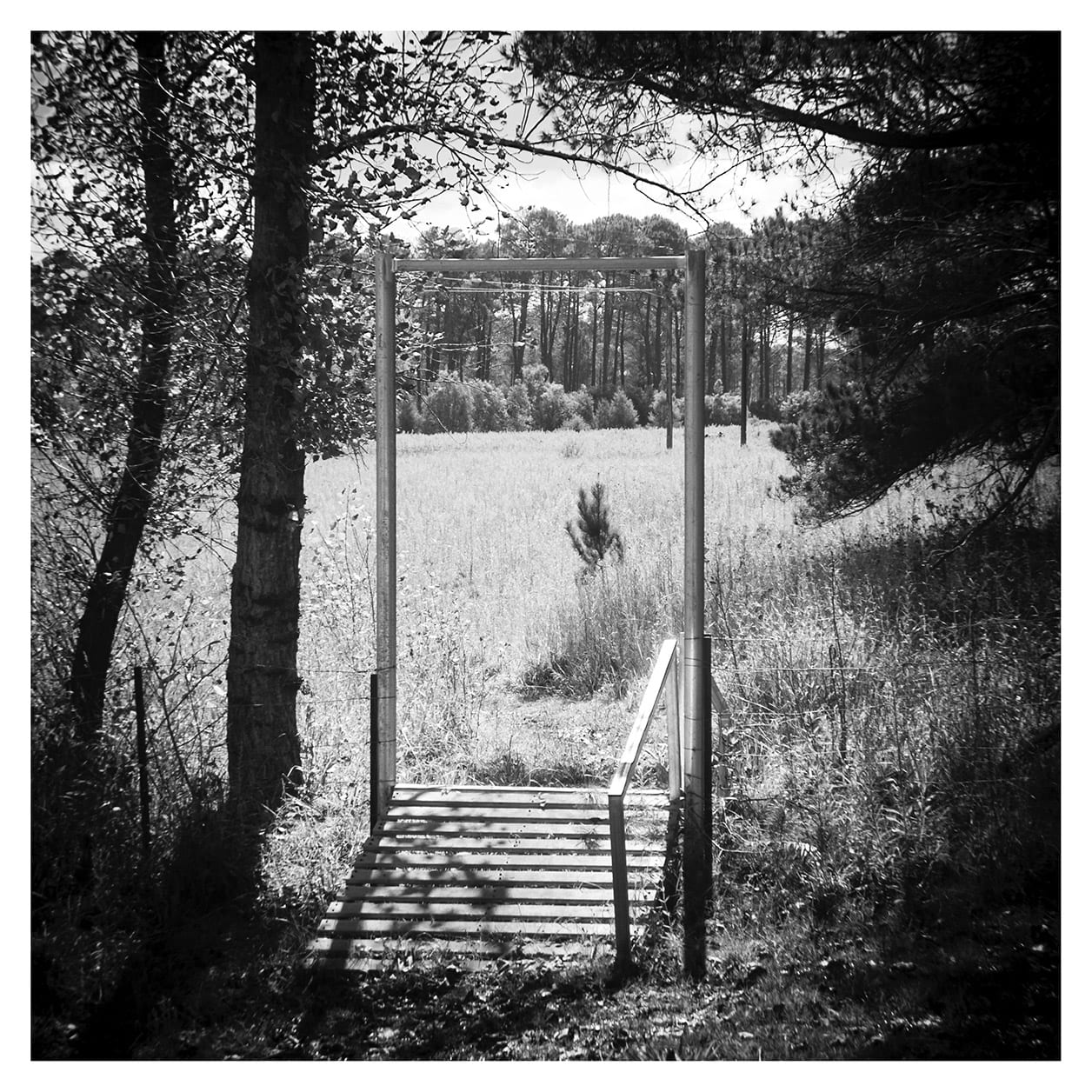

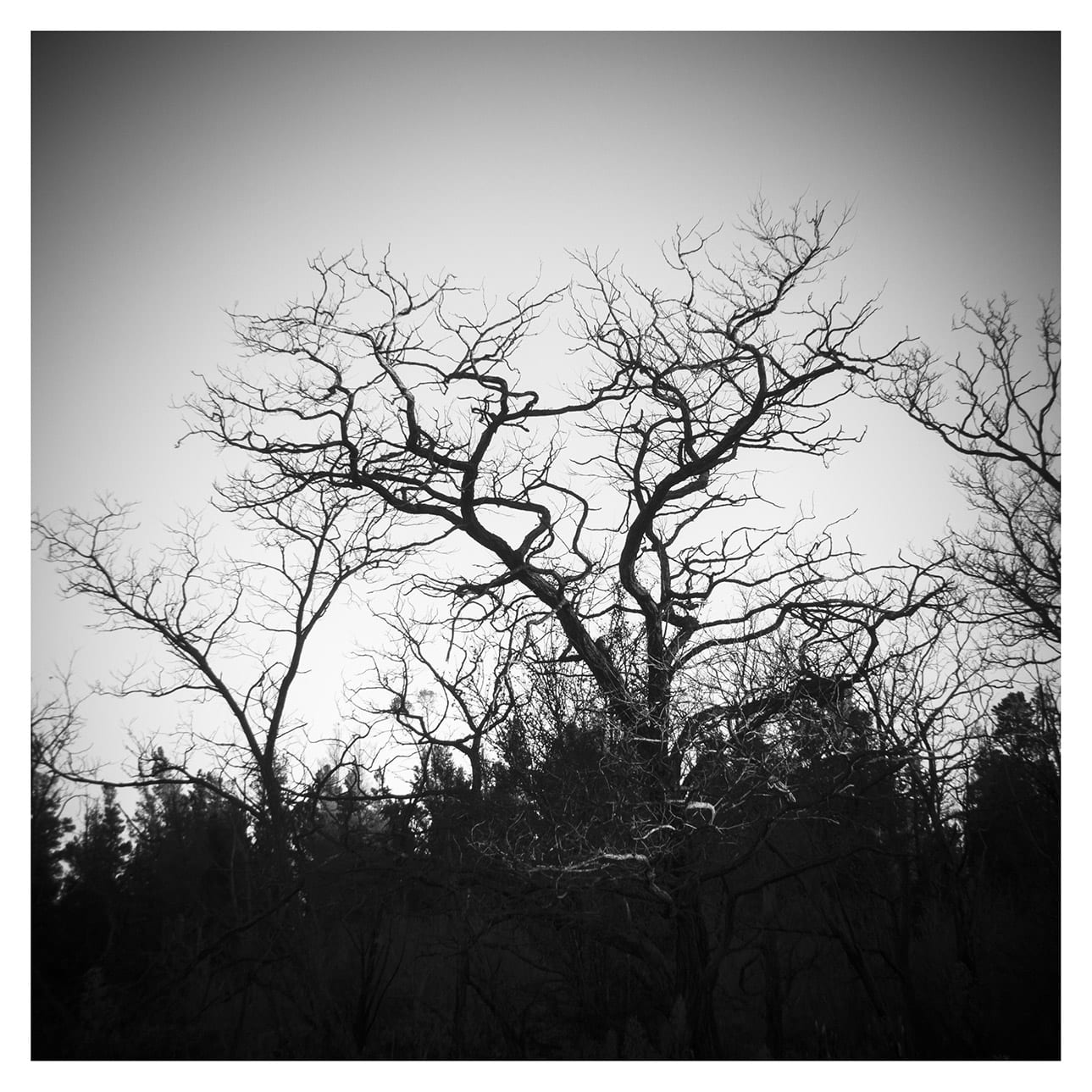

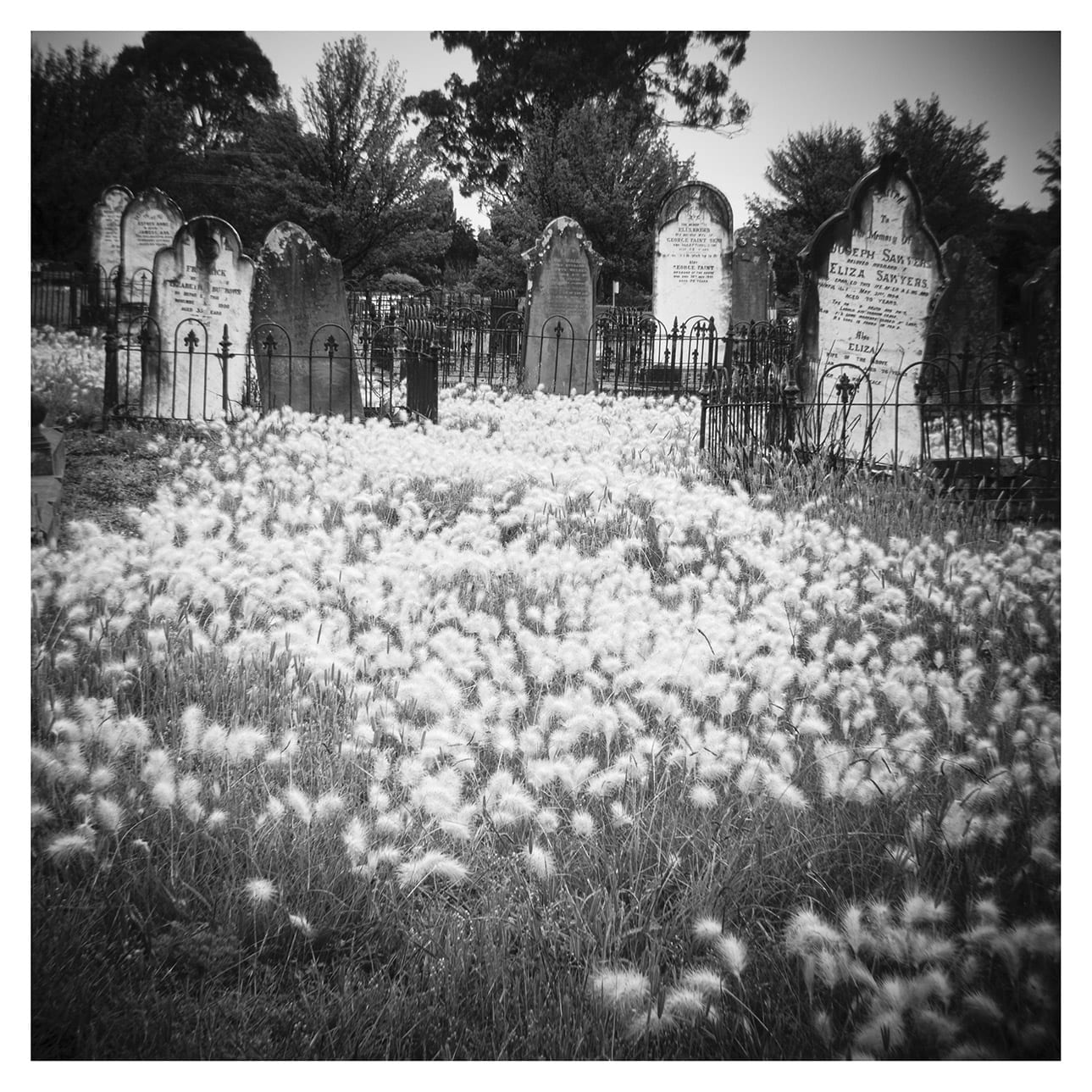

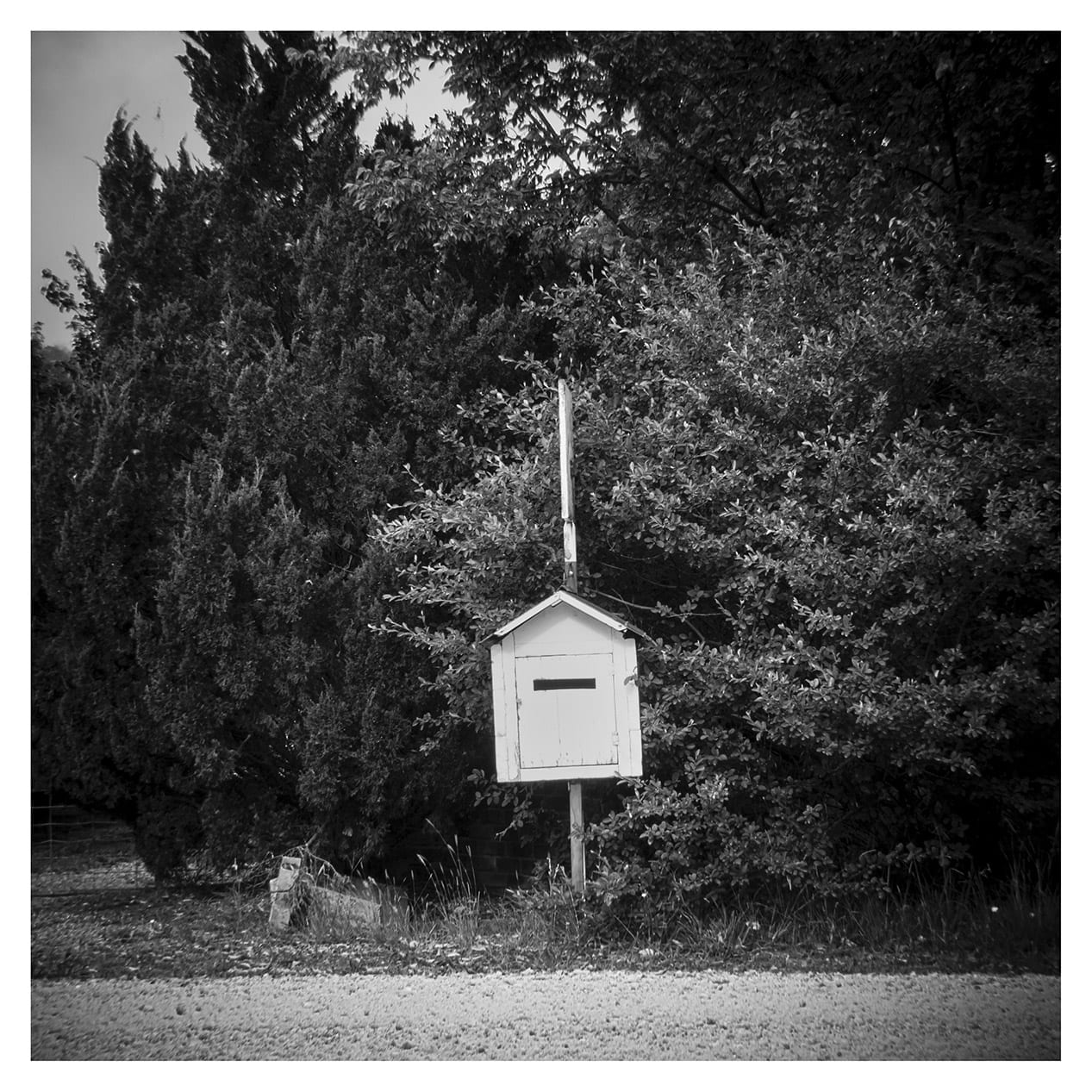

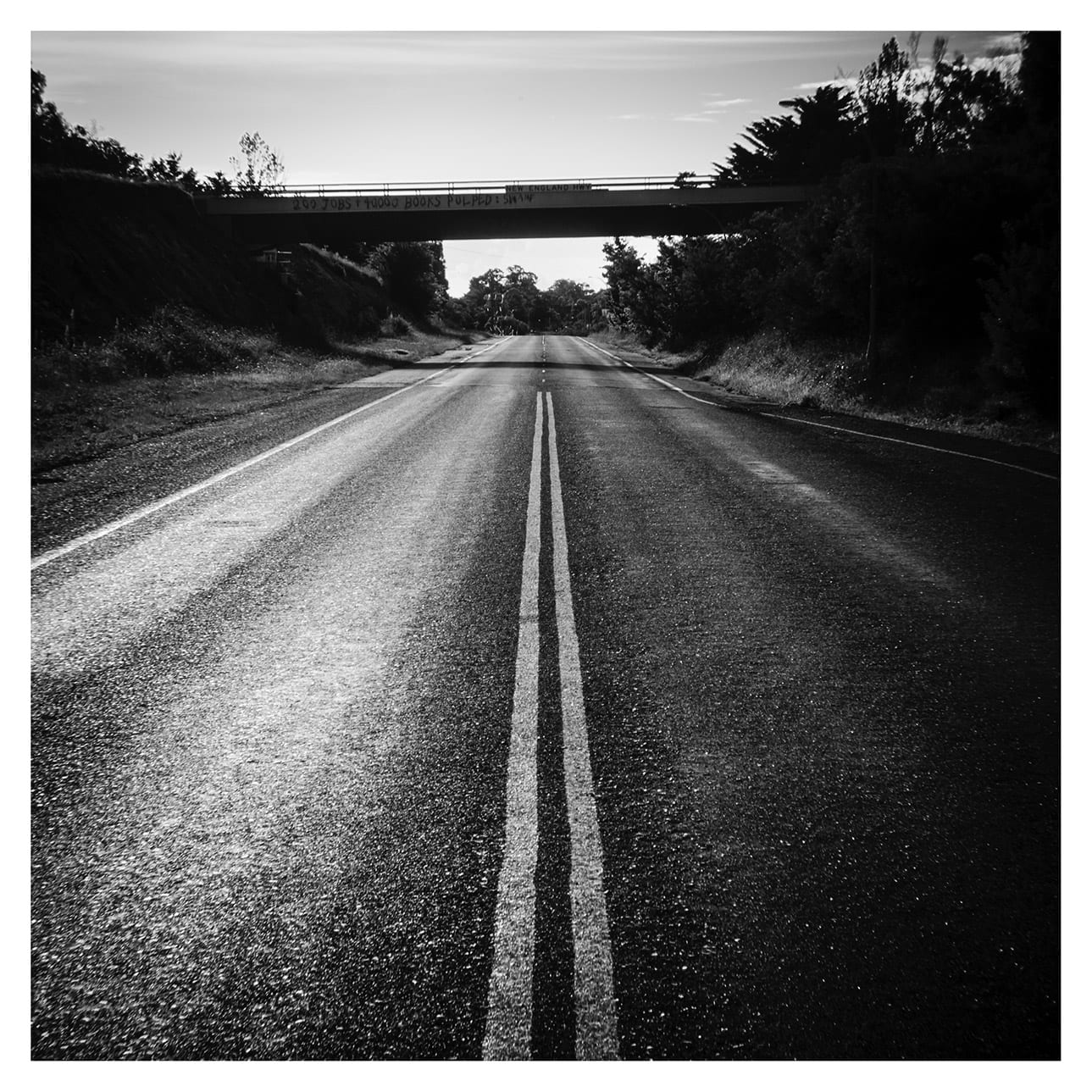

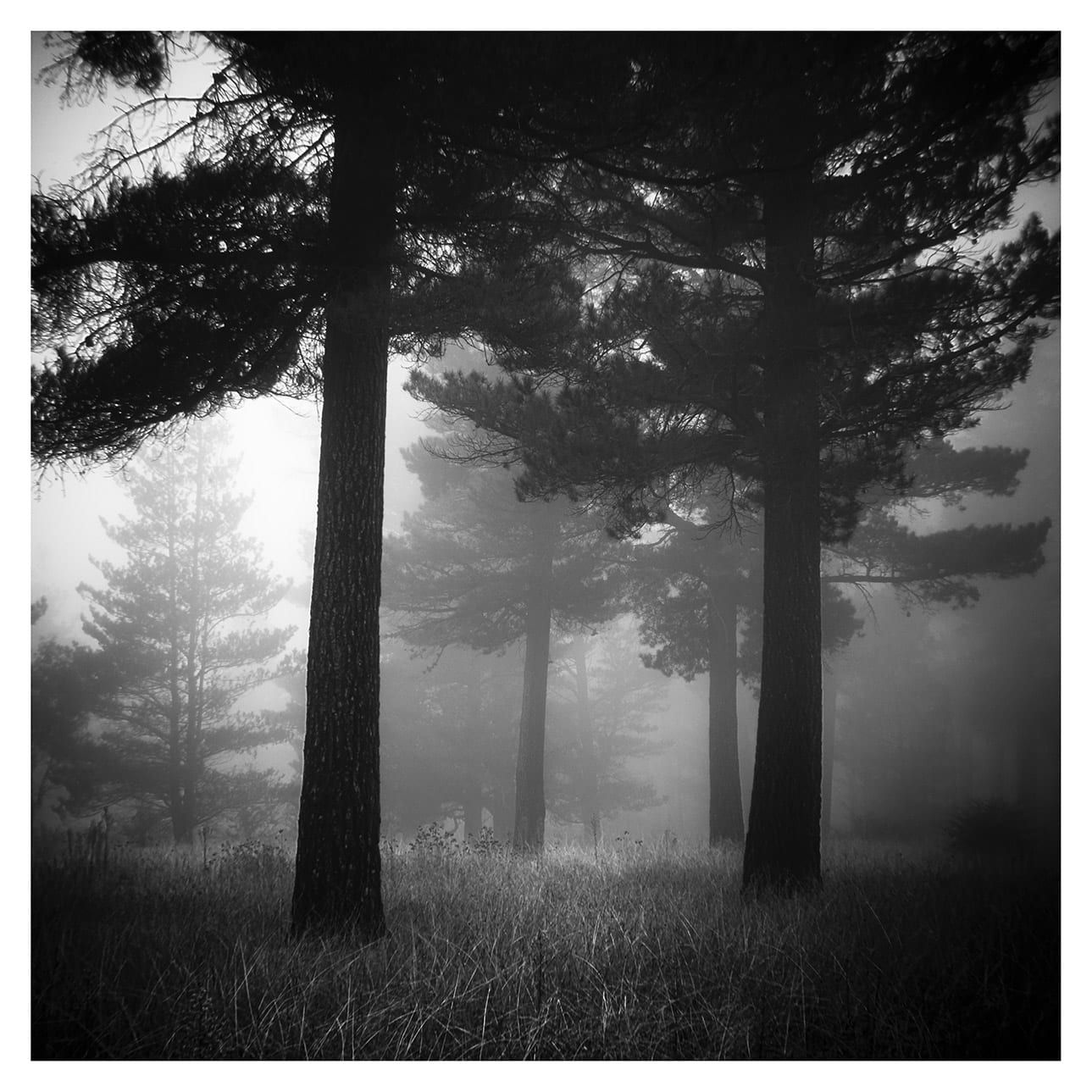

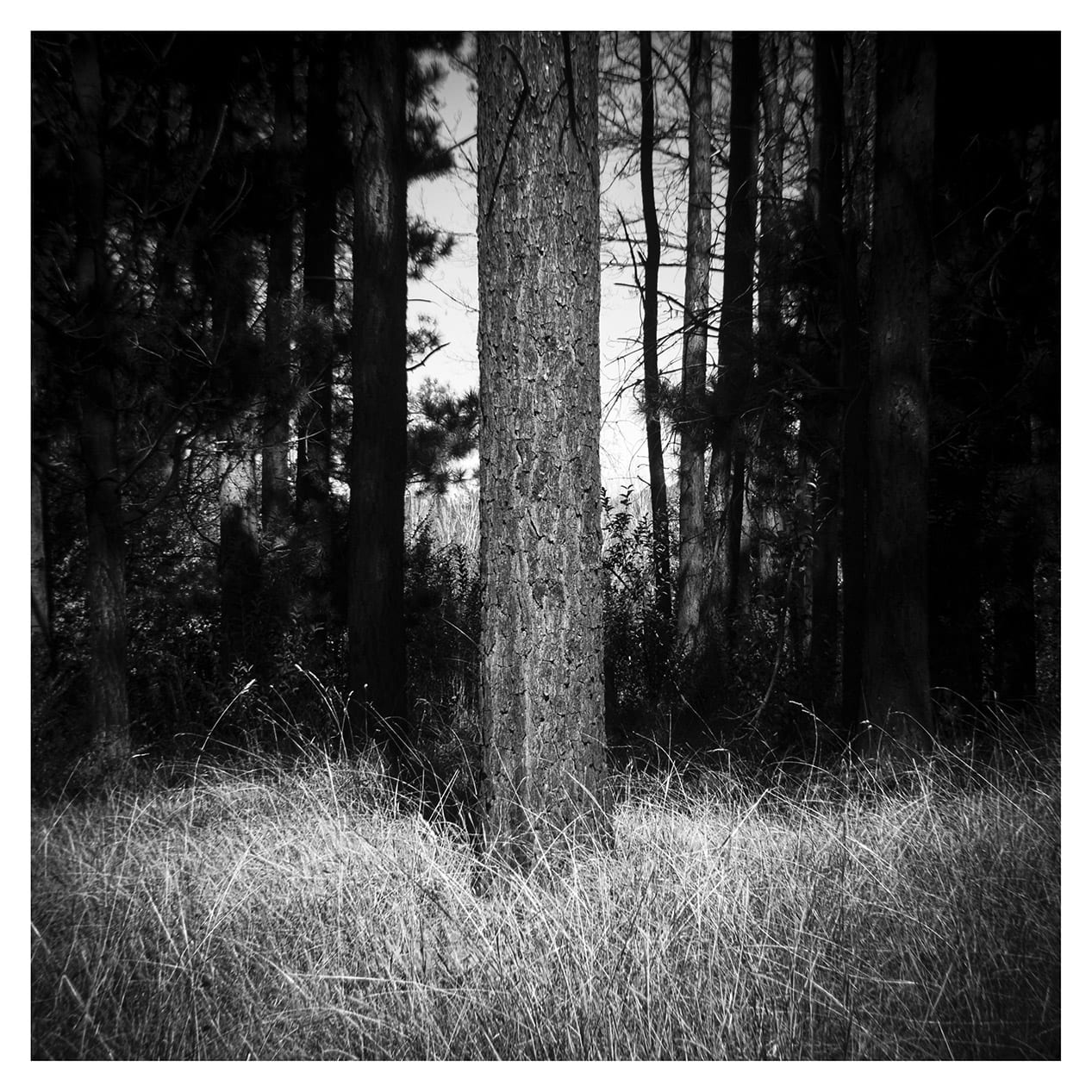

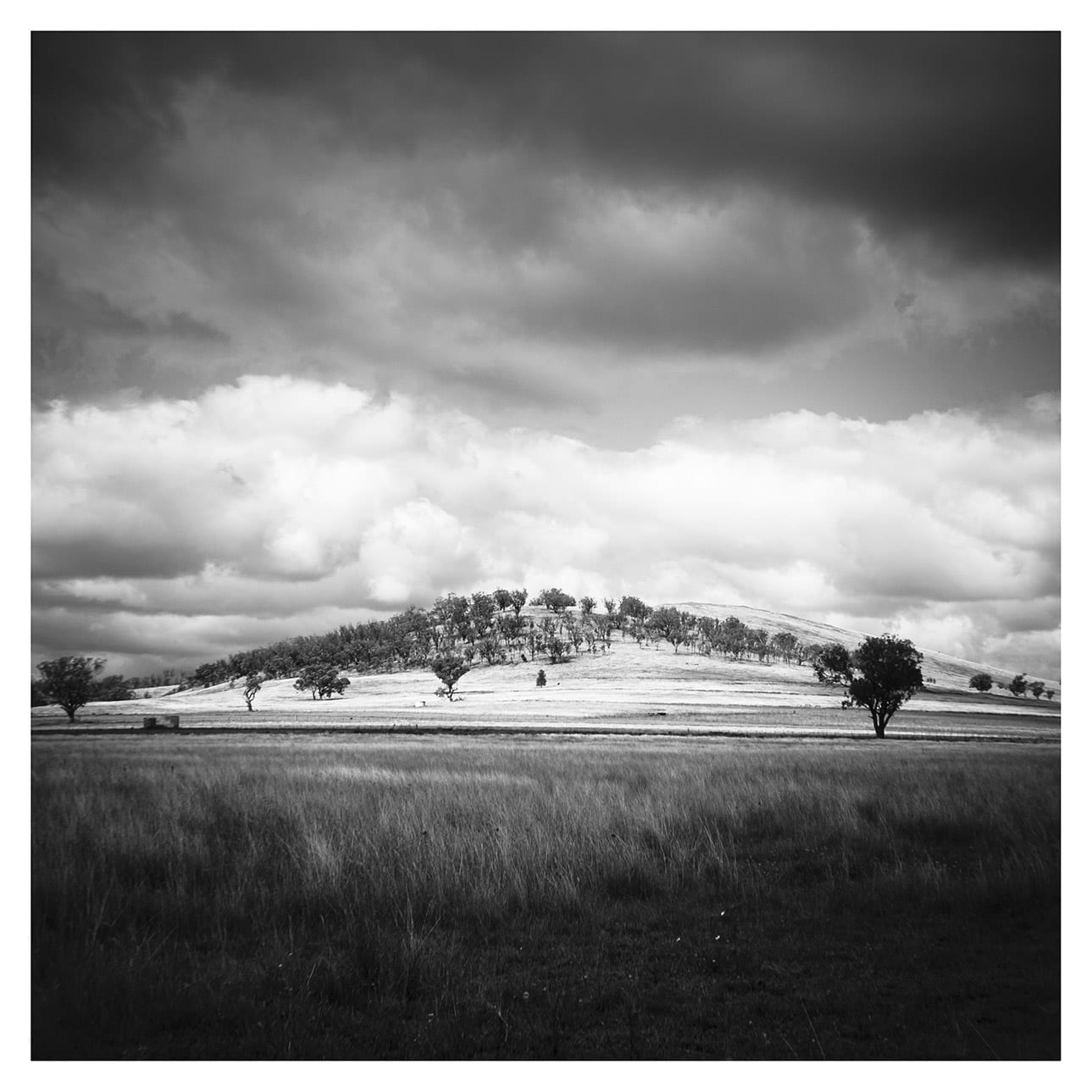

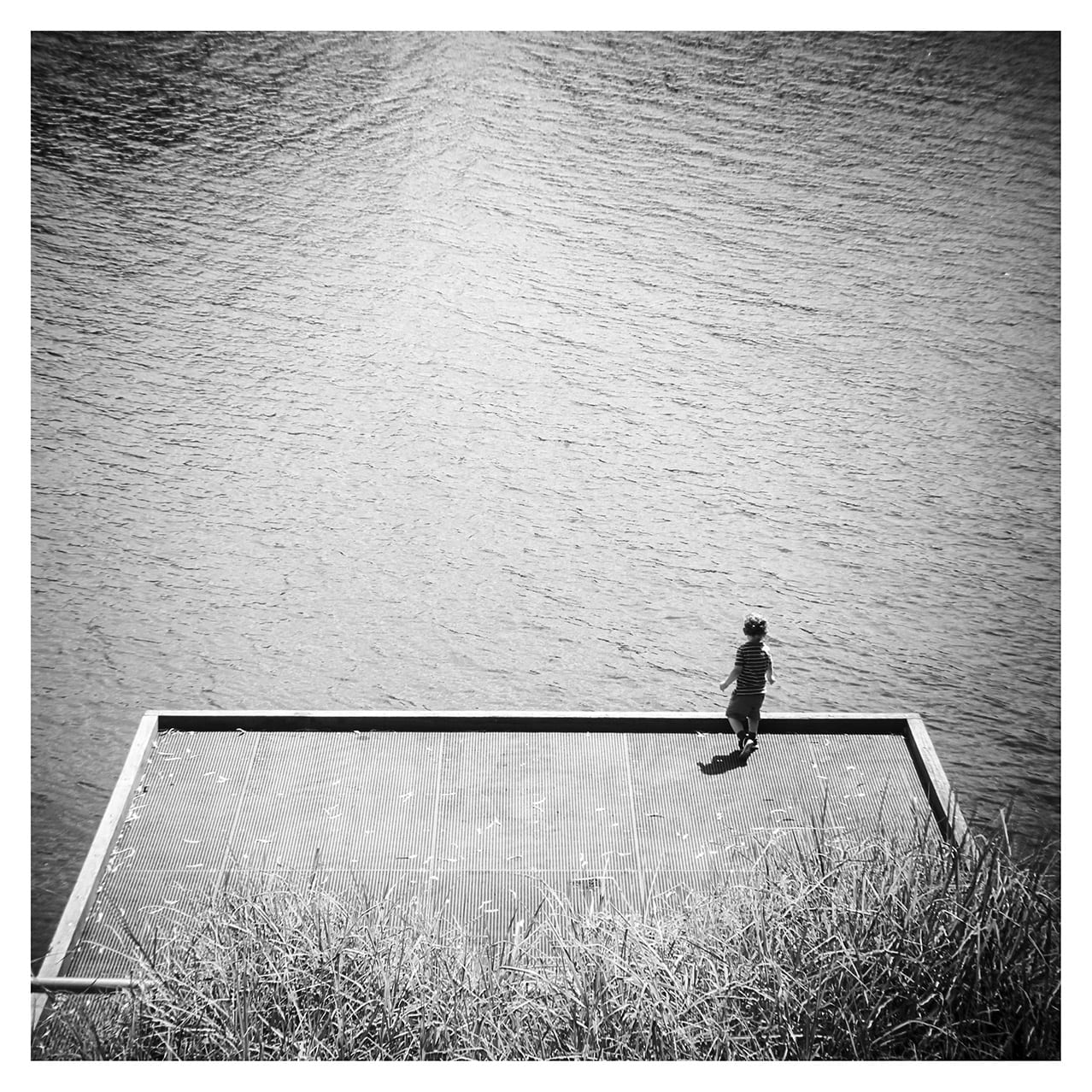

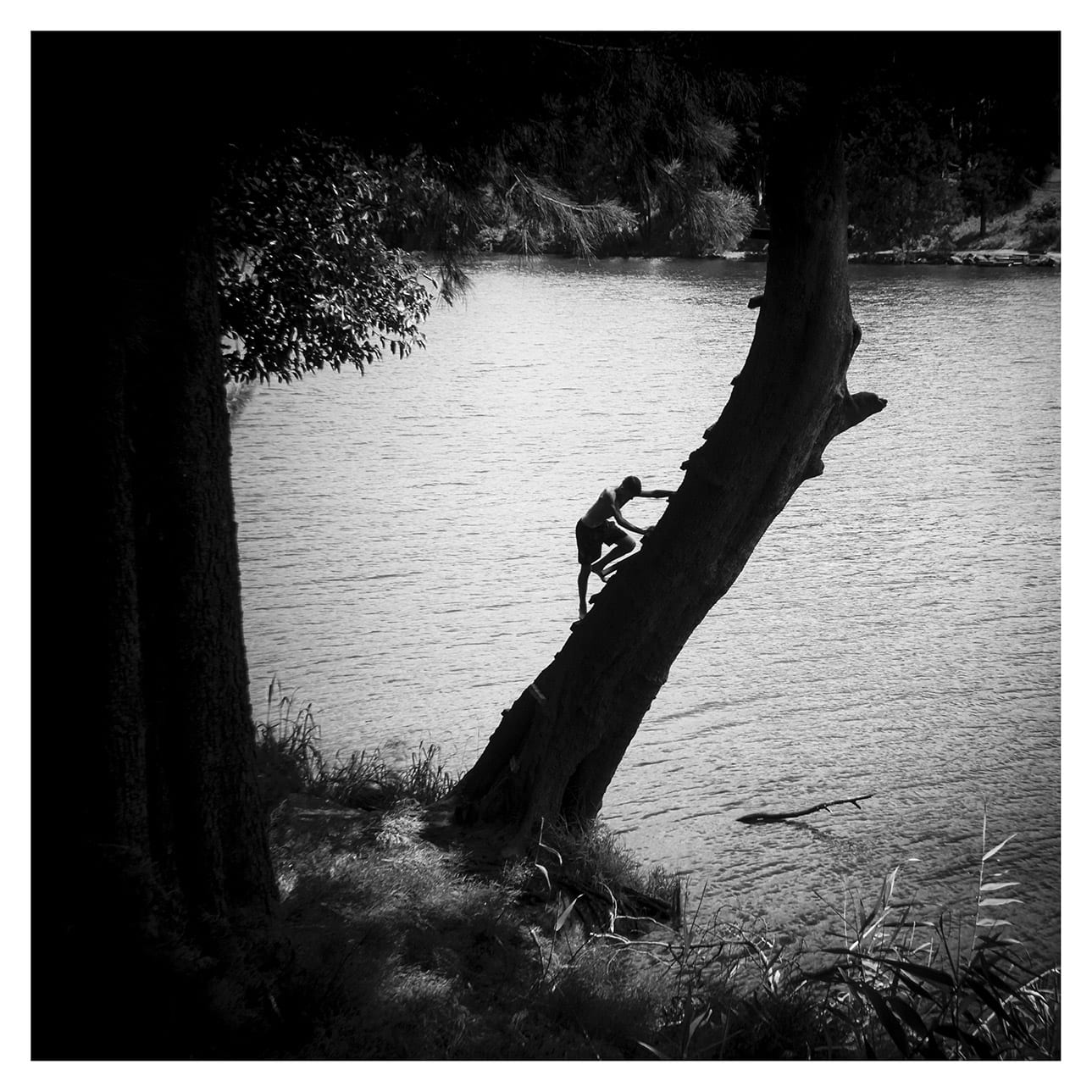

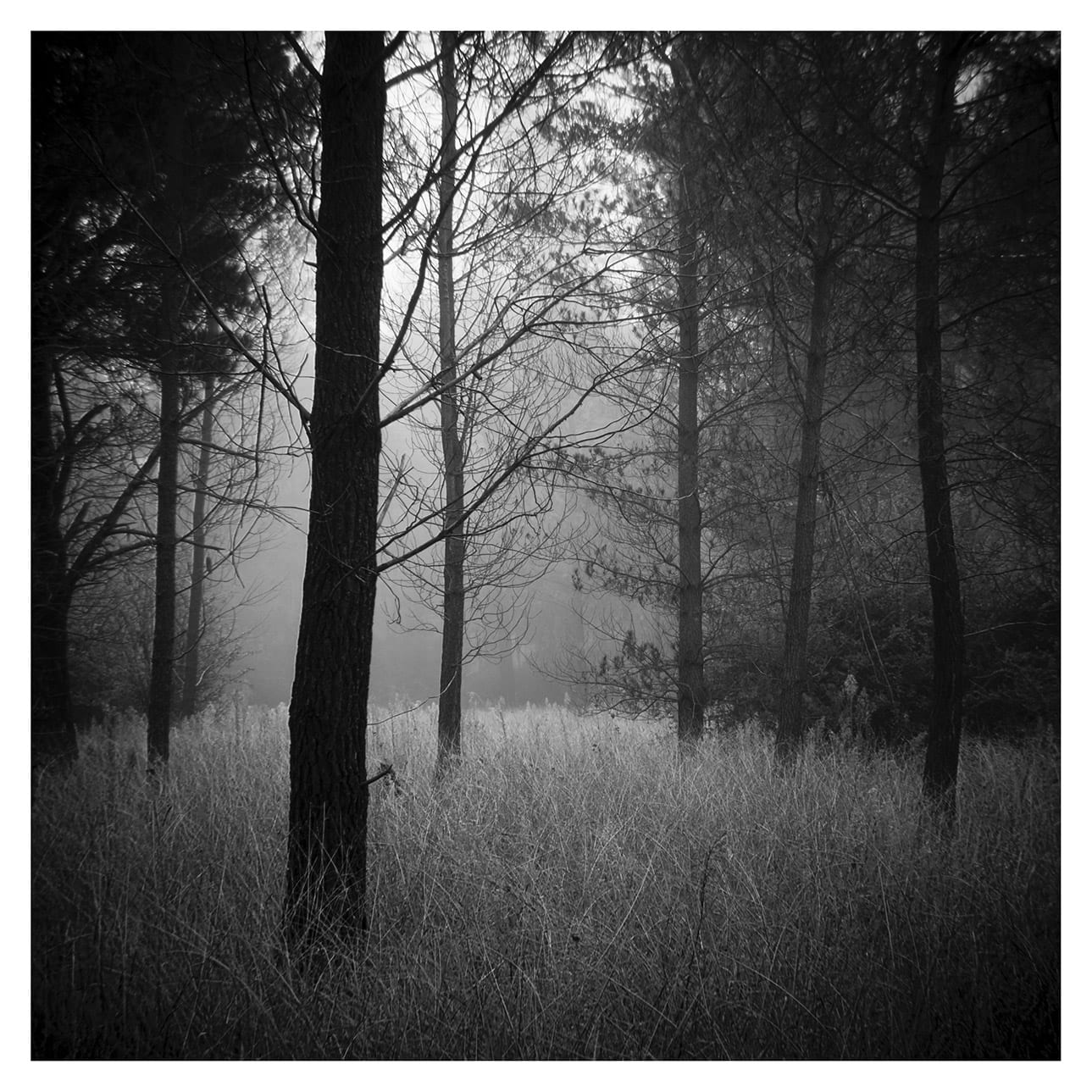

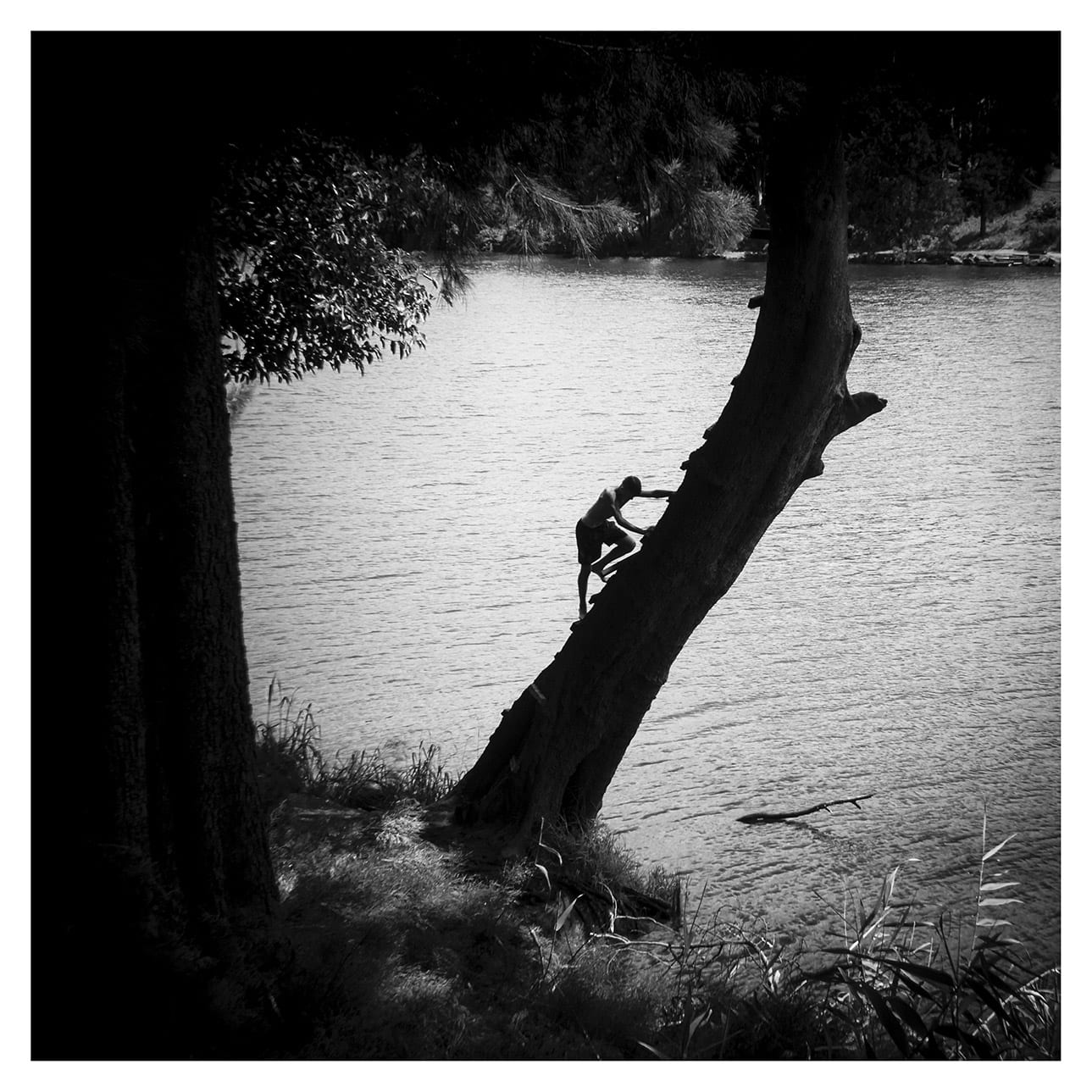

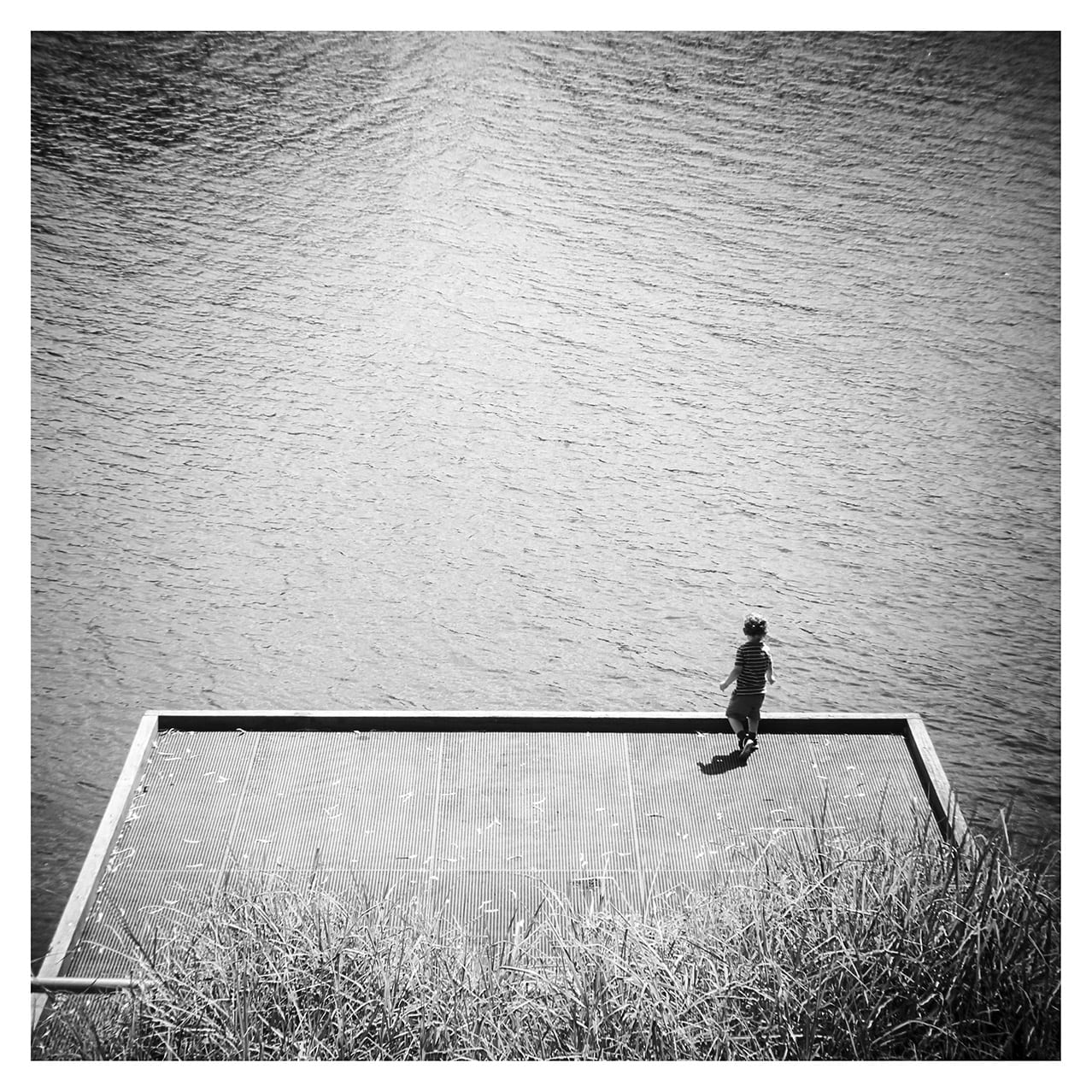

The Holga Experiment began as a method of approaching photography from a more instinctive position and being free from technical equipment and fixed ideas about content. It was initially an experiment in opening up my awareness to the environment around me and to shift my photographic vision from being a farmer to a hunter of images – moving out of the studio and into the world with just a single lens and camera. The simplification of the approach to my photography was liberating and the work began to get stronger as I became comfortable about shooting by feeling rather than planning. Henri Cartier-Bresson suggested “Technique is important only insofar as you must master it in order to communicate what you see. Your own personal technique has to be created and adapted solely in order to make your vision effective on film” (Cartier-Bresson 1999). Cartier-Bresson also applied a simplistic approach to his photography using the same camera format and focal length lens with the majority of his work. Keeping the method simple, allowed me to explore the purpose of the work from an internal perspective and to develop my work more intuitively.

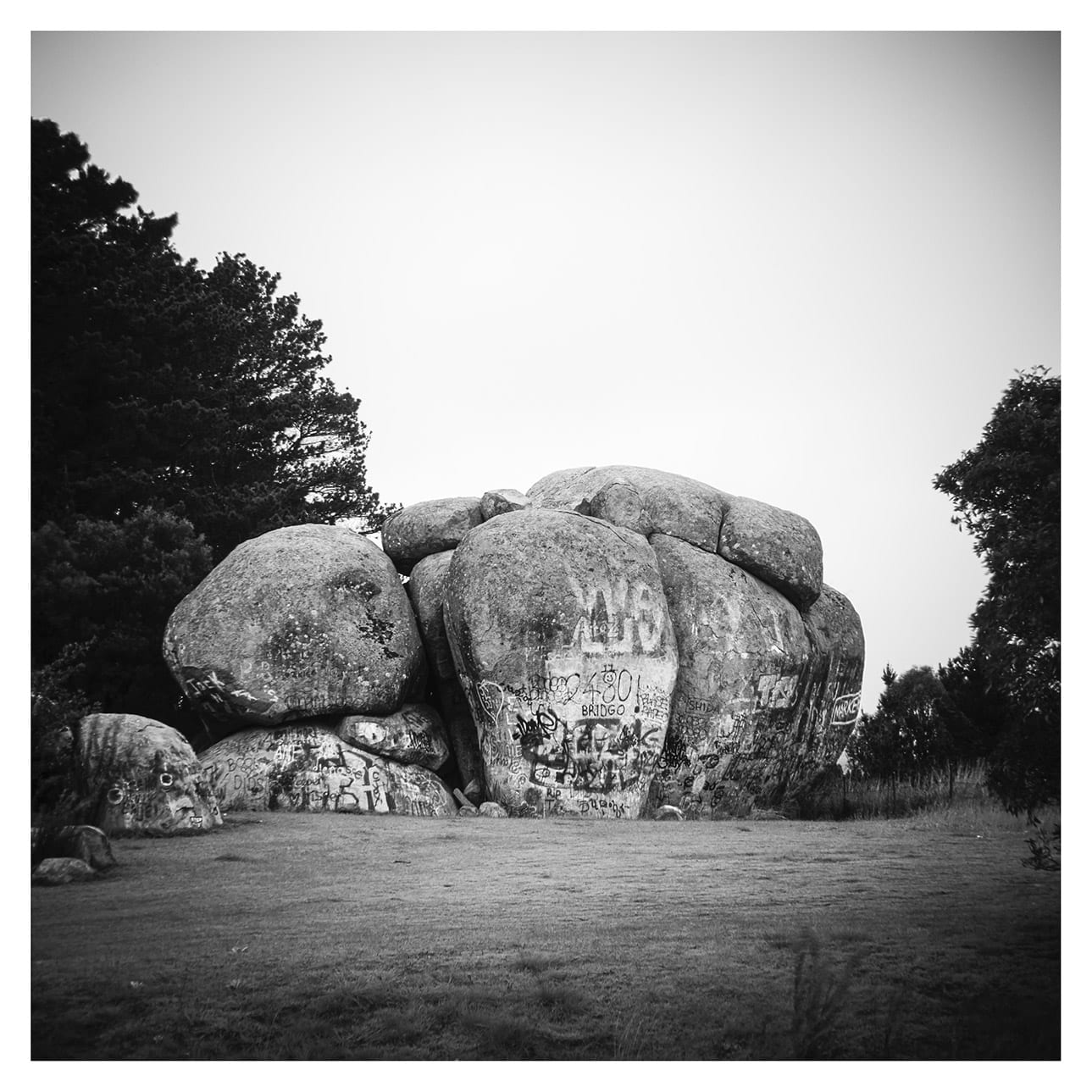

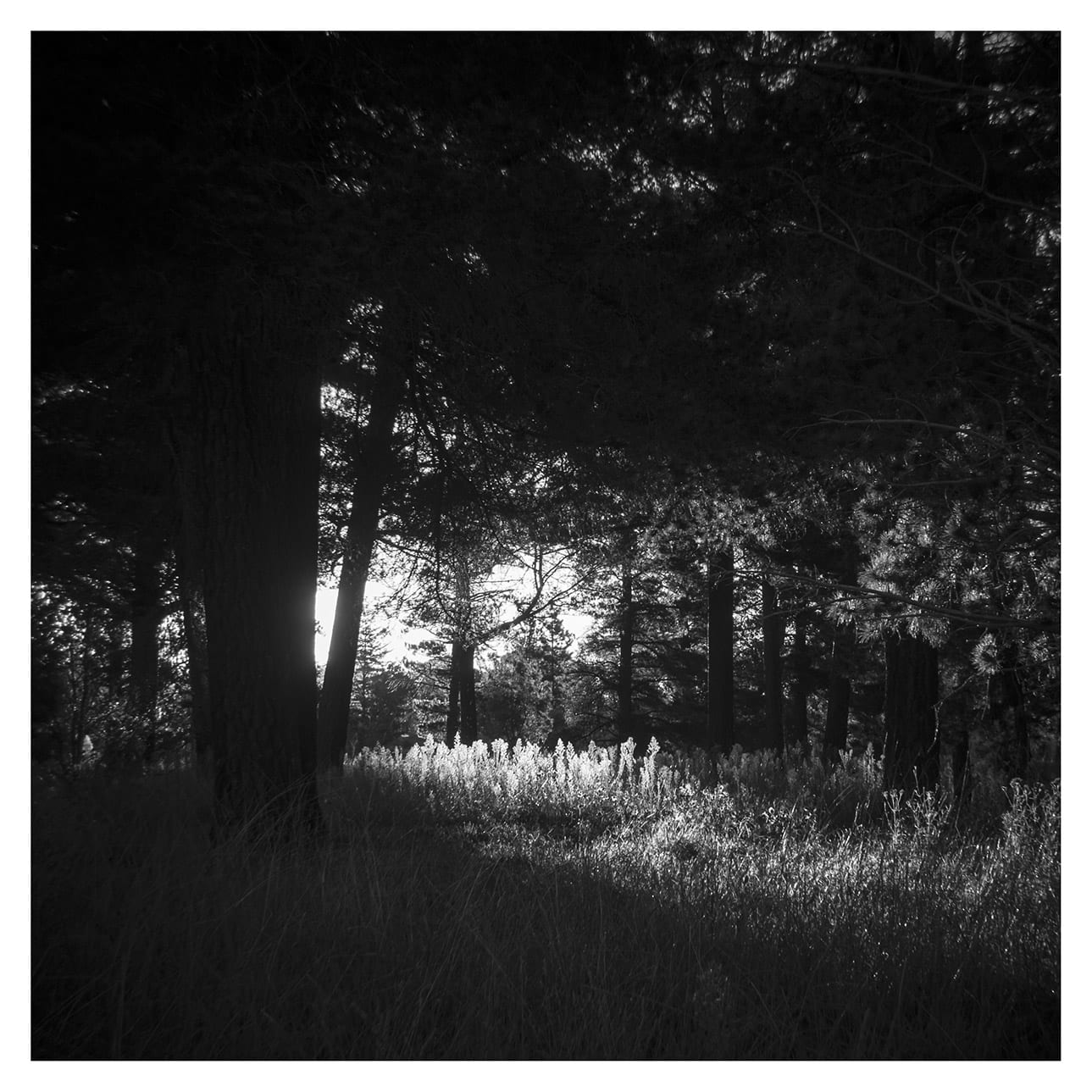

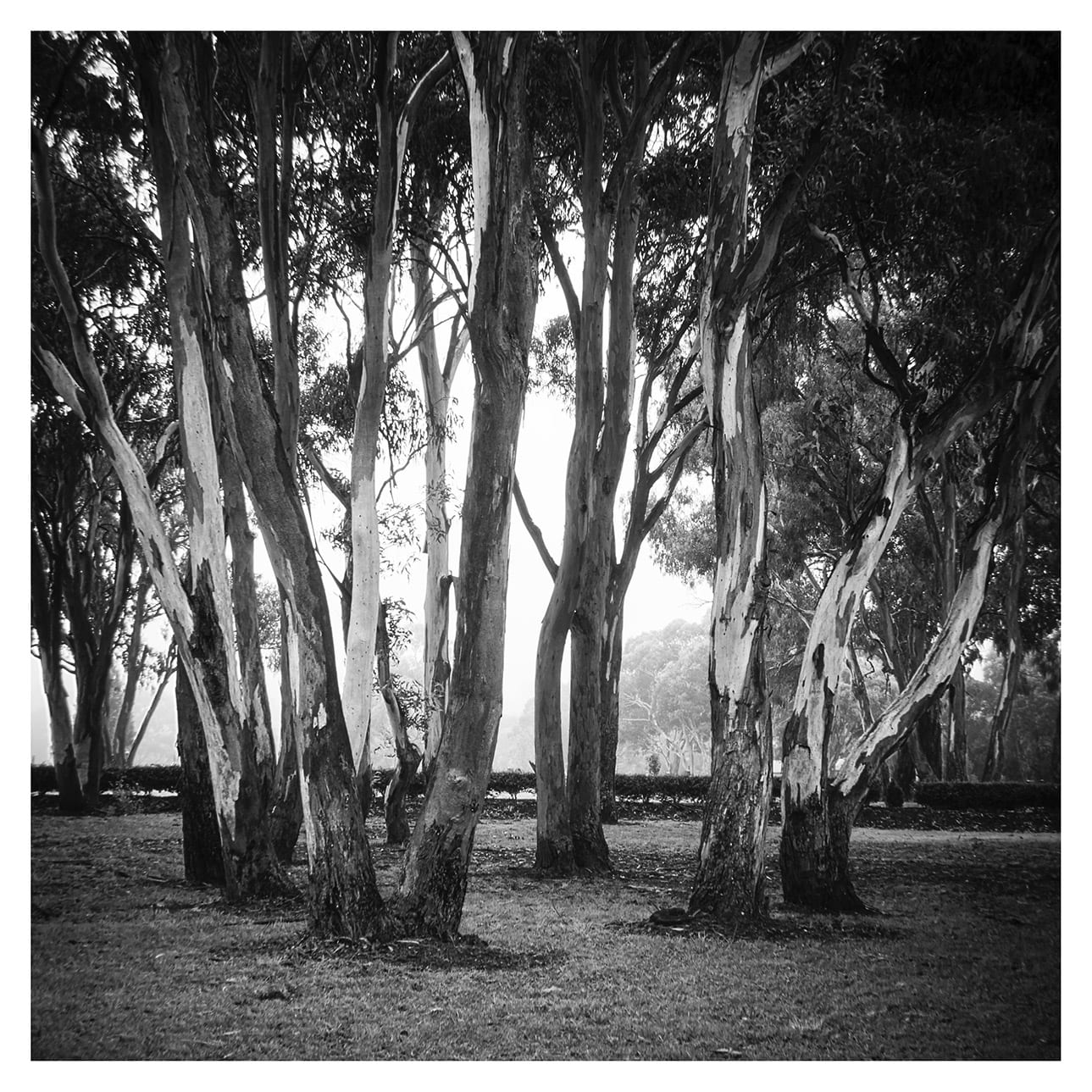

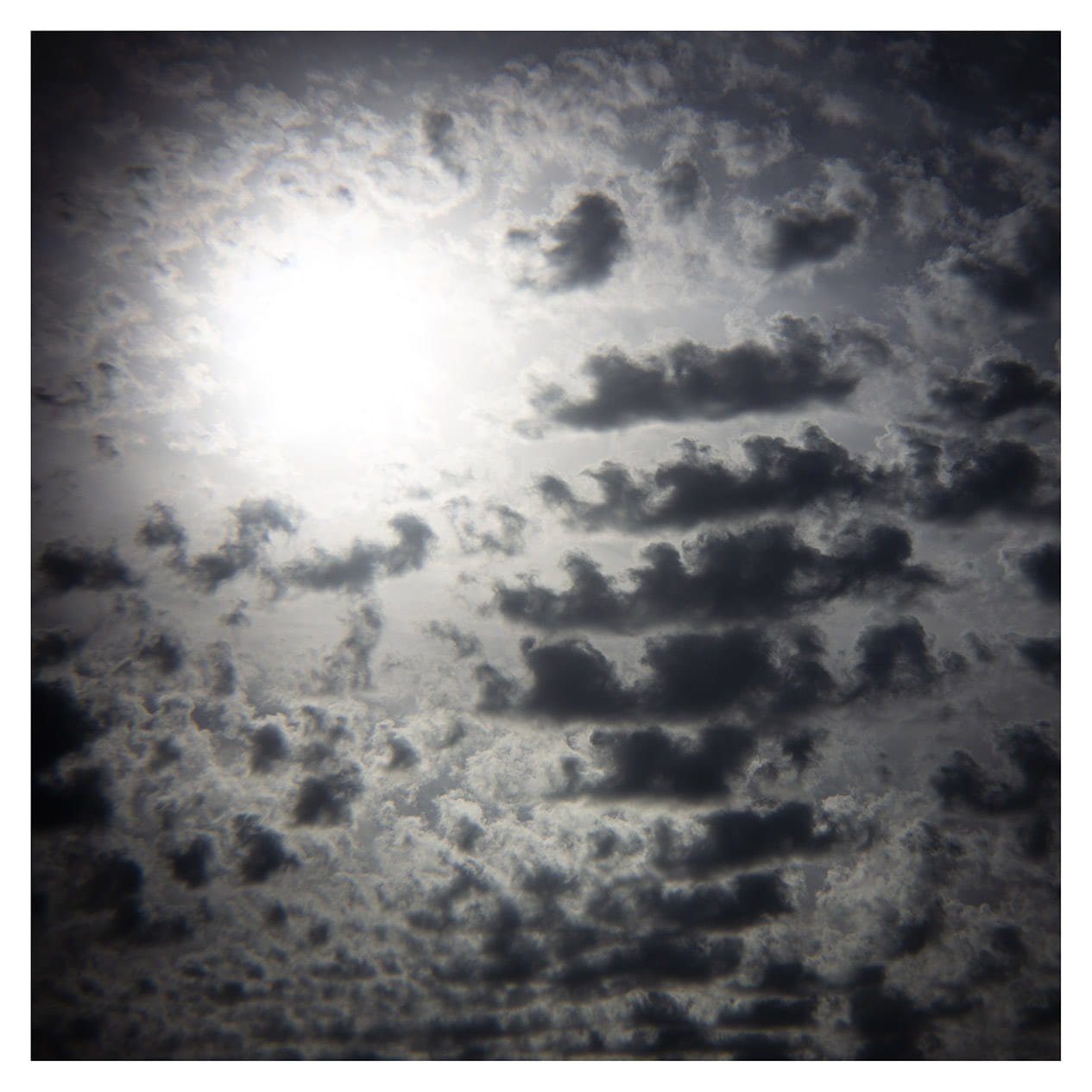

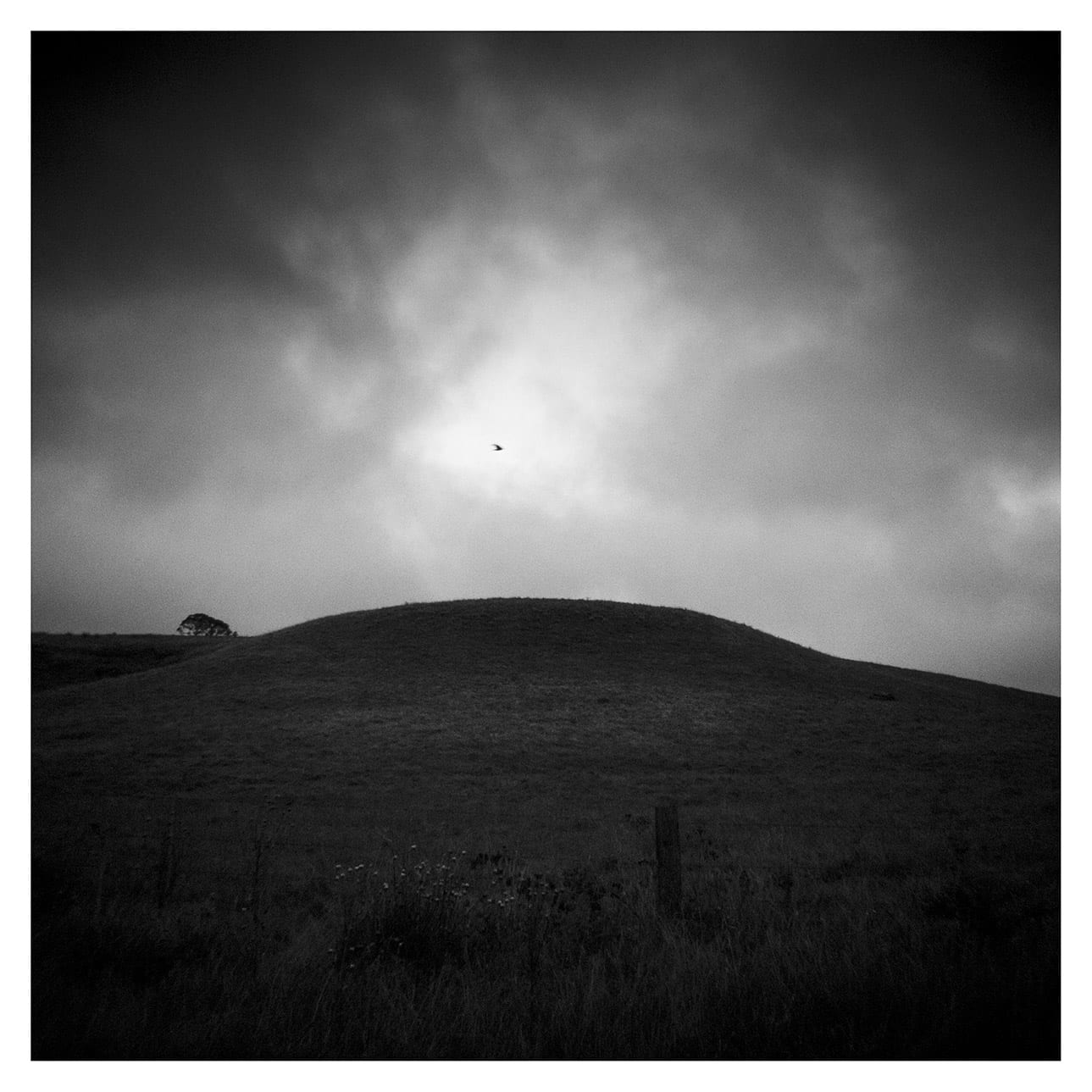

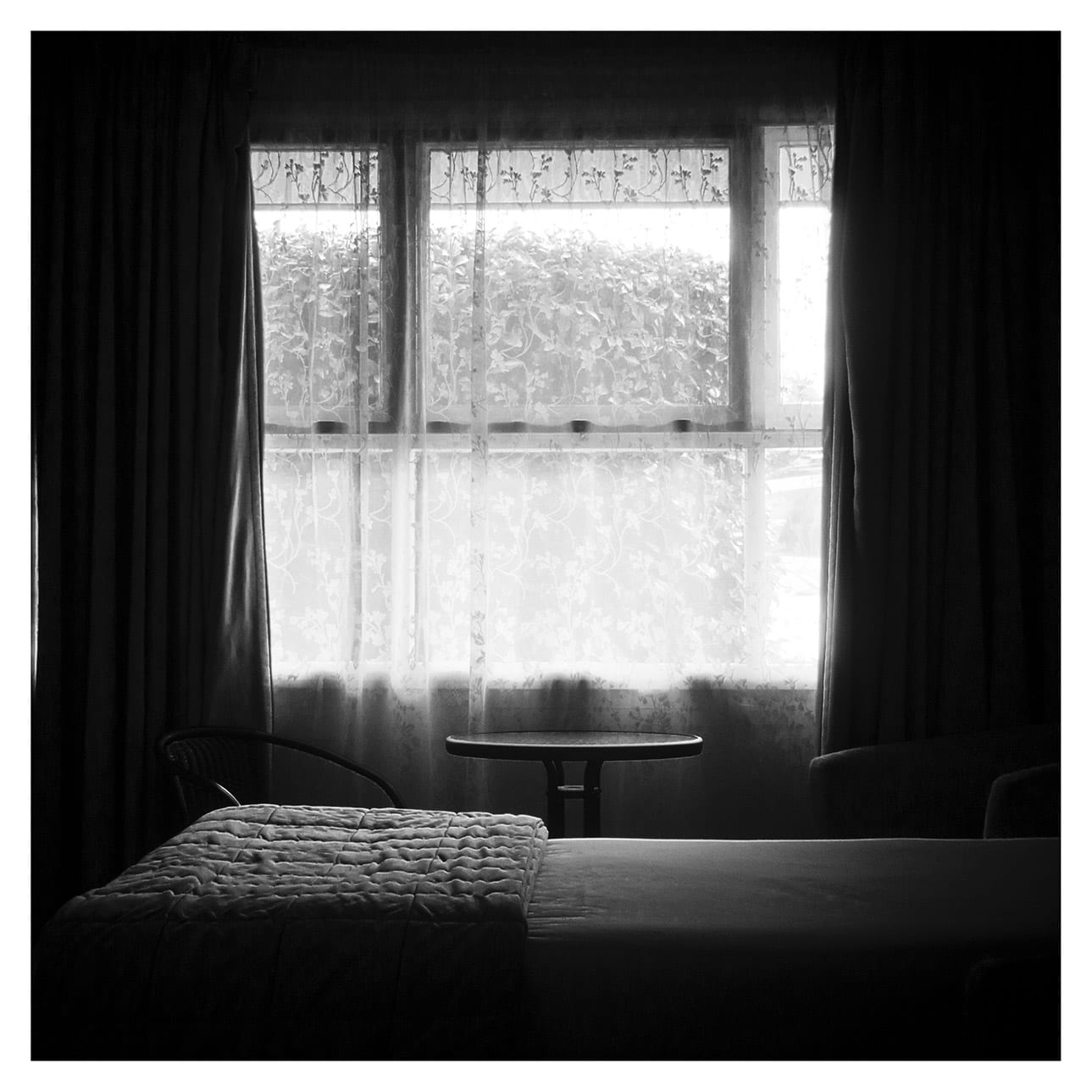

The work is about my personal connection with photography and my experience with creative practice. It connects me spiritually and symbolically with two ancient Japanese philosophies; ikigai and wabi sabi. The simplification of the photographic process with a hyper-awareness of the environment around me is what this body of work attempts to capture. The work displays an ephemeral moment of my life’s journey with images that celebrate the beauty of the everyday with the imperfection of life.

Mitsuhashi (2018) suggests the word ikigai (pronounced iki – guy) is a combination of two Japanese characters iki 生き meaning life and gai 甲斐 meaning value or worth. However, Japanese philosophy is often difficult to translate into western values and language. Mogi (2017) also provides a translated meaning close to Mitsuhashi’s and indicates iki literally means to live and gai reason, while Garcia and Miralles (2017) claims gai translates to worthwhile. The concept of ikigai is for people to find their ikigai by living life while practicing something that gives them a sense of purpose that also derives from personal pleasure. Ones ikigai does not have to be materialistic, success-driven or financial. It is often simplistic values like cooking, growing vegetables, art, fishing and even cleaning.

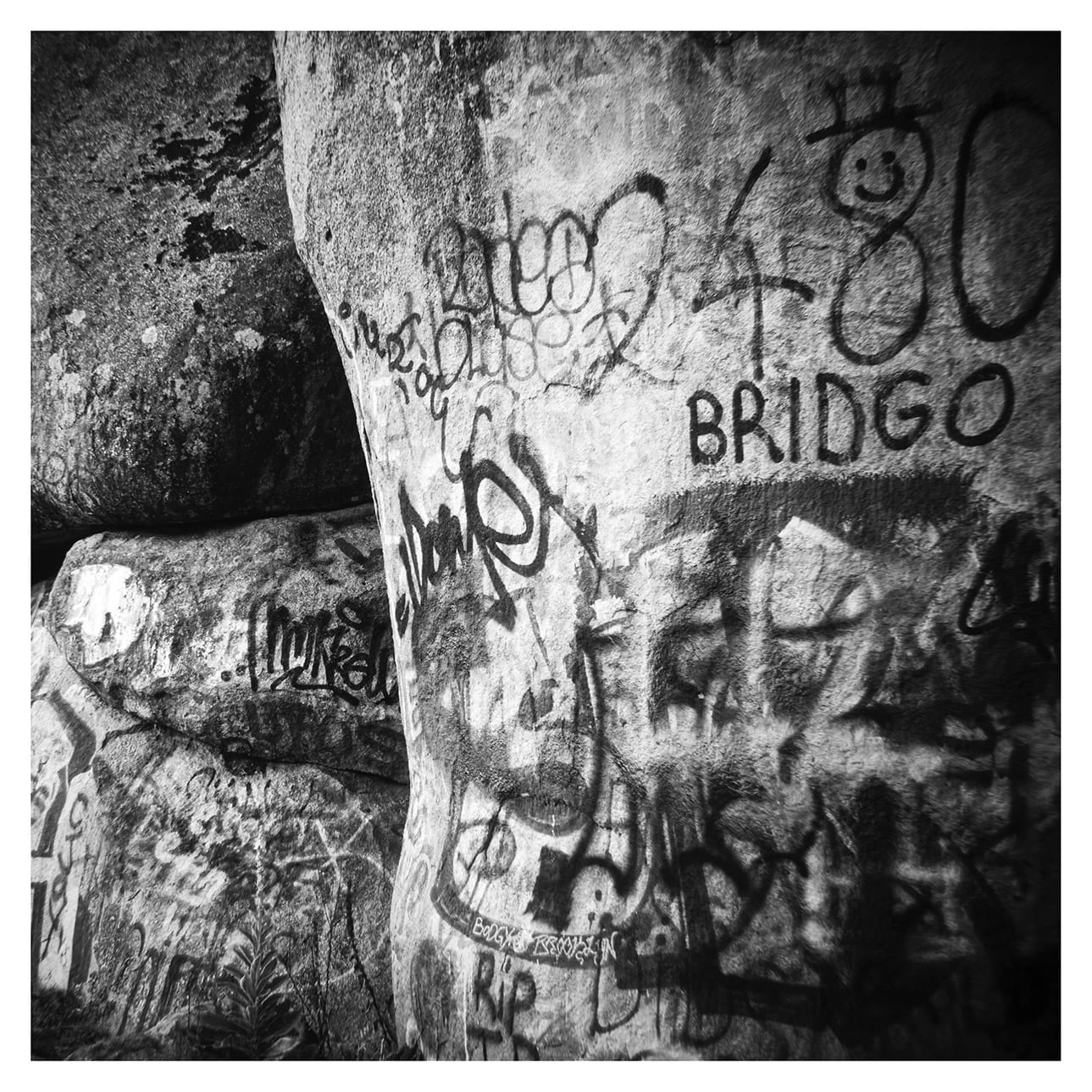

Wabi sabi 侘寂 is another type of Japanese philosophy that examines how we perceive and live life. It is also a combination of two complementary phrases; wabi which is the personal process of finding beauty and sabi which is the joy of things that are imperfect or the decay of things due to the passing of time (Fujimoto 2019). Fujimoto explains how these elements combine to form wabi sabi; “together, these notions form a sensibility that accepts the ephemeral fate of living: celebrating transience and honouring those cracks, cervices and other marks that are left behind by time and tender use” (Fujimoto 2019 p.33). Kempton (2018) describes the wonderment of wabi sabi as feeling the moment “of real appreciation – a perfect moment in an imperfect world” (Kempton 2018 p.5). Wabi sabi can be experienced anywhere and has a lot to do with the awareness of the feeling and environment. Fujimoto (2019) claims “describing an aesthetic consciousness bound up with feelings of both serenity and loss, wabi sabi might be found encapsulated in a simple Japanese garden” Fujimoto 2019, p.33).

This project uses an inexpensive plastic Holga lens attached to a DSLR camera body. The Holga lens attached to a digital camera is a variation of the original medium format film-based Holga cameras, nevertheless, the lens is the same as the plastic film cameras and produces similar artefacts. The project also set down some rules; i) the image must be taken with a Holga lens, ii) the lighting must be available light and iii) the image must be cropped square. The Holga lens is a fixed focal length of 60mm with a fixed aperture. Exposure adjustments can only be made using the shutter speed and/or ISO setting.

Holga cameras were developed in the early 1980’s in Hong Kong as an inexpensive plastic medium format camera for the Chinese market (Malcolm 2017). Holga’s are often referred to as plastic toy cameras with a low-priced plastic meniscus lens. Images display overt artefacts such as film fog or light leaks, low-fidelity images with strong vignetting. The image imperfections, caused by the inexpensive manufacturing and lens design, has produced what is referred to as the ‘Holga aesthetic’ and has become highly celebrated. Bates (2011) notes that other plastic cameras like the Diana also produces a similar aesthetic to Holga cameras.

This body of work is a result of my own ikigai, my passion for creating images that resonate with my personal creative vision. The application of the Holga aesthetic works perfectly for experiencing a sense of wabi sabi with the imperfections clearly witnessed within the images. The loss of fidelity due to the inexpensive plastic lens demands an approach that focuses on form and tone as a compensation for sharpness. The square format is in keeping with the original Holga tradition. The body of work is an eclectic set of urban and natural landscapes that connotes my personal concepts or notions of ikigai and wabi sabi which becomes a highly personalised visual statement. The work intends to provoke a sense of stillness, reduction, tone, form and self-reflection, and to also harmonise with the Japanese aesthetic and its traditions.

The notion of ikigai is an important one within this work, not only as an internalised purpose for life, but more so for the joy this purpose brings to me personally. My ikigai, is largely about the production of a body of creative photography work which brings me great joy. Cartier-Bresson describes this concept of joy when practicing photography in his The Mind’s Eye autobiography. He exclaims “To take photographs is to hold one’s breath when all faculties converge in the face of fleeing reality. It is at that moment that mastering an image becomes a great physical and intellectual joy.” (Cartier-Bresson 1999, p.16). Cartier-Bresson also describes the notion of feeling the image during the hunt for images rather than seeing or taking a more analytical viewpoint when shooting. This is a significant point of difference when considering ikigai as a philosophical notion, which impacts how I feel spiritually rather than how I think. Cartier-Bresson further suggests; “To take photographs means to recognize – simultaneously and within a fraction of a second – both the fact itself and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that give meaning. It is putting one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart on the same axis” (Cartier-Bresson 1999 p.16).

Cartier-Bresson is explaining what it is like to work intuitively and reducing or simplifying the equipment helps promote the notion of working from feeling and gaining the intellectual and personal joy that comes with this approach. I have experienced what Cartier-Bresson is describing throughout this project. It is my connection with photography through my spirit and ikigai. Cartier-Bresson further indicates; “It’s a way of life” (Cartier-Bresson 1999 p.16) and this can be interpreted from a Japanese philosophy perspective as ones ikigai. Nathan Jurgensen (2019) also mentions Cartier-Bresson’s thinking regarding the personal joy photography offers practitioners. He also refers to Jean Baudrillard’s suggestion that there is a certain joy in the transformation of the real into a document within the concept producing a condition of hyperreality (Jurgenson 2019, Baudrillard 1983).

Several theorists like Sontag, Barthes, Jurgenson, Bates have described the condition of photography through how the audience may perceive the work as an extension of reality or reality through the lens of modernity. The intent of this body of work, while it may be interpreted through this lens, is a more egocentric focus on my connection with photography as my ikigai. It does not try to raise issues about the world or society, it is simply a way of expressing how I feel about photography by using photography. The work does however, raise questions about what is photography and what is art? Cotton (2014) examines these questions primarily from an aesthetic theory position but also explains how phenomenology plays a role in how the interaction between the viewer and the photographs operate within different viewing contexts including gallery, newspaper, billposter, family album, screen etc.

Follow GlenN Porter on Instagram

References

- Bates M., (2011) Plastic Cameras: Toying with Creativity, 2nd edition, Focal Press, Oxford.

- Baudrillard J., (1983) Simulations, MIT Press, Cambridge.

- Bunnell P.C., (1994) Introduction, essay found in Michael Kenna: A Twenty Year Retrospective, (2011) Nazraeli Press, Portland.

- Cartier-Bresson A., (1999) The Mind’s Eye: Writings on Photography and Photographers, Aperture, London.

- Cotton C., (2014) The Photograph as Contemporary Art, 3rd Edition, Thames & Hudson, London.

- Fujimoto M., (2019) Ikigai & Other Japanese Words to Live By, Modern Books, London.

- Garcia H., Miralles F., (2017) Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life, Hutchinson, London.

- Jurgenson N., (2019) The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media, Verso, London.

- Kempton B., (2018) Wabi Sabi: Japanese Wisdom for a Perfectly Imperfect Life, Piatkus, London.

- Kenna M., (2017) Holga: Photographs by Michael Kenna, Prestel, London.

- Kenna M., Meyer-Lohr Y., (2015) “Forms of Japan” Prestel, Munich.

- Malcolm F., (2017) Beyond the Visible, essay found in Holga: Photographs by Michael Kenna, p.5-13, Prestel, London.

- Mitsuhashi Y., (2018) Ikigai: Giving Everyday Meaning and Joy, Kyle Books, London.

- Mogi K., (2017) The Little Book of Ikigai: The Essential Japanese Way to Finding Your Purpose in Life, Quercus Editions, London.