Is the Relationship Between Vernacular Photography & Memory Shifting in the Digital Age?

By Lydia Shearsmith (23rd June 2021)

Abstract

This paper investigates the relationship between vernacular photography and memory in the digital age. Specifically, it contemplates how the digital age is affecting vernacular imagery, the relationship we have with memory and finally the representation of the self and its effect on how we are remembered. Throughout I discuss different digital advancements that have developed through the digital age and analyse the effect it has on photography’s relationship to memory.

Informed by the writing of theorists such as Daniel Plamer, David Bate, Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, Geoferry Batchen and Jose Van Dijck, it introduces different viewpoints which help inform the argument. The photographic practice of Corrine Vionnet, Jason Lazarus, Chino Otsuka, Diane Meyer, Greg Sand, Nan Goldin and Chompoo Baritone provide different approaches of how the relationship between photography and memory support such points made through practice / visual illustration.

The themes discussed investigate the morphing nature of vernacular photography; in particular, the impact of the migration from the photograph as physical artefact to a digital file is having on the photograph’s relation to memory. I move on to consider the effects these changes may have on memory itself, focusing on the possibility of there being a death of memory. I conclude with a discussion of how social media is affecting the portrayal of the self and how this affects personal legacy.

Key Words: Vernacular, Family, Memory, Digital, Social Media

Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Chameleon Vernacular

- Chapter 2: The Death of Memory

- Chapter 3: Idealism & the (In)Stability of the Self

- Conclusion

- References

- Bibliography

List of Figures

- Cover Image: Greg Sand (2012) Brothers

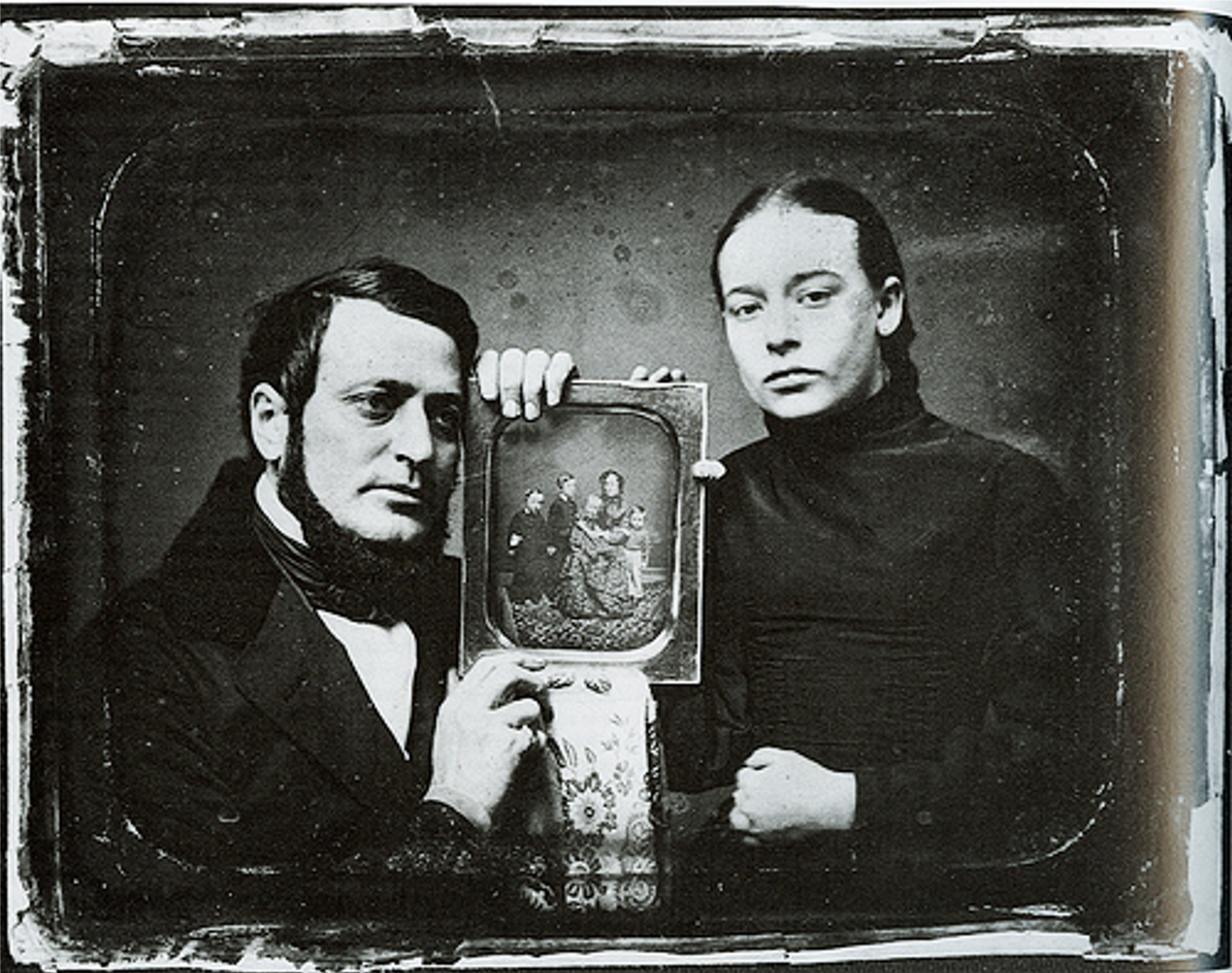

- Figure 1: Unknown (c.1850) Couple with Daguerreotype

- Figure 2: Amalia Ulman (2016) from Excellences & Perfections

- Figure 3: Jason Lazarus (2010) from Too Hard to Keep

- Figure 4: Jason Lazarus (2018) from Too Hard to Keep

- Figure 5: Chompoo Baritone (2015) from #slowlife

- Figure 6: Corinne Vionnet (2005) from Photo Opportunities

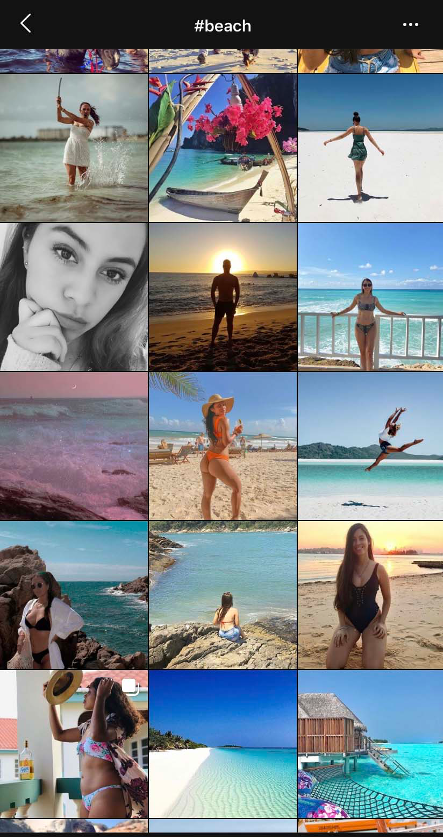

- Figure 7: Screenshot by author (2019) #Beach on Instagram

- Figure 8: Erik Kessels (2011) from 24 Hours in Photos

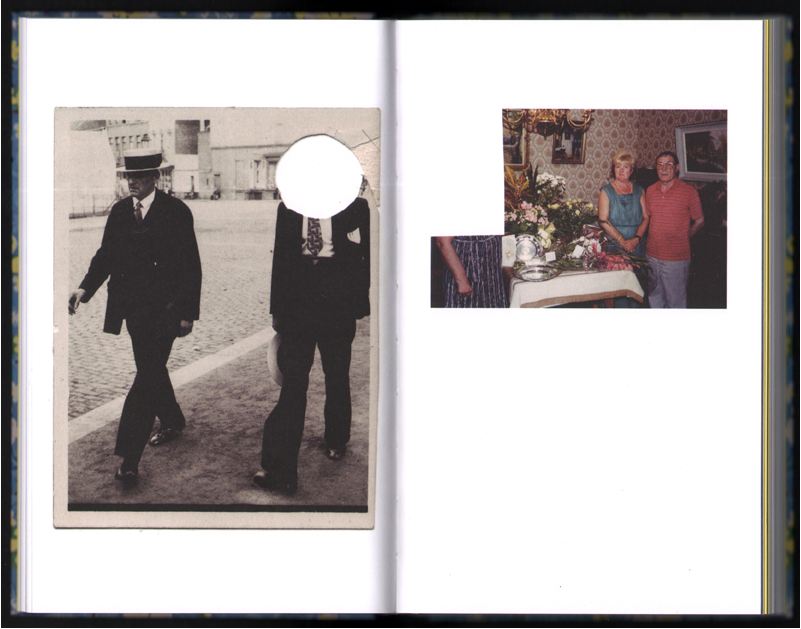

- Figure 9: Erik Kessels (2013) from Album Beauty

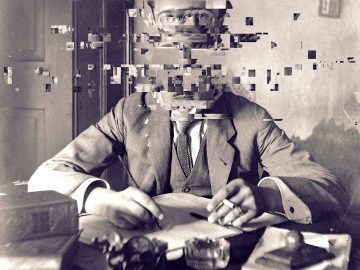

- Figure 10: David Ariel Szauder (2013) from Failed Memories

- Figure 11: Diane Meyer (2013) from Time Spent That Might Otherwise Be Forgotten

- Figure 12: Chino Otsuka (2005) from Imagine Finding Me

- Figure 13: Amalia Ulman (2016) from Excellences & Perfections

- Figure 14: Chompoo Baritone (2015) from #slowlife

- Figure 15: Greg Sand (2011) from Once Removed

- Figure 16: Nan Goldin (1982) Greer and Robert on the Bed, NYC

- Figure 17: Mona Hatoum (1998) from Measures of Distance

Introduction

Since the early 19th century, photographs have played an important role in the act of family life and cultural practices. (Figure 1) These photographs, representations of the visual culture of everyday life, are referred to as vernacular photographs (Batchen, 2014). Vernacular photographs often document special, rarefied moments that the photographer wishes to remember and look back on in the future. The photographs are fragments of reality that anyone can acquire (Sontag, 1977: 4); whether their production is for remembrance, record or for capturing the enjoyment of a moment, vernacular photographs capture everyone’s present with the intent of memorializing it.

However, due to digital and technological advancements, the relationship we have with vernacular imagery is in flux, especially concerning memory; due to the presence of a photograph being a physical object, yet now morphing into a digital file. As a digital file, a photograph has “increased flexibility that may lessen our grip on our images’ future repurposing and reframing, forcing us to acknowledge the way pictorial memory might be changed by ease of distribution” (Van Dijck, 2008: 58). The state of a digital file and the position it can take through the internet and social media has the potential to change the relationship we hold between vernacular imagery and memory. Throughout this paper, I will be exploring this relationship through analysing how vernacular photograph’s form and meaning is changing in a digital climate, assessing how these changes are affecting the ability of memory and finally, how photography is becoming more about self-assurance, than it is about our personal memories. (Figure 2)

Chapter One: The Chameleon Vernacular will assess the progression in the role of vernacular imagery in recent history. Exploring how the change from physical, cherished photographic prints, to digital ways of taking, storing and sharing, is changing the way we view a photograph – Addressing whether we can still place as much importance on a photograph that may never take a physical form. I will be arguing that although vernacular photography holds an essential position in our lives, instead of holding importance in the act of remembrance; they are instead imparting significance on the moment itself and its use as a tool of communication.

Chapter Two: The Death of Memory, explores the role of vernacular photographs in the act of remembrance and how through either personal choice or file corruption, these images could cause a literal loss of memory. I will also reason that photography may not be an accessory for memory, more so a prompt of something that we have forgotten, that we may never remember. Furthermore, I will analyse how the progression of digital technology is creating an opportunity to record and save every aspect of life, resulting in the inability to forget. Applying it to the relationship between memory and forgetting, thus by having memory, how we must have the ability to forget.

Chapter Three: Idealism & the (In)Stability of the Self, will demonstrate how vernacular photography is altering from being a prompt of personal memory to being an idealised representation of the self, specifically an idealised legacy. I will explore how digital visual culture is affecting the way we are representing ourselves, dictating how we want to be seen in the future. I will demonstrate this by looking into the reasons we take and keep photographs of ourselves and the way we present ourselves to the camera. Arguing that through striving for the perfect image, our photographs have started to become a diminished record of who we are.

Chapter 1: The Chameleon Vernacular

Vernacular photographs are often considered to be priceless objects, that “speak to us and for us, reinforcing our memories and histories and cultivating our sense of self, [they become] precious physical traces of our individual identities and histories.” (Zuromskis, 2016: 18). The photograph plays a vital role in documenting who we are, where we come from and can even project an idea of whom we might become. Before the invention of digital photography, there would be a prolonged period between the taking and the viewing of a photograph, which naturally imparts a heightened significance on the photograph. It allows for a reminiscence of the recent past, acting as a reminder that has a physical presence indicating longevity.

Jason Lazarus’ archival project entitled Too Hard to Keep (Figure 3) highlights the profuse connection an individual can have with a physical image. To create the archive Lazarus “solicits submissions of images that are too hard for people to keep but too painful to destroy” (Smith, 2018: 198). The notion that there are photographs that hold that much emotional value to a person they cannot be kept, nonetheless they cannot destroy demonstrates how photographs can be more than just a visual representation of a selected moment. Too Hard to Keep highlights and awareness that once a photograph ceases to exist physically, the connection between its possessor and the moment it depicts is altered, there is a possibility of it being forgotten altogether. However, by handing the photograph into someone else’s possession, in this case, Lazarus’, the moment does not die, it can still hold onto its legacy even if it will never be understood again. The photograph has control over the mortality of a memory. However, how is the change from photographic print to digital file going to affect the emotions attached to a photographic image? (Figure 4)

The development of digital modes of taking, storing and sharing challenges the role of vernacular photography in everyday life. Unlike, the photograph print, a digital file has a disposability due to the ease of its creation. As Susan Murray explains: “The ability to store and erase on memory cards, as well as to see images immediately after taking them, provides a sense of disposability and immediacy to the photographic image that was never there before” (Murray, 2008: 156). The personal value of the photographic image is decreasing due to the accessibility of production and the ability to store an abundance of images without it inhabiting a physical space. Furthermore, due to the instantaneous modes of taking the digital photograph “can speak instantly to the world, and our reminiscence happens in real-time.” (Lavoie, 2018). Taking a photograph is no longer a means of documenting moments to be looked back on as the past but as a moment that is recorded and viewed as the here and the now.

With our reminiscence happening in real-time, the status of a photograph as being a prompt of memory is also changing. The ephemerality of digital files results in the photographic image being regarded as temporary instead of fixed, especially to a younger generation. As Jose Van Dijck state: “Most teenagers consider their pictures to be temporary reminders rather than permanent keepsakes” (Van Dijck, 2008: 62). This indicates that there is an awareness among younger generations of the photograph’s role of being a keepsake of memory, but they choose for it not to be. This could be a result of living in the moment, alternatively, it could be a result of limited life experience. The older we get, the more reminiscent we become. It would be interesting to explore how the perspective of those considered to be ‘most teenagers’ at the time of Dijcks statement has changed with age.

A cause of this attitude towards a vernacular photograph being a brief reminder could be due to the introduction of social media platforms, especially Instagram and Snapchat, which are both predominantly photo sharing networks. These platforms demonstrate a “distinctive swing towards photographs as a currency for social interaction [which] must therefore be interpreted as part of a broader cultural transformation that involves individualisation and intensification of experience” (Palmer, 2010: 168). This indicates how the photographic image becomes a document of the here and the now; becoming a record of experience opposed to one with the intention of remembrance. The broader audience through social media imparts a stronger social significance of a photograph, in contrast to a personal emotional value that a printed photograph may impart. (Figure 5)

Vernacular photographs have taken on an evidential role in everyday life; “Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that the fun was had” (Sontag, 1977: 9). Although, this is still true for physical photographs; the overwhelming number of images on social media platforms and the ease of documenting every moment, indicates that nothing has happened at all if it has not ended up in a photograph. “Photography has become less about the special or rarefied moments of domestic/family living… and more about an immediate, rather fleeting display of one’s discovery of the small and mundane” (Palmer, 2010: 155). Through the ease of uploading images, they no longer hold as great of a significance on any given moment. The photographs have become about proving something has been done, or a place visited opposed to celebrating and recording a special moment with a photograph. This is visualised through Corrine Vionnet’s series Photo Opportunities (Figure 6). To create the images, Vionnet compiles thousands of snapshots found online that relate to a specific tourist destination. The photograph illustrates a mere indication of the number of photographs taken at that specific location and how, through the internet, every one of the files is accessible to the public. This visualises how many people have registered a significance in visiting the location and sharing the fact that they were there.

The abundance of images created as a result of social experience and their aesthetic similarities has a significance in the changing form of vernacular imagery. As visualised through the work of Vionnet, there is a staggering number of photographs all depicting similar if not the same, things and as a result of this, a photograph no longer has to be a person’s own to be used as an instigator of memory. In 1999 Novak stated that: “We experience much of history as photographic moments and these images from our cultural consciousness can trigger our personal memories in ways that our own snapshots often could not” (Novak, 1999). This can be applied to our current circumstance; however, the images do not have to be historical, they can be anyone’s vernacular image that either shares a visual similarity to an experience you have had or depicts a place you have visited. These images still have the potential to spark a memory.

For example, Figure 7 depicts a screenshot of a search on Instagram of images tagged #beach; it is noticeable how visually similar the photographs are. Even if the photograph is not of you in particular that image could still spark a recollection of a photograph you might have taken or a time when you thought about taking a photograph but did not. It also highlights how we have become aware of our own presence within a photograph, often being the subject ourselves, instead of the one photographing. We have become the subject of our personal photographs as opposed to the people that surround us. This has the potential to alter how the photograph acts in conjunction with memory, which I will further discuss in Chapter Three.

The visual similarity and urge to document everything on social media platforms is leading to an image culture which “deals with ephemeral lifestyle concepts which are frequently changed and updated in the online catalogues through which they are accessed” (Wells & Henning, 2015: 341). Due to the mass of images, it is harder to keep track of what has been taken and shared. (Figure 8) There is an ability to go back and view the photographs at any given point due to their accessibility; however, it is more common to go on social media and scroll through other people’s most recent photographs, placing us in a position where the present is persistently being viewed. This results in greater importance being placed on the consumption of other people’s photographs opposed to our own, and the social interactions they may create. Photographs are posted to make other people aware of where we have been and what we have done, creating the possibility of a future conversation regarding the event. This signifies that an act of remembrance may be a result of a conversation regarding a shared image as opposed to the image itself.

Through the digital age, vernacular photography is a chameleon; it is morphing and changing to fit into different circumstances to be as accessible to anyone that chooses to take photographs. The photographic print can still be seen to have an important position in most homes. Nonetheless, its visual language has morphed into different forms to allow for different styles of imagery for different forms of sharing. Whether it be an Instagram post, to depict a good time or a quick photo to a friend as a form of communication. However, I agree with the statement from Nathan Jurgenson that: “Photography has gone from being a medium for the collection of important memories to an interface of visual communication”. (Jurgenson, 2019: 13-14) The most considerable change for vernacular photography is that its significance no longer lies on memory and recollection but communication, as the visual prompts for memory can come from elsewhere.

Chapter 2: The Death of Memory

In Chapter One I outlined how the instantaneous process of taking and viewing an image places us in the here and now, resulting in a system where “Our contemporary documentary vision positions the present as a potential future past, creating a nostalgia for the here and now” (Jurgenson, 2019: 7). The photographs we take make us particularly aware of our stance in the present, resulting in the images we take being ones of self-representation opposed to records of memories to be looked back on in the future. Digital technology allows for our personal archive to be easily accessible, resulting in us revisiting our recent past more frequently than our distant past. This is especially relevant to individuals that lived in a time before digital photography, as to revisit the childhood pictures, they would have to find the physical images. This results in importance been placed on our recent histories, placing a heightened significance on living in the moment opposed to reminiscing our distant past. “The images produced by camera phones are typically experienced as ephemeral artefacts, unlike analogue photographs that are usually meant to be kept” (Palmer, 2010:158), images taken now are short-lasting, revisited close to the time of being taken and quickly forgotten about due to a new wave of imagery.

The personal decision to dispose of images, as a means of controlling the abundance of photographs, also adds to the ephemeral nature of vernacular imagery today. Wells (2015) argues that: “The delete button may be changing the relationship of photography to biography as images that might have been valued in retrospect are now rapidly consigned to oblivion before history and nostalgia can do their work” (Wells & Henning, 2015: 337). However, I believe that we place a significance on the photograph at the moment it is taken, experiencing nostalgia in the present, which results in our value of the photograph quickly depleting as new photographs take their places. This results in us happily deleting and disregarding photographs before they become a relic of our past. Sontag states that: “Time eventually positions most photographs, even the most amateurish, at the level of art” (Sontag, 1977: 21). This indicates how a photograph can have an unpredictable significance over time, nonetheless due to the ephemerality and readiness to dispose of images to replace them with new ones; there is a potential for these significant photographs to be deleted and forgotten about, obstructing our potential for recollection, and quite different from the physical artefact of the family album. (Figure 9)

There is the possibility for the death of memory through a personal choice to delete photographs, but what happens when the loss comes from an error beyond our control, one of file corruption. Technological advancements are hard to keep track of and “as we move from one computer operating system or storage medium upgrade to another unprecedented amounts of information are being lost or trapped in obsolete formats” (Wells & Henning, 2015: 344). There is a fragility that comes with digital files and if they are not looked after they run the risk of deleting moments in our lives that we have entrusted to photographs that have fallen into an abyss that they cannot be returned from.

This fragility is illustrated through the work of David Ariel Szauder whose project Failed Memories (Figure 10) creates a visualisation of the process of recalling an image that has at some point being lost. The digital visual language used by Szauder through the image creates a dialogue between naturally forgetting and digitally forgetting and how either way, the loss of an image can cause a sense of corruption in its recollection.

In my opinion, Diane Meyer more successfully addresses this concept through her series Time Spent That Might Otherwise Be Forgotten (Figure 11) by borrowing “the visual language of digital photography through an analogue process which creates a relationship between forgetting and digital file corruption” (Meyer,2017). Unlike Szauder, Meyer uses personal imagery which creates a more emotional reaction to viewing the photographs. The barriers Meyer creates through stitching into the photographs means that there is anonymity of the subject; however, the scenes can still be deciphered, and the viewer can often pinpoint a similar image from their history, such as sitting in front of the Christmas tree, making every photograph personal. Meyer’s work highlights how although the digital file is more fragile and ever-changing if a physical image is damaged or lost, it is just as fragile. The loss of memory through the loss of an image is just as relevant to old ways of storing as it is to new. The loss of memory is not a new thing; it has just become more noticeable through a higher abundance of images in the digital age.

There is a potential for digital storage to allow for the creation of a perfect memory, which could instigate the death of memory. Digital storage “is so omnipresent, costless and seemingly ‘valuable’ – due to accessibility, durability and comprehensives – that we are tempted to employ it constantly” (Mayer-Schönberger, 2011: 126). The ease of using and accessing digital storage methods creates the potential to record every aspect of life, giving us the ability to digitally ‘remember’ any given moment. This then prevents the ability to forget, and when “The art of memory relies on the art of forgetting” (Rumsey, 2016: 12), it introduces a paradox between the relationship between photography and memory. Photographs remind us of specific moments in time; however, it is rarely that exact moment that the photograph causes us to recollect.

Roland Barthes articulates that a photograph is “never, in essence, a memory, but it actually blocks memory, quickly becoming a counter memory” (Barthes, 1994: 91). We have become reliant on the photograph acting as a memory. When in reality a photograph is a visualisation of what a moment looked like opposed to a snippet of the actual event. We entrust a photograph to possess a memory that only we can recall, focusing so much on capturing a moment that we do not actually take it in enough to become a memory.

The concept that a photograph becomes a barricade for memory can be illustrated through Chino Otsuka’s series Imagine Finding Me (Figure 12). The work consists of Otsuka digitally inserting herself back into her childhood photographs, creating a dialogue surrounding identity and personal history. Discussing her work Otsuka states: “I’m embarking on the journey to where I once belonged and at the same time becoming a tourist in my own history’ (Otsuka in Azarello, 2015). The idea of being a ‘tourist’ creates a sense of the unknown. Otsuka is exploring her own history; nonetheless, she is in unknown territory. Even though she has the photographic evidence of her history of being in that moment, she has no recollection of it. Otsuka is navigating the map of her own life through photographs, but there is only so much she can learn. An imaginary conversation could be had between her two selves, but only she can answer the questions of her own history, but the photographs cannot help insight a recollection.

There is a noticeable risk in both digital files and physical print for a photograph to be easily lost. However, I believe it is the overconsumption of images and the ability to store endless amounts of images that run a risk of corrupting the relationship we hold between photography and memory. From an extreme perspective: “We may enter a time in which – as a reaction to too much remembering, with too strict and unforgiving link to our past – some may opt for the extreme and ignore the past altogether for the present, deciding to live in the moment” (Mayer-Schönberger, 2011:126). The endless amounts of photographs we keep can result in reminders of our past appearing that we might not want to be reminded of. This has the potential to put us in a cynical position where we no longer want to remember past at all, living entirely in the present. Even if the photographs do not recall painful memories of our past the endless stream of photographs paired with our nostalgia for the present is leading to a similar effect even if it is not a conscious decision.

Chapter 3: Idealism & the (In)Stability of the Self

Due to advancements of social sharing platforms (such as Instagram), our photographs are now shared to a large audience in real-time, opposed to them being kept and shared between a smaller selection of close relatives and friends. This creates a keen awareness of how we are presented and perceived by others in a virtual space. The photographs we take and share become “a certificate of presence” (Barthes, 1994: 87). The photograph can place us in a particular position in time and space, documenting the path we are travelling and making others viewing the photographs aware of it as we go. The vernacular photograph is just as much a record of our personal ‘story’ as it is an accessory for remembrance. However, this record comes an awareness of what we choose to portray and how we choose to portray it. The photograph is a “self-representation that is less about seeing things as they are than about seeing things as we want or imagine them to be” (Zuromskis, 2016: 20), thus resulting in us mediating every aspect of how we are depicted to our ‘audience’.

Taking a photograph requires the subject to perform for the camera and the photographer, however, with the increased popularity of the ‘selfie’ we have become both the subject and the photographer, controlling every aspect of how we are to be displayed to an audience. (Figure 13) Through the process of taking a photograph, we are presenting ourselves not as whom we think we are, and not as whom the viewer thinks we are but as a representation of whom we think the viewer thinks we are (Jurgenson, 2019: 57). We create a version of ourselves that we believe our friend and followers want to see.

Although this is visible through the way we present ourselves in a self-image, it is possibly even more prominent in the way we picture our surroundings and home lives. This is illustrated through Chompoo Baritones series #slowlife (Figure 14). Through the series, Baritone depicts the idealised scene we choose to show other people on our Instagram feed, in contrast to the ‘real’ picture, which shows an accurate depiction of how we live. This series highlights how hyperaware we are of our self-image, showing how we curator an idealised version of ourselves for the public while hiding our real selves, just outside of the frame.

However, due to this mindset and the idealised images that are produced because of it, most vernacular images are beginning to look the same, depicting a perfect reality. These staged mediation of ourselves may be aesthetically pleasing, but they lack soul and emotion. As Roland Barthes would put it, these photographs have a studium, they spark and enthusiasm without special acuity (Barthes, 1994: 26) but they do not contain a punctum, the “accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me” (Barthes, 1994: 27). The photographs have visual interest, but they do not have any emotional power over the viewer or even the subject of the image.

The work of Greg Sand (Figure 15) demonstrates how powerful a punctum can be. Sand’s series Once Removed, takes the subject away from an old photograph, leaving only the studio and a chair within the frame. However, when viewing the photograph, there is an apparent loss of presence, a realisation that there should be a person there. “The removal of the subject who is very much alive in the photograph – forces the photograph to more truthfully depict a present reality in which the subject no longer lives” (Sand, 2011). Sands photographs make us aware that “photographs remind us that memorialization has little to do with recalling the past; it is always about looking ahead toward that terrible, imagined, vacant future in which we ourselves will have been forgotten” (Batchen, 2004:98).

Sand’s photographs successfully evoke this by heightening the effect of the punctum through erasing the details of the stadium. What interests the viewer is the lack of a subject, but what ‘pricks them’ is the nostalgia created through the sense of loss. However, the viewer has no idea what or who they are nostalgic for, just an awareness that they are not in a position to be able to remember the person. In contrast to the vernacular photographs, we are creating which produce a legacy of idealism as opposed to an accurate depiction of who we are. We have lost our punctum through digital visual culture.

Our vernacular photographs are more than just a prompt for recollection, but they help to record our personal legacy. However, due to the aesthetic sameness and lack of emotion they possess, our photographs run the risk of writing a bland history, which depicts what we looked like and the perfect things we did in our lives, but not giving an insight as to who we actually where. We create a record of ourselves “to present a sense of being a coherent person over time, to strengthen social bonds by sharing personal memories, and to use past experiences to construct models to understand inner worlds of self and others” (Van Dijck, 2007:3). The documents of ourselves make our legacy genuine, they show the good and the bad and how we became the person we did, but now due to the idealised image promoted through social media everyone’s legacy is a depiction of what they want to show as their perfect selves opposed to their real selves.

The photographs that depict a more authentic version of who we are those which present ourselves naturally not in a controlled environment and staging but the ones that catch us off guard and have a spontaneity. This can be demonstrated through the snapshot aesthetic used by Nan Goldin (Figure 16). Goldin describes the process of what she wants to capture within her work as an exact picture of her world “without glamorisation, without glorification. This is not a bleak world but one in which there is an awareness of pain, a quality of introspection’ (Goldin, 1996:6). Goldin strives to capture an informed depiction of what the real world is like. Although the images can sometimes be uncomfortable and troubling, not depicting an idealised view, they depict the truth. Furthermore, create a sense of truth as to who the people captured actual are and how they live. Remembering the difficult times can often make the good even better. However, if we continually present ourselves in an idealised form, our legacy will not be exciting because the perfect will start to seem ‘normal’.

Due to the idealised image, there is much pressure being put on individuals to have an idealised life. It is often hard to decipher between whether a photograph depicts the truth of a person or a façade of whom they want to be. This creates a position in which “There is a pressure for photography to structure everyday life in the very process of representing it” (Lister, 1995: 130). Instead of becoming a record of what is happening in a person’s life, the photograph becomes the aim of a person’s life. Photographs can start to influence the places we want to be, the food we want to eat and the person we want to become. “Everything exists to end in a photograph” (Sontag, 1977: 24) instead of the photograph being a result of being in a moment that we feel is special enough to want to remember so we photograph it.

Vernacular photography has become about creating a perfect legacy, due to our awareness that photographs are how we will be remembered, paired with a social pressure to present an idealised version of ourselves to others. However, we seem to have lost sight that our history and legacy develops from a cultural and personal outlook on the photograph. Photography is not about the technology used or the aesthetic it follows, but it depends on our cultural and subconscious way of seeing and reading. Photographs as record give us a position, identity and a power through security. (Wells & Henning, 2015: 323) Security of a legacy, however, if we conform to visual cultures, this security may become challenged, resulting in our legacy being lost or untruthful.

Conclusion

The relationship between photography and memory is definitely being affected by the digital age. I have found that “memory and photography change in conjunction with each other, adapting to contemporary expectations and prevailing norms” (Van Dijck, 2008: 70-71). The role of the vernacular image is morphing and changing into multiple different forms; they exist in the physical form and in multiple different digital formats. However, their form is majorly shifting into one of communication and ephemerality, placing heightened importance on the here and the now.

In terms of the vernacular photograph leading to the death of memory, it places us in a position where memory is being affected by multiple different variations of memory loss which often become contradictory. However, the most concerning form of loss comes from our ability of over documentation our lives through the accessibility of digital technology. Moreover, because “remembering also institutes a kind of forgetting” (Bate, 2010), the ability never to forget profoundly effects our ability to remember.

The idealised self-image is where the relationship between memory and photography becomes is challenged the most. As Barthes states “The photograph does not call up the past. The effect it produces upon me is not to restore what has been abolished (by time, by distance) but to attest that what I see has indeed existed” (Barthes, 1994: 82). However, due to the effect of social media and a strife for perfection, we are creating a document of our existence that only depict what we look like. Depicting an idealised perspective of the relationships we have and the places we have been. The search for recording ourselves to create a legacy means that we place less importance on those around us and the spontaneity. It is no longer about our personal act of remembrance but of how we are to be remembered.

Throughout the process of writing this paper I have come to realise how ever changing the forms of vernacular photography are and how their connection to memory can differ to every person. I had not thought to consider the age group of people and how this may affect their response to photography; but, also how as we age, our relationship with memory changes. This could result in a completely different relationship between, people, memory and photography and the digital age is another factor to be considered. I found through writing this paper that visual trends have a powerful significance on the way we view any images and that our place in culture can affect the way we view photographs as we do.

If I were to continue with this research, I would like to consider how different media, beyond photography, plays a significance in our relationship to memory, especially home video. I feel that this would create an exciting dynamic between the way we choose to depict ourselves in images to the way we act in the everyday. I would also like to explore how different cultures may have a different relationship to vernacular photography, specifically those that are not westernised. (Figure 17) I would also pay closer attention to the complexity of memory, doing more research into the psychology of memory to be able to apply my findings into broader contexts.

References

- BARTHES, ROLAND. (1994). Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. London: Vintage.

- BATCHEN, GEOFFREY. (2004). Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- BATCHEN, GEOFFREY (2014). ‘Vernacular Photography’. Oxford Art Online. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T2254188. [Accessed 16 November 2019]

- BATE, DAVID. (2010). ‘The Memory of Photography’. photographies 3(2), [online]. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17540763.2010.499609. [Accessed April 2019]

- GOLDIN, NAN, HEIFERMAN, MARVIN., HOLBORN, MARK. and FLETCHER, SUZANNE. (1996). The Ballad of Sexual Dependency New York, N.Y: Aperture.

- HOSTETLER, LISA and GREEN, WILLIAM T. (2016). A Matter of Memory: Photography as Object in the Digital Age Rochester, New York: George Eastman Museum.

- JURGENSON, NATHAN. (2019) The social Photo – On photography and social media. London: Verso.

- LAVOIE, STEPHANE. (2018) Modern Photography is changing how we remember our lives. OneZero [Online]. Available at: https://onezero.medium.com/modern-photography-is-changing-how-we-remember-our-lives-4b59adab4a2e [Accessed 04 November 2019

- LISTER, MARTIN. (1995). The Photographic Image in Digital Culture. Routledge: Oxon.

- MAYER-SCHÖNBERGER, VIKTOR. (2011). Delete: the Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- MEYER, DIANE. (2017) ‘Time Spent That Might Otherwise Be Forgotten 2011-2017’. Diane Meyer [Online] Available at: http://www.dianemeyer.net/projects/Time_Spent/timespent.html [Accessed: 09 April 2019]

- MURRAY, SUSAN. (2008). ‘Digital Images, Photo-Sharing, and Our Shifting Notions of Everyday Aesthetics’. Journal of Visual Culture 7(2), 147–63.

- NOVAK, LORRIE. (1999) ‘Collected Visions’ in Hirsch, M. ‘The familial gaze’, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH

- OTSUKA, CHINO. in AZZARELLO, NANCY. (2014) ‘chino otsuka inserts her adult self into photos from her youth’. Designboom Jan 2014 [online]. Available at: https://www.designboom.com/art/chino-otsuka-inserts-her-adult-self-into-photos-from-her-youth-01-13-2014/ [accessed 10 November 2019]

- PALMER, DANIEL. (2010). ‘Emotional Archives: Online Photo Sharing and the Cultivation of the Self’. photographies 3(2), [online], 155–71. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17540763.2010.499623. [Accessed 30 October]

- RUMSEY, ABBEY SMITH. (2016) when we are no more. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

- SAND, GREG. (2011) Once Removed. Available at: https://gregsand.net/copy-of-remnants-1 [Accessed 10 November 2019]

- SMITH, SHAWN MICHELLE. (2018). ‘Archive of the Ordinary: Jason Lazarus, Too Hard to Keep’. Journal of Visual Culture 17(2), 198–206.

- SONTAG, SUSAN. (1977) On Photography. London: Penguin.

- VAN DIJCK, JOSÉ. (2007). Mediated Memories in the Digital Age Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

- VAN DIJCK, JOSÉ. (2008). ‘Digital Photography: Communication, Identity, Memory’. Visual Communication 7(1), 57–76.

- WELLS, LIZ and HENNING, MICHELLE. (2015). Photography: A Critical Introduction. Fifth edition. London, [England]; Routledge.

- ZUROMSKIS, CATHERINE. (2016) ‘Snapshot Photography, Now and Then: Making, Sharing, and Liking Photographs at the Digital Frontier’. Afterimage 44(1-2), [online], 18–22. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1806222744/.

Bibliography

- BATCHEN, GEOFFREY. (2013) Observing by Watching: Joachim Schmid and the Art of Exchange. Aperture #210 online Availale at: https://aperture.org/blog/observing-by-watching-joachim-schmid-and-the-art-of-exchange/ [Accessed 6 November 2019]

- BATE, DAVID. (2010) ‘The Memory of Photography’. photographies 3(2), [online]. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17540763.2010.499609.

- BRIDLES, JAMES [presenter]. (2019) ‘Machine Visions’. New Ways of Seeing. BBC Radio Four [online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000458l [Accessed May 2019]

- DERRIDA, JACQUES and PRENOWITZ, ERIC. (1998). Archive Fever: a Freudian Impression Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press.

- MANOVICH, LEV. (1995) The paradoxes of digital photography. in AMELUNXEN, HUBERTUS VON, IGLHAUT, STEFAN. and ROTZER, FLORIAN. Photography after Photography: Memory and Representation in the Digital Age Gordon & Breach Arts International.

- STALLABRASS, JULIAN. (1996). GARGANTUA: MANUFACTURED MASS CULTURE. LONDON: VERSO.

- STYERL, HITO. (2009) ‘In Defence of the Poor Image’. E-flux #10. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/ [Accessed 30 October 2019]

- SZAUDER, DAVID ARIEL. (N.A) Failed Memories. Available at: http://www.davidarielszauder.com/#/failed/ [Accessed 14 November 2019]

- VIONNET, CORINNE. (C. 2005) Photo Opportunities. Available at: http://www.corinnevionnet.com/photoopportunities.html [Accessed 10 November 2019]

Follow Lydia Shearsmith on Instagram