by Louis Stopforth (9th december 2019)

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes proposes that ‘the Photograph is flat’ (Barthes. 1993. p.106). However photographic materiality has come into question by artists, curators, and critics alike after much deliberation in regards to the medium, procuring that the photograph no longer was to be read as ‘flat’ but that it had a tangibility to it that could be felt and experienced. This exploration of the medium refuted that a photograph was merely an invisible vessel for information, but rather it could be an object of interest in its own right as well as having its materiality contribute to its place as a descriptor.

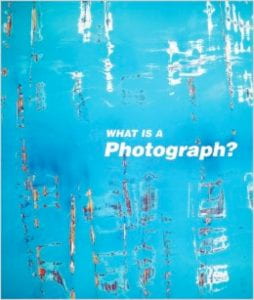

The Photography into Sculpture held at MoMA in 1970 (Fig.1) was a seminal exhibition in allowing artists and photographers alike to begin the exploration of photographic materiality as the focal point of their work, superseading depiction. Peter Bunnell, the curator of this exhibition, one year previously wrote a short essay ‘in which he identified a body of work ‘calling attention to the photographic artifact’ (Batchen. 2002. p.110).

The importance of this exhibition was how ‘the primacy of the image was traded for the primacy of the object, where each work was not ‘’a picture of, but an object about something”’ (Statzer. 2014).

Since then numerous artists, works, exhibitions and essays have focused on the physicality of the photograph, and to more experimental and conceptually charged extents. Two artists I explore here are Marlo Pascual and Wolfgang Tillmans, who have both produced works discussing the materiality of photography but in quite dissimilar ways.

Marlo Pascual (b.1972) and her distorted, ruptured, torn, and intervened with photographs (Fig. 2) instantly defies unawareness to the photographs material presence; ‘the photographs two dimensionality is revealed as a fiction’ (Batchen. 2002. P.110). The recognition of photographic materiality is one that does not effortlessly come to our attention, like other art forms, hence Pascual’s contentious alteration of the photograph.

She states ‘I want it to be physically imposing’ (Pascual, 2012). Pascual’s work discusses materiality in the most extreme of ways, aggressively intervening with the photographic object.

Wolfgang Tillmans (Fig. 3) on the other hand is an example of how photographic work can deal with materiality in both a physical way as well as a photographically representational way (a photograph in its ‘institutionalized’ sense). In contrast to Marlo Pascual, Tillmans work in regards to materiality speaks more intrinsically to photography itself as it does not use exterior materials to itself. For this to be appreciated one must observe two projects simultaneously: Lighter and paper drop.

Tilllmans’ exhibiting of Lighter (2005 to present) consists of an ongoing series of prints that have been folded and bent, protruding into space (Fig. 4). They speak universally of both photographic process and photographic materiality due to there being no personal vision in the trace ‘image’ of the work. If there were clearly recognizable depictions on the surface of the image it would become misconstrued and associated with something rather than the photographic self. Instead the abstract coloring we are presented with is a comment on the process of making a photograph (the colours being the effects of variations in the conditions of light in the darkroom on the photographic paper). Whereas the folding and bending of the paper talks about all photographs material nature. ‘Lighter invite(s) us to think of photography not in terms of an image, but structurally’ (Eichler. 2015. P.11).

Alongside his more dimensional pieces, however, Tillmans uses photography in its more traditional sense of depictional representation (Fig. 5) as a way of personally investigating the broader notion of all things being dimensional.

With his paper drop (Fig. 6) prints he uses photography typically how it is expected; creating a visible and recognisable trace of a moment. Despite this, these prints discuss materiality much the same as the Lighter works as when they are displayed alongside each other, and when we view the flat surfaced paper drop photographs the same as we would any other photograph, we observe that what is depicted is a physical photograph ‘folded back on itself forming a reclining tear-drop shape’ (Eichler. 2015. p.11).

The result of this is that Tillmans produces a ‘study of photography looking at itself’ (Eichler. 2015. p.11); displaying its physicality without manifesting itself into something with more form than itself.

Therefore it is possible to be attentive to both reference and representation whilst the concept of the work is still dedicated to the physicality of the photographic self.

References

- Barthes, Roland. (1993) Camera Lucida. Published by ‘Vintage Classics’ in 1993. Originally published in French in 1980.

- Batchen, Geoffrey (2002) Each Wild Idea. Published by ‘MIT Press’, London, in 2002. Paperback First Edition.

- Eichler, Dominic (2015) Wolfgang Tillmans: Abstract Pictures. Published by ‘Hatje Cantz’, Ostfildern, Germany, in 2015.

- Pascual, Marlo (2012) Marlo Pascual: Selected Works by Marlo Pascual. Saatchi Gallery [WWW]

- Statzer, Mary (2014) Mary Statzer on ‘Photography into Sculpture’, New York, 1970. Aperture [WWW]