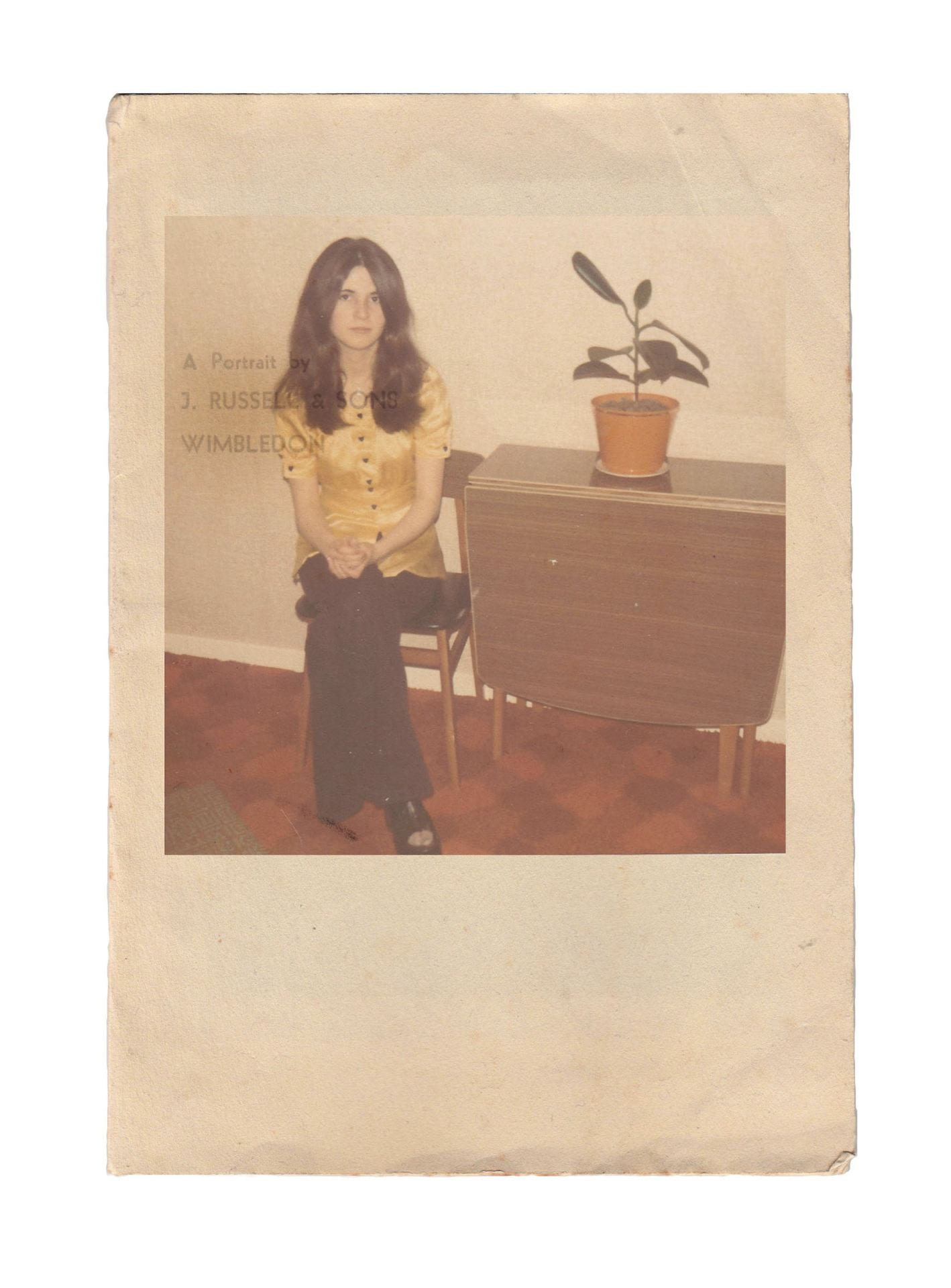

Sofia Conti

Sofia Conti’s practice focuses mainly on social documentary work, She is based in Glasgow, Scotland. Over the past four years she has embarked upon her photography journey as a mature student. She achieved a Distinction in a BA Photography degree at Robert Gordon University, Gray’s School of Art and is currently studying MA Photography at Falmouth University. The intentions of the projects produced are to raise social awareness surrounding issues that aesthetically enlighten the audience to evoke a change in attitudes surrounding the subject matter. Sofia has achieved several esteemed photography awards in the UK and abroad, most recently with the Portrait of Britain. Her work has been exhibited at the Royal Academy 195th Annual Exhibition, The Scottish National Portrait Gallery and Landings 2021.

View The Glasgow Effect on Issuu here

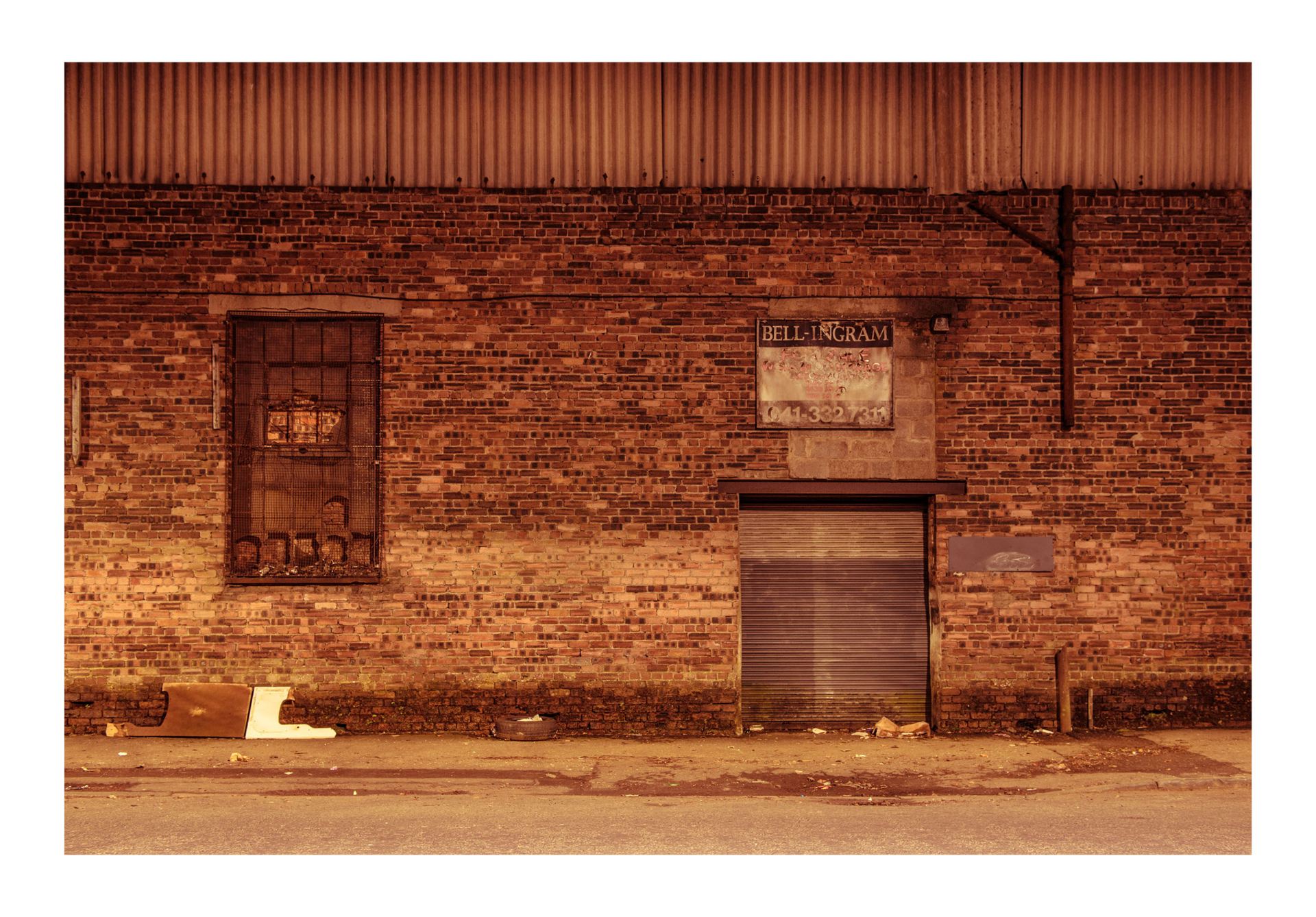

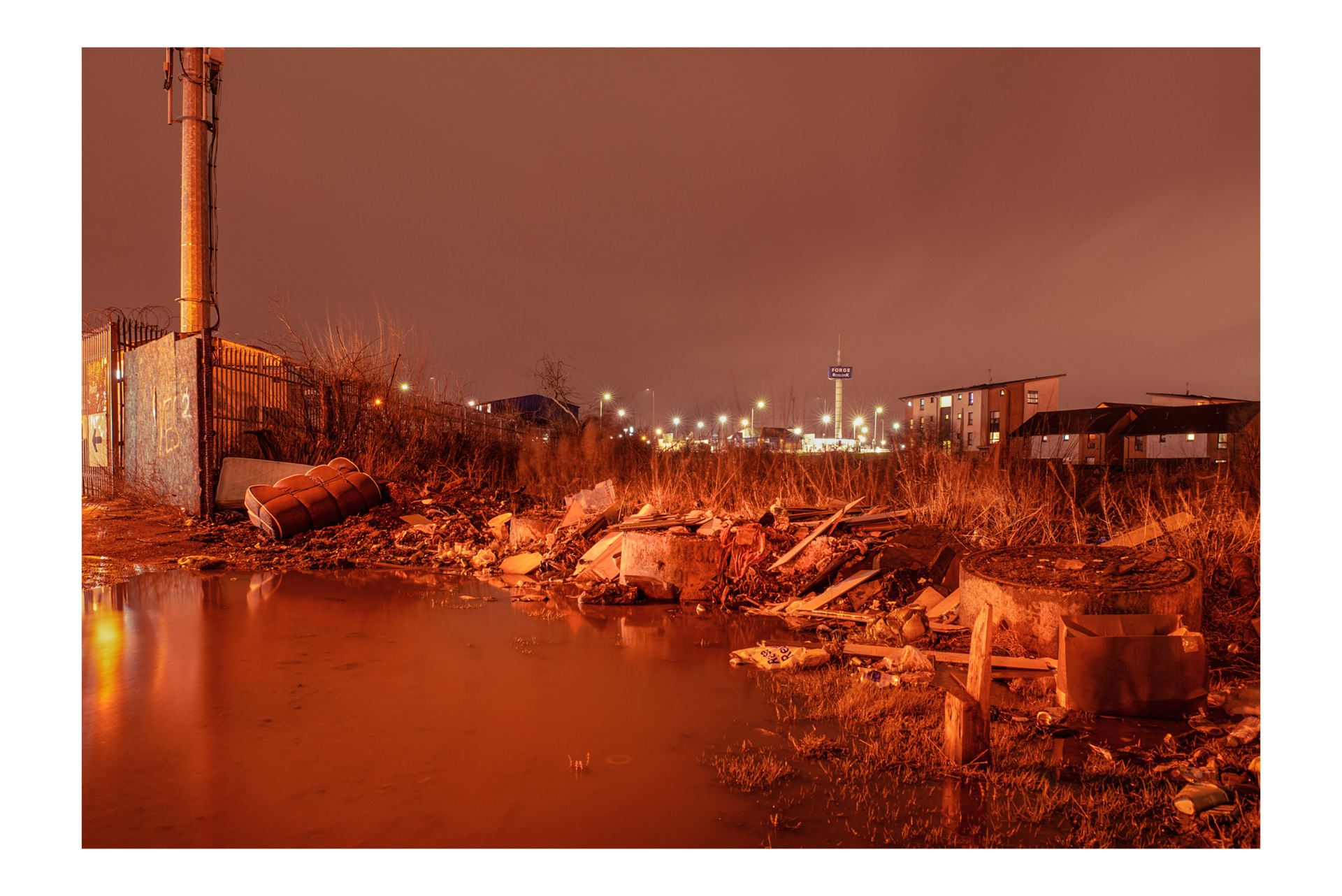

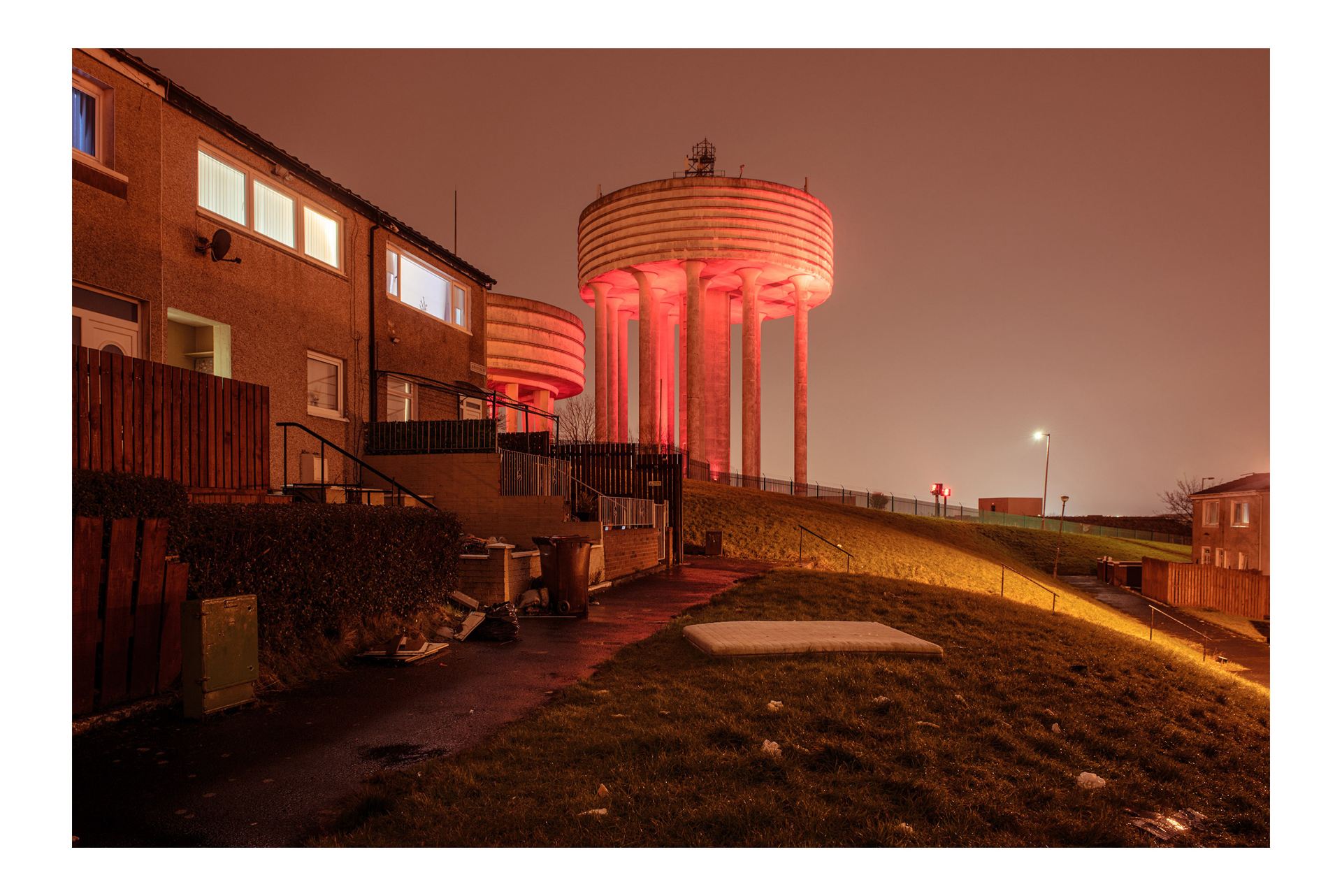

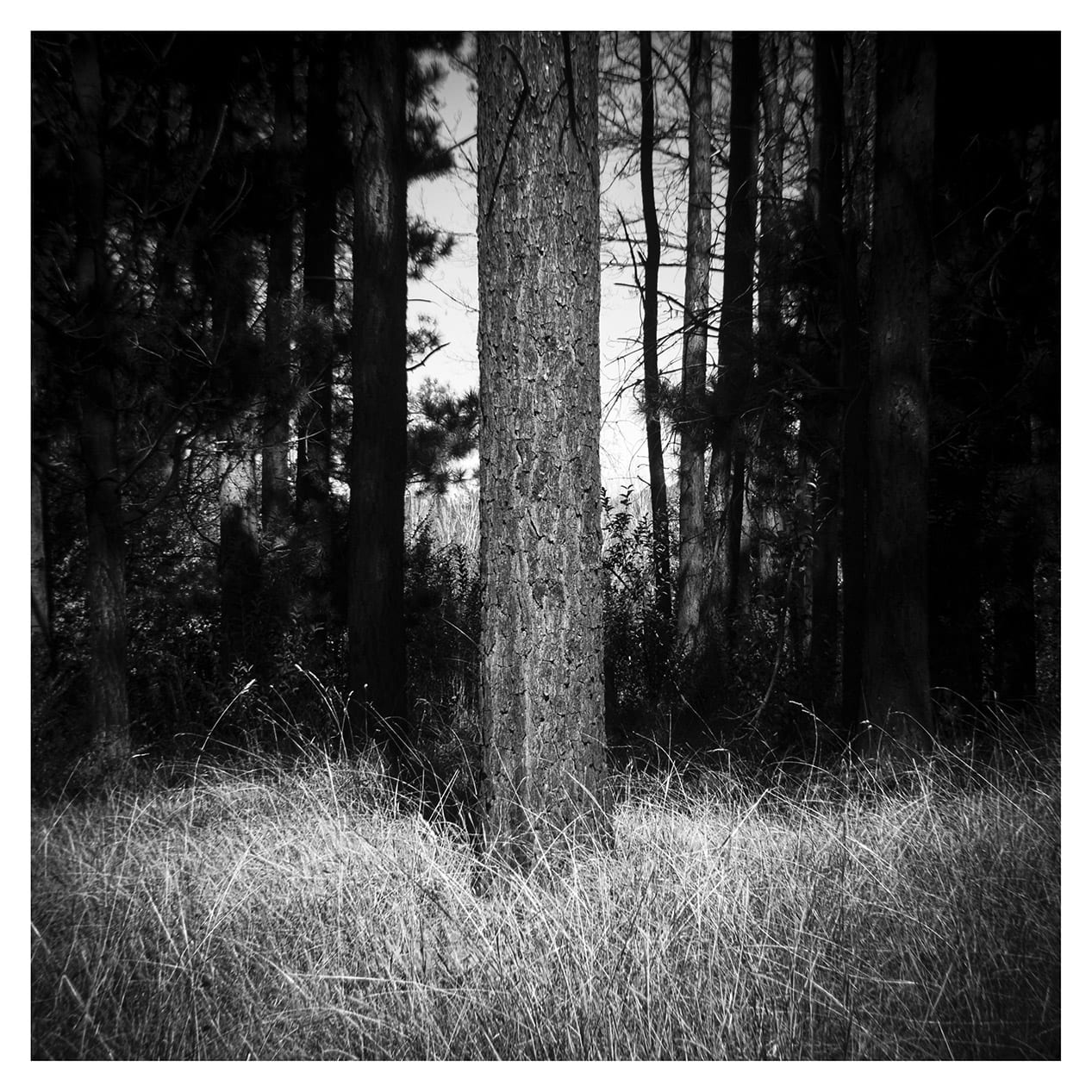

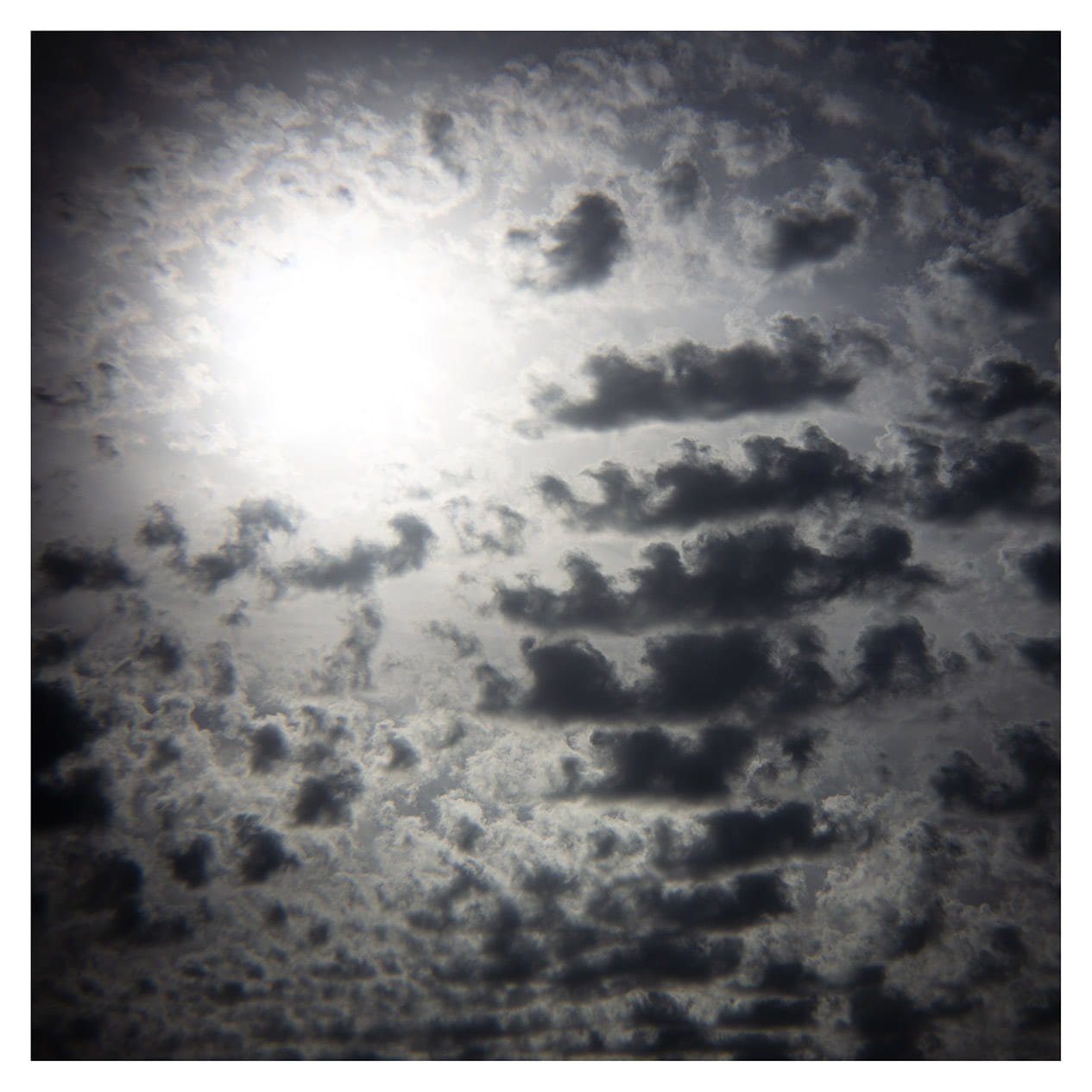

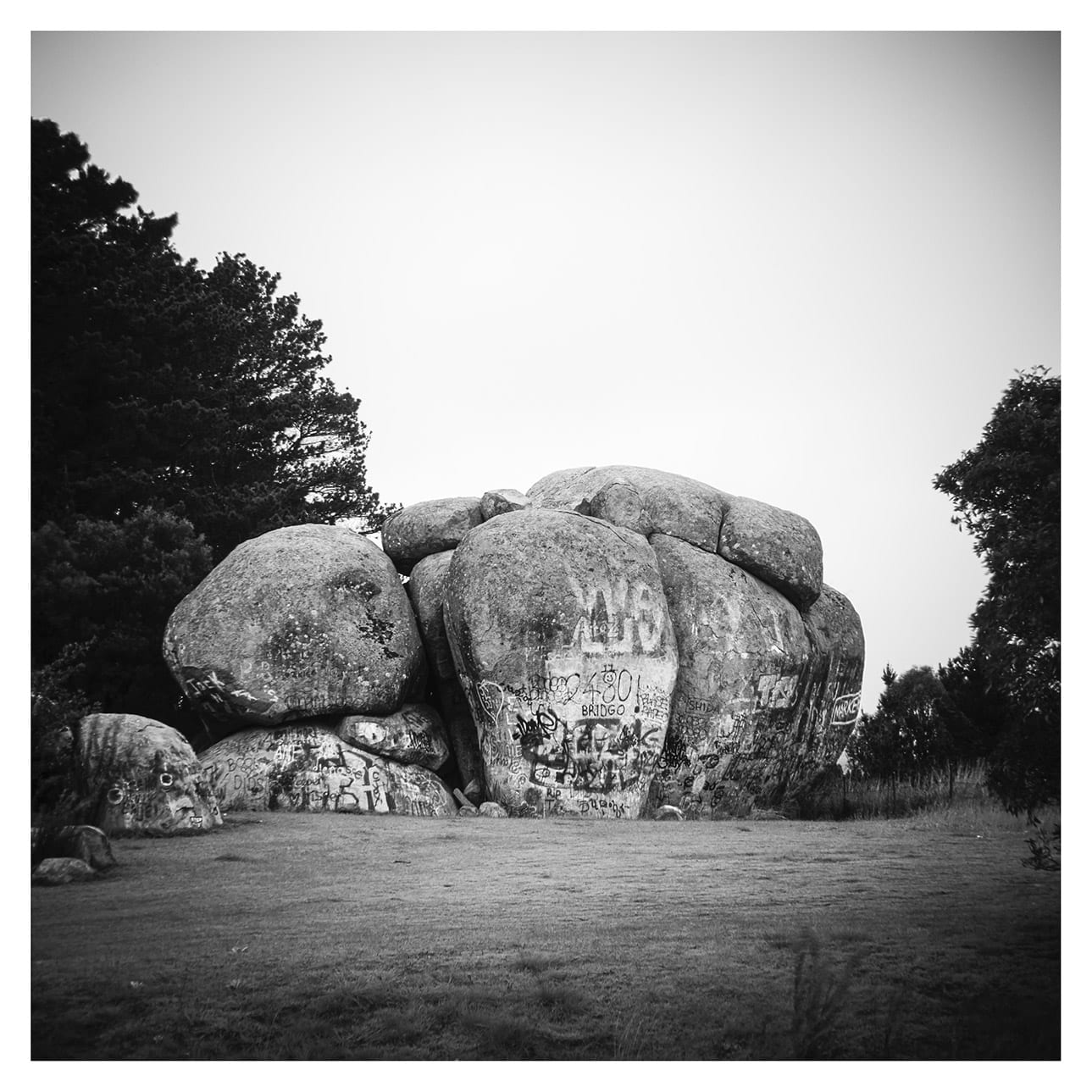

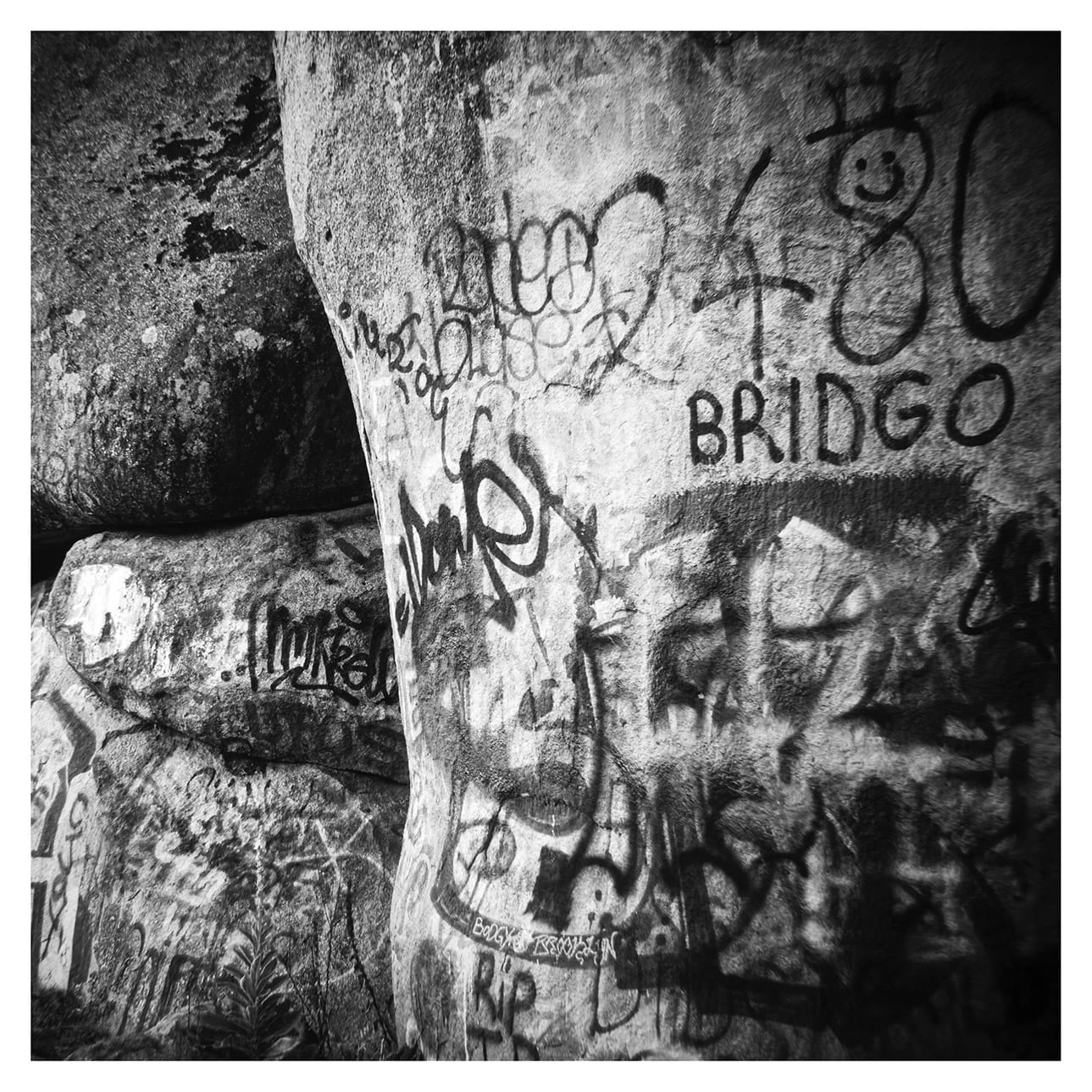

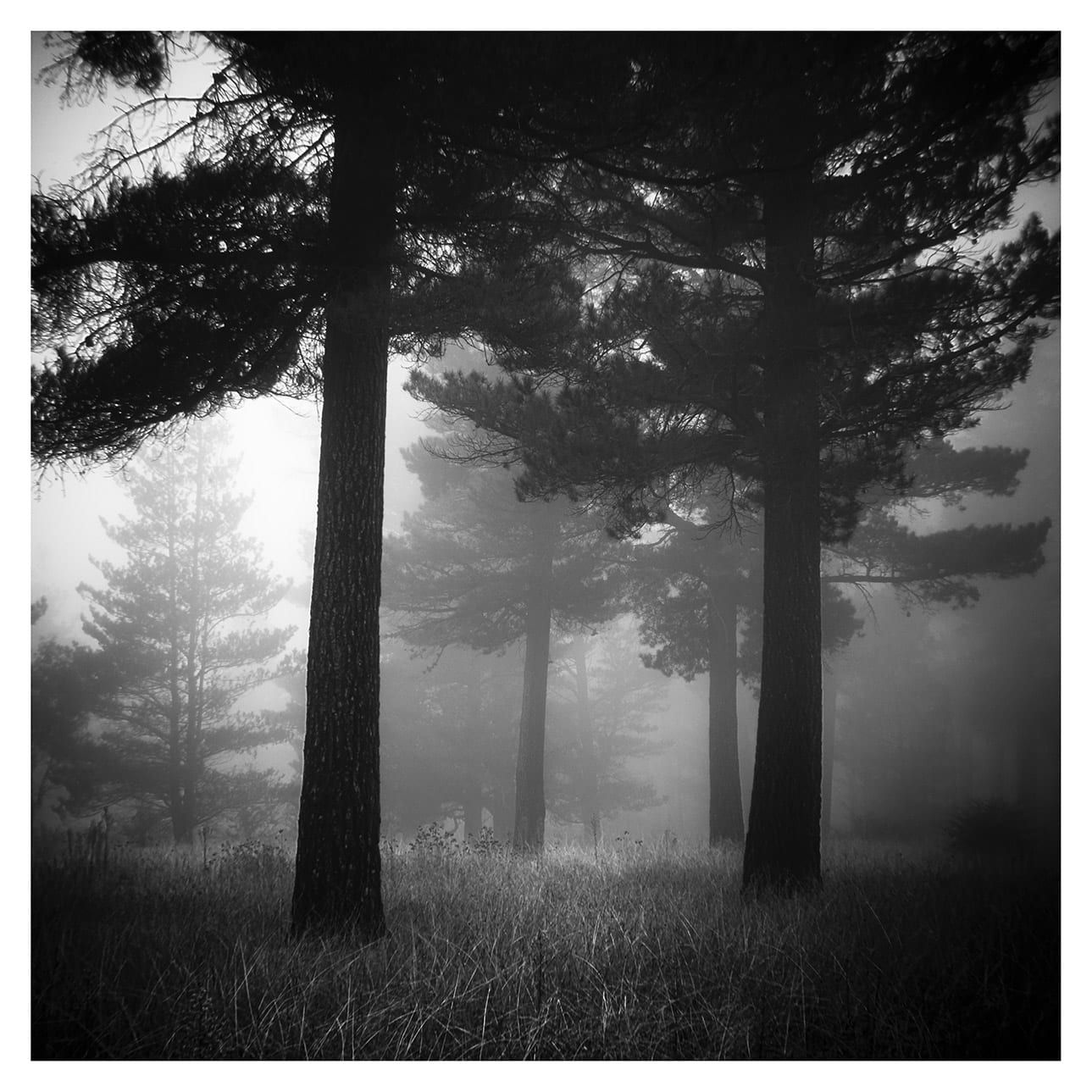

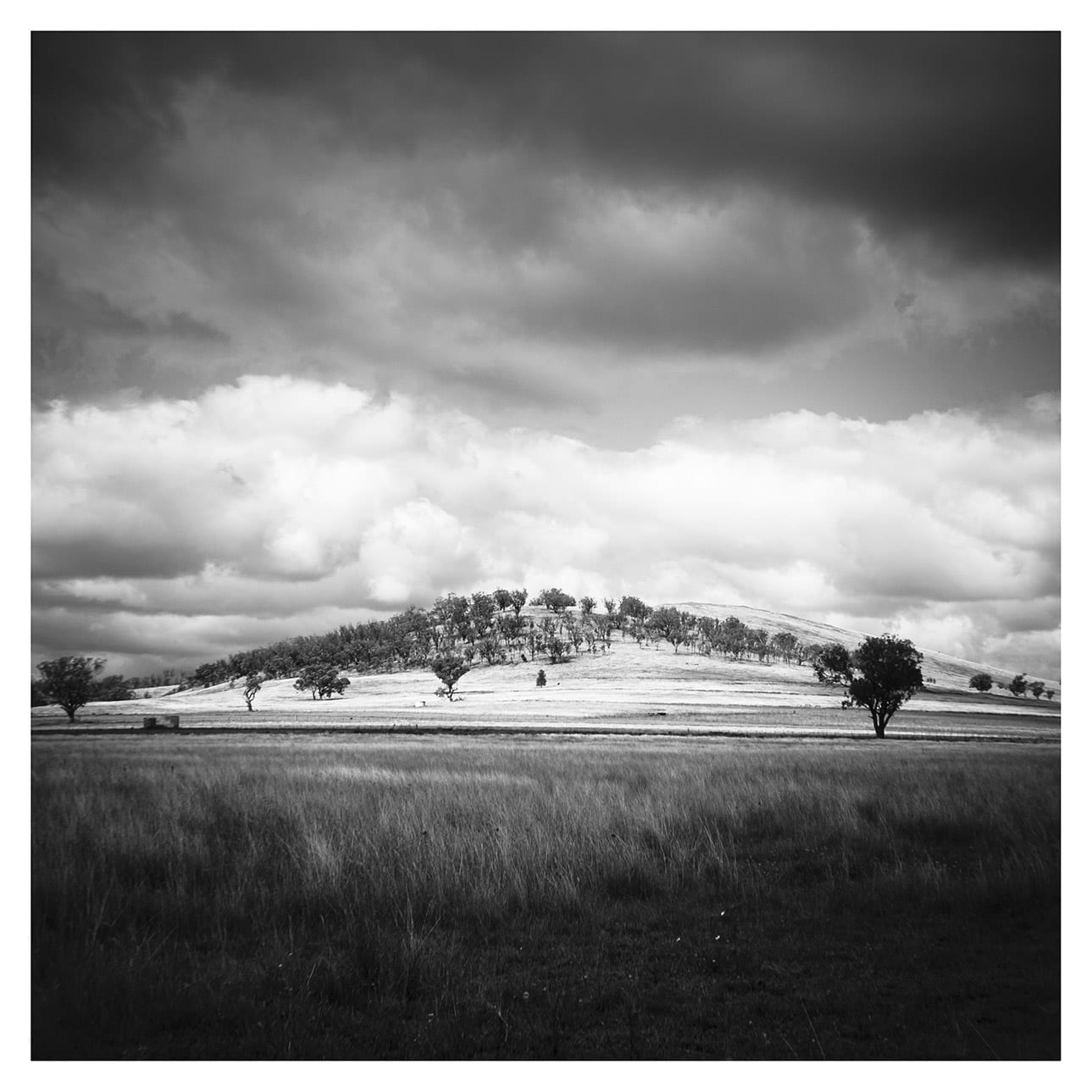

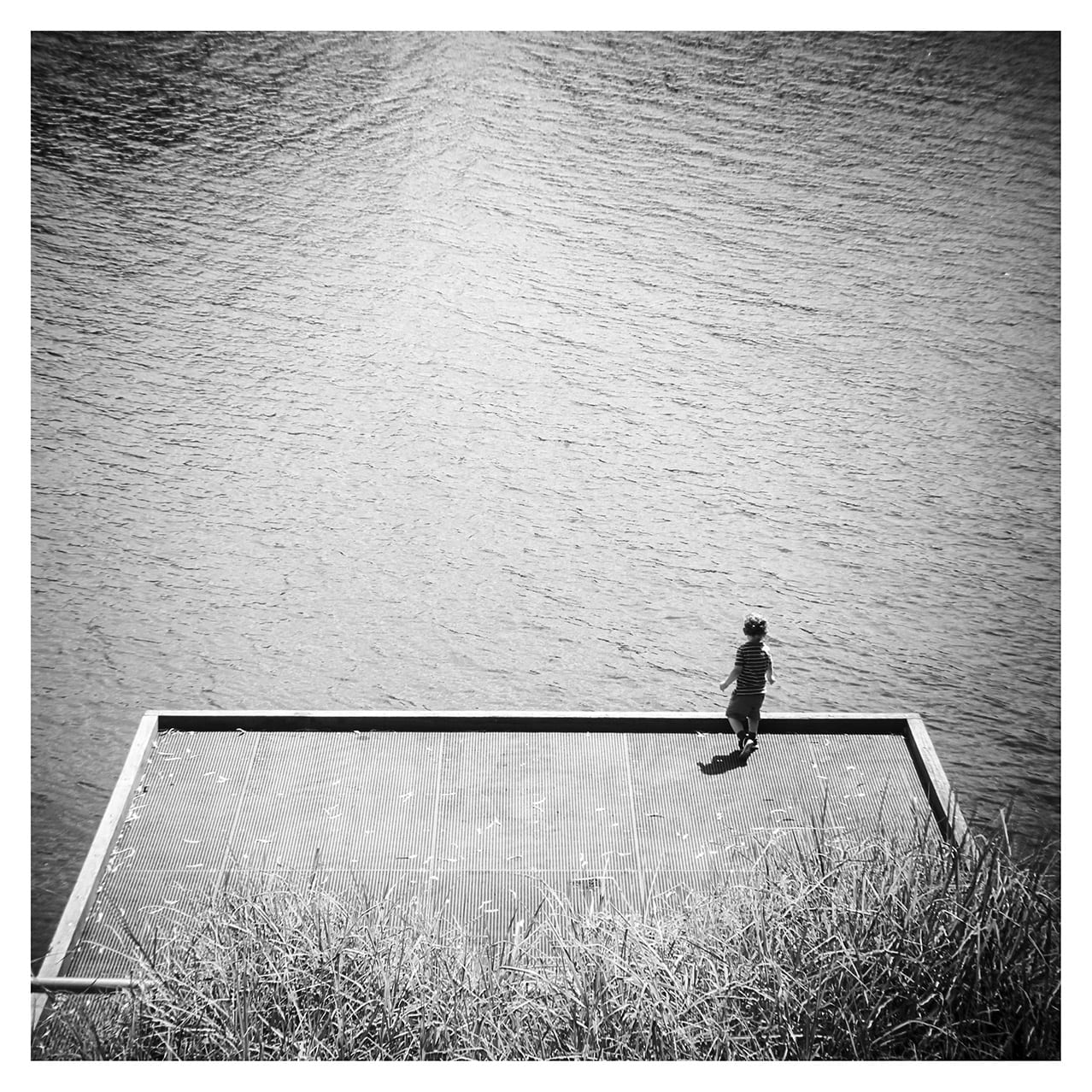

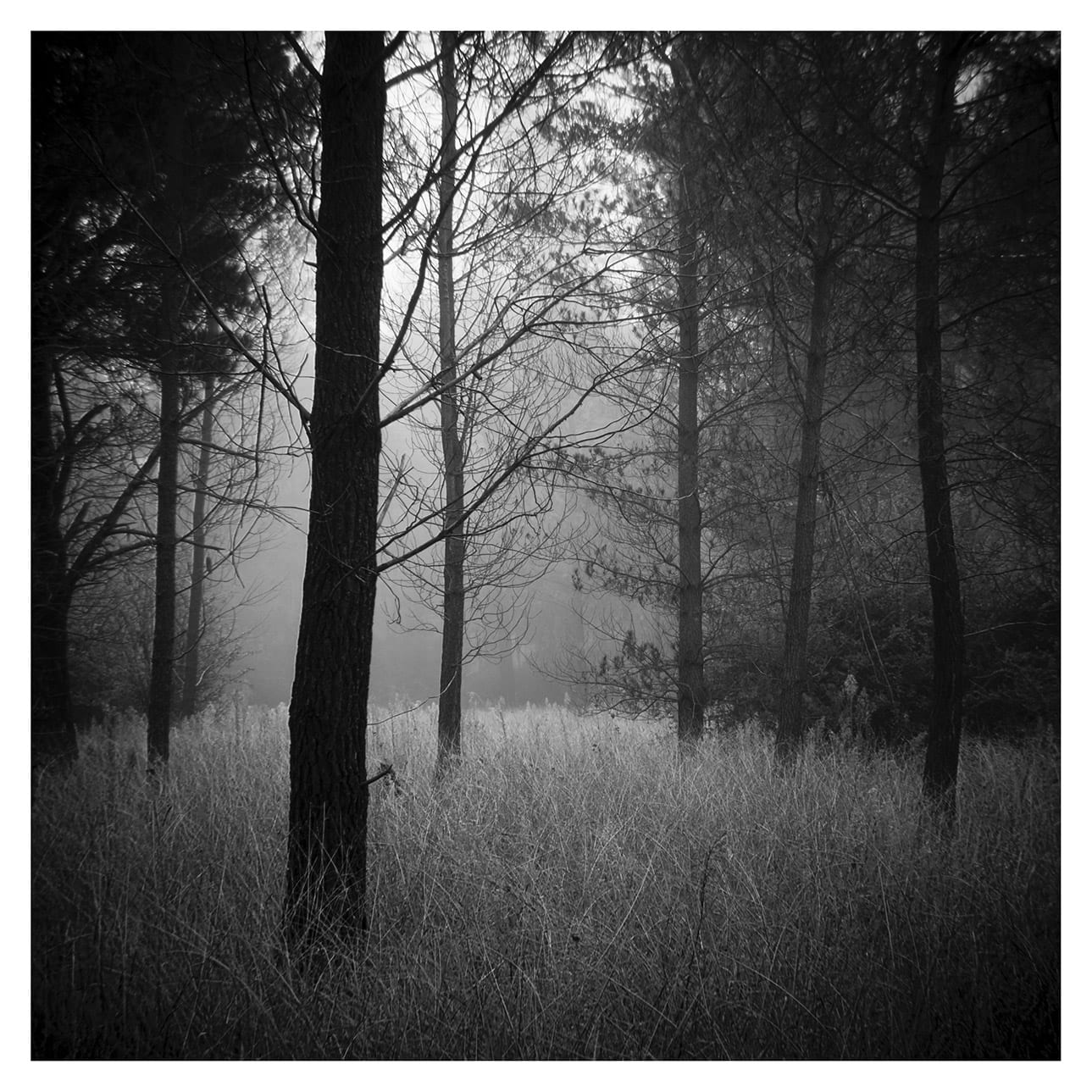

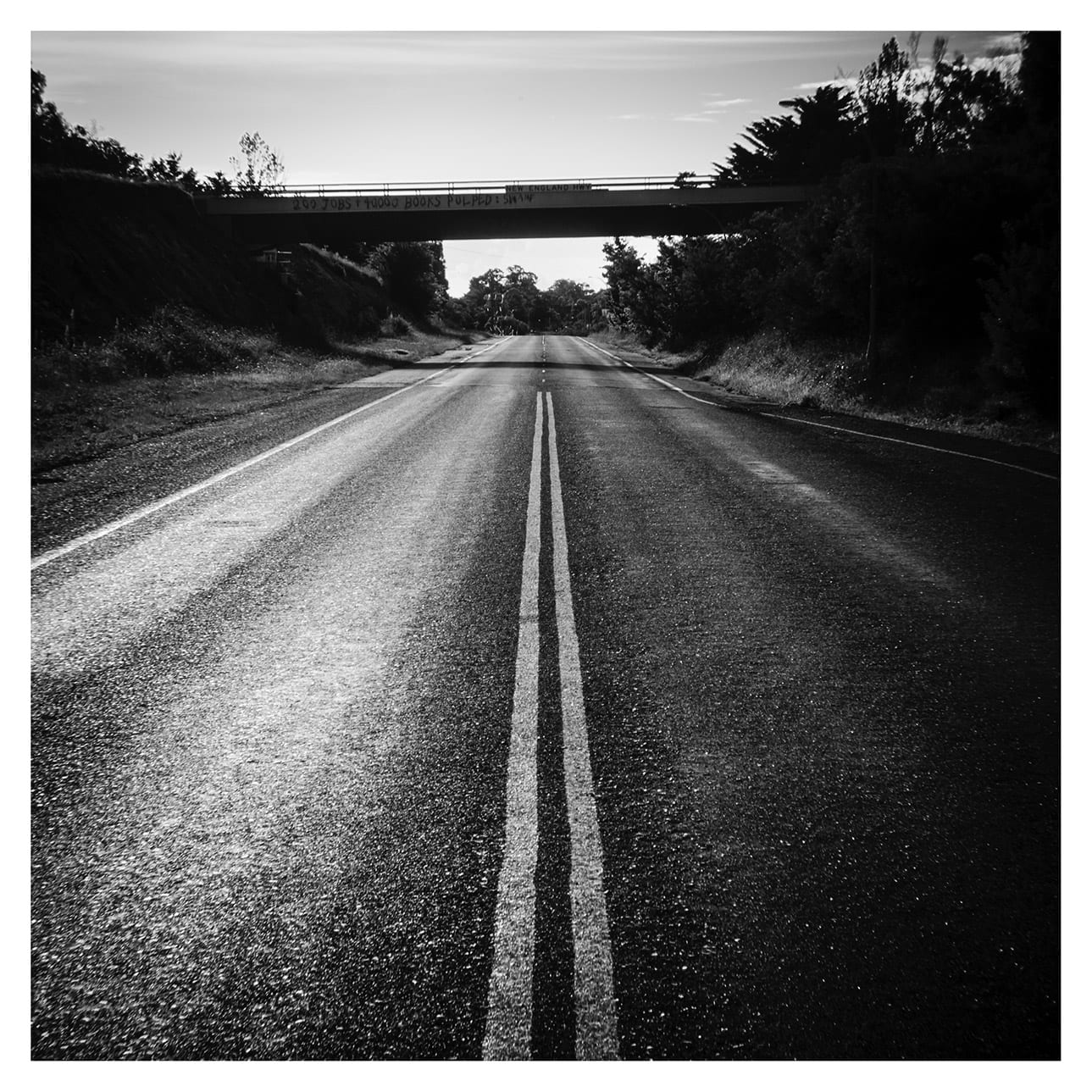

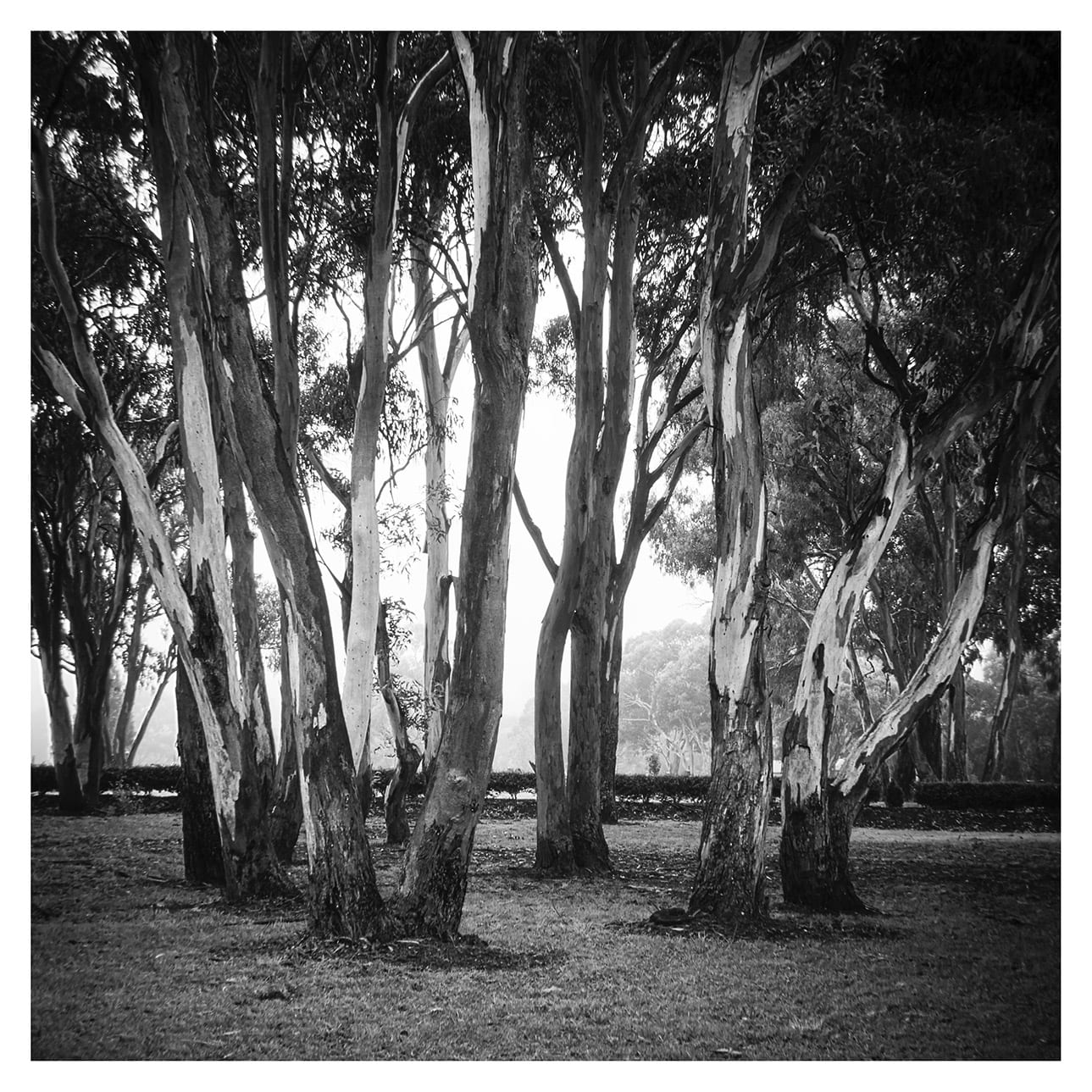

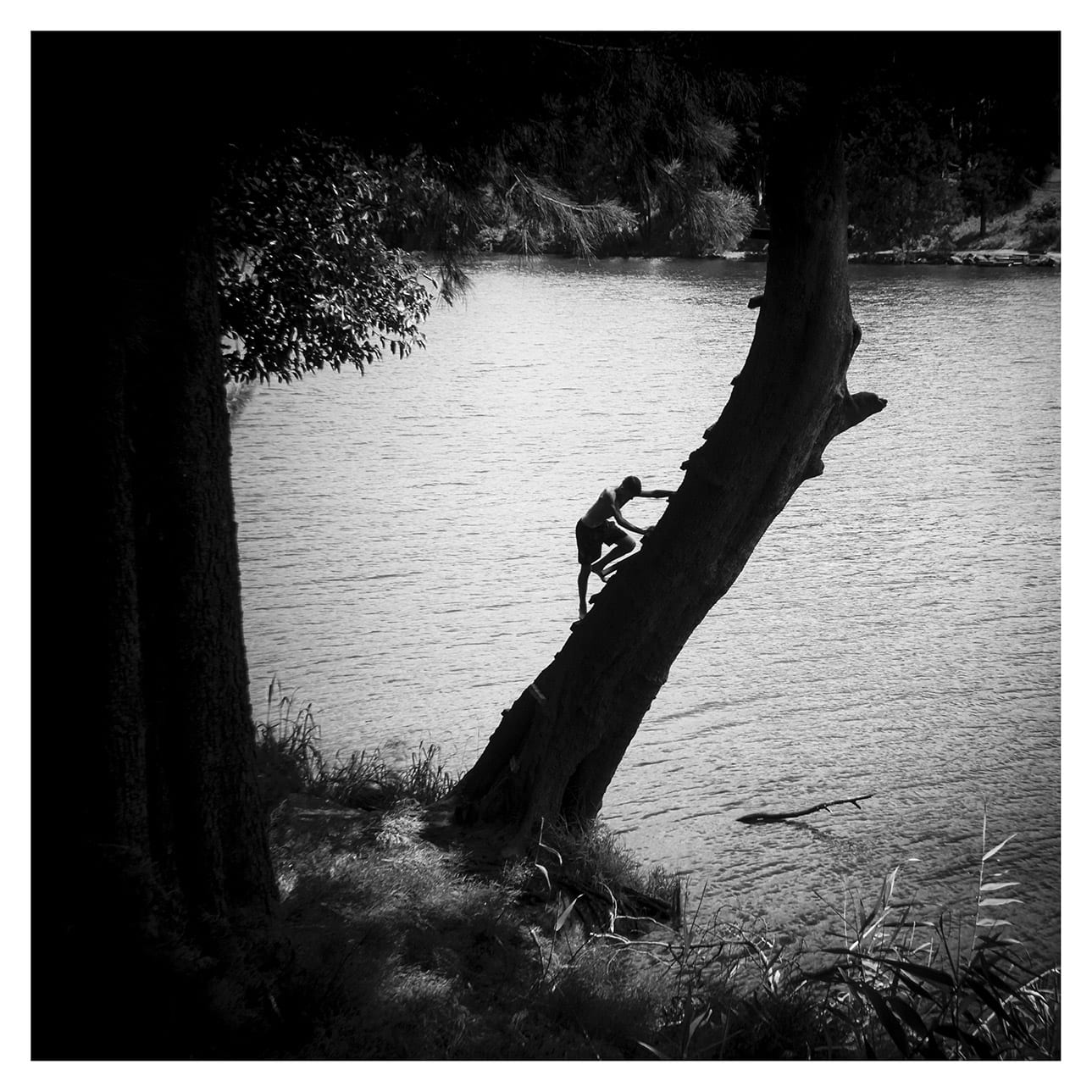

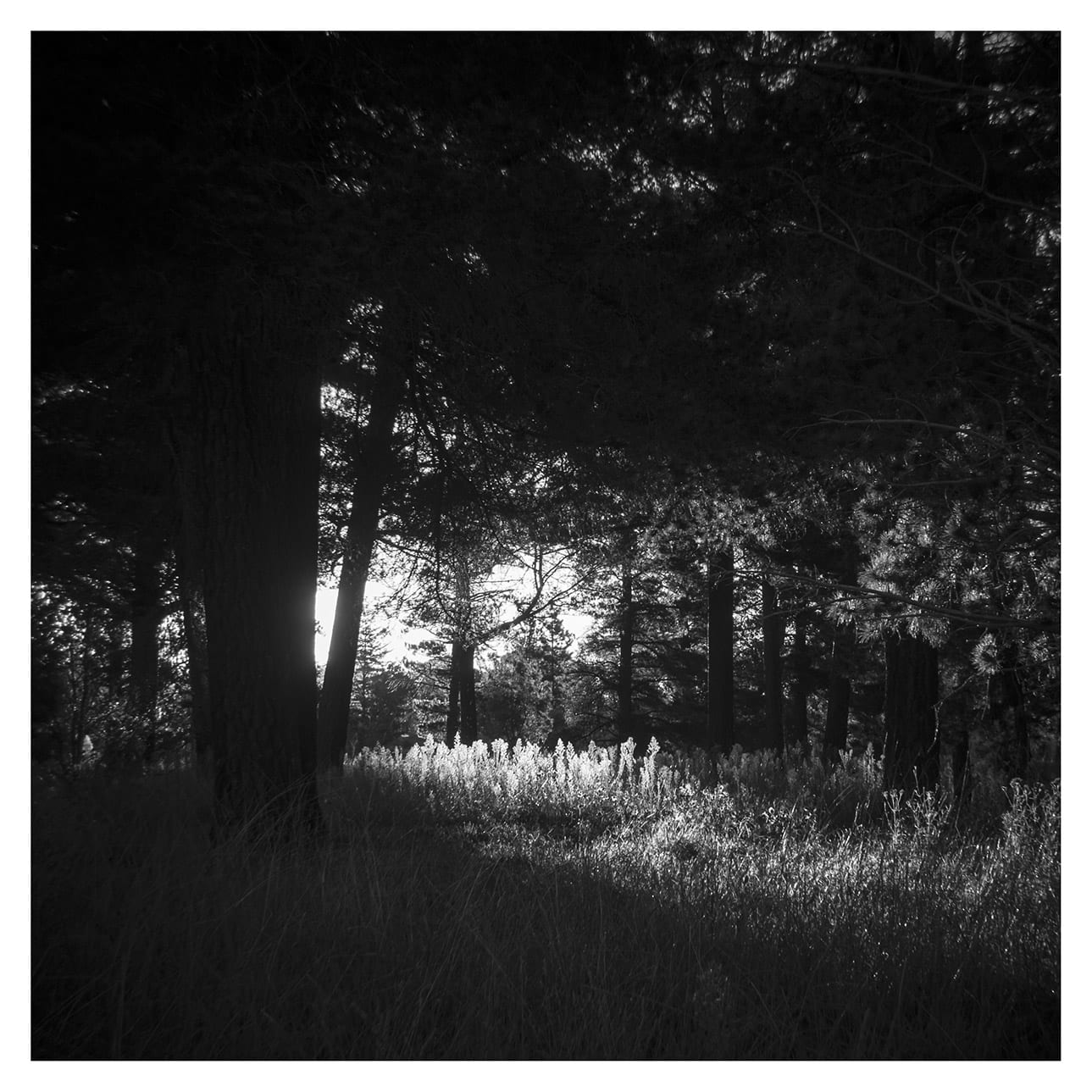

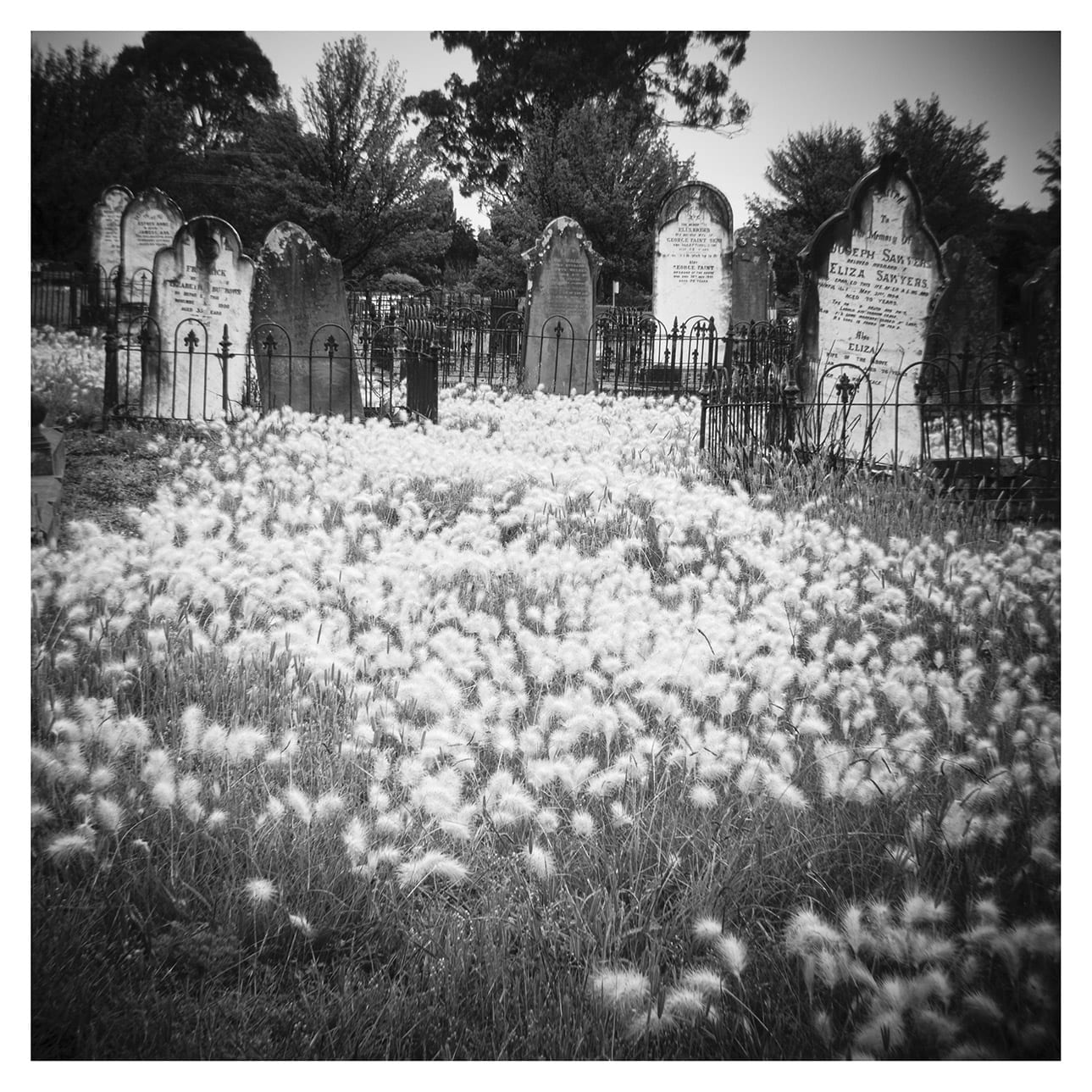

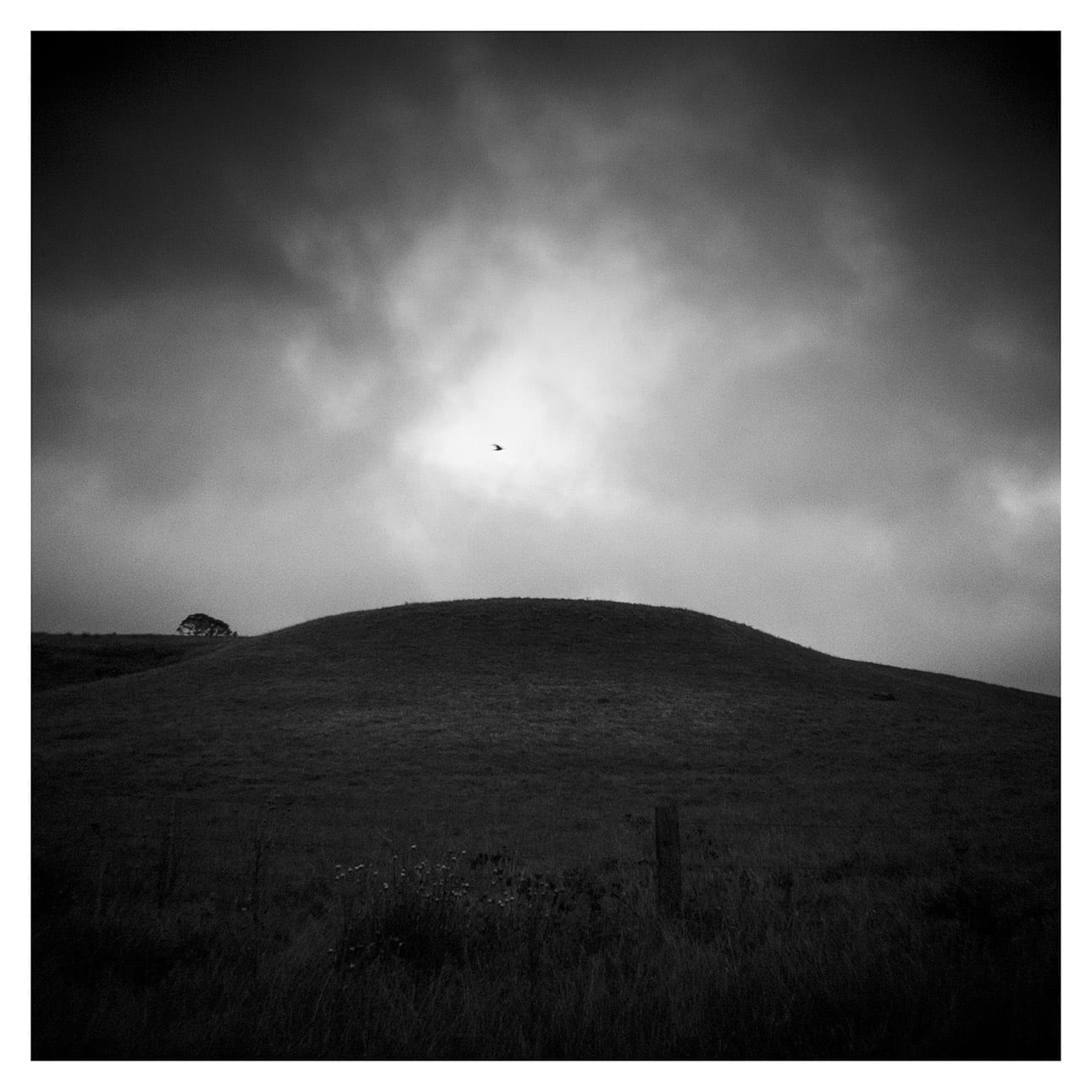

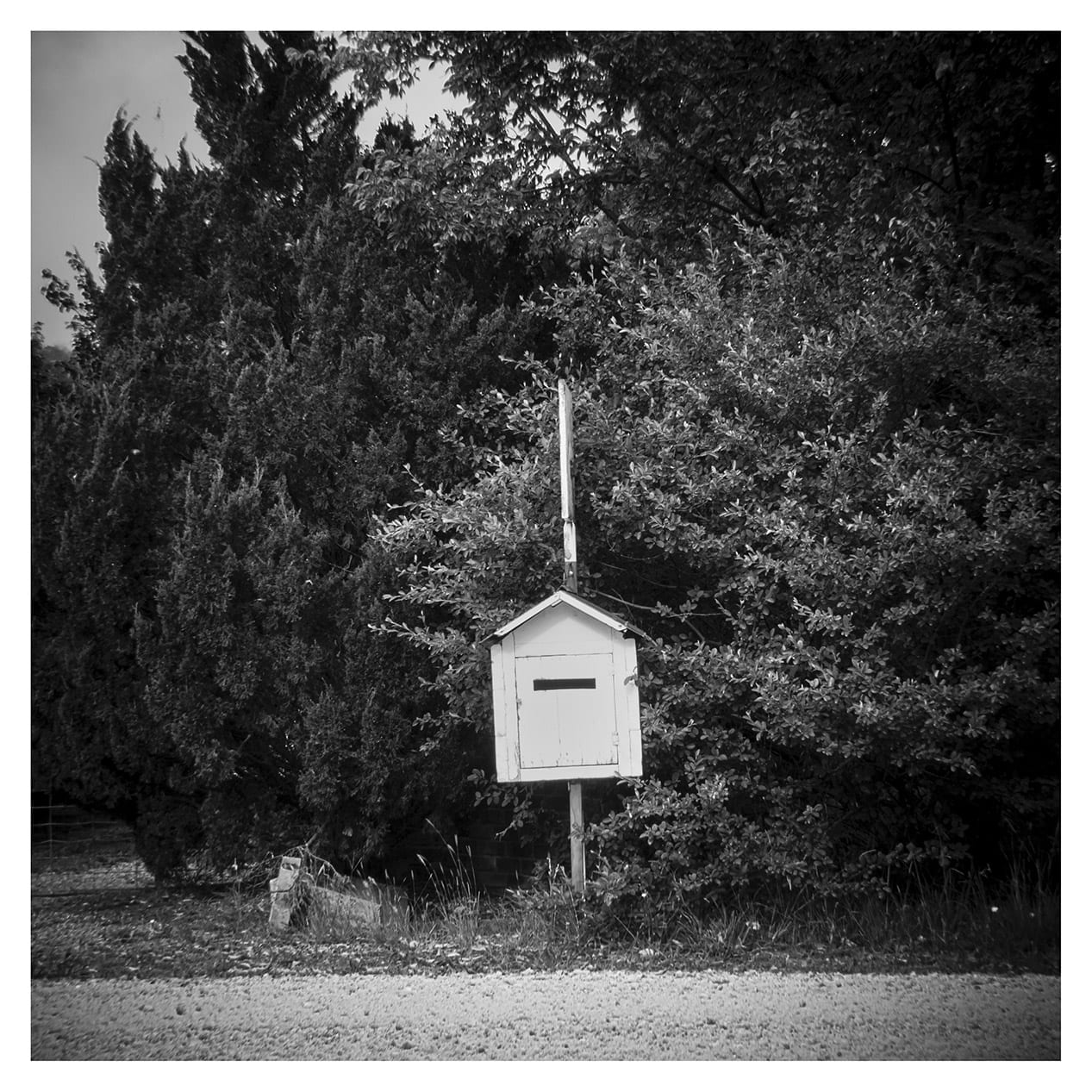

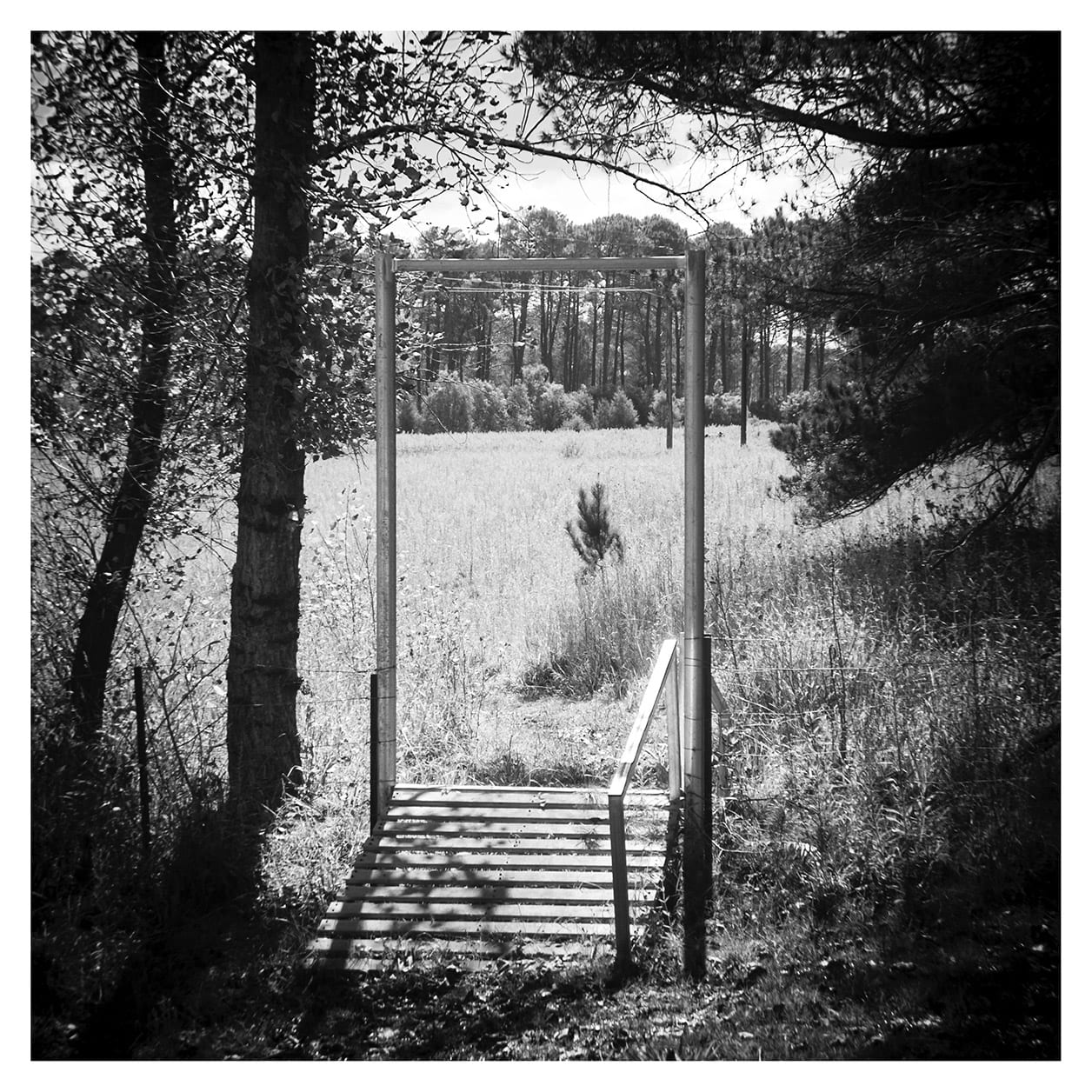

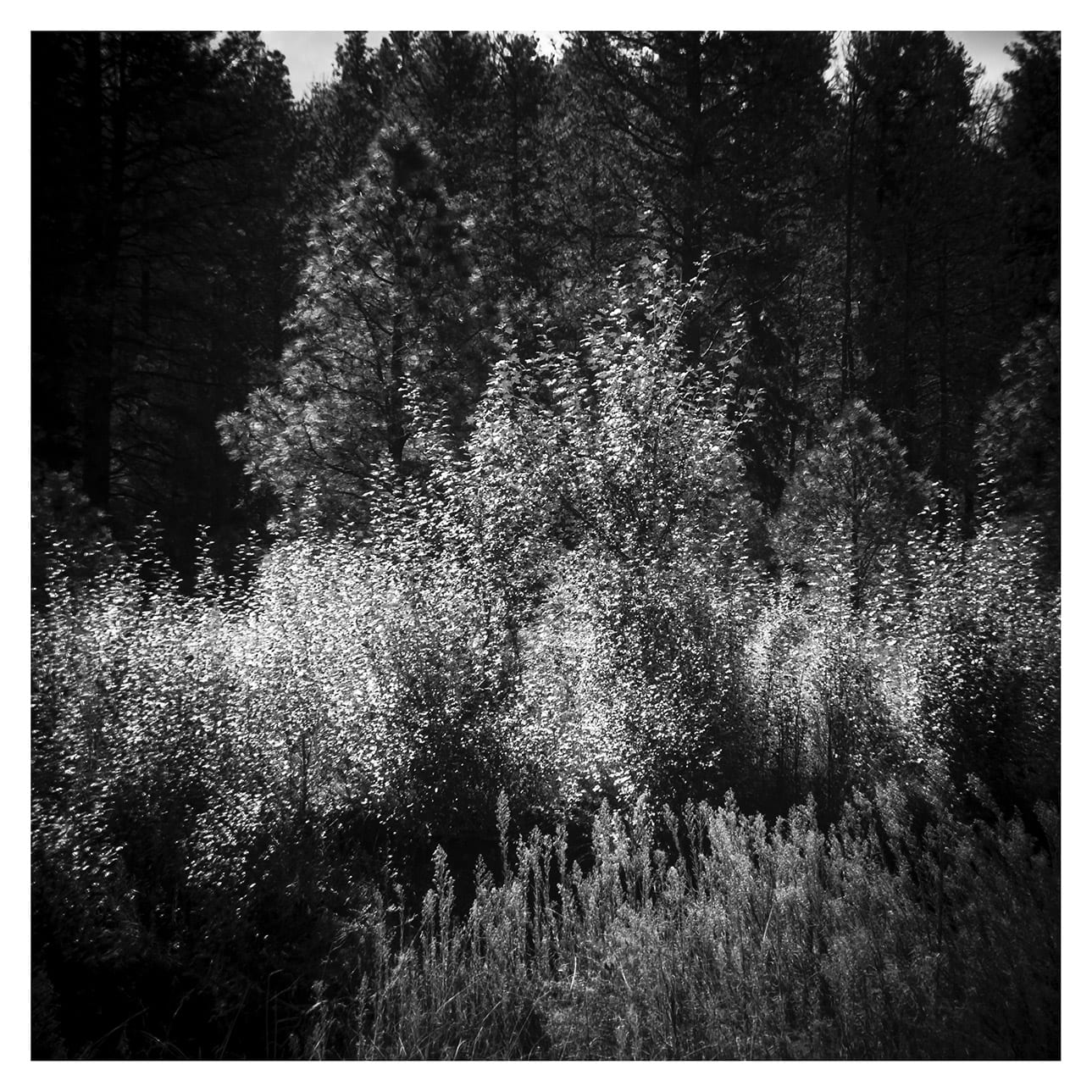

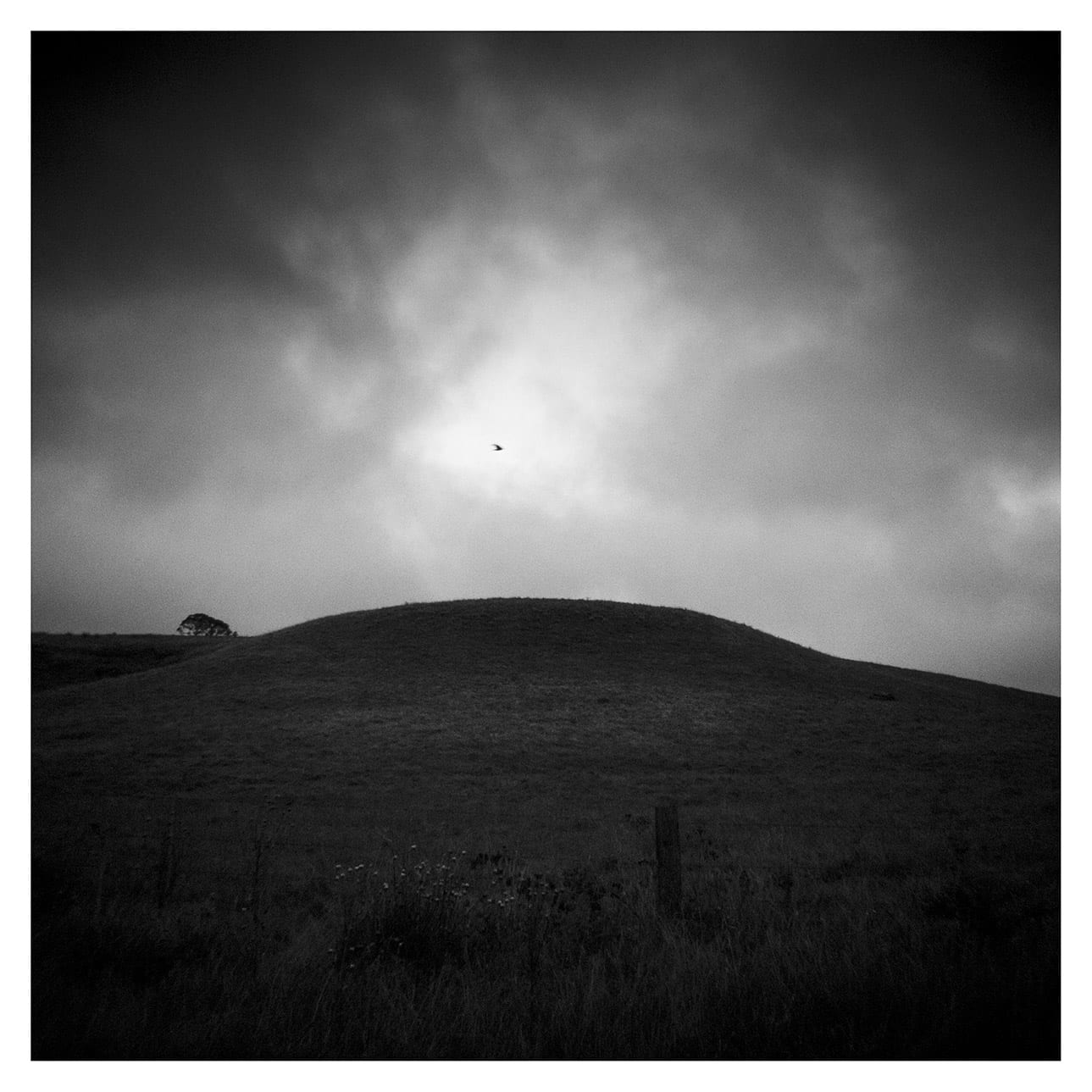

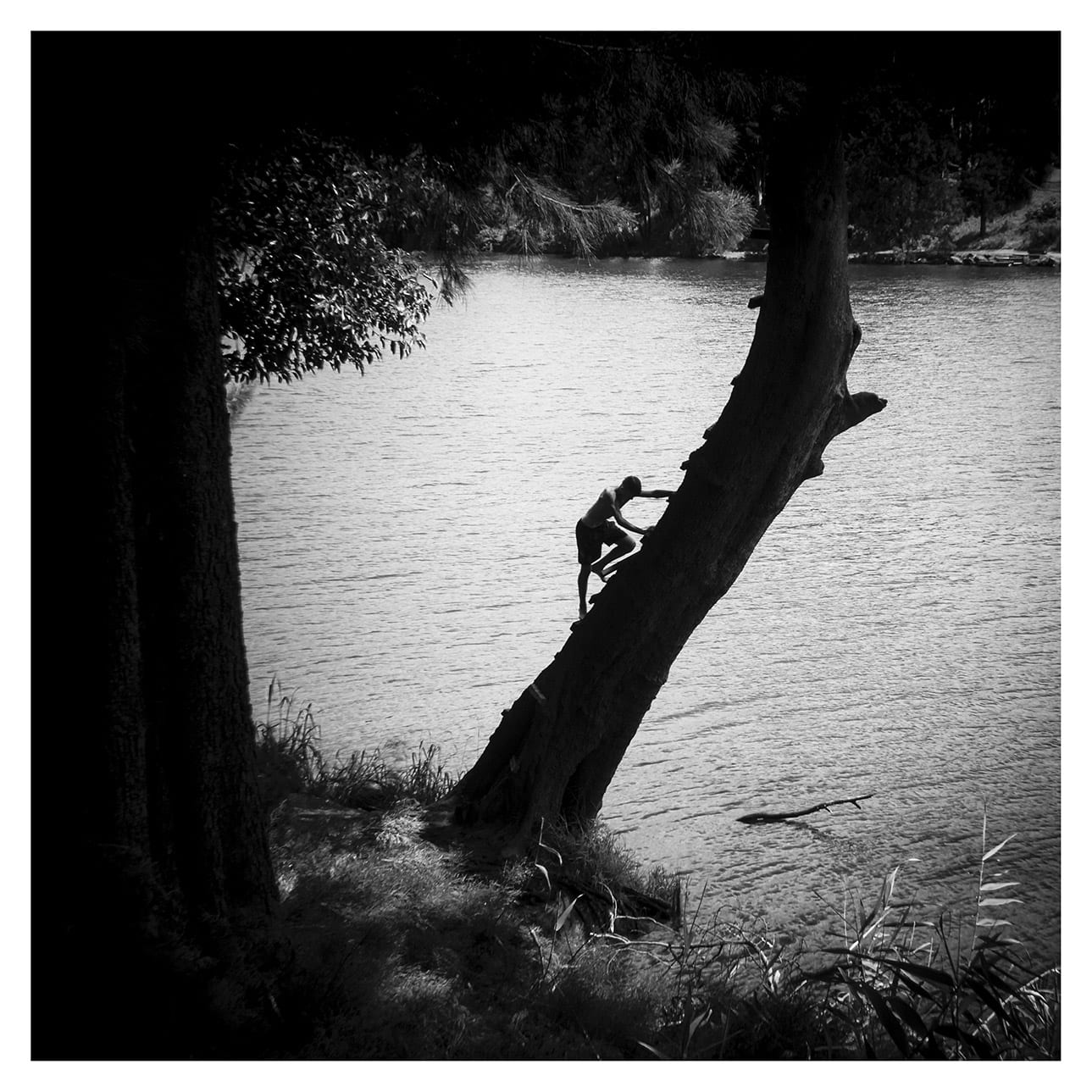

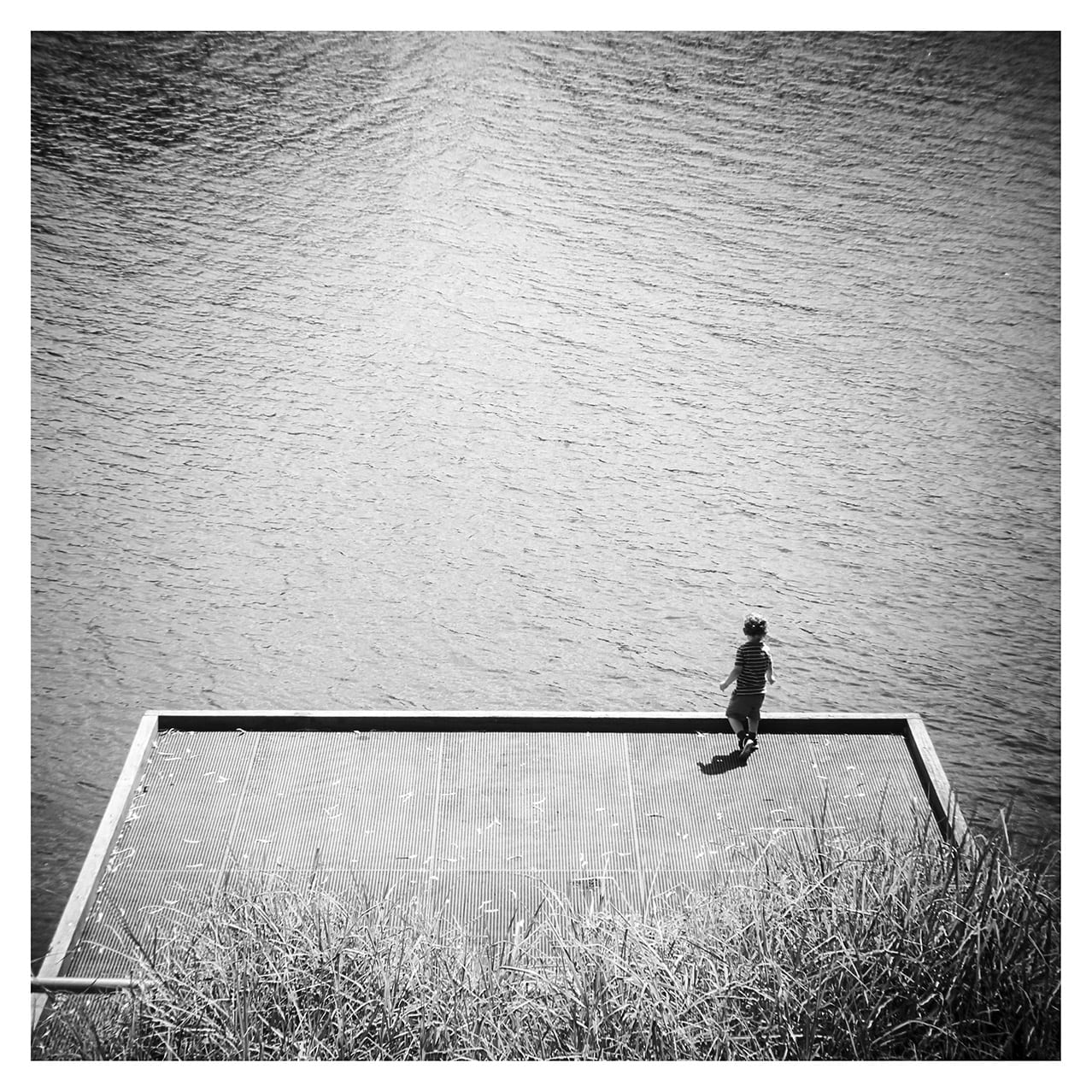

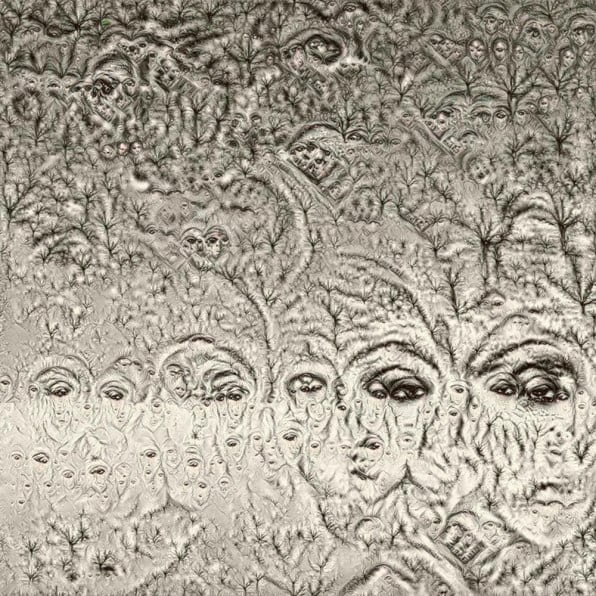

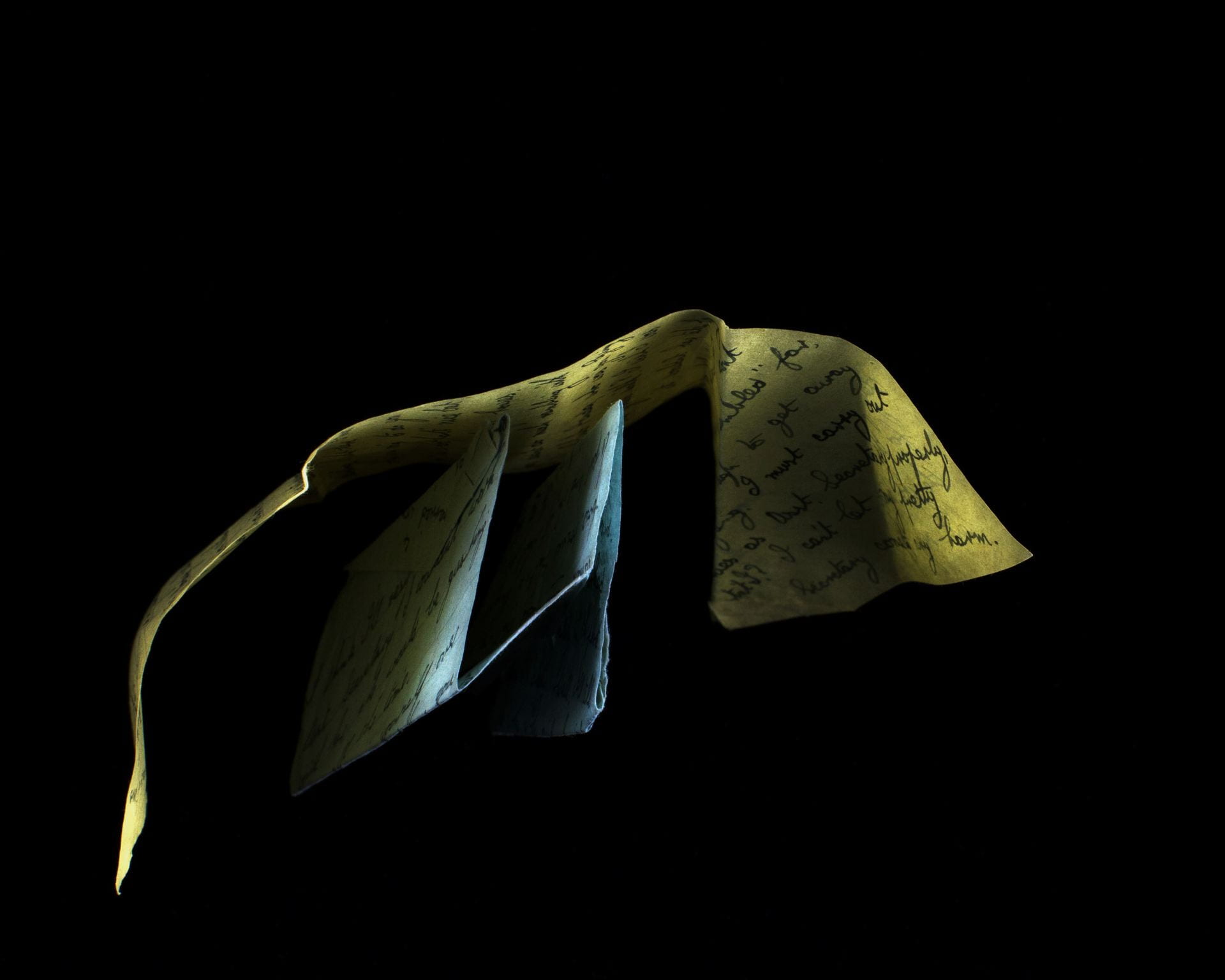

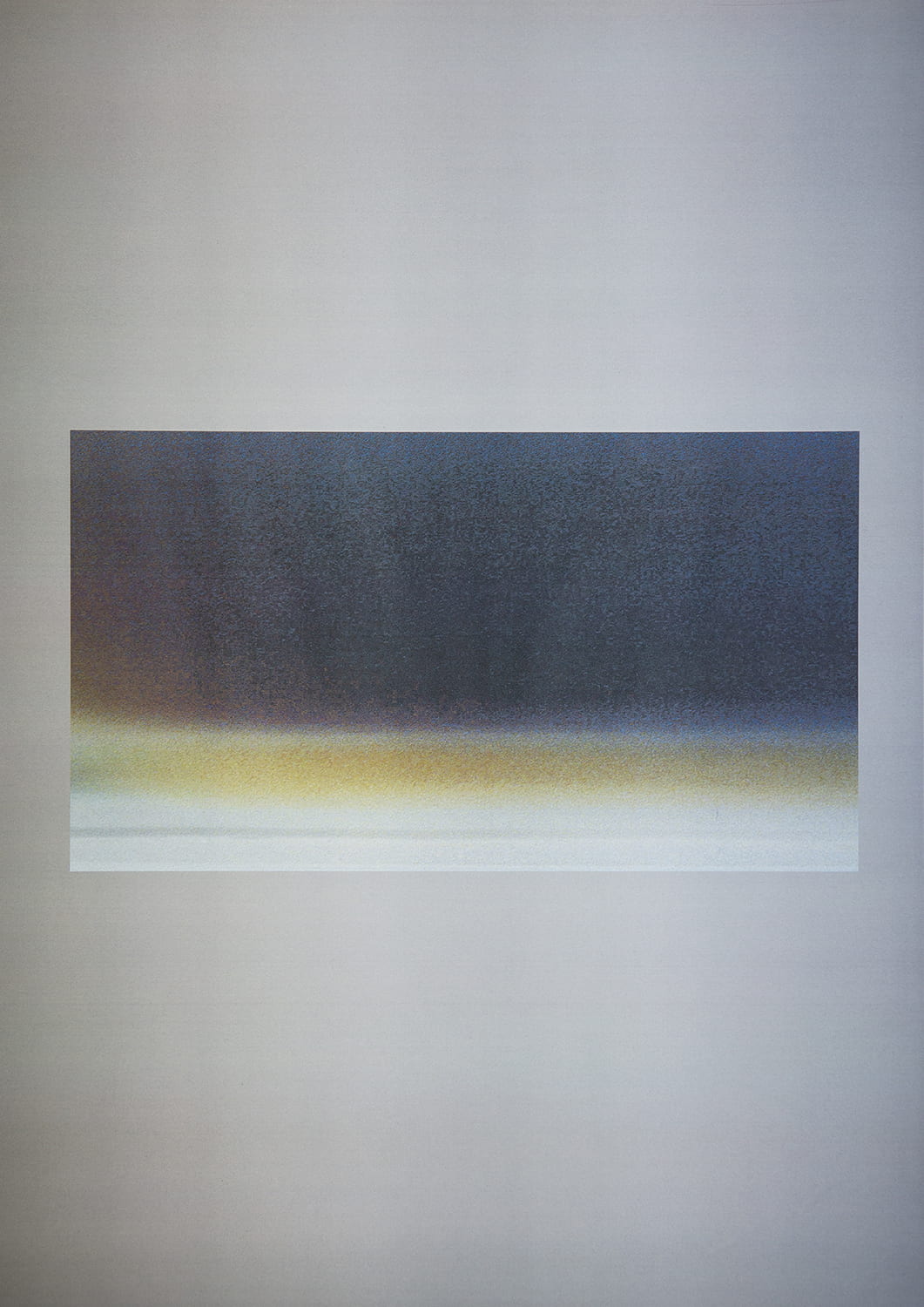

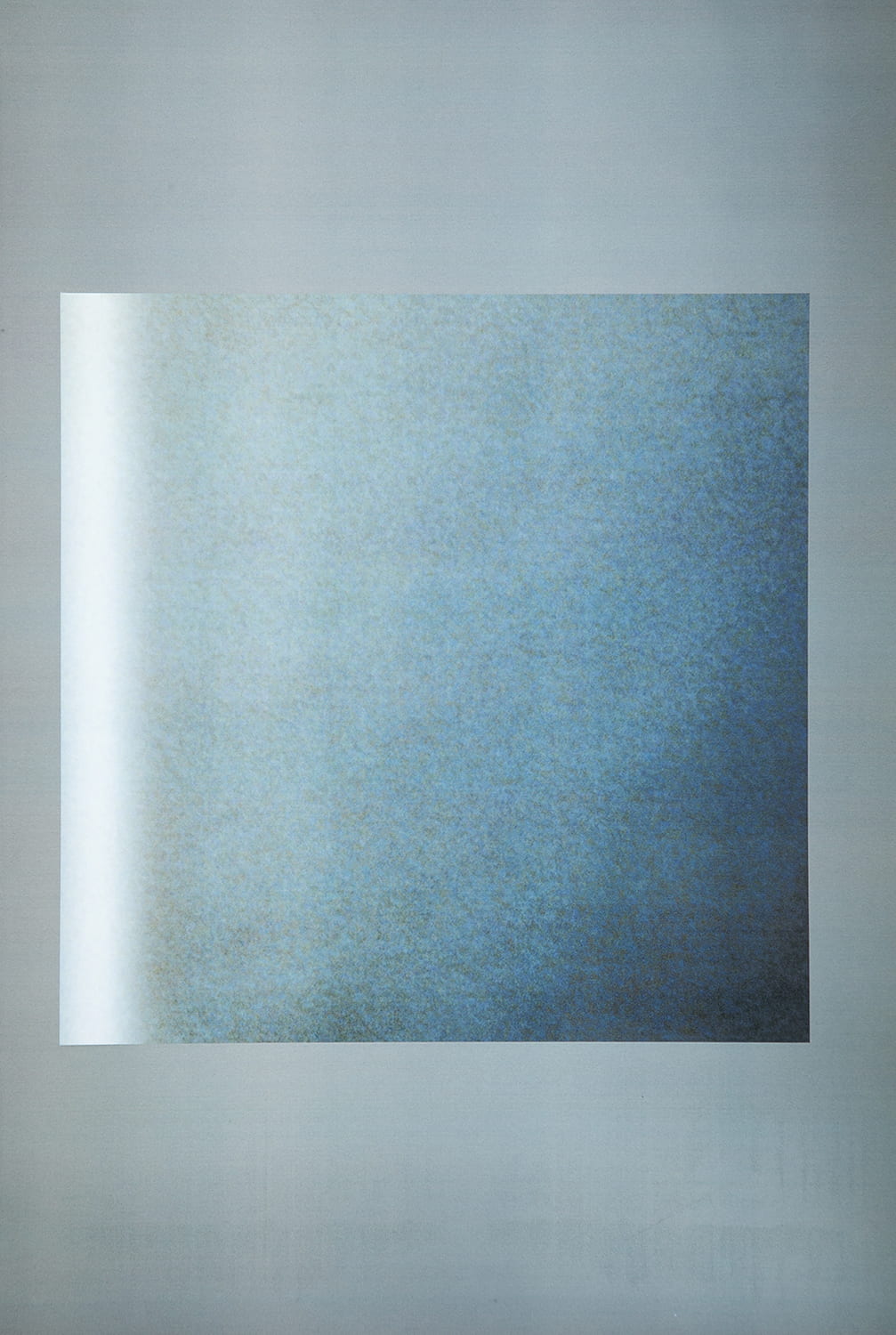

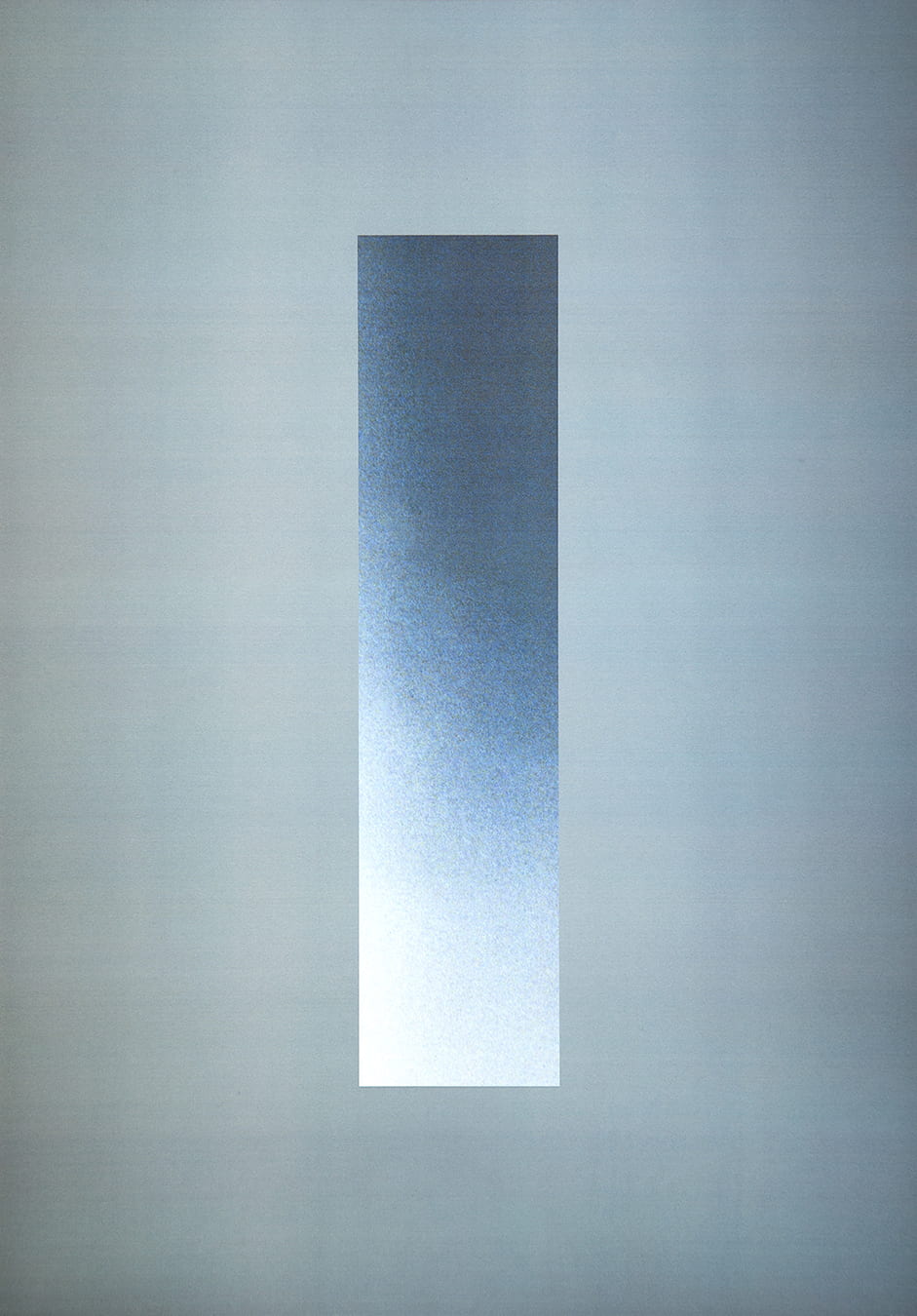

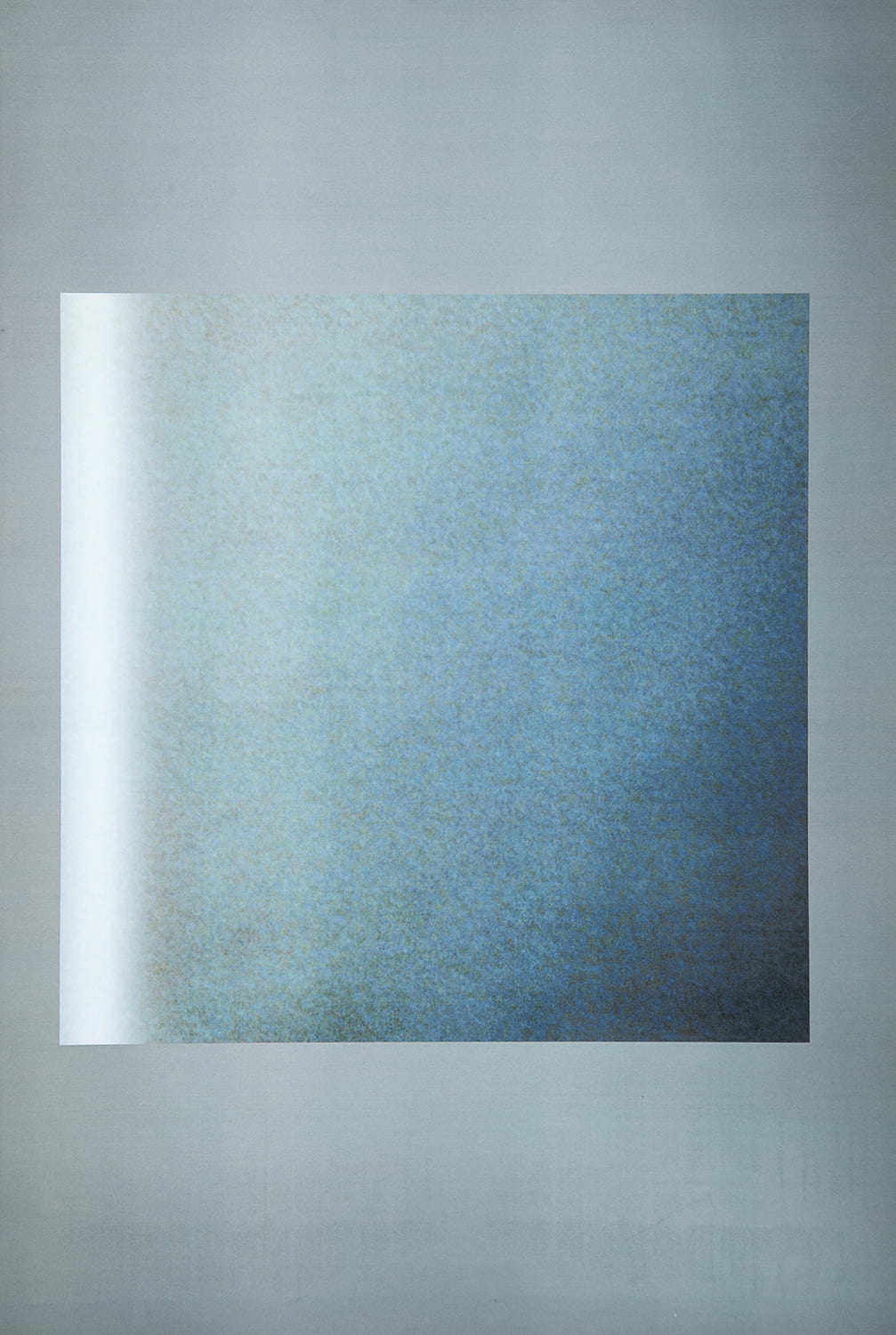

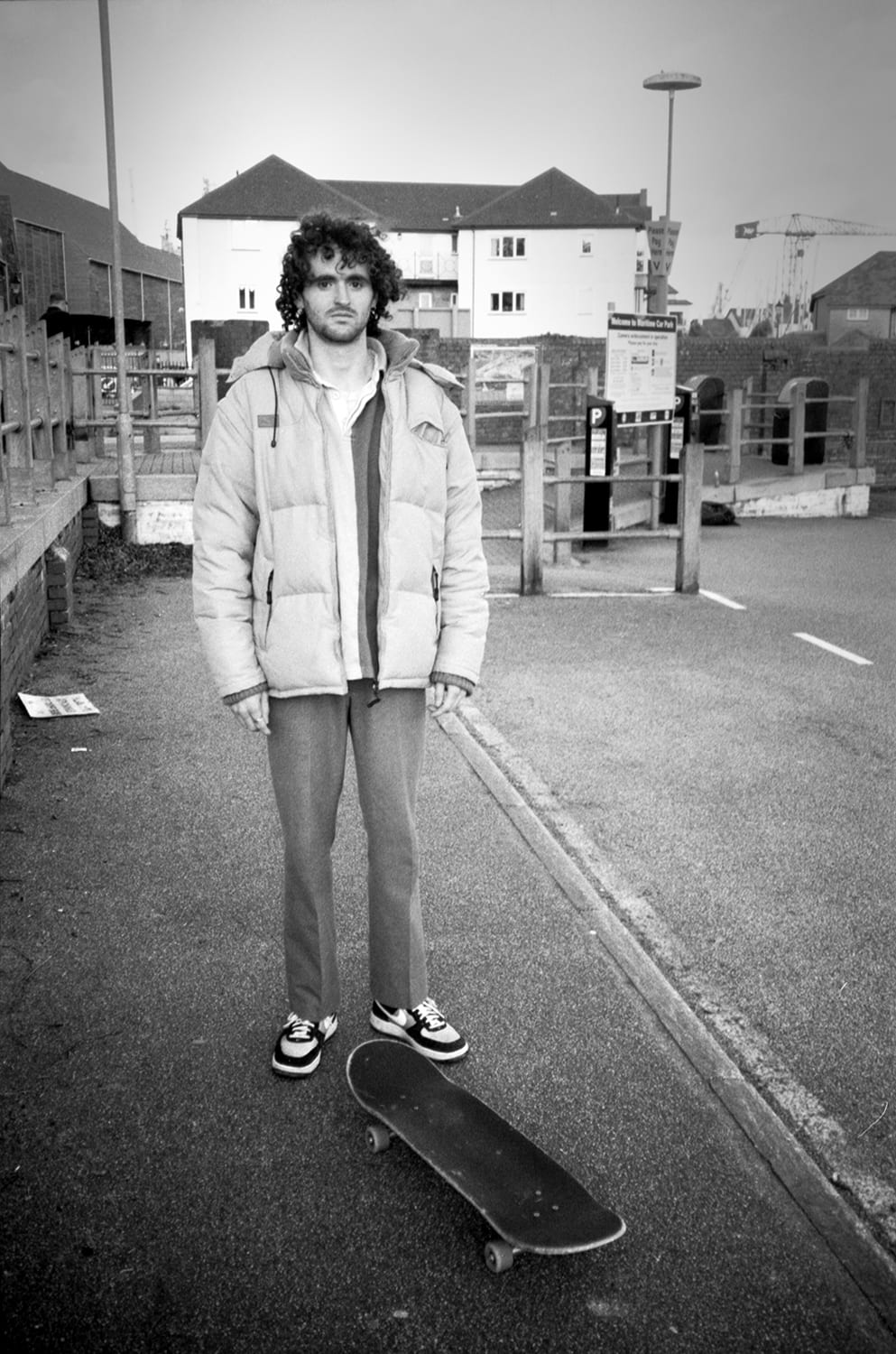

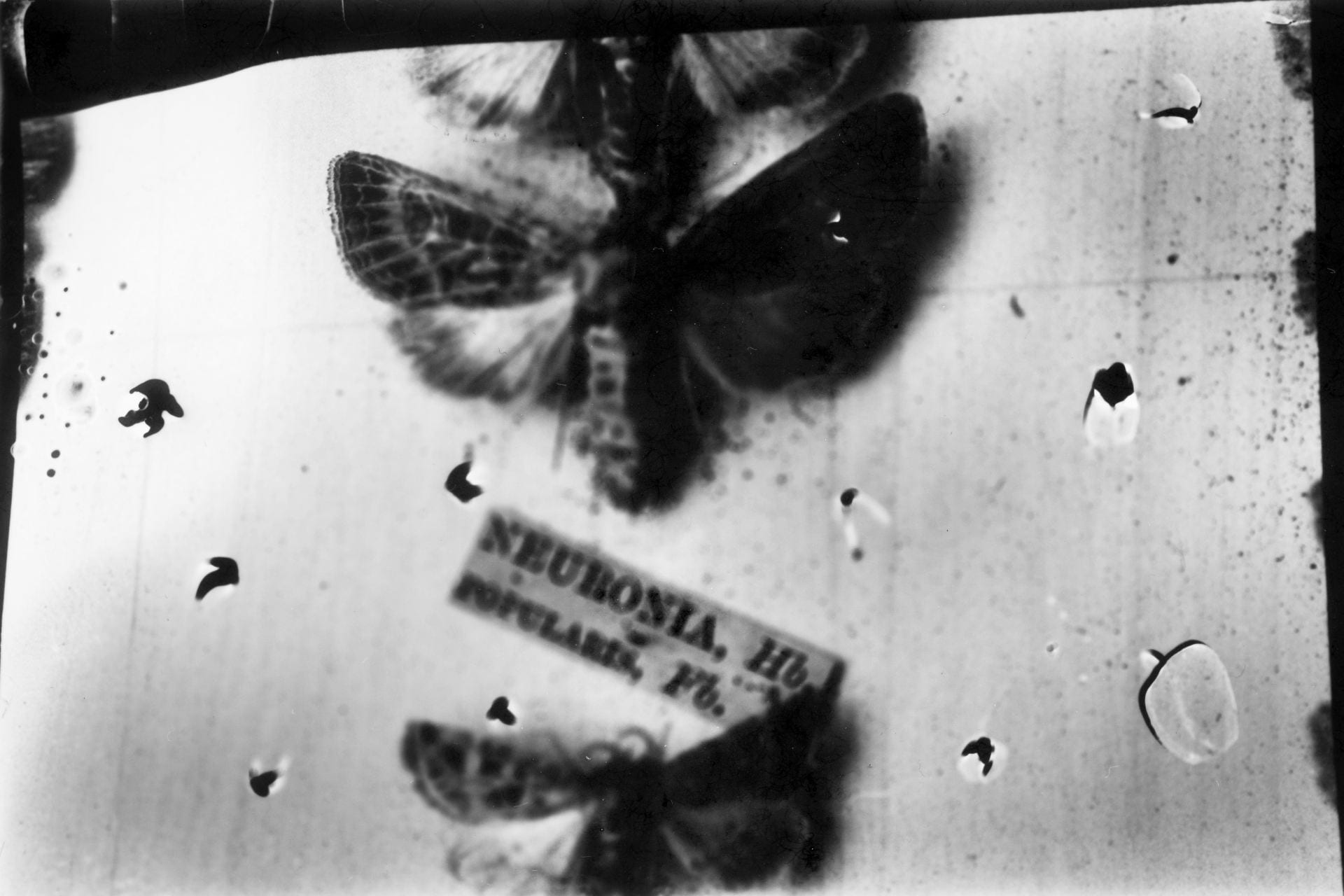

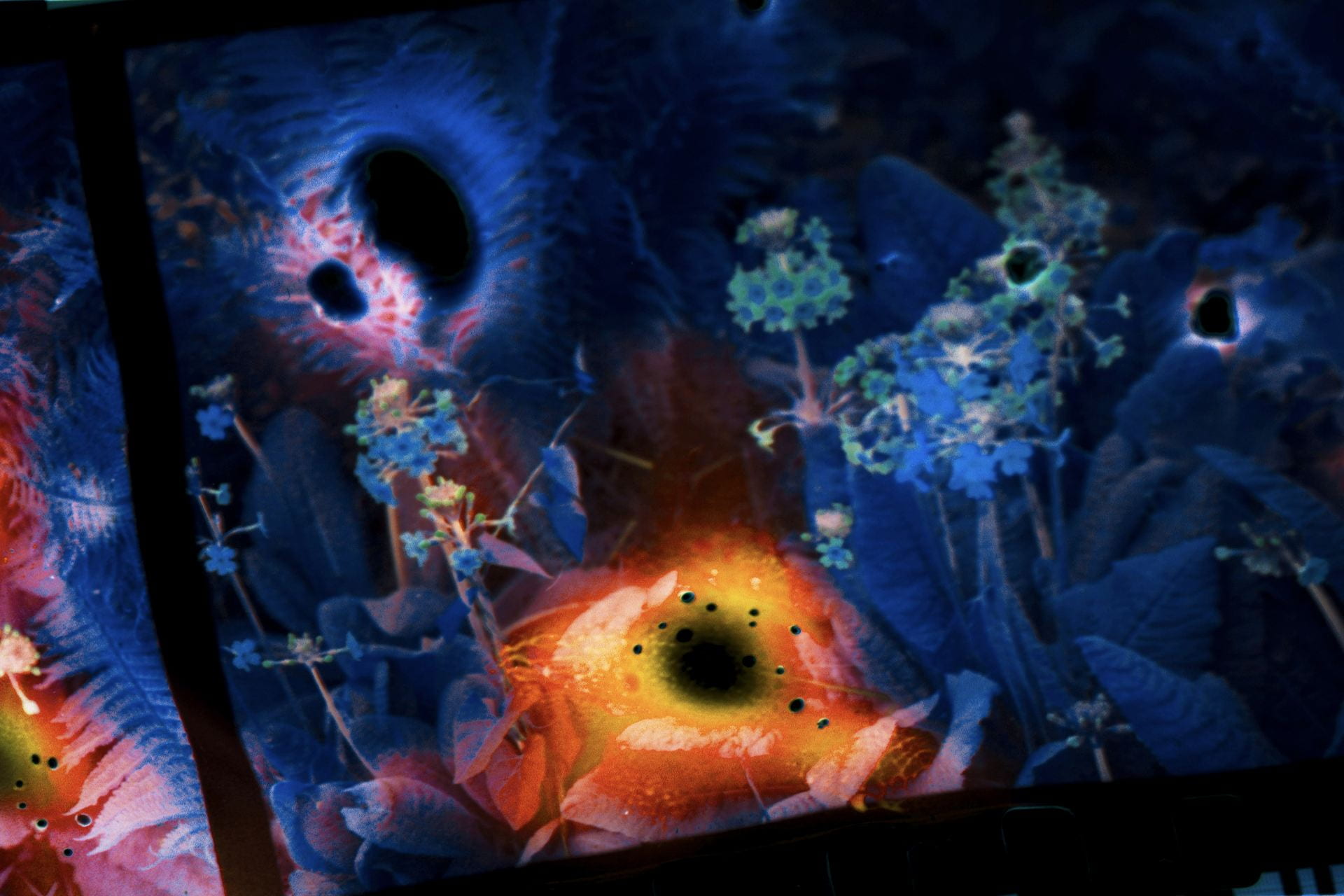

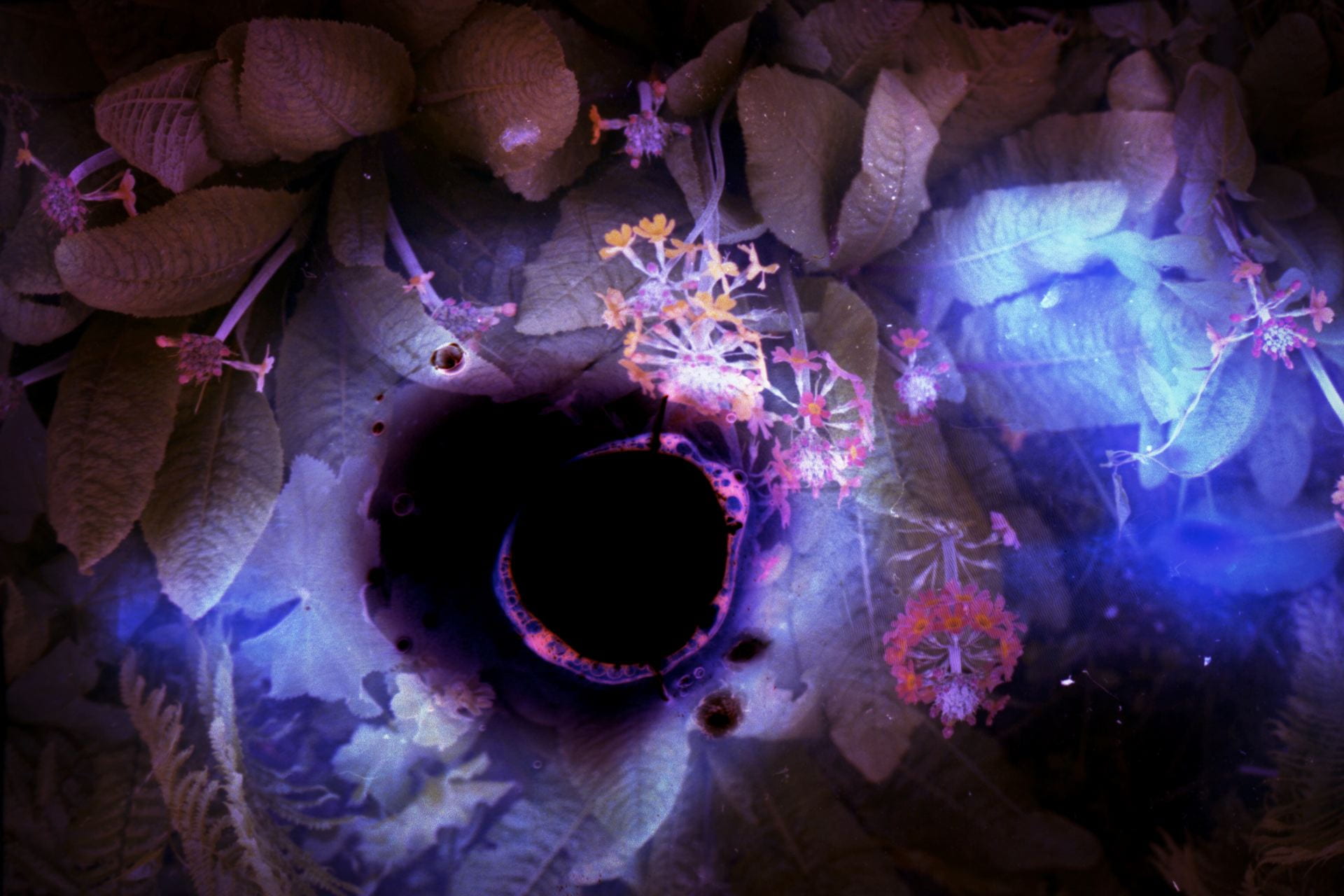

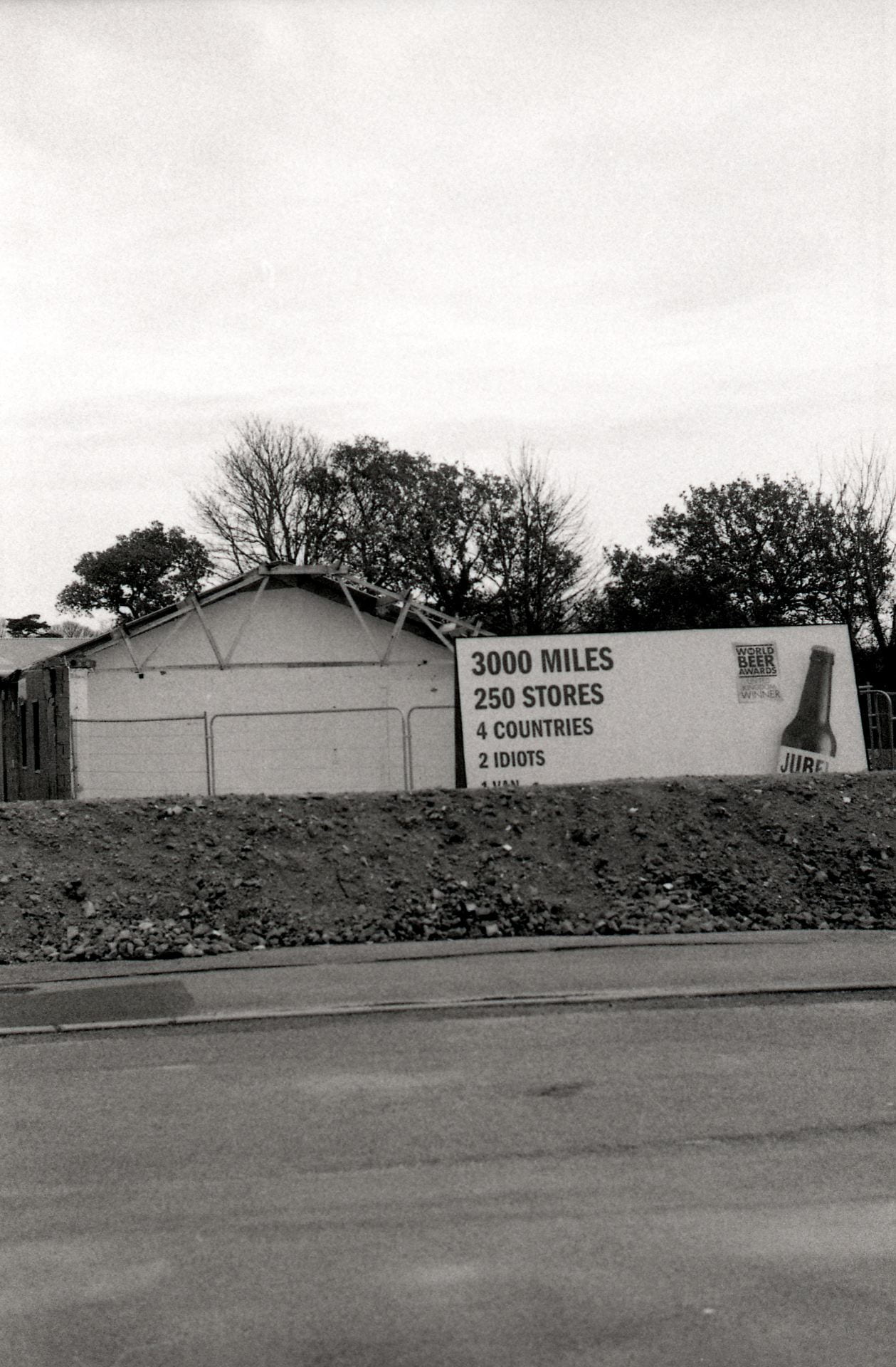

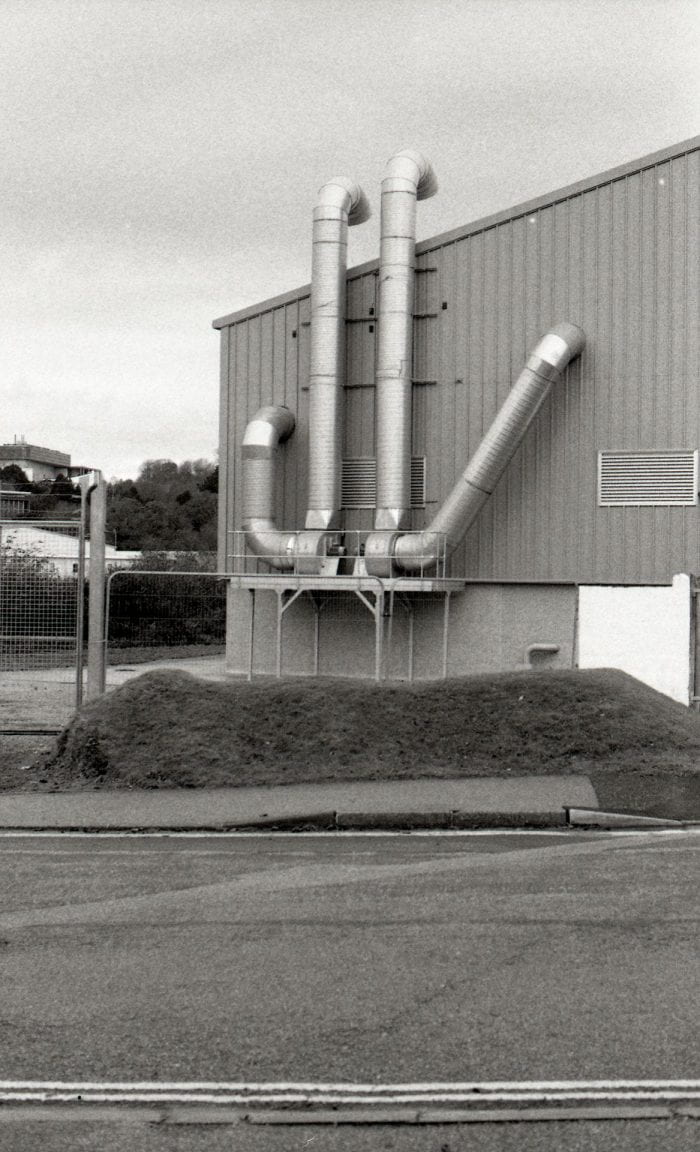

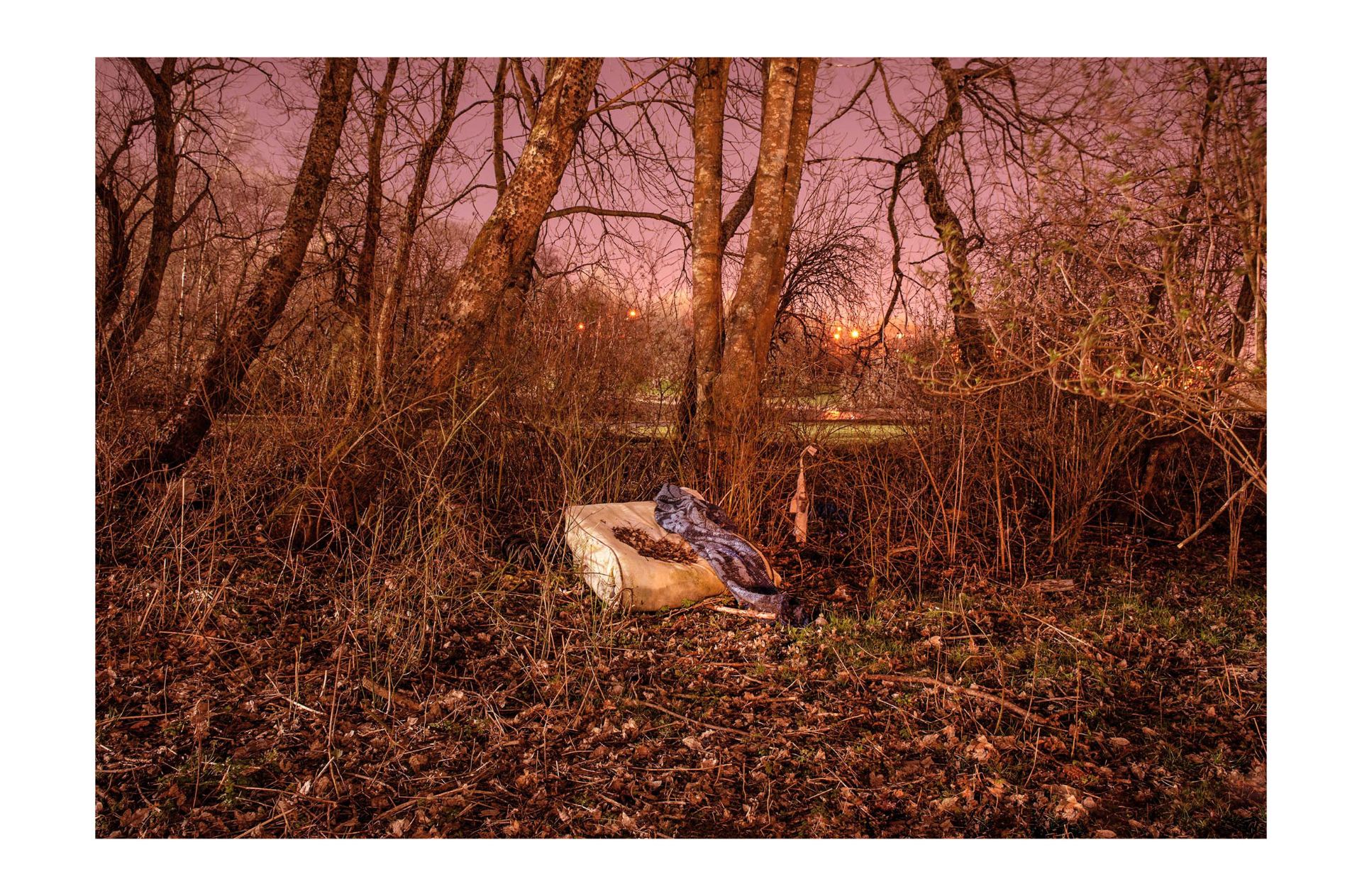

The intent for ‘The Glasgow Effect’ was to illustrate how the East End urban landscape continues to be a place of desolation; neglected, and overlooked, resulting in issues being often forgotten or dismissed. Susan Sontag (1977) argues that, “Photographs cannot create a moral position, but they can reinforce one-and can help build a nascent one.” (Sontag 2007:19). Throughout this process I explored the concepts of New Topographics, place/non-place and liminal space (day and night photography) by constructing a surreal environment from the reality of the situation. The rationale behind this being to demonstrate how sections of these locations continue to be placed in a state of limbo, unable to evolve.

The aim was to raise awareness on The Glasgow Effect by producing an ambiguous narrative that has an aesthetic allure which grabs the audience’s attention to review, reflect and consider what is being portrayed. Mark Neville remarks, “I’ve always felt that because photography deals with reality, I’ve got an ethical responsibility to try and change the world” (Neville cited in Warner 2020). I made a conscious decision to continually consider how best to represent the community that has less opportunities than other sections of society.

Todd Hido comments, “As a photographer, I want to tell you just enough with the pictures to activate your desire to know more.” (Hido 2014:28). With that in mind the photographs produced where formed by my subjective view as a non-native, current resident, and a photographer. The prime focus was to enable the audience to form their own interpretation as “part of Barthes strategy is to erase authority figures and to replace a single voice with multiplicity” (Seymour 2017:41), and with a collective consensus it would spark discussions on the topic.

When it came to the ethics, authenticity, and representation of the East End I embraced the fact I am a resident and a non-native which allowed me to regard the community from various perspectives. In the beginning, I felt the daytime photographs objectified the landscape in a harsh and literal way. I observed the subject matter covered was somewhat autobiographical, with Covid-19 halting the possibility of collaborations, it became my responsibility to interpret this respectfully. Similarly, George Shaw’s paintings presented familiar British housing estates commenting that, “It has been said my work is sentimental. I don’t know why sentimentality has to be a negative quality. What I look for in art are the qualities I admire or don’t admire in human beings” which is what I am looking for (Shaw cited in Artnet n.d.). Like Shaw, Peter Mullan directed, wrote, and starred in ‘Neds’ (2011), that incorporated his experience of 1970’s working-class Glasgow’s gang culture. In an interview Mullan spoke of younger generations repeating the cycle due to the environmental conditions (Mullan cited in The Guardian 2011).

Being surrounded by ‘The Glasgow Effect’ daily it made sense to incorporate my take on the issue to illustrate the cast away sections of society. Sontag discussed, “Someone who is perennially surprised that depravity exists, who continues to feel disillusioned (even incredulous) when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood.” (Sontag 2004:71). With that in mind as an outsider I am perplexed why little has changed with the community disregarding the decay.

The Barbican, London, Strange and Familiar: Britain (2016) exhibition exemplifies daily living by international photographers tackling social, cultural and political life since the 1930’s, which connects to my work (BBC News 2016). Even French Photographer, Raymond Depardon demonstrated life in 1980’s Glasgow, stating that, “A Glasgow photographer would not take these photographs because it would be their everyday world.”, combining this with the human choices I made as an outsider has exemplified the reality (Depardon cited in Brocklehurst 2020). Studies have shown Britain’s obsession with class dates back to the 19th Century. The ‘Social Class in the 21st Century’ notes, “Longstanding problems such as poverty appear to be getting worse even though we live in more affluent times” (Savage 2015:3). Personally, observing these ethical concerns allows the audience to regard why this still occurs.

Traditional landscape photography is traditionally associated with a controlling gaze. Terri Loewenthal a contemporary practitioner, never uses her gender to make a feminist point but indicates, “I’m not sure that a male photographer would approach landscape the same way I do.” (Loewenthal cited in Palumbo 2019). Originating from Edinburgh, now a resident of Glasgow and a lesbian of mixed heritage I strongly believe has contributed to constructing a considered image.

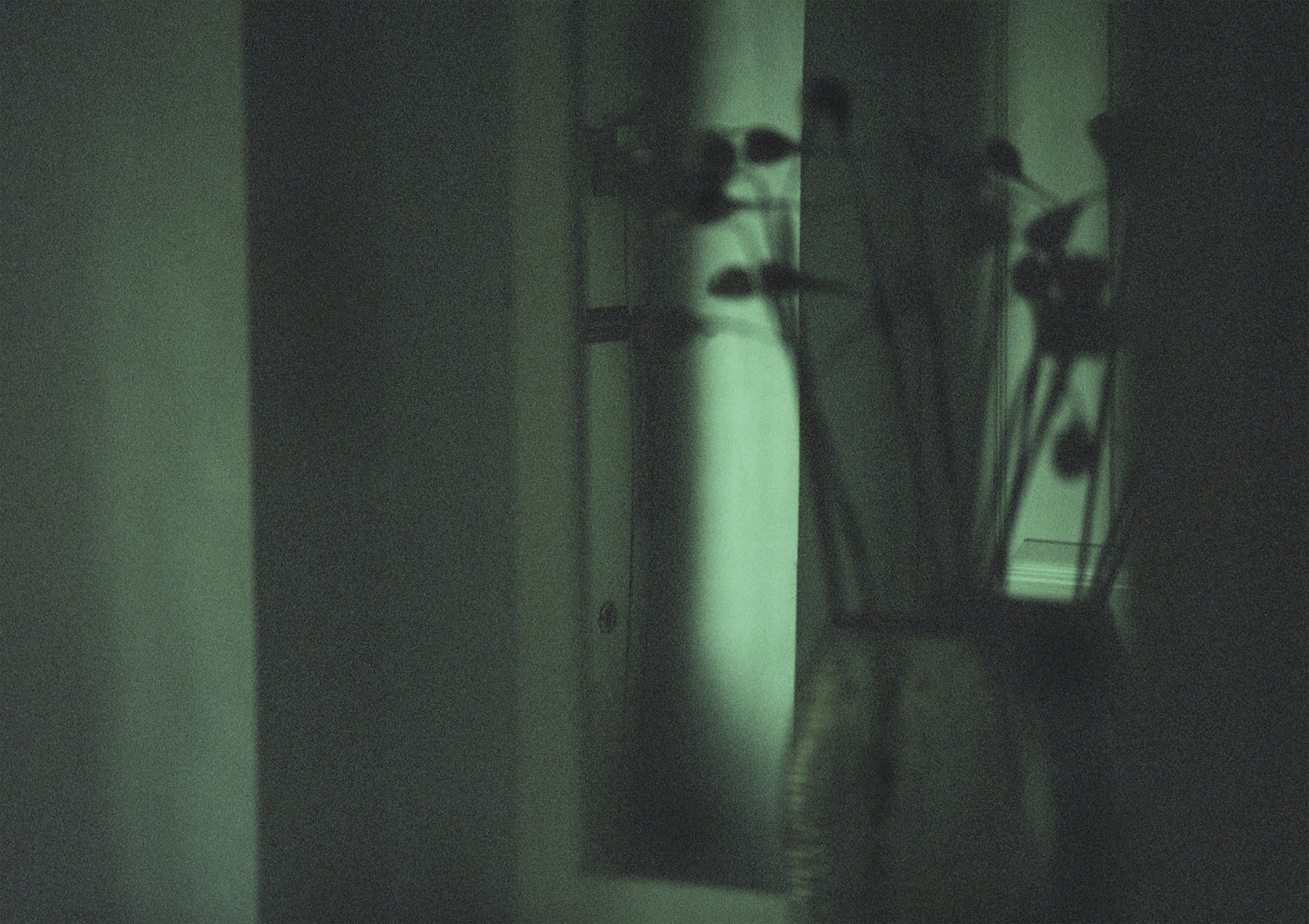

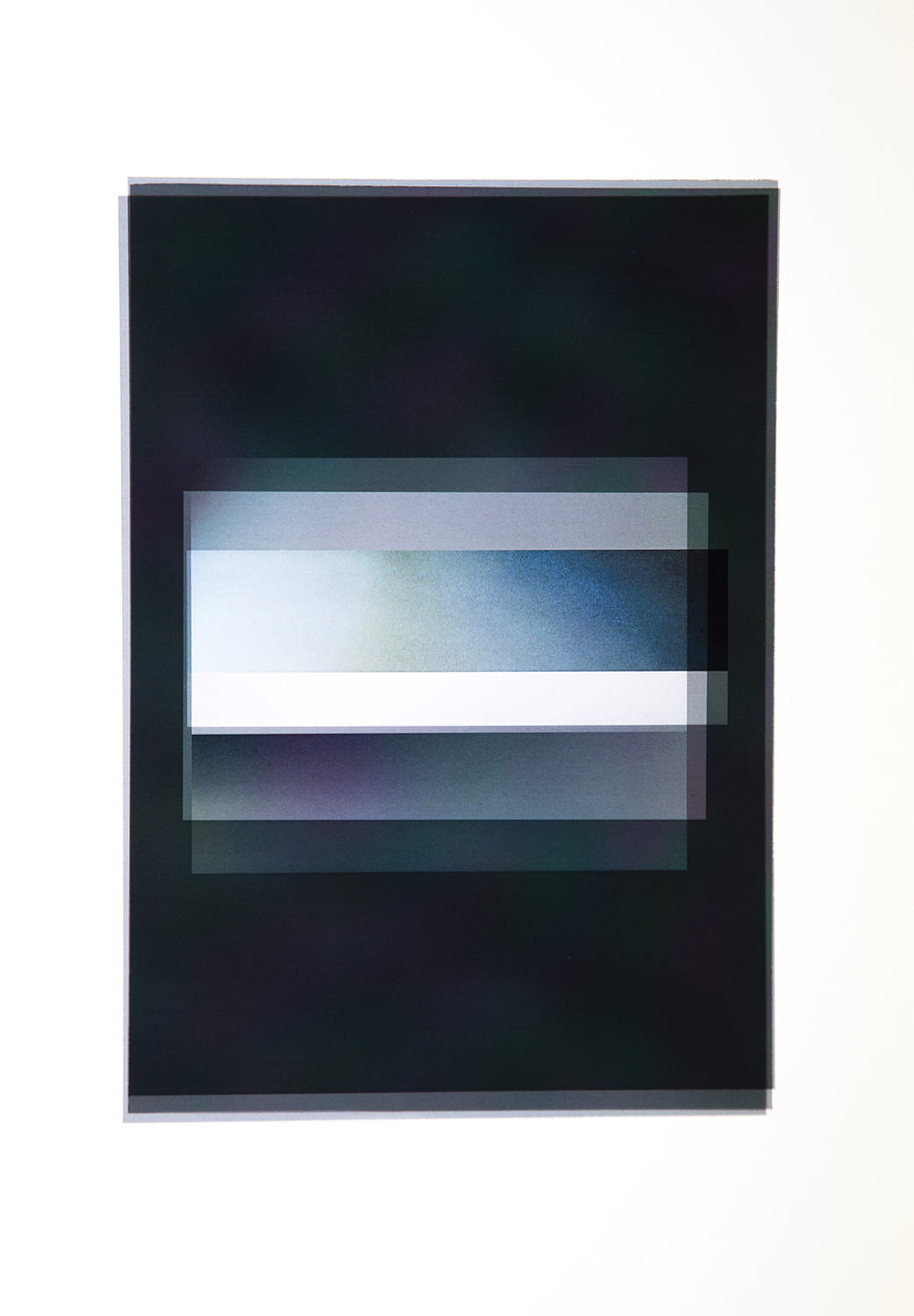

Photographer Anthony Luvera who is gay, collaborated with the LGBTQ+ community in Queer in Brighton (2014). Luvera remarks, “In this sense I feel more inside the work, but in many respects my interest in the problems of representation and the sense of representational responsibility is the same.” (Luvera 2014). This thoughtful ‘gaze’ is about breaking away from stereotypes. Yes, I depicted the decay, however the night images combine the warmth from the tungsten lighting in comparison to the coolness of day ensured the community was given the courtesy they deserve. John Szarkowski’s five photographic characteristics specifically ‘The Frame’ was key to my works overall narrative. Szarkowski says, “The photographer edits the meanings and patterns of the world through an imaginary frame. This frame is the beginning of this picture’s geometry” (Szarkowski 1980:70).

My approach was similar to Stephen Shore’s ‘Uncommon Places’ (1982), using a tripod to slowly consider what goes in and out of the frame to spark intrigue. Shore comments, “To see something spectacular and recognise it as a photographic possibility is not making a very big leap. But to see something ordinary, something you’d see every day, and recognise it as a photographic possibility, that’s what I am interested in.” (Shore cited in Clay 2018). Revisiting certain locations allowed me to see more possibilities like Shore and Hido. That certainly improved my examination of spatial awareness when appraising potential compositions. Whilst certain images did not make the final edit, trying new variations allowed for a range of images that incorporated the colour, atmosphere, and detail, as the perspectives aesthetically demonstrates neglect. Experimentation was carried out on the aesthetic value of the day and night. Within the imagery produced it was evident both portrayed the message of the community’s alienation. Photographers like Alec Soth, Robert Adams and Todd Hido portray everyday banality, yet regardless of the time, they tell stories that allow the audience to negotiate their own reading like my project.

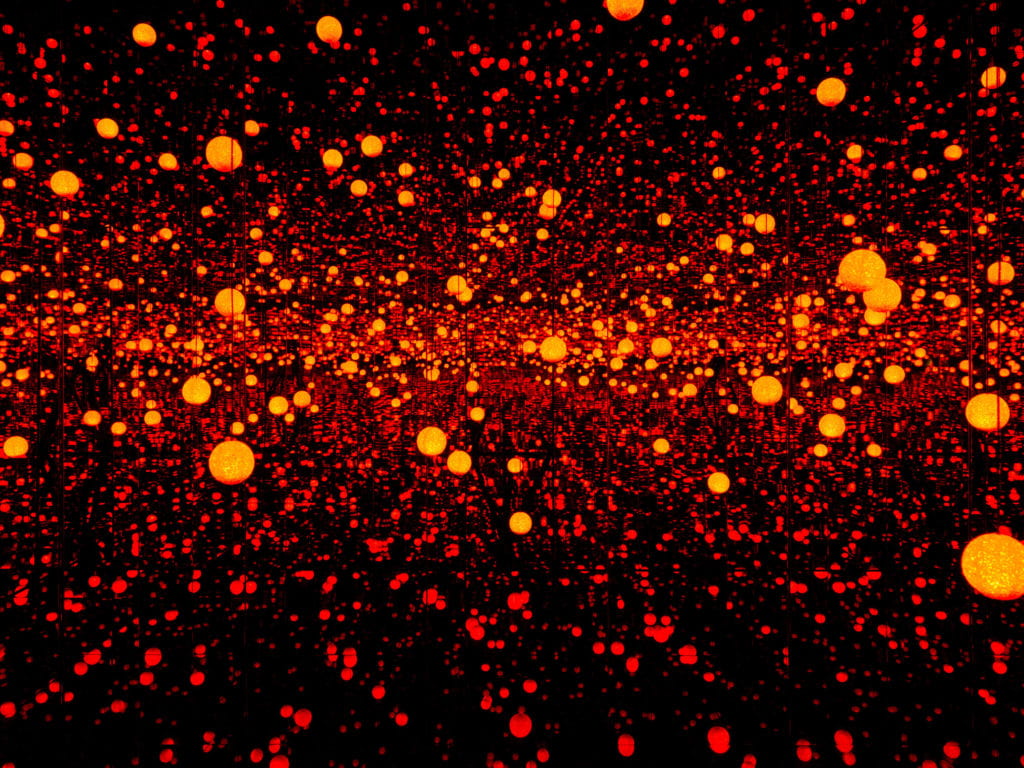

The day illustrated the same themes as night; still the night offers an unfamiliar sight, that becomes a less literal interpretation of the desolation. It has a form of beautification due to the exposure of the orange street lights and post-production. It produces an atmospheric scene of fact and fiction as Richard Misrach’s said, “it engages people when they might otherwise look away” which is vital to awaken the audience as a method of inciting change (Misrach cited in Brogden 2019:98). A continual review was carried out to evaluate if I was ethically representing the community which was personally challenging. Exploring liminal space like Soth’s, ‘Hypnagogia’ (2016), examined the process of people in a sleep limbo that created a “dreamlike experience” by altering reality (Art Rabbit 2016). When incorporating elements e.g., street lighting it produced a phantasmagoric landscape, yet posed technical issues with overexposure. Further research and experimentations surrounding in camera adjustments, shutter release timings, and post-production resulted in a vast improvement. Boosting the saturation of the orange lights in post-production resulted in an uncomfortable quality to help the audience to understand that scenes like these should not occur.

The ambience of the day and night photography is noticeably different. From the trial phase, the day appears to have a hard take on the community with cooler tones that potentially could anaesthetise the audience. The night produces a strangeness which conveyed a subtilty to outline division between them and more affluent areas. The extensive depth of field and distant perspective allows onlookers to examine more of the environment to illustrate as Jesse Alexander mentions in Perspectives on Place, that the dark can “transform” a location, in my case to create an eerie atmosphere (Alexander 2015:104). Highlighting the landscape in this way shows the viewer my sensitive approach of the run-down vicinity that the day simply cannot achieve.

Initially I set out to photograph the East End by day to depict the unwanted and neglected locations in a New Topographic style. Little did I know that the expedition into liminal space would start my exploration of night. The night’s allure enabled the everyday reality to become surrealistic, strengthening the depiction of the bleakness. Struggling with the authenticity and ethical representation was a concern, however it became evident that certain bodies of work can be subjective. Keeping a similar distance when photographing helped the work to remain a Social Documentary project rather than being an emotional singular view. Representation of this kind is how the stereotypical views associated with the community will change.

Follow Sofia Conti on Instagram

Routledge Award Winner: Winter 2022

References

- ALEXANDER, J.A.P. 2015. Perspectives on Place: Theory and Practice in Landscape Photography. New York: Bloomsbury, p.104.

- Art Rabbit. 2016. ‘Exhibition Alec Soth, Hypnagogia’. Art Rabbit [online]. Available at: https://www.artrabbit.com/events/alec-soth-hypnagogia [accessed 15 March 2021].

Artnet. n.d. ‘George Shaw’. Artnet [online]. Available at: http://www.artnet.com/artists/george-shaw-2/ [accessed 15 April 2021]. - BBC News. 2016. ‘Strange but familiar Britain seen by foreign photographers. BBC News 16 March [online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/in-pictures-35801837 [accessed 08 February 2021].

- BROCKLEHURST, Steven. 2020. ‘How a Frenchman captured the ‘exotic’ Glasgow in 1980’. BBC News 8 November [online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-54800689 [accessed 08 February 2021].

- BROGDEN, Jim. 2019. Photography and the Non-Place, The Cultural Erasure of the City. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, p.98.

- CLAY, Edward. 2018. ‘Book Review, Stephen Shore: Uncommon Places’. The Independent Photographer 12 December [online]. Available at: https://independent-photo.com/news/stephen-shore-uncommon-places/ [accessed 01 March 2021].

- HIDO, Todd. 2014. On Landscapes, Interiors and the Nude. New York: Aperture, pp.28 & 119.

- LUVERA, Anthony. 2014. Interviewed by Patrick Fox in Photoworks [online]. Available at: http://www.luvera.com/dialogues-and-perspectives-collaboration-in-focus-anthony-luvera-in-conversation-with-patrick-fox/ [accessed 03 March 2021].

- MULLAN, Peter. 2011. Interviewed by Andrew Pulver and Henry Barnes in The Guardian [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/video/2011/jan/19/peter-mullan-neds-interview-real [accessed 18 April 2021].

- MULLAN, Peter. 2011. Neds [Film].

- PALUMBO, Jacqui. 2019. ‘Did Ansel Adams’s Male Gaze Influence His Landscape Photography?’. Artsy 13 August [online]. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-ansel-adamss-male-gaze-influence-landscape-photography [accessed 24 February 2021].

- SAVAGE, Mike. 2015. Social Class in the 21st Century. London: Pelican, p.3.

- SEYMOUR, Laura. 2017. An analysis of Roland Barthes’s The Death of the Author. London: Macat Library, p.41.

- SONTAG, Susan. 2004. Regarding the Pain of Others. London: Penguin, p.71. Available through Falmouth University Library.

- SONTAG, Susan. 2008. On Photography. London: Penguin, p.19.

- SZARKOWSKI, John. 1980. The Photographer’s Eye. New York: MoMA, p.70.

- WARNER, Marigold. 2020. ‘Mark Neville reflects on his practice and the importance of giving back’. 1854 Photography 26 February [online]. Available at: https://www.1854.photography/2020/02/mark-neville-deutsche-borse-parade/ [accessed 23 December 2020].