Or, Interesting Visions?

By Kieran Bennnet (23rd August 2021)

‘Ordinary, everyday objects can be made extraordinary by being photographed. Because we may ordinarily pass these objects by, or keep them at the periphery of our vision, we may not automatically give them credence as visual subjects within art’s lexicon’ (Cotton, 2018, pg.115)

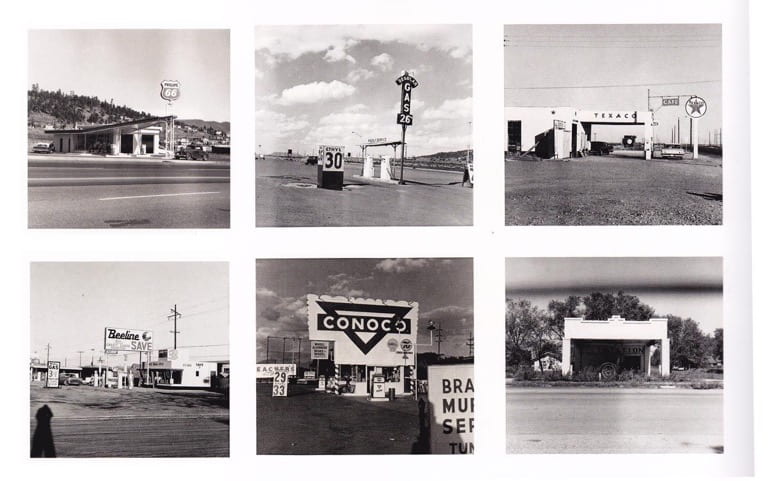

The bad is becoming the good, the elite is becoming the generic and the boring is the interesting. The photography world is extending the idea of “art” into the lesser observed or overlooked. Neville Wakefield stated, “Bad photography now reigns […] it makes for good art at times when good photography witnesses only the flow of technical virtuosity into addictive banality” (Wakefield, 1998. pg.238-247). The common place, the banal, the amateur and the boring is becoming fascinating though a post-modern scope. This essay explores what constitutes boring in the photographic world

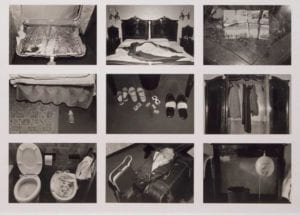

Stephen Bull stated “[The] image‐world fragments ordinary life: it encourages vicarious experience, stimulates material desire and determines the demands placed upon reality” (Bull, 2020. Pg.351). In terms of vernacular photography, Shafran an artist (Figure 1), captures a pile of receipts in the domestic space, boring right? However, the receipts draw you into questioning why they are piled, why they are needed and why so many? The most mundane becomes a mystery, the reality that nothing “boring” is there. Our own minds attribute boredom to the subject when we perceive it as dull. Shinkle defined this form of boredom as a “temporal concern; a forced inactivity of mind; a temporary slowdown of the normal flow of perception” (Shinkle, 2004. Pg.168). The mind makes you bored, but in fact there is nothing that could be said to be universally boring, boredom is a subjective response to a stimulus or lack thereof.

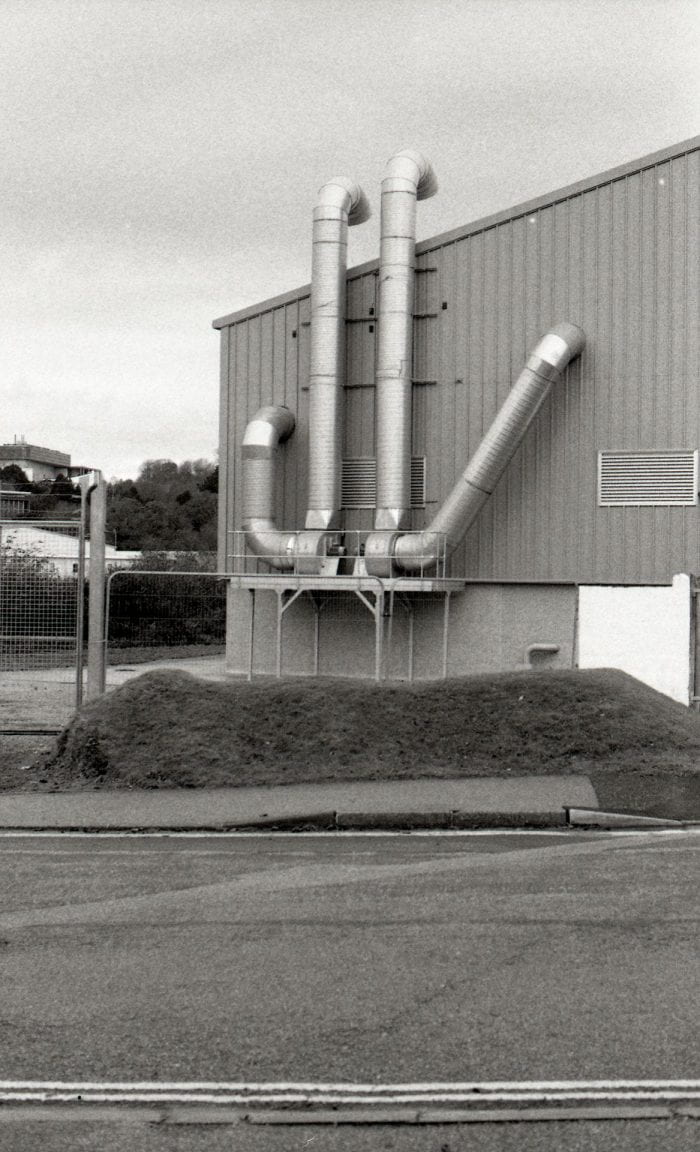

To be bored is a natural emotion, but it depends on individuals, what constitutes boring. Some suggests boredom has positive aspects, “boredom motivates pursuit of new goals when the previous goal is no longer beneficial” (Bench & Heather. 2013). Others emphasize how boredom is a space between interests, anybody can experience, it is just subjective to what extent boredom is experienced. Walter Benjamin had suggested “boredom helps to develop a critical aware-ness of those activities which are ordinarily too banal or repetitive to merit attention” (Benjamin. 2002. Pg.216). Shore (Figure 2), has used a milk carton to highlight the beauty of the domestic and usually quite dull space. This endless red void and the carton which appears to be floating but in fact is just sitting on the table, this piece of rubbish becomes acknowledged, intriguing to view.

Within the photographic world, a photograph can highlight what is normally unseen or ignored, it becomes noticed and therefore is no longer boring. Sontag suggested “Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality as a recalcitrant, inaccessible; of making it stand still. Or they enlarge a reality that is felt to be shrunk, hollowed out, perishable, remote” (Sontag. 1979. Pg.120). A photograph makes a dull moment seem more worthy of attention. When one accepts that boredom is the place between ideas, you readily agree that something of interest is out there but is yet ignored or undiscovered.

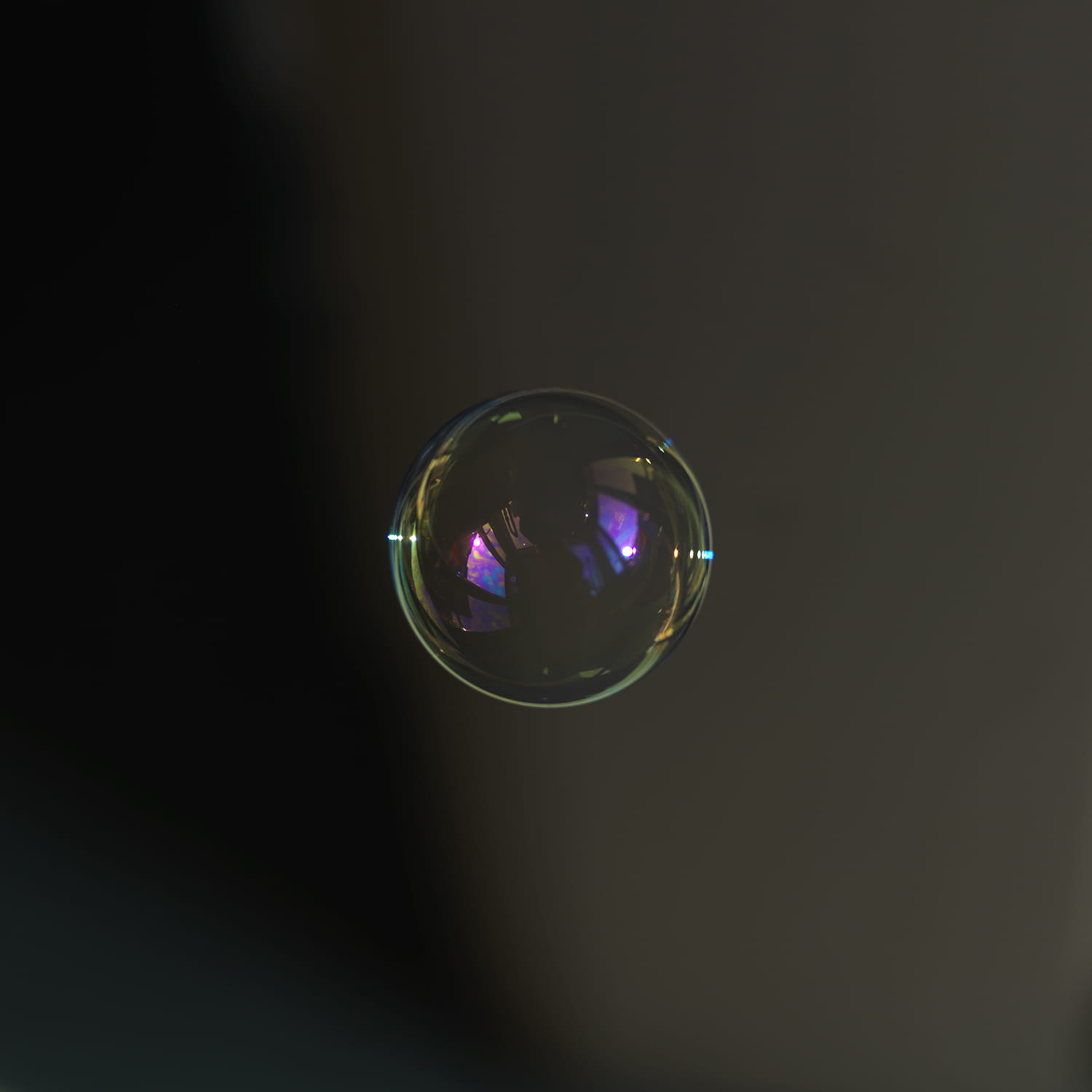

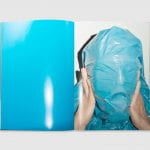

The scene (Figure 3) from American Beauty pushes this idea of the unseen delicacy, turning our gaze from something boring, into something beautiful. In this scene Ricky (Wes Bentley), is showing a video that he recorded to Jane (Thora Birch) saying “Do you want to see the most beautiful thing I ever filmed? […] this bag was just… dancing with me … like a little kid begging me to play with it.” (Bentley, Wes. 1999). The character reveals this beautiful side to life, through a bag. Thereby proving “boring” or something to be defined as that, is a social construct. There is always more to discover in the mundane and the lens brings into focus how beautiful the everyday truly is, opening our eyes to the world’s hidden treasures.

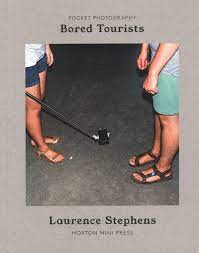

Case Study: Laurence Stephens Bored Tourists (2018)

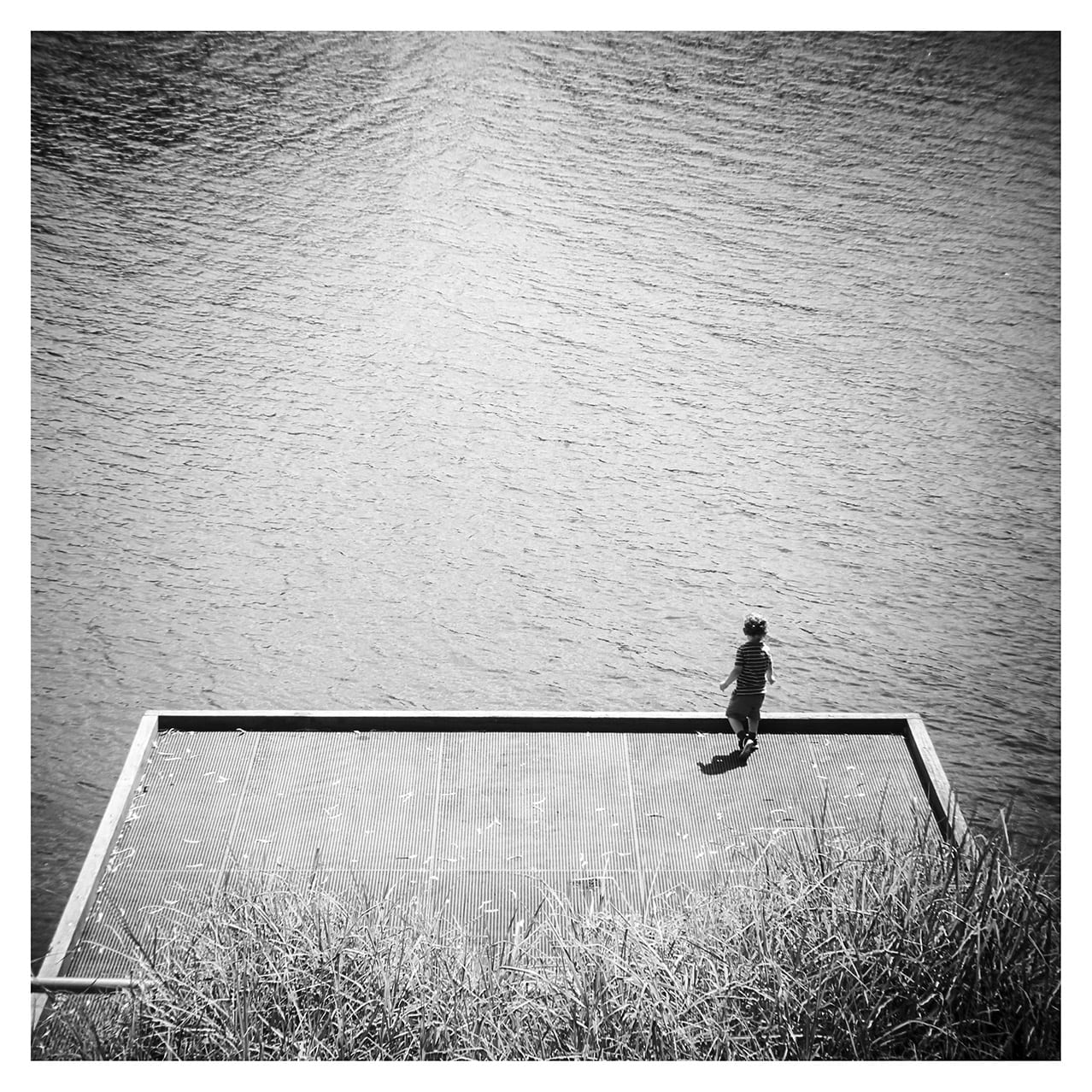

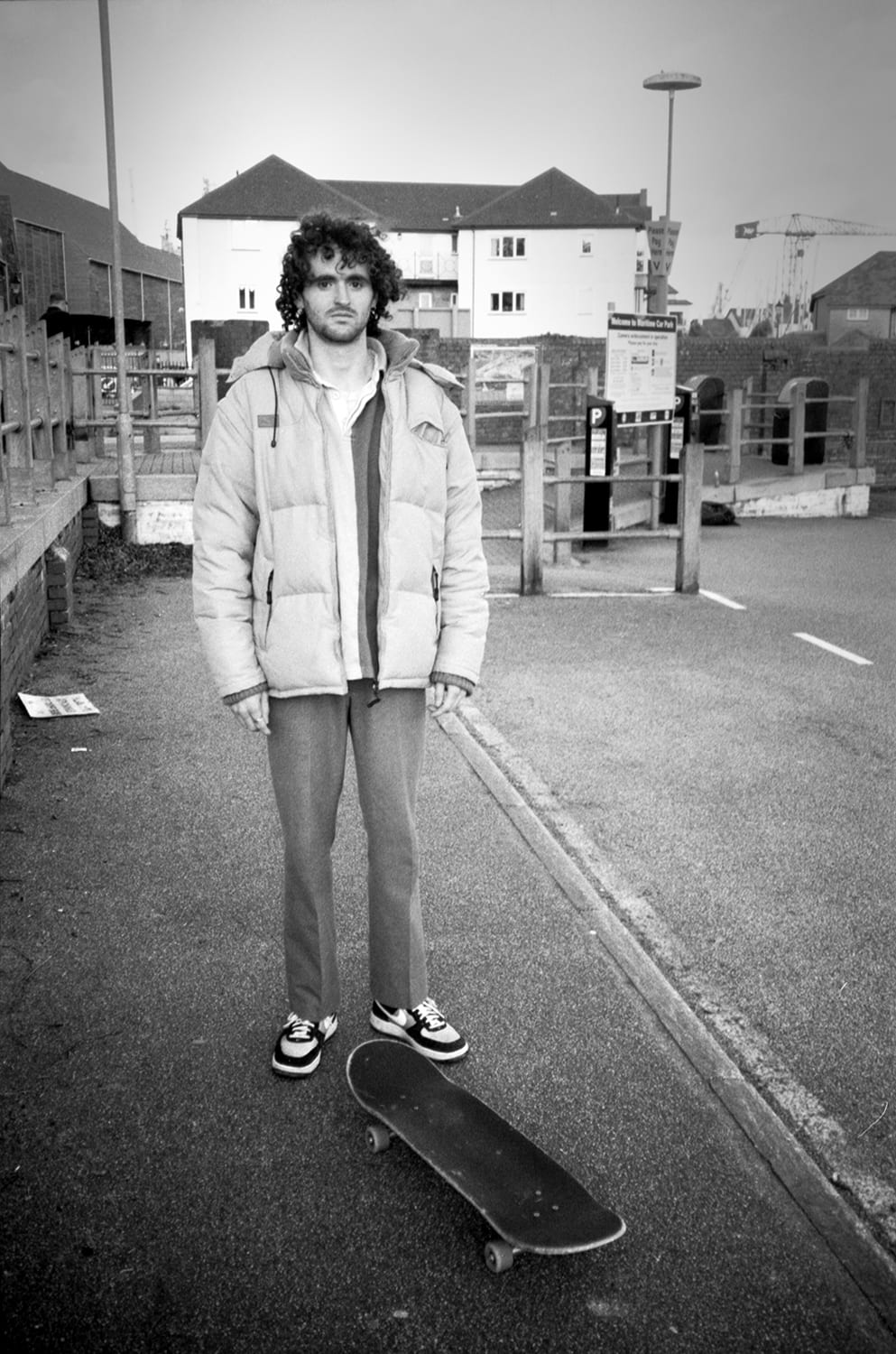

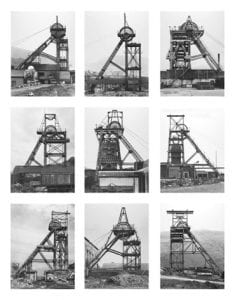

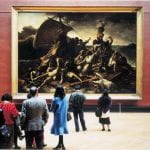

The traveller can be a prime example of boredom, their journey to a destination to find something more interesting than their mundane day to day life. Laurence Stephens’ Bored Tourists explores the complexities of boredom and the mundanity of tourism Referring to Figure 4, he stated that “Juxtaposed against the beautiful architecture was an array of bemused, disillusioned tourists, bored, half-asleep, unintentionally waiting to be photographed,” (Stephens, 2018). He projects the obvious boredom of these subjects into clear view, transforming these quite interesting and foreign locations into moments of pure mundanity.

He highlights how dependent these tourists have become on their cameras needing to document every event that has happened, rather than enjoying that moment in the real world. Richard Chalfen once noted “It has even been suggested that some tourists pay so much attention to photographing places, sites, etc. that they have to wait until they get their pictures back to see where they’ve visited.” (Chalfen. 1987. Pg.101). Stephens suggests that tourists recently (with the rise of smartphones) look at an image of the place rather than the place itself. As he stated, “Along with our need to record what we are doing while we’re travelling is the fact that with our smartphones, we have a constant stream of entertainment to draw us away from our ‘real life’ experiences.” (Stephens. cf:Hardy, 2018).

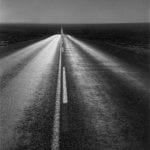

The act of ‘fulfilling a goal’, (Bench, 2013), is one aspect that I see in Stephen’s work. Take for example Figure 5, the people within the frame appear to be comedic or novel in their appearance, emphasising their position as characters placed into an unknown situation. The woman looking down the path, the man pointing a camera at what appears to be nothing and the couple looking lost in the field behind, all come together as if they are looking for something interesting to end their boredom. Stephens has shown a different perspective to tourism in its mundanity, by revealing the individuals as those escaping a mundane life to explore one of a foreign land. They search for the interesting to alleviate their boredom but are never successful to find a goal, overcoming their boredom. Stephens uses vibrant colours mixed with crowding of the frame and using a flash, clearly identify a point of focus; but despite this, there is arguably still nothing ‘interesting’ to show, besides bemused tourists. Stephens emphasises the boredom and never-ending cycle of boredom, no matter what you do or where you go.

References

- Baker, Tora. (2018). ‘Bored Tourists: a colourful, ironic look at tourists on holiday, documenting their odd behaviour’ in Creative Boom (31st July 2018). Available at: https://www.creativeboom.com/inspiration/bored-tourists-a-colourful-ironic-look-at-tourists-on-holiday-documenting-their-funny-behaviour/ [Accessed 5 February 2021].

- Benjamin, Walter. (2002) The Arcades Project USA: Harvard University

- Bryant, Eric & Neville, Wakefield. (1998) Veronica’s Revenge: Contemporary Perspectives on Photography New York: LAC

- Bull, Stephen. (2020) A Companion to Photography New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell

- Cotton, Charlotte (2018) The Photograph As Contemporary Art London: Thames and Hudson

- C41 Magazine (2018) ‘The Bored Tourists of Laurence Stephens between Spain and Portugal’ in C41 Magazine (20th August 2018) Available at: https://www.c41magazine.com/laurence-stephens-bored-tourists. [Accessed 12 February 2021]

- Dixon, Richard (2011) ‘Paul Theroux’s Art of Travel’ in The Guardian (4th June 2011) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2011/jun/04/paul-theroux-questions [Accessed 6 February 2021].

- Mendes, S., Bentley, W. & Birch, T. (1999). American Beauty [Film]

- Shinkle, Eugénie. (2004). ‘Boredom, Repetition, Inertia: Contemporary Photography and the Aesthetics of the Banal’ in Mosaic Vol.37, No 4.

- Sontag, Susan. (1979) On Photography London: Penguin

- Theroux, Paul. (2008). Ghost Train to the Eastern Star Boston: Houghton Mifflin