Lucas Gabellini-fava

‘My practice is quite hard to pinpoint. However, recently I have been making work where I explore new technologies and image-making techniques’ Lucas Gabellini-Fava

by Louis Stopforth (9th July 2019)

LS: Firstly, could you tell the readers a little bit about your own practice as well as how you came work alongside Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin? What projects have you worked on with them?

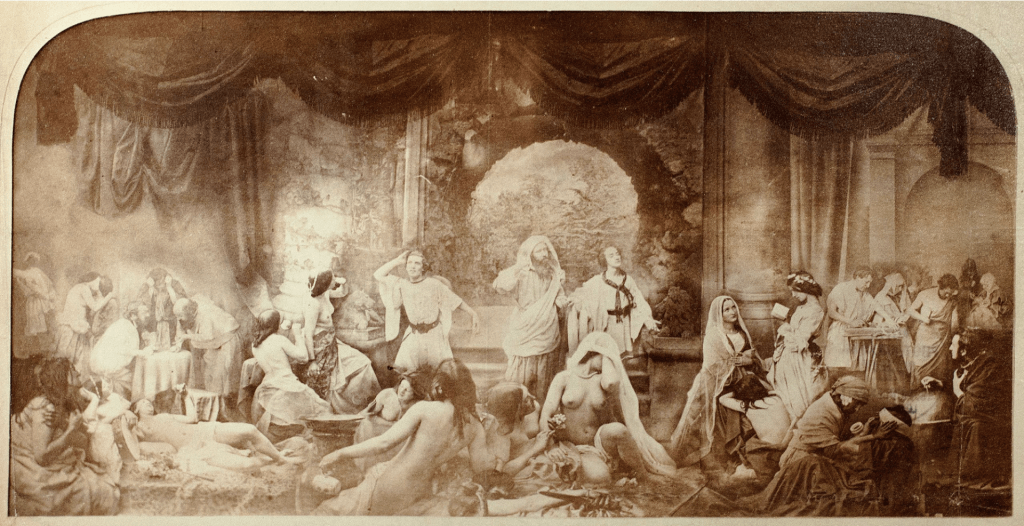

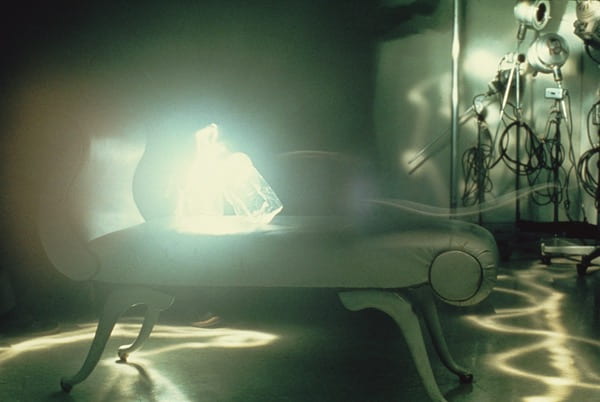

LG-F: My practice is quite hard to pinpoint. However, recently I have been making work where I explore new technologies and image-making techniques. I am currently really interested in photogrammetry and the amazing potential of 3D scanning and printing. My latest work Programmed by my Father involved a deep learning artificial intelligence that learned to create new conversations between my father and I from every conversation that we have had in person in the last year.

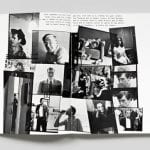

My friend was working for [Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin] at the time and had to go and shoot a project in South Korea for a while so he asked me to take over his duties in the studio for a while. He came back and we ended up both sticking around and working alongside each other. This worked really well because we were both also studying full-time. He has now left but I have stayed on, especially to help with Chopped Liver Press. I have worked on a few, but my biggest input was with their new book The Future of Images. It was a huge job and I think that we were all super happy and proud when it was over and printed.

LS: For the last three years, you have worked for Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin (Oliver in particular) in their London Studio, whilst also running and managing Chopped Liver Press. I am interested to know how these two work environments operate and how they differ.

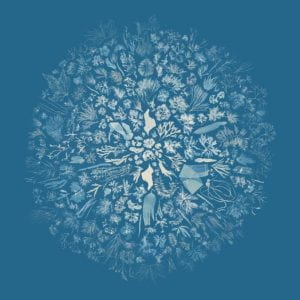

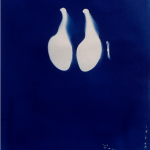

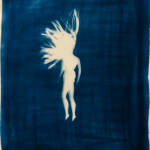

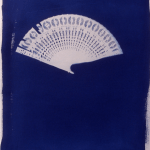

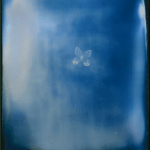

LG-F: Chopped Liver Press is an interesting one in terms of the way it works alongside Adam and Oliver’s practice. The Chopped Liver Press studio is housed in the same studio as Oliver’s in London and so we sort of share the space in half. I think that Oliver and I have got into a really good rhythm of working on these two things at once. It is also really important for Chopped Liver Press to live in that environment as the whole project lives and thrives off of what Oliver and Adam are working on at that time or what they are interested in. The prints almost become pages of a diary that mark a certain time in the studio.

LS: The work undertaken at Chopped Liver Press seems to me more therapeutic and instinctive in comparison to the work undertaken at the London space. Is this the case?

LG-F: Definitely. A lot of the time I am working on Chopped Liver Press independently (under the artistic direction of Oliver and Adam) to allow them to work on their collaborative practice, however from time to time we will brew some coffee in the morning and play around. We’ll make frames, discuss ideas and pin stuff up on the walls. Our best conversations always start over coffee and a Chopped Liver Press poster.

LS: In a recent video, Oliver remarks that creating the monthly posters from Chopped Liver Press is a ‘meditative’ process. I feel that all the projects that the duo have produced so far have this quality. The conceptualisation of their work is highly considered. How much of the physicality of the work comes from consideration and how much comes from creative instinct and experimentation?

LG-F: This is a difficult question because in terms of a duo I think that both Oliver and Adam have very different personalities and they bring very different things to the table. Ideas seem to stem from books, the news and encounters with people and then it will grow from there. There is no set formula for how the work is made honestly. The conceptualisation is most definitely always highly considered but it always stems from a lot of experimentation and honestly a huge amount of interest in a wide range of different fields. They are both constantly keeping up to date with new technologies, the news and what other artists are doing.

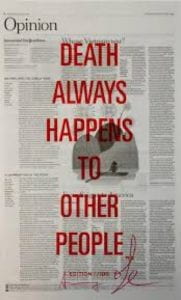

LS: The Joseph Beuys quote ‘Bandage The Knife And Not The Wound’ appears both within the context of posters produced by Chopped Liver Press as well as a project of the same name. How often do the two separate outlets inform the other?

LG-F: They almost always inform each other in one way or another. Chopped Liver Press is a direct response to everything that happens in the studio and the work that they are making or conceptualising in the month that the poster is released. In a way it is an amalgam of all the most important ideas and quotes that have inspired work that has been made in the Broomberg and Chanarin studios.

LS: Talking of Joseph Beuys, his work was both a spiritual experience as well as a reflection of humanity and modern history. Oliver and Adam’s work share these qualities and additionally operates as an artistic experience. Has this connection to art always been a part of their practice? Even back when work was made in a more typical photojournalistic way, or has this developed when producing work for a gallery context?

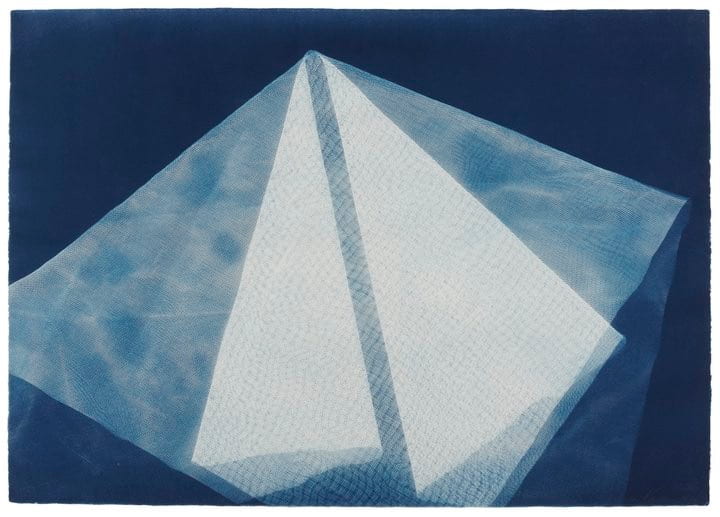

LG-F: Oliver and Adam were really at the forefront of what they do, even when they were working together at Colors Magazine. We have a poster up on the door of the studio that states “you don’t take a photography, you make it” – and this is what they have always done. Their work has never been just about the ‘photograph’. I think their work begins with the acceptance that photography is a flawed medium at its core and through this they have found beautiful ways to tame and utilise the photographic to comment on and scrutinise any issues surrounding it.

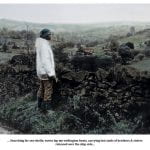

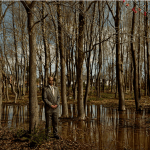

LS: Also coming from their photojournalistic background, was The Day Nobody Died work as much a deliberation on physical presence in areas of conflict as well as that of photography, censorship and the accuracy of depicting conflict?

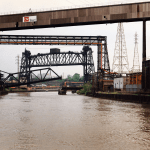

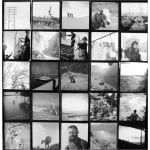

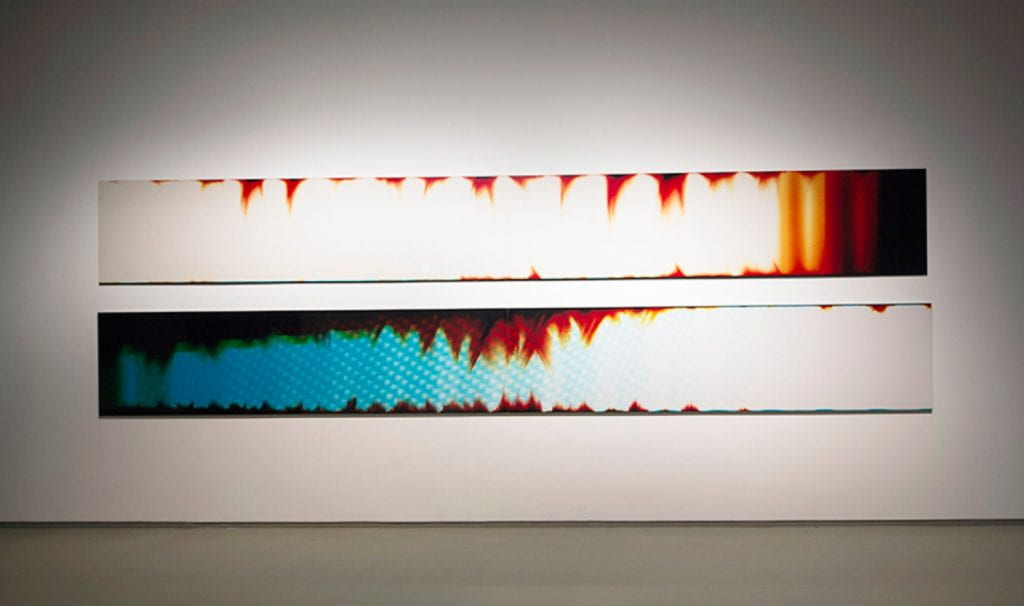

LG-F: The Day Nobody Died is one of my absolute favourite works by them. They simply unrolled a six-meter section of photographic paper in response to events that were happening around them during their visit to Afghanistan in the midst of the war in 2008. These were all events a ‘war’ or ‘documentary’ photographer would have recorded photographically, but instead Adam and Oliver created something that was simply a record of the day-to-day during the war but in a completely non-figurative way that removed any visual insight into what was happening. This completely subverted and turned the idea of ‘conflict’ or ‘war’ photography on its head.

LS: Typically, how do Adam and Oliver start their investigations? For example, does work start from a point driven by their own inspirations or do they feel an obligation to disclose certain issues to the public?

LG-F: FaceTime calls early in the morning, followed by emails with some of us Ccd into and then lots of research. I think people always tend to valorise important artists by trying to understand the ‘formula’ to their work, but I think that any artist that works by the books will quickly fade out of the limelight. Every project starts differently and ends differently, it can be by leaving a certain book on the table before locking up one evening or by watching a YouTube video. The work starts with the relationship that Oliver and Adam share and the way in which they communicate and their beautifully inspiring interest in the world around and its complicated systems and structures.

LS: When it comes to publishing and exhibiting work that utilises found imagery, such as War Primer, are there ever any legal difficulties encountered during this process?

LG-F: Yes, but I know that they always try and be careful. They have run into many issues over the years, especially because a lot of their practice is based on ‘appropriation’ – however they always manage deal with anything that pops up quite valiantly. They try and talk to people and explain themselves and their work, whilst also standing their ground and defending the work that they are making.

LS: Their work consistently questions the photographic medium, its history and its place within society.Is it because of this debate that the work produced – whether this be using found imagery or their own photographic images – can be regarded equally?

LG-F: Yes absolutely, Adam and Oliver work within the ‘photographic’, but I personally wouldn’t necessarily regard them as ‘photographers’. They use the medium as a way of turning a mirror on itself and this functions whether they are the authors of the work or not.

LS: The nature of photography tells both truth and fiction simultaneously; disclosure to a subject is given a moment at a time, but the actions of both the photographer and the context of its presentation can greatly alter its meaning. Adam and Oliver are greatly aware of this and produce work that is both a personal take on a subject as well as an informative one, reflecting the paradoxical nature of photography. How important is the conclusion of truth in engaging the viewer?

LG-F: (I understand your question here but I’m not too sure how to answer it. We can chat about it a bit if you want, if you send me an example of what you mean. Adam and Olly try and tell the truth through the photographic — which has a long history of skewing the truth. I’m not too sure how truthfulness might further engage a viewer?)

LS: The variation in aesthetic between projects is at times quite extreme and yet each project carries such importance. Is the change in project presentation always what works best for the context or is there a desired evolution of the artists practice? What can we expect to see from projects in the future?

LG-F: You can expect some amazing stuff. We all seem to be fascinated by new technologies at the moment and we are always sending each other PDFs on artificial intelligence and we are talking a lot about space! Their practice evolves with the times and it always has. I think that is one of the reasons that their work has always and will always feel so fresh and interesting and with this the aesthetics of their work changes, but it will always keep the same foundations.