How Has the Rise of Social Media & Social Influencing Impacted on Advertising?

By Amy Miles (2nd june 2021)

In 2015, Facebook launched its first UK advertising campaign, titled Friends and spanning a range of media from TV to posters, magazines and newspapers. Among these images of bodily closeness and handwritten expression there is not one picture of anyone sitting alone at a computer or on their tablet or mobile, tapping the keypad. Yet that, in essence, is what Facebook activity is. There is an inverse relation between the time anyone has to engage in real-world activities and the time they have to spend online looking at pictures, sending messages or ‘liking’ or ‘unliking’ things (and people). Facebook’s campaign draws on the world of robust physical relationships as a means to advertise its online world, which is represented in the ads simply by the box with the tick and ‘Friends’ on it. (Williamson, 2015)

Introduction

The topic of this Literature Review explores how visual material is used within advertising, and how advertising techniques have changed due to the rise in social media. In a society where social media is expanding, it’s important to understand what effects imagery on social media has on purchase decisions from the public.

The Visual Advert

When thinking about the role of visual material / photography within the advertising industry, we may think of large creative teams executing refined advertising imagery. As Swift (2015) proposes, ‘creative teams became the industry norm in advertising agencies’, with advertising shoots being led by art directors and photographers being seen as ‘cultural heroes’ for making imagery to sell items. (Swift, 2015) As a result of these teams, advertising is an expensive outgoing for companies. In 2004, Baz Luhrmann directed a 3-minute film for Chanel, which cost $42 million (Jhully, 2017).

However, in considering how such visuals are used, staging is one technique used to grab attention of the viewers (Messaris, 1996). Messaris outlines how staging of photographs is a technique used within imagery, involving manipulation of photos, as well as misleading text. In his (1996) text Visual Persuasion: The Role of Imagery In Advertising, he discusses a 1990 Volvo commercial (Figure 1) of a monster truck running over a line of cars, until getting to a Volvo which remained untouched. However, the Volvo in the advert had actually been reinforced by steel beams and that the supports of the other cars had been weakened, therefore misleading the viewer.

Despite being written in 1996, thinking about this technique, the analysis still does apply to advertising today. This is also discussed by James Fox (2020) in his documentary Age of the Image. Fox explains how advertising creates a ‘fantasy world, in which we are happier, healthier and more successful.’ (Fox, 2020) Advertisers then suggest that to make this ‘fantasy’ come true, we should go out and buy the products that they’re promoting. This applies to what Messaris (1996) was discussing in the Volvo advertisement, because Volvo created a fake reality, one which still occurs in advertising nowadays, what makes advertising successful is the fact that it relates to the everyday within consumers lives. Berger (2001) discusses how Fenske, an American copywriter, considers that ‘advertising deals with the minutiae of everyday life’ and an advert may be ‘about something that happened to you that very day’. (Berger, 2001:10). This mirrors Fox’s idea of ‘fantasy’ worlds, potentially enhancing your everyday life to become an ideal ‘fantasy’ within the everyday.

Advertising as ‘Art’?

Is advertising considered as a piece of art in its own right, or is it just purely an advertisement? One argument is that advertising cannot be art because ‘it is conceived for commercial purposes, and controlled and financed by corporations’ (Berger, 2001:13). Berger goes on to discuss how advertising professionals think that it is risky to consider creators as ‘artists’ lest the aim of the advert is forgotten. (Berger, 2001) Nonetheless, there is the idea that this depends on the extent creative freedom the creator of the advert is allowed (Bonello, 2005). (Figure 2 & Figure 3)

Bonello (2005) discusses how Peter Saville (Figure 4) has created record covers, but also advertising campaigns, maintaining creative freedom when creating the work. However, he also argues that the line between art and advertising, depends on the intentions behind the work, and whether something is simply being shown, or whether the work is trying to seduce the viewer (Bonello, 2005). Yet, Jordan Seiler proposes that ‘Ultimately the interest of advertising is not to create something that promotes thought or contemplation. It’s to promote a single message. Advertising is about monologue, and art is about dialogue. The two are completely different’ (Seiler in Krashinsky, 2010). This somewhat compliments Berger’s (2001) argument, that the creation of advertising is to send out one clear message, with ‘art’ sending out a message to the audience that requires more thought and time.

Social Media Marketing

According to Tuten (2018), ‘social media are the online means of communication, conveyance, collaboration and cultivation amongst interconnected and interdependent networks of people, communities and organizations enhanced by technological capabilities and mobility.’ (Tuten, 2018:4) Expanding on this, Zarrella (2009) discusses how social media is different from traditional media, because traditional media are ‘one way, static broadcast technologies.’ (Zarrella, 2009:1) He discusses how social media allows users to connect with one another in real time, as opposed to watching a TV commercial for example, and not being able to connect with the broadcaster instantly. With 4.38 billion global internet users, along with the fact that the ‘average user has accounts with 8 different social media services’, it’s no wonder than social media is now used to advertise products. (Tuten, 2018:5)

In terms of companies deciding which social media platform would be best for them to advertise with, Kietzmann et al (2012) conducted research focusing on the 7 building blocks that form the ‘honeycomb model’, (Figure 5) which would help companies to understand consumer engagement on social media platforms. An example of one of the blocks is ‘sharing’, relating to the ‘extent to which consumers engage, distribute and receive contents.’ (Kietzmann et al, 2012:115).

In synergy to this notion, Newberry & McLachlan (2020) discusses the importance of choosing the right type of social media campaign for the content produced, depending on who the target audience is. (Newberry & McLachlan, 2020) This idea somewhat mirrors the Kietzmann et al’s ‘honeycomb’ model, as if companies want their consumers to reproduce their content as a way of marketing, they’ll need to pick a social media platform that is easily accessible for sharing. Despite Kietzmann’s research being conducted in 2012, the ‘honeycomb model’ does still apply when thinking about what social media platform to advertise on, as numerous social media platforms now exist, even more so than in 2012. Despite more social media platforms existing, the model is still relevant and up to date with the characteristics of social media. (Figure 6).

The Rise of Social Media ‘Influencers’

According to Freberg (2010) ‘social media influencers represent a new type of independent third party endorser who shape audience attitudes through blogs, tweets, and the use of other social media.’ (Freberg 2010:90) Freberg also discusses how social media influencers are identified, explaining that this can be through the content statistics; how many times a post has been shared or how many hits on a blog there are. However, Freberg does also point out that brands cannot solely use this method to identify influencers, and that they need to use other methods to ‘evaluate the quality and relevance’ of social media influencers, as well as the influencers audience impressions. (Freberg, 2010: 91). However, Tuten (2018) describes influencers as ‘develop[ing] a network of people through their involvement in activities’, and explains that others trust and rely on influencers to give a truthful opinion. (Tuten, 2018: 94) (Figure 7)

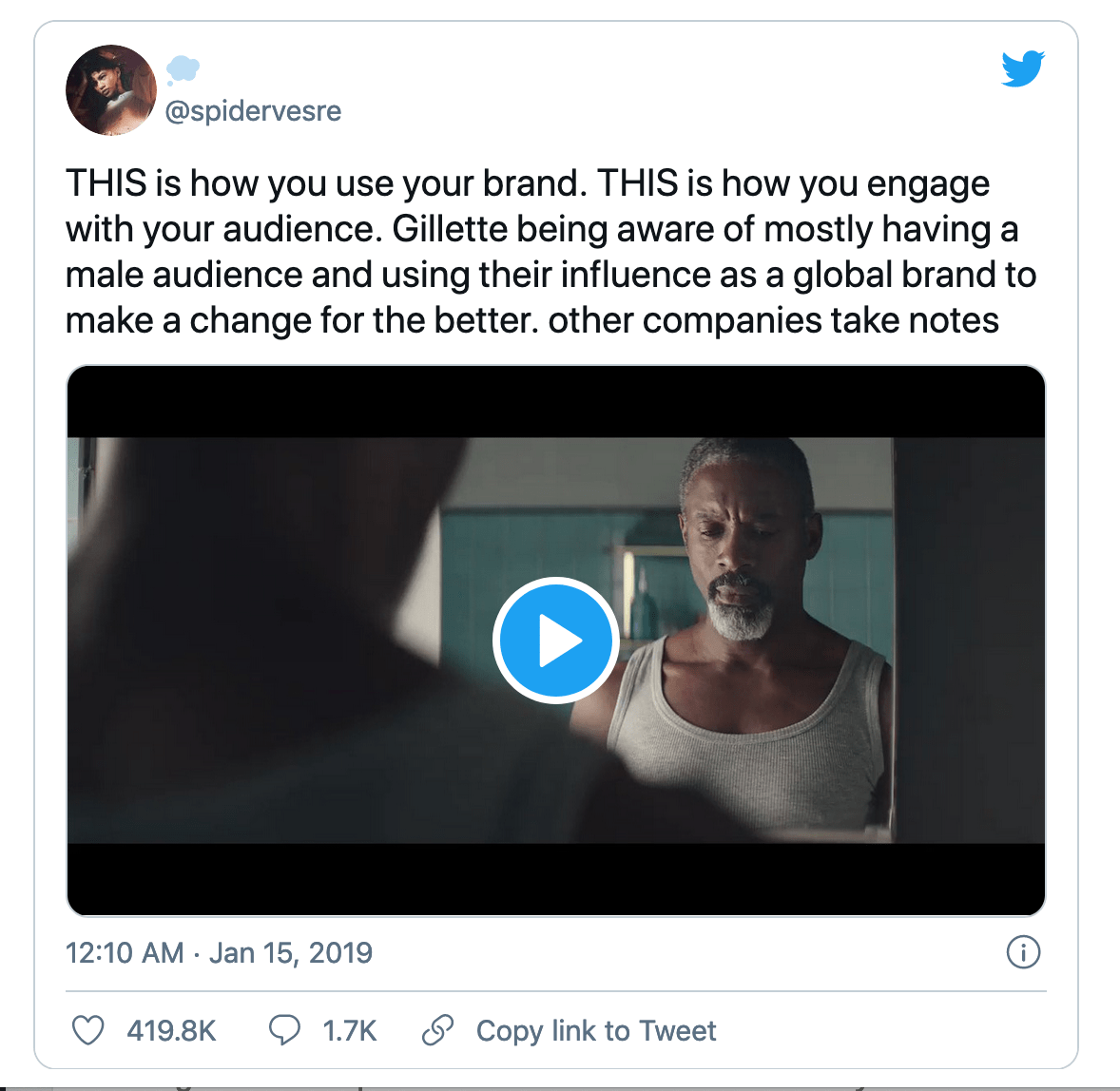

Khamis et al (2017), go on to discuss the role of celebrity endorsements (Figure 8 & Figure 9) within advertising and social media influence, explaining advertising that involves celebrities can be used within mainstream media, as well as using their own social media or websites ‘to cultivate their own audience.’ (Khamis et al, 2017: 5) However, Kl and Kim (2019) argue that the technique of using social media influencers (compared with celebrities) is more relatable to consumers, as the advertising content is being produced in the ‘context of SMI’s personal lives’ and is more ‘accessible and credible’. (Kl & Kim, 2019: 905).This links back to Fenske’s argument that advertising is at its best when it’s relatable to the everyday consumer.

Many social influencers use the platform ‘Instagram’ to showcase their personal lives, as well as advertisements for brands. According to Manovich (2015) Instagram ‘allows you to capture, edit and publish photos, view photos of your friends, discover other photos through search, interact with them…all through a single device.’ (Manovich, 2015: 11) Manovich also discusses how Instagram was used to document ordinary moments in people’s lives, that they like to show friends and family, meaning snapshot style images are the basis of Instagram posts. This leads onto Schroder’s (2013) observations regarding the snapshot aesthetic. He explores how snapshot type imagery is also used strategically for advertising. (Figure 10)

‘A key aspect of the snapshot style is an appearance of authenticity; snapshot like images often appear beyond the artificially constructed world of typical corporate communication.’ (Schroder, 2013) An emphasis on the fact that snapshot style images promote authenticity is clear within the text, and how snapshot images can show how a product can fit in with the consumers everyday life. This mirrors Kl and Kim’s (2019) arguments; namely that consumers can therefore relate to social media influencers, due to the snapshot aesthetic that their content is (often) styled around. (Figure 11)

Despite this, in Kl and Kim’s (2019) research, proposes that the ‘attractiveness’ of the Instagram photo means whether the consumer believes that the ‘social media influencers content to be visually or aesthetically appealing.’ (Kl & Kim, 2019: 909). Therefore, suggesting that if a consumer finds an influencers’ content appealing, they’re more likely to think that they have good taste, therefore are more inclined to buy the promoted product. The whole idea of social influencing through images on Instagram, links back to what Fenske stated about how adverts are successful if they relate to the everyday, which is what the snapshot type images demonstrate, as they relate to consumers even more so than high budget advertising shots. Yet, creating an appealing image, requires thought and potential editing to make it attractive, which defeats the idea of images being ‘snapshot’ like, so whether influencer ads are really in the style of the ‘snapshot’ aesthetic is debatable, due to the thought and processing that is required to make an image visually appealing. (Figure 12)

Moving on from this, Instagram has the ability to deceive consumers, as false realities are being exposed. In Driel and Dumitrica’s (2020) study on Instagram influencers, the topic of highly edited and overly curated images is explored: one example being that influencers may over-prepare images; they may include props that aren’t realistic in an everyday setting. In addition, the study looked into how influencers now ‘invest in improving the quality of their photos by migrating toward professional equipment.’ (Driel and Dumitrica, 2020: 12) With this being said, the study also went onto say how Instagram content is moving towards looking like an advertisement, rather than a regular upload to Instagram – thus removing the sense of authenticity, and that influencers are starting to make their own higher budget advertisements to make the images attractive. This may have an effect on consumer engagement, because consumers like to see relatable content, but on the other hand, relatable content might not necessarily be as attractive as higher quality content that is produced with higher quality equipment/budgets. As we’ve seen above in Kl and Kim’s (2019) text, attractiveness of an image is important when wanting consumer engagement and purchasing.

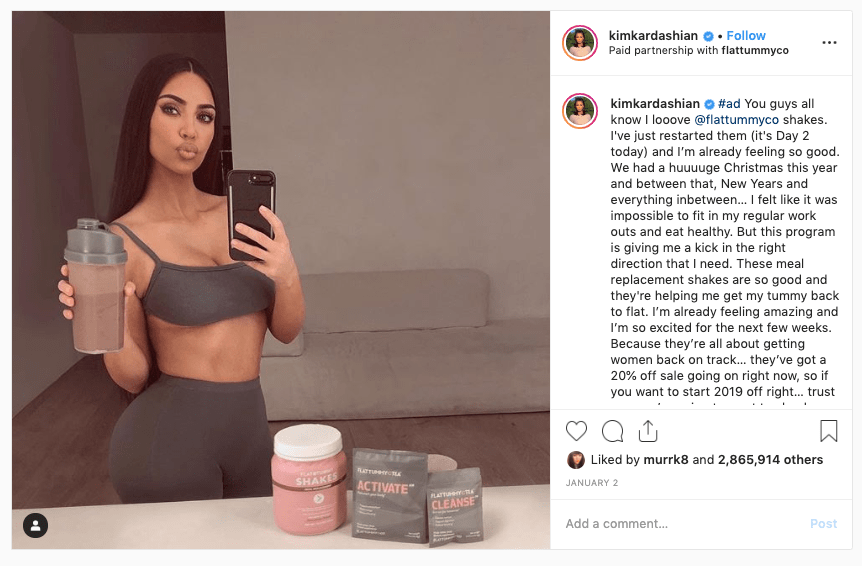

With regard to to posts being unrealistic, this may come down to how brands work with the influencers themselves. Haenlein’s (2020), study investigated how to be successful on Instagram, and discussed how brands can become too involved when working with influencers in terms of how they promote the product. It concludes that brands shouldn’t get too involved with the creative content side of the arrangement, because it may result in multiple influencers producing the same content, which consumers would not percieve as authentic. Additionally, approval of content was discussed, because brands don’t want influencers to promote false information, for example Kim Kardashian’s advert with brand ‘Flat Tummy’; (Figure 13) she promoted a product which claimed to cleanse your body and lessen bloating. This is important when producing content for an audience, as false advertisement can discourage consumers from trusting and purchasing from the brand.

Conclusion

The material explored here seems to suggest that when social influencing is carried out in a truthful and reliable manner, it can be successful for brands, however it did identify that Instagram influencing is becoming more and more commercial, due to taking steps that aren’t as relatable to consumers – moving away from the authenticity and snapshot aesthetic that influencing initially started out with. This then suggests that influencers are more advertising creators (who also create other relatable content), rather than people who create relatable content as well as a few adverts sporadically. This relates to what Berger (2001) was discussing, especially regarding being an ‘artist’; are social influencers creators, or are they simply just another form of advert for brands to use? When exploring the literature, it was significant that there was a lack of research regarding the extent to which influencer created images affect consumers / what consumers think of influencer content – in terms of thinking visually rather than statistically, with Driel and Dumitrica’s (2020) work being one of the key studies in this area.

Follow aMY MIles on Instagram

References

- BERGER, Warren (2001) Advertising Today London: Phaidon.

- BONELLO, Deborah (2005) Inside Design & Media: Art in Advertising: The dark art shows its colours: some say inside every copywriter is a frustrated novelist struggling to get out. But perhaps the difference between advertising and fine art is illusory, say Deborah Bonello in The Guardian, 14 March 2005

- Fox, James. 2020. Age of the Image. Series 1: Episode 3: Seductive Dreams. [TV Broadcast] BBC Four, 16 March 2020.

- FREBERG, Karen. GRAHAM, Kristin. McGAUGHEY, Karen. FREBERG, Laura, A. (2010) ‘Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality’ in Public Relations Review. 37(1), 90-92.

- HAENLEIN, Anadol (2020) ‘Navigating the New Era of Influencer Marketing: How to Be Successful on Instagram, TikTok, & Co’. California management review 63(1), 5–25.

- JHALLY, Sut (2017) Advertising At the Age of an Apocalypse. [Film]

- KHAMIS, S. ANG, L. AND WELLING, R. (2017) ‘Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers’ in Celebrity Studies, 8(2), 5.

- KIETZMANN, Jan. H. SILVESTRE, Bruno, S. McCARTHY, Ian, P and PITT, Leyland, F. (2012) ‘Unpacking the social media phenomenon: towards a research agenda’ in Journal of Public Affairs 12(2), 115.

- KL, Chung-Wha &, KIM, Youn-Kyung (20190 ‘The Mechanism by Which Social Media Influencers Persuade Consumers: The Role of Consumers’ Desire to Mimic’ in Psychology & Marketing 36(10), 905–22.

- KRASHINSKY, S. (2010) ‘Happy Together: art and outdoor advertising’ in The Globe and Mail. [Online] Available at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/industry-news/marketing/happy-together-art-and-outdoor-advertising/article4327362/ Accessed 17.11.20

- MANOVICH, Lev. (2016) Instagram and The Contemporary Image in Academia.edu. [Online] Available at https://www.academia.edu/34706553/Instagram_and_Contemporary_Image [Accessed 25.11.20]

- MESSARIS, Paul (1996) Visual Persuasion: The Role of images in Advertising. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- NEWBERRY, Christina and McLachlan, Stacey (2020) ‘Social Media Advertising 101: How to get the most out of your ad budget’ in HootSuite [Online] Available at https://blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-advertising/ Accessed 23.11.20

- SCHROEDER, Jonathan (2013) ‘Snapshot aesthetics and the strategic imagination’ in Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture. 18. Available at http://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/snapshot-aesthetics-and-the-strategic-imagination/ [Accessed 25.11.20]

- SWIFT, Rebecca (2015) ‘Advertising Photography’ in Oxford Art Online. Available at https://www-oxfordartonline-com.ezproxy.falmouth.ac.uk/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7002274532 [accessed 12.11.20]

- TUTEN, Tracy L. (2021) Social Media Marketing. 4th edition. London: Sage Publications.

- VAN, DRIEL, L. and DUMITRICA, D. (2020) ‘Selling brands while staying “Authentic”: The professionalization of Instagram Influencers.’ in Convergence. P1

- ZARRELLA, Dan (2010) The Social Media Marketing Book. California: O’Reilly Media.