Crossing The Boundary Between The Surveyed and The Seen

By Leila Ghobadi-Ghadikolaei (11th June 2021)

Abstract

This dissertation focuses on surveillance and voyeurism in photography. The argument debates the necessity of surveillance imagery against the invasion of privacy that voyeuristic work confronts. Drawing on the work of Michael Wolf, Weegee, Merry Alpern and Sophie Calle as key examples, this dissertation compares the effect of surveillance photography versus voyeuristic photography. In addition, the argument examines deeper the aspect of control that surveillance provides within society, including how it alters behaviour, referencing the work of Trevor Paglen. Furthermore, the debate considers how privacy is breached through voyeurism and compares the balance between this control and invasion. Finally, the discussion references the work of Edward Hopper, in terms of painting’s ability to be voyeuristic. Through comparing his practice to Karin Jurick, Richard Tuschman and Thomas Struth, the dissertation discusses how painting can subvert traditional expectations and align itself to the photographic world. Overall, the dissertation aims to consider how surveillance fits into the society of the 21st century, influenced by modern concerns of technological developments and sacrificing information. Through use of theorists and key writers, such as Foucault, Phillips and Sontag, the discussion focuses on how the public navigate the relationship with constant observation, and photography’s role within this.

Key Words: Surveillance, Voyeurism, Privacy, Control, Boundary

Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Brief Considerations on The Nature of Photography as a Tool of Surveillance and Voyeurism

- Chapter 1: The Omnipresence of Surveillance and the Intrusion of Voyeurism

- Chapter 2: The Undefined Boundary of Surveillance In the Public Realm

- Chapter 3: Edward Hopper: The Voyeuristic Painter

- Conclusion

- References

- Bibliography

List of Figures

- Cover Page: ALPERN, Merry. 1994. Untitled. From: Dirty Windows. 1994.

- Figure 1: HIKVISION. 2016. Hikvision Singapore.

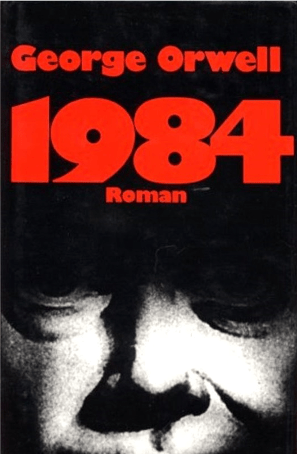

- Figure 2: GÜTERSLOH. 1995. George Orwell 1984 Roman Hardback Cover.

- Figure 3: SKEEN, W.H.L. 1880. Group of Veddahs.

- Figure 4: HALE, Luther. 1860. Portrait of Man and Woman.

- Figure 5: CHABAD SYNAGOGUE. 2019. Court Evidence of Surveillance Footage from the California Synagogue Shooting.

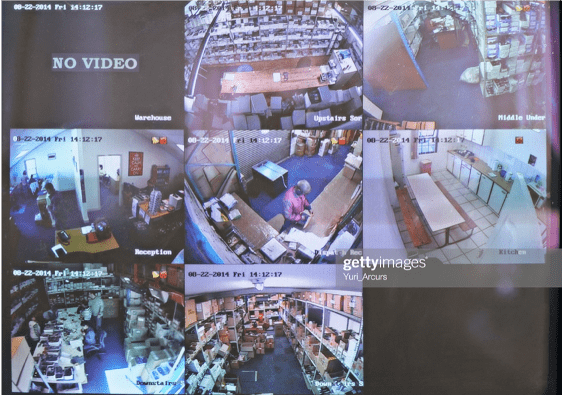

- Figure 6: ARCURS, Yuri. 2014. Keeping an eye for security – Stock Photo.

- Figure 7: WOLF, Michael. 2010. 23. From: A Series of Unfortunate Events. 2010.

- Figure 8: WOLF, Michael. 2010. 8582. From: A Series of Unfortunate Events. 2010.

- Figure 9: HENNER, Mishka. 2011. St Haagsche Schoolvereeniging, Den Haag. From: Dutch Landscapes. 2011.

- Figure 10: WEEGEE. 1945. Lovers at Palace Theater II. From: Movie Theaters.

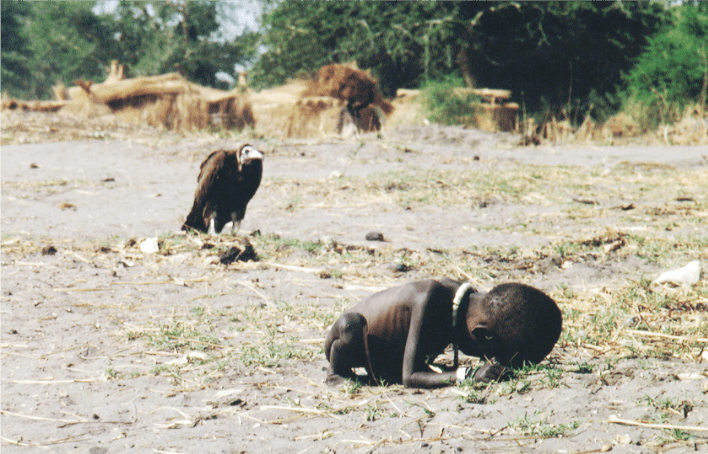

- Figure 11: CARTER, Kevin. 1993. Starving Child and Vulture.

- Figure 12: ALPERN, Merry. 1994. Untitled. From: Dirty Windows. 1994.

- Figure 13: ALPERN, Merry. 1994. Untitled. From: Dirty Windows. 1994.

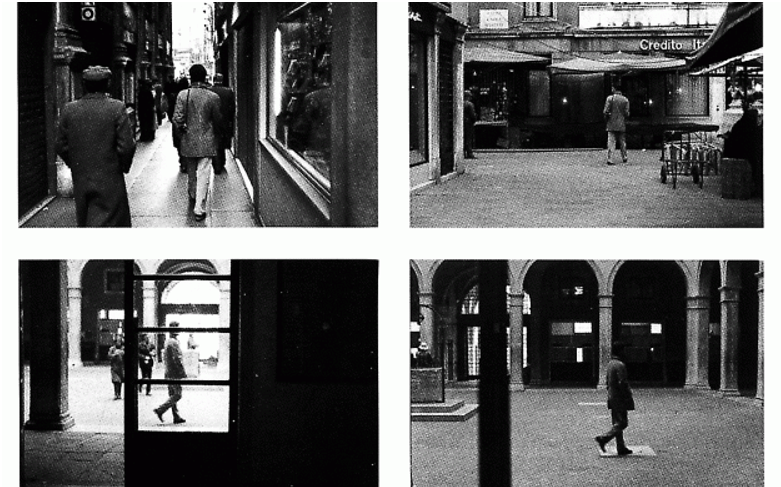

- Figure 14: CALLE, Sophie. 1988. Untitled. From: Suite Vénitienne. 1988.

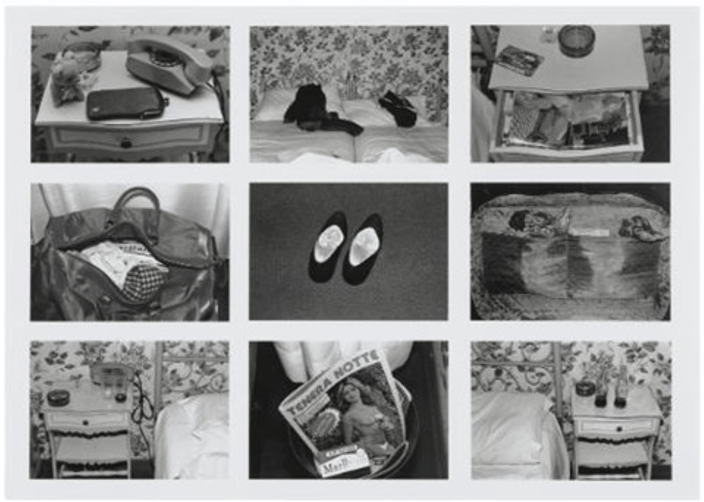

- Figure 15: CALLE, Sophie. 1983. Hotel, Room 26. From: The Hotel. 1983.

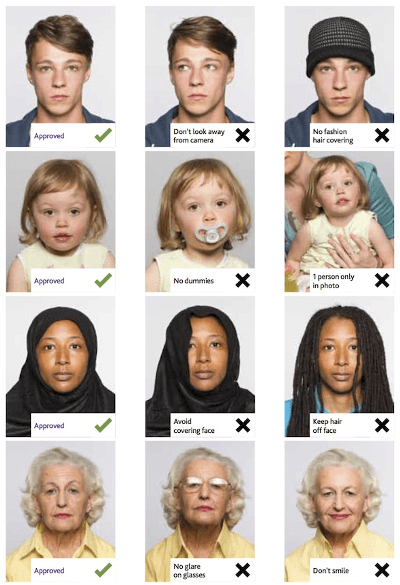

- Figure 16: GOV.UK. Date Unknown. Good and Bad Examples of Printed Photos.

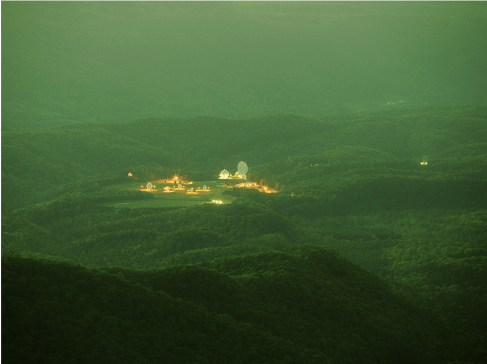

- Figure 17: PAGLEN, Trevor. 2010. They Watch the Moon.

- Figure 18: PAGLEN, Trevor. 2016. NSA-Tapped Undersea Cables, North Pacific Ocean.

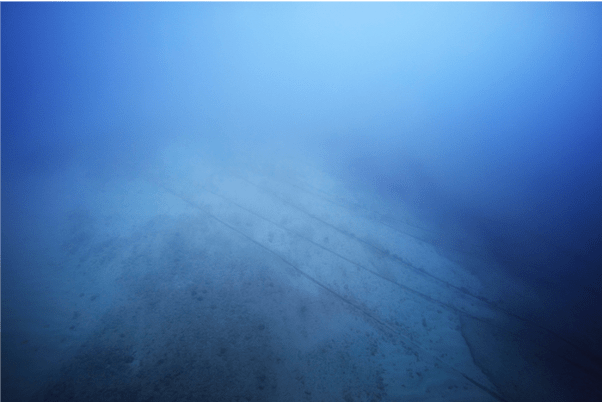

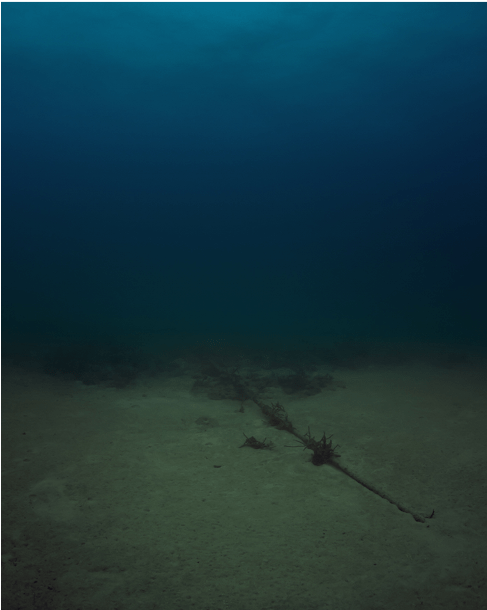

- Figure 19: PAGLEN, Trevor. 2015. Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1), NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable, Atlantic Ocean.

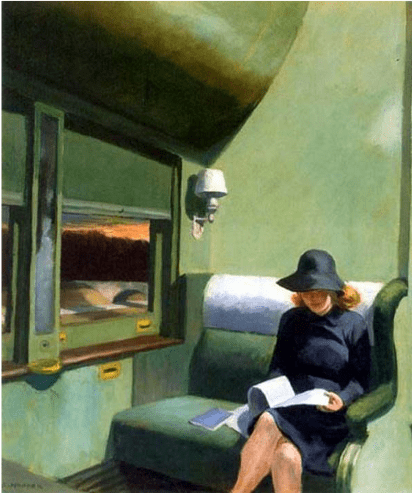

- Figure 20: HOPPER, Edward. 1938. Compartment C Car.

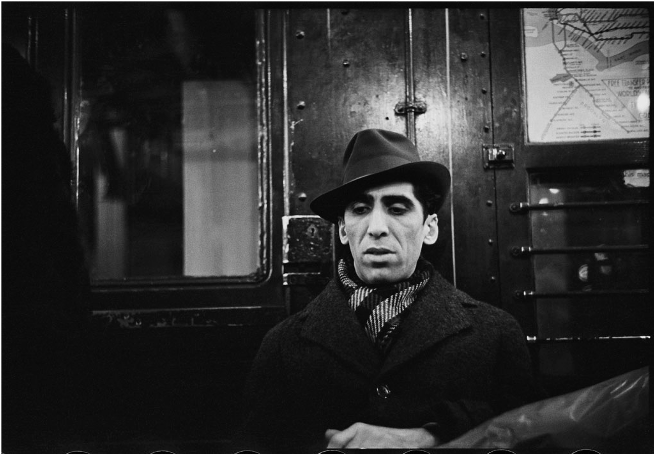

- Figure 21: EVANS, Walker. 1936-1941. From: Many Are Called.

- Figure 22: HOPPER, Edward. 1952. Morning Sun.

- Figure 23: TUSCHMAN, Richard. 2014. Morning Sun. From: Hopper Mediations.

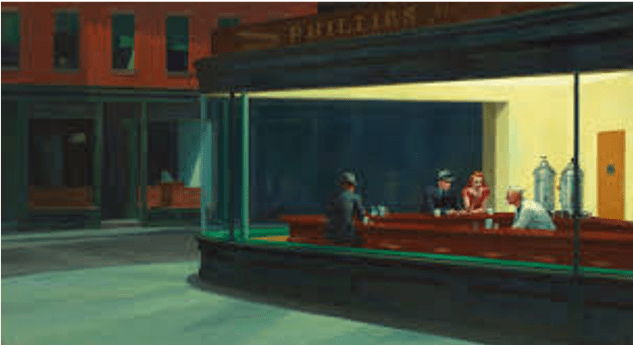

- Figure 24: HOPPER, Edward. 1942. Nighthawks.

- Figure 25: MENDES, Sam. 1999. Jane Undressing Window Scene. From: American Beauty.

- Figure 26: JEUNET, Jean-Pierre. 2001. Amélie Watching Mr Dufayel At His Window. From: Amélie.

- Figure 27: HITCHCOCK, Alfred. 1954. Rear Window Opening. From: Rear Window.

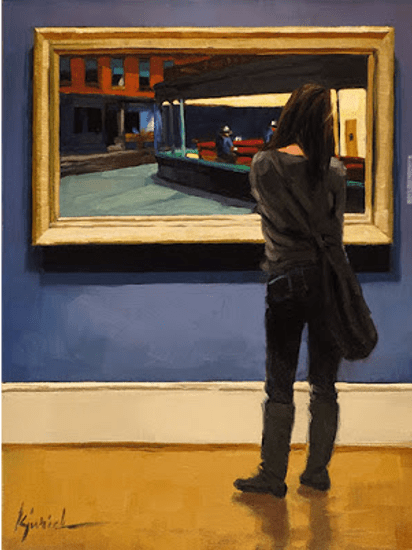

- Figure 28: JURICK, Karin. 2006. Hopper. From: ArtistZ.

- Figure 29: STRUTH, Thomas. 1990. Art Institute of Chicago I. From: Museum Photographs.

- Figure 30: JURICK, Karin. 2006. Renoir. From: ArtistZ

Introduction

In defining surveillance and voyeurism “we might say they are two sides of the same coin – voyeurism being personal, the product of a wilful individuality… while surveillance is impersonal” (Badger, 2010: 87). Since the invention of photography, it has always been true that “to collect photographs is to collect the world” (Sontag, 2008: 3); however, the span of this collection and documentation of human existence has never been to the degree and volume that it is currently. Foucault comments “our society is one not of spectacle but of surveillance” (1991: 217), which remains increasingly relevant to the current social climate. With developments in facial recognition technology and 350 million security cameras worldwide (SDM, 2016), I believe that surveillance is a key topic of debate in the 21st century, especially in the last year. This is due to the rapid developments of surveillance technology in China and the increasing discussion around the topic in other countries. As a species we are at the culmination of recorded existence and verification by photographic devices (Figure 1)

Moreover, the understanding that “the visual image is possibly the dominant mode of communication in the late twentieth century” (Edwards, 1992: 3) is still applicable. A key aspect of this relates to the tourist gaze and ability of the average person to document at their own accord. Furthermore, the existence of social media platforms such as Instagram where “the majority of Instagram authors capture and share photos that are of interest to the author” (Manovich, 2017: 31) is relevant. In this way, it is natural to question purpose and necessity of this technology, as well as subjective boundaries of acceptance, particularly when this is beyond our control.Therefore, this dissertation is relevant to the modern day due to the focus on social acceptance of surveillance and voyeurism, as well as photography, in a world of growing observation.

Firstly, I will touch on the nature of photography as a tool of observation, discussing photography as a window for viewers. I will build upon the reality disclosed and depicted, including early anthropological documentation. Next, in Chapter 1, I will discuss how “the whole world is satelized” (Baudrillard, 1994: 35). Through acknowledging how “photographic images are pieces of evidence in an ongoing biography or history” (Sontag, 2008: 166) I will propose how I believe surveillant documentation is inescapable. I will discuss how surveillance inevitably happens whereas voyeurism crosses a viewer’s comfort.

Furthermore, I will link how photographers use surveillance techniques and concepts to create work, making observations about people; as well as work lending itself to a voyeuristic tone and the way in which I think this pushes viewers too far. Considering the themes in George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), “we need to ask ourselves whether the future society we want to live in is one which constantly watches its citizens” (Thomas, 2019) (Figure 2). Therefore, I think it’s important to comparatively argue how voyeuristic photography and surveillance photography are received. Also, “the surveiller expects to be in a relation of power over what he or she surveilles” (Kember in Lister, 1995: 116) is a factor of debate when considering surveillance in this chapter. I argue the importance of questioning roles of power between the viewer and the viewed, and how this affects acceptance of imagery.

Then, in Chapter 2, I will argue for the necessity of observation and control through surveillance. However, I will discuss issues with observation related to absence of public awareness and social media. Related to this, Philip-Lorca diCorcia makes a good point that “there is no expectation of privacy in a public space anymore in this world… in a way it’s about what you do with those images” (2010). This reflects how we understand that public and private spaces are separate and must accept this, whilst also touching on the notion that what is done with images is important. To expand upon this, my argument will acknowledge necessity of surveillance, whilst also discussing the rights to awareness the public has of what happens with these images and videos of us; such as the long-term storage and whether we are being actively watched or passively recorded.Furthermore, in a society that is becoming more like Orwell’s dystopia, the idea that “so long as they are not permitted to have standards of comparison, they never become aware that they are oppressed” (Orwell, 1989: 216) appears more relevant. In this chapter I will also argue how our awareness of the prevalence of surveillance affects our opinion and acceptance of it.

Finally, in Chapter 3, I will focus on Edward Hopper’s paintings as a case study. I will discuss the voyeuristic nature of photography in more depth, touching on the ability of paintings to be uncharacteristically voyeuristic and the relation of windows in paintings, photography and film. Furthermore, I will debate depicted realities and how the purpose of observation is questioned

Brief Considerations on The Nature of Photography as a Tool of Surveillance and Voyeurism

A key aspect of photography is that “it establishes not a consciousness of the being-there of the thing… but an awareness of its having-been-there” (Barthes, 1977: 44). Thus, I acknowledge that photography is rooted in the trace. Furthermore, referring to conceptions of photography Szarkowski asks “is it a mirror, reflecting a portrait of the artist who made it, or a window, through which one might better know the world?” (1978: 25); I would argue that it is representative of both. Viewers perceive photographs as windows into the world and it is in the nature of images to reveal, both about the photographer and the subject photographed.

Sontag observed that “reality as such is redefined – as an item for exhibition, as a record for scrutiny, as a target for surveillance” (2008: 156). This view is mirrored by “photography cannot ignore the great challenge to reveal and celebrate reality” (Abbott in Tagg, 1988: 156). Surveillance as a form of photography follows the same role in recording reality, although for more lawful and controlling purposes than contemporary photography.

The ability of surveillance to record us holds the same power to confirm existence and document, as that of 19th century anthropological photographs (Figure 3 & Figure 4), photography has always been inherent in showing the real, albeit not always the truth. Said touches on this related to Orientalism and the West’s tendency to convert the view of the East into an ideology of Western superiority; “the tradition of experience, learning, and education that kept the Oriental-colored to his position of object studied by the Occidental-white, instead of vice versa” (1979: 228). The fabricated reality depicted by Western photographers of the Other in anthropological imagery, reflects the absence of truth in photographical representation.

Although, photographs have the ability to disclose information beyond description, meaning they are key in surveillance imagery. Moreover, Bate says “social truth was embodied in the modern technological process of “documenting”” (2016: 59). The reality surveillance discloses is assured to such a degree that it is able to be used in legal trials as a form of evidence (Figure 5) I think that this is related to the understanding society has, that surveillance imagery is untampered with and pure documentation of human behaviour.

Chapter 1: The Omnipresence of Surveillance and the Intrusion of Voyeurism

In my opinion, it is not a question of should surveillance exist, rather acknowledgement that it does, as well as a response to how photography fits into this concept. Focusing on inevitably of surveillance ultimately reflects the concept that “photography is nearly omnipresent, informing virtually every arena of human existence” (Ritchin, 1990: 1). However, the comparative argument considers the breach of privacy I believe voyeuristic work holds, and the confrontation of our scopophilia that affronts us. As Bate described “… the scopic drive is in this sense a source of conscious and/or unconscious pleasure” (2016: 214), in this way my argument questions when this pleasure breaches privacy.

Furthermore, I oppose Phillips’ opinion that “our culture appears to be accommodating itself to the fact of surveillance and no longer considers voyeurism the danger it was in the past” (2010: 15), in reference to medical concerns of the sexual nature of voyeurism. Whilst I believe we are becoming more accommodated to surveillance, due to it becoming part of our subconscious awareness, I think we have social codes on what is acceptable to look at and what is not. Also, acceptance of a surveillance world relates to Adam Curtis’ 2016 documentary HyperNormalisaiton, whereby we live in a constructed fake world. The purpose of this suggested by Curtis is “to spread a state of bewilderment and powerlessness across the globe” (Adams, 2016) which I believe surveillance cameras fit into; their omnipresence is unfathomable to the public, leading to the overwhelming feeling of powerlessness.

Sontag commented “photography is essentially an act of non-intervention” (2008: 11); I believe that surveillance and particularly surveillant photography is a reflection of this concept. As a society, to a degree we have accepted that in public spaces we are watched – “he is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication” (Foucault, 1991: 200). My view is not only is this accepted but often it’s encouraged as it leads to the feeling of public safety. Therefore, I think that we are used to being observed at a distance, and this leads to acceptance. (Figure 6)

In terms of this, my opinion is that surveillance is subconsciously registered. Related to photography, we consider the surveillant distance the camera can offer to also be advantageous as “we want the photographer to be a spy in the house of love and of death, and those being photographed to be unaware of the camera” (Sontag, 2003: 50). Sontag refers to our expectation of photography as a spy and in this way surveillance photography succeeds. Moreover, we acknowledge our own fascination with photography as a medium to look into untouched lives of others.

In reference to Kember’s comment earlier regarding a surveiller’s power, I believe that this also applies to photography; as viewers we understand that we’re in power over those photographed due to our awareness of looking. However, I think viewers are morally reassured when looking at images of people in public spaces, again, due to understanding that they could be a witness.

A key example of work we’re likely to be more comfortable with is Michael Wolf’s 2010 project A Series of Unfortunate Events (Figure 7). The series which looked “for anything weird or bizzare that had been captured by the ravenous cameras” (Casper, 2011) of Google Earth’s vans is not only comfortable for viewers to look at, but often amusing and curiosity-evoking. In my view, this comfort is due to the understanding that Wolf photographs images already taken, similar to Jon Rafman’s The Nine Eyes of Google Street View (2016) and Doug Rickard’s A New American Picture (2012). I agree that Google Earth seemingly possesses an “indifferent gaze” (Dyer, 2012) which Wolf uses advantageously, allowing a viewer to feel fascinated.

In addition, I argue that Wolf’s series is accepted due to the level of detachment provided in looking. Related to surveillance, particularly Jeremy Bentham’s 18th century panopticon, Foucault comments “it had to be like a faceless gaze that transformed the whole social body into a field of perception” (1991: 214). This also relates to Google Earth imagery as viewers consider the technology a source of information with an ambiguous gaze. The pixelated style and context give permission to enjoy the work, without concern about why the photographer did not intervene.

Furthermore, societal understanding of Google Earth means that the viewer is less concerned about purposes of the original imagery. In addition, the blurred or absent faces also reassure the viewer that personal identity is not at jeopardy, demonstrated in Figure 8. Related to my argument, this reinforces that distance and anonymity of surveillance bring a certain level of observational comfort.

In comparison, Mishka Henner’s 2011 Dutch Landscapes project also uses Google Earth. (Figure 9) With focus on significant Dutch locations, such as government sites, Henner acknowledges how censorship is “imposed on the landscape to protect the country from an imagined human menace” (2011). Although, I think there is a sense of hypocrisy in that governments enforce censorship for their buildings, but expect complete access to the public, I also understand necessity of national security. Alike to Wolf’s work, the series acknowledges how “the Google eye is so ubiquitous” (Medina, 2013) and again ignites the viewer’s curiosity.

Similarly, I believe that Arthur Fellig’s (Weegee) 1940s Movie Theaters series reflects viewer’s acceptance of observation. (Figure 10). In terms of the series, “the photographs capture everything that is unseen during a movie screening” (Brennan, 2015); in this way, Weegee mirrors the curiosity into lives of others that Wolf provides. In my view, this is due to the fact that Weegee’s images are not shocking. Sontag commented that in terms of journalism “images were expected to arrest attention, startle, surprise” (2004: 19) and I think the familiarity of the series prevents this.

Therefore, I argue that Wolf and Weegee’s work are examples of how “photographs depict realities that already exist” (Sontag, 2008: 122). In my opinion, the understanding that the human behaviour is in a public space and the viewer could’ve been a witness reassures those looking at the work, alleviating feelings of guilt or intrusion. This also relates to citizen journalism; I believe a viewer is less likely to question if it’s acceptable to be looking as they identify themselves as a fellow observer. This links to the urge to photograph as “they strive to record what’s happening from their perspective or vantage point” (Allan in Hájek, 2014:176). Related to this, Sontag made a key point that “needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted” (Sontag, 2008: 24) and I believe observant photography is evidence of this.

In addition, Gill comments “any act of observation implies a certain detached alertness” (in Phillips 2010: 241) which aligns itself with viewers of Weegee’s, Wolf’s and Henner’s work, as both photographer and viewer engage with detached vigilance. Furthermore, I think we don’t consider viewing of this kind a threatening act, therefore the power viewers possess over the subject is not as big of a concern. In addition, as viewers assume photographers to have responsibility and power in choosing to take images, viewers feel able to assume the photographer is accountable for their concerns and guilt, whilst still acknowledging their right to look. A key example of this is Kevin Carter’s Starving Child and Vulture (1993) photograph, which caused criticism from viewers who argued he should have intervened rather than document. (Figure 11)

However, the question of “does documentary inevitably create a prurient voyeurism for example, an unethical desire to look into the lives of others?” (Bate, 2016: 61) must be asked when considering documentary imagery. It’s important to debate when scopophilia breaches a boundary for viewers and causes discomfort. Moreover, in my opinion, when we feel that we’ve overstepped the boundary of privacy we begin to consider why we desire to look and our moral stance in relation. In a society where we are watched, it is voyeurism with its tendency for “invasive looking” (Phillips, 2010: 6) that I think many viewers are opposed to. Although we understand that “we watch, and we are watched” (Phillips, 2010: 6) I think voyeurism holds a degree of closeness that viewers often wish to disengage with in terms of photographic work.

In my opinion, a key example of this boundary being crossed is Merry Alpern’s 1994 series Dirty Windows. (Figure 12) Over six months Alpern produced intimate images of a secret New York lap-dance club that she described as having “something to do with wanting to understand how people connected, no matter the circumstance” (Alpern in Vermare in Cotton, 2018: 130). This is understandable to any viewer due to our inherent curiosity about others and human interaction, what’s interesting is the extreme to which Alpern considers this in her work.

Baker comments “our entire life is spent peeping into windows and listening at the keyhole – that’s our craft” (in Phillips 2010: 208) in regard to photography. I agree with this statement in the sense that it’s always the photographer’s nature to be curious, which drives them to pursue an image. Furthermore, the idea of photography being a window is inherent within the medium, as mentioned earlier, suggesting the inevitability of looking to be about seeing into an aspect of the world. This is certainly true of Alpern, however I think that the nature of the series brings into question a viewer’s own morals. In my view, it is not necessarily the content of the imagery which offends, as we understand the concept of pornography and a viewer’s enjoyment of watching others engage in sexual activities. (Figure 13).

Therefore, I think it’s the way in which those being photographed are unaware their intimate acts in a private space are now available for viewing beyond the window itself. Unlike Wolf and Weegee’s works, the activities portrayed in Alpern’s photographs aren’t within the public sphere and therefore the subject hasn’t consented to this visibility. I believe the act of looking at people having sex in a private space is understood as culturally unacceptable, and therefore Alpern’s series doesn’t follow our social normalities. I argue that when viewers breach societal rules, in any regard, they feel unease and shame. Moreover, this relates to conditioned behaviour through the idea that “perhaps inevitably in cultural life a child’s voyeuristic enthusiasm is curbed by parents and other adults, who impose social rules about when looking is appropriate or not” (Bate, 2016: 77).

Similarly, in my opinion Sophie Calle’s work produces the same unease of looking as Alpern’s. As demonstrated in Figure 14, she followed a man in Venice for 12 days. Although the man was aware of what she planned to do from the beginning, I think viewers still feel a sense of forbidden looking. In my view, there is the sense that Calle invades the subject, especially in Figure 15 where she used her job for the intent of her photography. Viewers don’t wish to think about the possibility of being followed or their trust in a stranger to be taken advantage of. In this way, I believe that Calle’s work offends viewers on behalf of the subject as they wish to avoid hypocrisy or a double standard. Related to this, Ulin comments that “for Calle, the idea is to push the bounds of propriety, to go where one wouldn’t ordinarily go” (2015), whilst she succeeds in this, she also forces the viewer to engage in this. The sense of stalking the images in Suite Vénitienne possess, also seen in The Hotel, cross boundaries of acceptable looking for viewers.

The idea that “we have expectations concerning a particular circle of unfamiliar people whom we might meet, and we have expectations concerning how these people will behave towards us” (Rössler, 2005: 115) is true in the sense that “we do not expect our being seen to be recorded on film and thus converted into something that can be shown in public” (Rössler, 2005: 115). I think Calle’s work directly relates to this, making viewers uncomfortable as they acknowledge that we put trust in strangers and don’t expect them to breach that.

Therefore, I think that as viewers we’re comfortable with surveillance work like Wolf’s and Weegee’s due to the way it provides us with distance from the subject. Furthermore, the acknowledgement that the subjects are already in a public space frees viewers of guilt, as they believe themselves to be possible witnesses already. In direct contrast, I believe that Alpern and Calle’s voyeuristic style is more likely to offend. This is due to the sense of privacy being breached in private spaces, causing viewers to feel morally incorrect. Furthermore, the viewer is uncomfortable for the subjects who expect privacy, which I believe makes the feeling of forbidden looking prevalent. However, building upon this discussion, purposes of surveillance and observation beyond photographic curiosity are questionable, relating to boundaries that are defined in terms of privacy.

Chapter 2: The Undefined Boundary of Surveillance In the Public Realm

In terms of surveillance, I think the purpose of technology to control the masses is necessary, however public knowledge and ability to regulate being watched is an issue. My argument is, that defining boundaries related to presence and intrusion of surveillance within society is the key problem. The comment that “privacy has been defined by what it protects or provides, namely dignity, personhood, individuality, autonomy” (Phillips, 2010: 55) stands true, however I believe surveillance isn’t as simply validated by this.

To a degree, the concept that “a subjected being, who submits to a higher authority, and is therefore stripped of all freedom except that of freely accepting his submission” (Althusser, 1984: 56) is true. Although surveillance arguably limits our free will, I think it simply reinforces our natural public behaviour. Moreover, use of surveillance aids in deterring illegal and dangerous behaviours beyond societal expectations of public behaviour. However, I also argue that surveillance presence has led to construction of socially accepted behaviour beyond taught morals; such as the understanding that you wouldn’t steal due to being caught on camera.

In terms of photography, I believe that claiming street photography can be truly candid is false; in public people provide certain personas and more formal behaviour. Foucault commented “we are neither in the amphitheatre, nor on stage, but in the panoptic machine” (1991: 217) which I think is partly true for the 21st century culture of observation. However, the effect of the panoptic society also means we’re on a stage in a sense, through how we portray altered versions of ourselves.

Moreover, in my opinion, control of the public provides benefits such as safety and as Lister says, “surveillance and classification are forms of social control which operate through the acquisition and organisation of information” (1995: 96). A key example of this information aspect would be passport photos (Figure 16). I believe that the use of documentation of people for safety is accepted and supported. Surveillance holds a similar power in classifying us for identification. During research it became clear that positive evidence related to spy photography and drones was virtually non-existent. In my view this makes sense, due to modern concerns related to surveillance. However I think that benefits are often overlooked.

Despite the benefits, the point that “it generates a degree of conflict between the control of and control on behalf of individuals and communities” (Kember in Lister, 1995: 117) is valid. In my view, the issue with surveillance is regulation. The public are most affected by surveillance, however they don’t possess power to dictate acceptable standards. With facial recognition technologies being introduced, as well as gait recognition, which has the ability to identify you from your walk, the issue of pushing surveillance too far comes into question. As Phillips comments “voyeurism and surveillance provoke uneasy questions about who is looking at whom, and for what purposes of power or pleasure” (2010: 6) which becomes increasingly relevant to modern humanity.

Furthermore, I think that the problem doesn’t only occur in public but also through use of phones where “it has now become commonplace to hear of Google using individual searches to sell targeted ads, Twitter promoting content on your feed based on who you follow, or Facebook data being scraped to enhance political campaigns” (Stuart, 2019). Whilst many users still hope for mobile phones to be possessions of privacy, the reality is that our information is worth a lot and is now being surveilled and sold. I argue that in the 21st century we must come to understand that as soon as we have a phone we have sacrificed our privacy. Also, I believe this extends to visual culture as information related to us is documented through photographs and shared online.

As Ritchin comments in reference to media, “many advertisers have since abandoned such publications, leaving them behind for the more selective reach of search engines plugged in to even more individualized interests” (2013: 20). I think the act of being online is transactional; public gain of unlimited worldwide information and connections, in trade for the companies’ gain of private sensitive information. The problem is “we don’t know if they’re potentially subverting security measures in order to facilitate spying on us” (Granick in Belkhyr, 2019), suggesting how the public have an absence of knowledge in terms of surveillance laws and their rights. In my opinion, photography in its surveying nature, is also part of the issue as many people don’t know their rights related to images.

In terms of photography, Trevor Paglen’s work focusing on surveillance and the digital world, comments on issues to do with privacy and understanding of the internet. (Figure 17) In reference to the internet, Paglen comments “it’s this thing that nobody can quite describe that seems like it’s nowhere but everywhere at the same time” (in Chapman 2016). I think that his work looking at US intelligence buildings and underwater internet cables aids viewers in understanding physicality of surveillance and the internet.

I think that Paglen’s work brings into question the scale of the photographic surveillance network and creates a wider picture of this reality. The intangibility of the internet makes the concept of being watched difficult to grasp, however the physical evidence shown in Paglen’s photographs reinforces the real (Figure 18). Furthermore, “his is a practice broadly underpinned by an investigation into the relationship between vision, power and technology” (Clark, 2019) and in this way brings the intent of surveillance into question. My view is that the intention of surveillance and those that watch us is questionable, largely due to the public’s absence of knowledge surrounding this.

I believe that due to Paglen’s work suggesting the vast scope of the surveillance network, viewers consider true intentions of those observing us, as mentioned earlier. (Figure 19) My view is that Paglen’s work is successful in revealing part of this unknown world. However, as many companies who hope to gain access to our information online are private, we may be unable to truly realise these intentions. The physical evidence of surveillance in the photographs suggests how truth regarding the topic is concealed from us, and the use of the internet has caused distraction from the reality of being watched. This relates to the idea of the image world as “the circuits of surveillance cameras are themselves part of the décor of simulacra” (Baudrillard, 1994: 76). We understand we are being watched, however we do not know the extent of this. Furthermore, we are drowned in online information, a lot of which is irrelevant or distracting, preventing our ability to fully comprehend the truth of our sacrifice.

Leading on from this discussion regarding privacy, the concept of voyeurism in visual culture becomes key in understanding the ways of invasive looking and how this instinct is ingrained in creative representations

Chapter 3: Edward Hopper: The Voyeuristic Painter

Photography’s nature is voyeuristic, “the photographic attraction resides in a visceral sense that the image mirrors palpable realities” (Ritchin, 1990: 2). In this way, photography has always felt close to, a part of, or even synonymous with reality. Whilst it is rooted in the trace as mentioned earlier, photography is not necessarily a depiction of reality, rather just the real. Moreover, despite Ritchin’s comment that “without this reliance on palpable fact, however, photographic currency, like that of painting, becomes the imagination” (1990: 2), some painting is able to mirror the real to a degree. A key example of this would be Edward Hopper’s realism paintings depicting American life. (Figure 20)

In relation to photography, Gordon comments “voyeurism is inherent in the medium. It’s a voyeuristic medium, unlike, say painting, which can be voyeuristic but is not necessarily” (2010). However, Hopper’s work is evidence of the way in which painting can be voyeuristic; I propose that paintings help us to understand photographic voyeurism due to developing awareness of composition and the choices painters make, similar to choices a photographer makes. I think this strongly links to the unusual style of Hopper’s work and causes the viewer to feel slightly unnerved by the paintings due to the realistic aesthetic.

Reminiscent of Walker Evans’ Many Are Called (1936- 1941) series (Figure 21), the paintings appear to the viewer as a photograph would, reflecting Hopper’s distinct style in the ability to paint like a photographer captures. (Figure 22) The comment that “the ambiguous, narrative richness of Hopper’s paintings – combined with their subtle, anxious energy – has given them a timeless quality” (Thackara, 2018) is valid. In this sense, the viewer has an understanding of the feeling of familiarity that Hopper’s paintings release. Furthermore, the photographic recreations of Richard Tuschman’s Hopper Mediations series prove the easy transition of Hopper’s work into photography. (Figure 23). Tuschman comments on Hopper’s paintings saying, “he created quiet scenes that are psychologically compelling with open-ended narratives” (2014); the reflection of the work as scenes containing narratives, aids in the relation to photography due to the way it suggests a constructed story.

Related to my earlier point regarding photography being a window into the world, I argue that Hopper’s work acts also as a window, only in a more clearly perceived way. Goodrich observed this by saying “many of his city interiors are seen through windows, from the viewpoint of a spectator looking in at the unconscious actors and their setting- a life separate and silent, yet crystal-clear” (1978: 105).

An example of Hopper’s windows is his Nighthawks painting demonstrated in Figure 24. I think that this painting is synonymous with Hopper due to the way in which it symbolizes how “his works depict urban loneliness, disappointment, even despair” (Peacock, 2017). The identification the viewer feels, especially for those in mid-20th century America, likens itself to photography as viewers understand images through their own experiences and associations.

In addition, the use of windows is not only seen in Hopper’s paintings and Alpern’s photographs, but also in film. A key example of this window-based voyeurism is in American Beauty (1999) directed by Sam Mendes and Amélie (2001) by Jean-Pierre Jeunet. Moreover, in Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) the viewer sees how the use of windows are key to the plot; “by sharing this voyeuristic activity with the audience, Rear Window shows Hitchcock’s view on voyeurism that is a universal pleasure that all human beings pursue” (Hopkins in Saporito, 2015). These similarities reflect how important the concept of observation is within wider visual culture. (Figure 25, Figure 26 & Figure 27)

Also related to voyeurism within painting, Karin Jurick’s ArtistZ (2006) series (Figure 28) depicts observations regarding how viewers look at artwork in the gallery context. In a similar way to Hopper, Jurick’s painterly observations reflect a photographic nature and cause viewers to second-guess what they are seeing, due to the expectation of them being photographs. Jurick herself comments “I still can’t get enough of it” (in Fauntleroy, 2010) in regards to painting. I believe that photographers possess this same drive to capture, as well as a voyeuristic nature, which causes them to continue working.

Moreover, Jurick’s paintings reflecting photographic tendencies are evidenced by likeness to Thomas Struth’s Museum Photographs (1989-2001). As shown in Figure 29 and Figure 30 their works are relative mirrors of one another existing in different mediums. Regarding the gallery space of his work, Struth commented “it’s not defined like a football stadium or a concert venue. I wanted to capture that interim sense of place” (in O’Hagan, 2011). I think that this links to voyeurism due to the way that viewers are curious about people looking, especially in a gallery space which has the purpose of displaying works to be seen

Linking these works back to Hopper, Goodrich commented “after his early years his oils were composed by a process of imaginative reconstruction in which both observation and memory played parts” (1978: 129) which I think relates to the topic of voyeurism overall. In my opinion, Hopper and Jurick’s works hold familiarity as the viewer is able to identify the representation of the real. The understanding that they have witnessed, and are able to witness, something similar to what is depicted suggests the way in which the works hold a feeling of personal memory. Moreover, I believe that Hopper and Jurick’s styles are evidence in the way in which paintings can possess a voyeuristic nature and make the viewer question purposes of looking, alike to photography.

Conclusion

In summary, surveillance exists and is beneficial in public safety and control. I think we find surveillance photography more acceptable, compared to voyeuristic photography that brings awareness of invasive looking to the forefront. In my view voyeurism offends, as it subverts our learned behaviour.

Moreover, I believe there needs to be improved regulation and public education of surveillance techniques and storage, particularly related to social media, where information has become monetarily valuable to companies. In reference to literature, “as Neil Postman wrote in Amusing Ourselves to Death, comparing the dystopian theories of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley: ‘Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.’ Unfortunately both seem to have been right” (Ritchin, 2009: 90). I agree due to the way the public is unaware of the degree of surveillance and social media’s irrelevance in distracting us. In addition, I have acknowledged photography’s voyeuristic nature and painting’s ability to be. Also, I’ve discussed how visual culture contains the theme of looking and how this is often inherent.

Finally, looking forward to the future of our surveillance society, it brings into question the possibility of a totalitarian state. Lyon commented “if Giddens is right to say that ‘Totalitarianism is, first of all, an extreme focusing of surveillance’ then the enhanced role of new technology within government administration and policing should give us pause” (1994: 11). Whilst the increased prevalence of surveillance is leading to increased regulation questioning, Los commented “the multi-site governance of security, multiple hierarchies and preponderance of networks may not constitute an effective barrier to totalizing forces” (in Lyon, 2006: 74) in reference to widespread use of surveillance. Therefore, I think it’s important to acknowledge, that the omnipresence of surveillance may inevitably be uncontrollable, immeasurable and irregulated, which I think photographic practitioners and theorists will continue to comment upon indefinitely.

References

- ADAMS, Tim. 2016. ‘Adam Curtis Continues to Search for the Hidden Forces Behind a Century of Chaos’. The Guardian. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/z9c7haz [Accessed 31/10/19]

- ALTHUSSER, Louis. 1984. Essays on Ideology. London: Verso.

- BADGER, Gerry. 2010. ‘Through The Eyes of The Voyeur’. The British Journal of Photography. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yypmc4g5 [Accessed 10/10/19]

- BARTHES, Roland. HEATH, Stephen. 1977. Image Music Text. London: Fontana.

- BATE, David. 2016. Photography: The Key Concepts. 2nd edn. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- BAUDRILLARD, Jean. 1994. Simulacra and Simulation. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- BELKHYR, Yasmin. 2019. ‘The Terrifying Now of Big Data and Surveillance: A Conversation With Jennifer Granick’. TEDBlog. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yytzzwyz [Accessed 03/10/19]

- BRADSHAW, Peter. 2000. ‘American Beauty’. The Guardian. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/vlnme9u [Accessed 14/11/19]

- BRENNAN, Aisling. 2015. ‘Chelsea Cinema Shines Light on Weegee’s Movie Lovers’. Observer. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2uettb2 [Accessed 10/09/19]

- CASPER, Jim. 2011. ‘Feature: A Series of Unfortunate Events’. Lens Culture. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y226w344 [Accessed 18/09/19]

- CHAPMAN, Catherine. 2016. ‘The Surveillance Artist Turning Landscape Photography Inside Out’. Vice Magazine. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y3sz7obq [Accessed 11/10/19]

- CLARK, Tim. 2019. ‘Trevor Paglen: From ‘Apple’ to ‘Anomaly’”. British Journal of Photography. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2ty6u89 [Accessed 11/10/19]

- COTTON, Charlotte. 2018. Public, Private, Secret: On Photography & The Configuration of Self. New York: Aperture Foundation.

- DYER, Geoff. 2012. ‘How Google Street View is Inspiring New Photography’. The Guardian. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yy997qxy [Accessed 27/10/19]

- EDWARDS, Elizabeth. 1992. Anthropology & Photography 1860-1920. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- FAUNTLEROY, Gussie. 2010. ‘Karin Jurick: The Way We Are’. South West Art. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y462bffx [Accessed 03/11/19]

- FOUCAULT, Michel. SHERIDAN, Alan. 1991. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- GOODRICH, Lloyd. 1978. Edward Hopper. New York: Harry N.Abrams.

- HÁJEK, Roman. 2014. ‘Citizen Journalism is as Old as Journalism Itself: An Interview with Stuart Allan”. Orca. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y4awlukw [Accessed 01/11/19]

- HENNER, Mishka. 2011. ‘Dutch Landscapes’. Mishka Henner. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y36foh9b [Accessed 27/10/19]

- KEMBER, Sarah. 1995. ‘Surveillance, Technology and Crime: The James Bulger Case’, in Lister, Martin. 1995. The Photographic Image in Digital Culture. 1st edn. London: Routledge.

- LOS, Maria. 2006. ‘Looking Into the Future: Surveillance, Globalization and the Totalitarian Potential’, in Lyon, David. 2006. Theorizing Surveillance: The Panopticon and Beyond. Cullompton: Willan.

- LYON, David. 1994. The Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press.

- MANOVICH, Lev. 2017. ‘Instagram and Contemporary Image’. Academia.Edu. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y6fh6jg6 [Accessed 31/10/19]

- MEDINA, Sammy. 2013. ‘An Artist Finds Government Censorship in Google Earth’. Fast Company. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y4pcmp5o [Accessed 27/10/19]

- O’HAGAN, Sean. 2011. ‘Thomas Struth: Photos so complex “you could look at them forever”’. The Guardian. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2u9o7ev [Accessed 03/11/19]

- ORWELL, George. 1989. Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Penguin.

- PEACOCK, James. 2017. ‘Edward Hopper: The Artist That Evoked Urban Loneliness and Disappointment with Beautiful Clarity’. The Independent. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y34e9kmd [Accessed 12/10/19]

- PHILLIPS, Sandra S. BAKER, Simon. 2010. Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera since 1870. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

- RITCHIN, Fred. 1990. In Our Own Image: The Coming Revolution in Photography – How Computer Technology is Changing our View of the World. New York: Aperture.

- RITCHIN, Fred. 2009. After Photography. New York: W.W. Norton.

- RITCHIN, Fred. 2013. Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen. New York: Aperture.

- ROSSLER, Beate. 2005. The Value of Privacy. Oxford: Polity.

- SAID, Edward. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

- SAPORITO, Jeff. 2015. ‘In ‘Rear Window’, what is Hitchcock’s attitude about voyeurism?’. Screen Prism. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yx6vmckq [Accessed 12/11/19]

- SDM. 2016. ‘Rise of Surveillance Camera Installed Base Slows’. SDM. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y3w4ukza [Accessed 09/10/19]

- SONTAG, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- SONTAG, Susan. 2008. On Photography. London: Penguin.

- STUART, Freddie. 2019. ‘How Facial Recognition Technology Is Bringing Surveillance Capitalism To Our Streets’. OpenDemocracy. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y67mtpee [Accessed 05/10/19]

- SZARKOWSKI, John. 1978. Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

- TAGG, John. 1988. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education.

- TATE. 2010. ‘Exposed: Philip-Lorca diCorcia’. Tate. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2pdmcvc [Accessed 01/10/19]

- TATE. 2010. ‘Exposed: Richard Gordon’. Tate. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2zo48l8 [Accessed 01/10/19]

- THACKARA, Tess. 2018. ‘Understanding Edward Hopper’s Lonely Vision of America, beyond “Nighthawks”’. Artsy. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yxvdnbcr [Accessed 12/10/19]

- THOMAS, Elise. 2019. ‘New Surveillance Tech Means You’ll Never Be Anonymous Again’. Wired. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y3w25qxy [Accessed 05/10/19]

- TUSCHMAN, Richard. 2014. ‘Hopper Mediations’. Richard Tuschman. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y3tswp8s [Accessed 06/11/19]

- ULIN, David. 2015. ‘Sophie Calle Investigates the Distance Between Us in Suite Vénitienne’. Los Angeles Times. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y59ka6zh [Accessed 10/10/19]

Bibliography

- ADAMS, Tim. 2017. ‘Trevor Paglen: Art in the age of mass surveillance’. The Guardian. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/ycar8ue2 [Accessed 14/11/19]

- AESTHETICA. 2016. ‘Art: Cultural Anonymity – Michael Wolf’. Aesthetica. (72) pp. 24-35.

- BARNES, Sara. 2016. ‘Artist Creates Voyeuristic Paintings of Real Museum Patrons Lost in the Beauty of Fine Art’. My Modern MET. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yyxd4hg2 [Accessed 11/10/19]

- BBC. 2019. ‘How Hong Kong Protesters Avoid Police Surveillance’. BBC. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y4973gex [Accessed 04/10/19]

- BURGESS, Matt. 2018. ‘The UK’s Mass Surveillance Laws Just Suffered Another Hefty Blow’. Wired. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y38xt4ub [Accessed 05/10/19]

- BURGIN, Victor. 1979. Photography/Politics: One. London: Photography Workshop.

- CALLIA, Phillipe. 2011. ‘Representing the Other Today: Contemporary Photography in the Light of the Postcolonial Debate (with a special focus on India)’. Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/ss38zbm [Accessed 14/11/19]

- CURTIS, Adam. 2016. ‘HyperNormalisation’ [Documentary]. BBC iPlayer. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2zhswrp [Accessed 31/10/19]

- DE ROSA, Miriam. 2014. ‘Poetics and Politics of the Trace: Notes on Surveillance Practices Through Harun Farocki’s Work’. NECSUS. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y35l69kl [Accessed 02/10/19]

- DYER, Geoff. 2016. ‘Geoff Dyer on Globalization, Inequality and Photography’. Medium. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y6mb3l6g [Accessed 18/09/19]

- ELEPHANT MAGAZINE. 2015. ‘Art as Geospatial Intelligence Gathering’. Elephant Magazine. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y4ewtoom [Accessed 27/10/19]

- FEENBERG, Andrew. FRIESEN, Norm. SMITH, Grace. 2009. ‘Phenomenology and Surveillance Studies: Returning to the Things Themselves’. The Information Society. 25 (2) pp. 84-90.

- FILLINGHAM, Lydia. SUSSER, Moshe. 1993. Foucault for Beginners. New York: Writers and Readers Pub.

- FORBES, Duncan. 2015. ‘Photography and Social Movements: From the Globalisation of the Movement (1968) to the Movement Against Globalisation (2001)/Miklós Klaus Rózsa’. History of Photography. (39) pp. 201-203.

- GOTTHARDT, Alexxa. 2019. ‘How Photographer Kohei Yoshiyuki’s “The Park” Became A Cult Phenomenon’. Artsy. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y545cehs [Accessed 11/10/19]

- HALL, Stuart. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage.

- HASHIM, Lina. 2014. ‘Unlawful Meetings’. Lina Hashim. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/t74v9x6 [Accessed 12/11/19]

- HENSON, Julie. 2010. ‘Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and The Camera Since 1870 at SFMoMA’. HuffPost. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2jwxord [Accessed 18/09/19]

- KALFATOVIC, Martin. 1995. ‘Book Reviews: Arts & Humanities, Edward Hopper’. Library Journal. 14 (120) pp. 171-172.

- LAUGHLIN, Andrew. 2019. ‘The Cheap Security Cameras Inviting Hackers Into Your Home’. Which?. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y4ggnk24 [Accessed 04/10/19]

- LAURENT, Olivier. 2011. ‘Michael Wolf Speaks of His Google Street View Work’. [Video] Vimeo. Available at: https://vimeo.com/20667709 [Accessed 18/09/19]

- LEMAGNY, Jean-Claude. ROUILLÉ, André. 1987. A History of Photography: Social and Cultural Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- LINFIELD, Susie. 2010. The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- LISTER, Martin. 1995. The Photographic Image in Digital Culture. 1st edn. London: Routledge.

- LYON, David. 2006. Theorizing Surveillance: The Panopticon and Beyond. Cullompton: Willan.

- MCCULLOCH, Shannon. 2016. ‘Voyeurism in Rear Window’. The Art of Cinema. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/r4u9azk [Accessed 12/11/19]

- MENAND, Louis. 2018. ‘Why Do We Care So Much About Privacy?’. The New Yorker. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y96p32as [Accessed 11/10/19]

- MORRISON, Blake. 2010. ‘Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and The Camera’. The Guardian. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y3nashjh [Accessed 02/10/19]

- MURPHY, Jessica. 2007. ‘Edward Hopper (1882-1967)’. The MET. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/hy7yrqu [Accessed 12/10/19]

- NORTH, David. 2018. ‘Voyeurism and Subjective Understanding in ”Rear Window”’. University of Chicago. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/v8fejp6 [Accessed 14/11/19]

- NYE, Catrin. 2019. ‘Live Facial Recognition Surveillance “Must Stop”’. BBC. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y3a8yz2r [Accessed 05/10/19]

- PAHWA, Nikhil. 2018. ‘Thought China Was Getting All Big Brother? India’s Not Far Behind’. Wired. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2dkfhb7 [Accessed 05/10/19]

- POWLING, Nick. 2019. ‘AI: The Smart Side of Surveillance’. ComputerWeekly. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/sjd2qzc [Accessed 14/11/19]

- RAFMAN, Jon. 2016. Nine Eyes. Los Angeles: New Document.

- RICKARD, Doug. 2012. A New American Picture. New York: Aperture.

- SCHEWE, Eric. 2018. ‘How Pleasure Lulls Us Into Accepting Surveillance’. JStor. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y4cfvul4 [Accessed 27/10/19]

- STRUTH, Thomas. 2010. ‘Museum Photographs’. Thomas Struth. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y6qse3go [Accessed 11/10/19]

- SULTAN, Larry. 2004. ‘Larry Sultan The Valley’. Galerie Thomas Zander. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yxs2mokl [Accessed 31/10/19]

- TATE. 2010. ‘Exposed: Laurie Long’. Tate. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y4fs9y7l [Accessed 01/10/19]

- TATE. 2010. ‘Exposed: Mitch Epstein’. Tate. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y54gnxy4 [Accessed 01/10/19]

- TATE. 2010. ‘Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and The Camera’. Tate. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yxvp3xfb [Accessed 18/09/19]

- TATE. 2010. ‘Jonathan Olley – Exposed at Tate Modern’. YouTube. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y2t52zsy [Accessed 18/09/19]

- TATE. 2010. ‘Sandra Phillips on Surveillance – Exposed at Tate Modern’. YouTube. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yxpqqf5k [Accessed 18/09/19]

- TAYLOR, Josh. 2019. ‘Plan For Massive Facial Recognition Database Sparks Privacy Concerns’. The Guardian. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y3co7mwy [Accessed 04/10/19]

- VERMARE, Pauline. 2016. ‘Public, Private, Secret – Merry Alpern with Pauline Vermare’. International Center of Photography. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y52oprdl [Accessed 10/10/19]

- WEISS, Sabrina. 2019. ‘Levi’s New Trucker Jacket Paves The Way For Smart Jeans, Thanks to Google’. Wired. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y3h4rm39 [Accessed 04/10/19]

- WOLF, Michael. 2011. ‘A Series of Unfortunate Events: Have You Got Your Mojo?’. Rhodes Journalism Review. (31) pp. 14-15.

- YOUTUBE. 2011. ‘Caught Snooping – Rear Window (7/10) Movie Clip (1954) HD’. Movieclips. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/vkwbqjb [Accessed 14/11/19]