War as Entertainment. War as change?

By Louis Izard (14th Decemeber 2019)

‘Wars are now also living room sights and sounds’ (Sontag, 2004, p.16)

‘The shock of photographed atrocities wears off with repeated viewings’ (Sontag, 1977, p.20)

It is clear that certain representations of war and suffering have become all too commonplace, particlularly in the images we see (both now and then) of the difference between coverage of the the Vietnam war (1955- 1975) and Iraq war (2003 – 2011) and they way they have been appropriated for entertainment alone.

Does this make us less or more involved? Does the power of the cinema dilute this? or are we merely living in a simulacra? Where does the photograph fit in?

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag (2004) looks into the way we view war and suffering. She proposes two central ideas on how war photography / imagery can affect a population. The first is through the media, in which mass distribution of these images of suffering cause public outrage and demand for change. While the other idea looks at the gradual erosion of compassion after repeatedly viewing these images. Essentially, she argues that ‘Such images just make us a little less able to feel, to have our conscience pricked’ (Sontag, 2004, p.94).

‘I really don’t think that a picture of an atrocity should be a good picture, a beautiful picture, a well-composed picture… It should be casually composed, hastily framed, only competently printed’ (Sischy in Lewis, 2003)

In contrast, the Vietnam war was widely photographed, and the images captured are certainly graphic to our modern eyes. This is due to the display of real and uncensored depictions of suffering from both sides, in so many different contexts.

Consider the photographs included in the music video for Buffalo Springfield (1966) For What It’s Worth below.

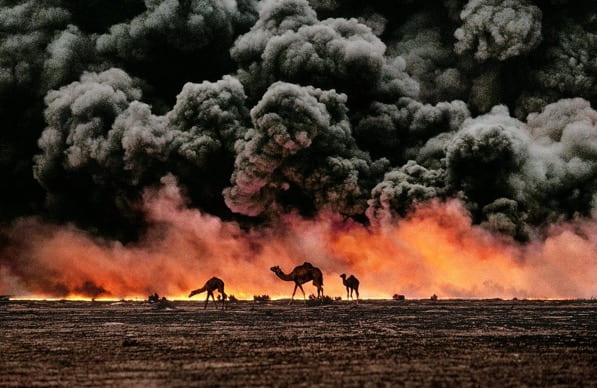

Iraq was considerably different. As Kenneth Jareke (2014) points out ‘It was one picture after another of a sunset with camels and a tank…If I don’t take pictures like these, people like my mom will think war is what they see in movies’ (Jarecke in Deghett, 2014).

Consider the film trailer for David O. Russell (2003) Three Kings below.

representations from Vietnam are more likely to depict the violence inflicted on others, whilst images of Iraq are mostly of tanks, guns and US soldiers – a particularly Western / American view of the world perhaps?

‘Baudrillard pointed out that the [Iraq] war was conducted as a media spectacle. Rehearsed as a wargame or simulation, it was then enacted for the viewing public as a simulation: as a news event, with its paraphernalia of embedded journalists and missile’s-eye-view video cameras, it was a videogame. The real violence was thoroughly overwritten by electronic narrative: by simulation’ (Poole, 2007)

So today, in our image world, and the age of the (uncensored) internet – what is the role of Citizen Journalism? As Sontag (2004) notes, ‘The less polished pictures are… [more they are] welcomed as possessing a special kind of authenticity’ (2004, p,24). Here is New York (2004) was one of the largest collaborative projects undertaken to archive the events of 9/11 but also as a celebration of a vibrant city overcoming trauma.

‘What was captured by these photographs — captured with every conceivable kind of apparatus, from Leicas and digital Nikons to homemade pinhole cameras and little plastic gizmos that schoolchildren wear on their wrists — is truly astonishing: not only grief, and shock, and courage, but a beauty that is at once infernal and profoundly uplifting. The pictures speak both to the horror of what happened on 9.11 (and is still happening), and to the way it can and must be countered by us all. They speak not with one voice, but with one purpose, saying that to make sense of this terrifying new phase in our history we must break down the barriers that divide us’ (Shulan, 2004)