MINIATURES

BA(Hons) FINE ART / FALMOUTH SCHOOL OF ART

This exhibition marks the return of the miniature to Gray’s Wharf. Fine Art students from Falmouth University have once again been invited to consider miniature-making in relation to their own contemporary practices.

Miniatures are typically characterised as tiny or petite. However, what separates the miniature from the generally small? While little things can be synonymous with kitsch and cuteness, the miniature demands a closer consideration of its diminutive stature.

It possesses a curious dissonance which stems from its duality of being at once representational yet unfamiliar, mirroring objects from our own reality while simultaneously severing any pre-conceived relationship to functionality.

Miniaturisation opens a door to a strange space of playful and inquisitive absurdity, in which a multitude of human and more-than-human ideas can be channelled and encountered anew.

A miniature within a miniature

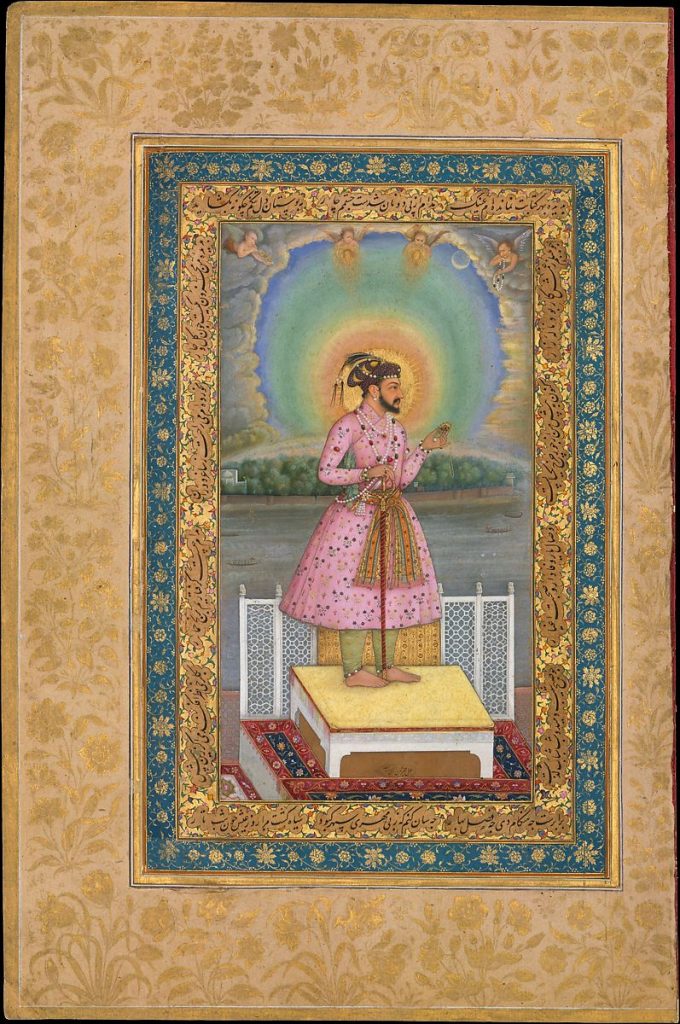

In 1628 The Mughal emperor Shah Jahan commissioned the artist Chitarman to paint his portrait in miniature. The shah is depicted holding up and contemplating a tiny portrait of himself – a miniature within a miniature. This self-regarding gaze condenses into a single tiny image the sprawling operations of imperialism. We see a ruler whose grasp on power flows from and through his exceptionalist, inflated sense of self.

This exhibition – this strange collection of little, reduced things – also contemplates the power of miniaturisation, but as an open and ongoing set of critical questions. Common to this hugely divergent range of practices on display here is a desire to subject the process of miniature-making to contemporary scrutiny and self-reflexive enquiry.

They don’t look like miniatures…

The Royal Society of Miniature Painters, Sculptors and Gravers states that the maximum dimensions for a miniature are as follows:

Rectangles and Ovals: 11.5 x 15cm

Squares: 11.5 x 11.5cm Round: 11.5cm diameter

Sculpture: should not exceed 20cm across the longest measurement

A number of projects in this exhibition clearly exceed these dimensions. Yet they still have a home in this exhibition, because even though they have not assumed a miniature form, they are nonetheless invested in exploring, thinking through and troubling the process of miniaturisation.

For example, the strange grey box over by the window (submitted to the exhibition anonymously) is a prototype for a device that miniaturises the human voice. It is an absurd construction – a shonky, makeshift prop waiting to be activated by a daft performance – but the accompanying pile of books begins to complicate the visual one-liner.

In a neoliberal society, stress/anxiety/depression are framed as individual deficiencies. Productivity is effectively privatised as a personal responsibility, and if a health episode threatens an individual’s economic activity, they are expected to seek a cure accordingly. However, medication and other treatments increasingly suppress symptoms of suffering without addressing the role capital plays in their causation.

In this context (and at a push) the grey box begins to operate as a more insidious system of control, hushing voices that do not – or cannot – consent to normative neoliberal notions of productivity and performance.

Neil Chapman’s A2 photocopy is also bigger than a typical miniature. The text on display is Neil’s attempt to re-write from memory a section of The Winter Journey by Georges Perec. Because the source material cannot be summoned in its entirety, the new text inevitably miniaturises the original. But Neil acknowledges that the deviations and elaborations he made as he miniaturised Perec’s text reveal a unique property of miniaturisation more generally: the capacity for revelation, complexity and making anew that pushes against a prevailing movement towards stasis and inertia.

… those elaborations can be seen to mobilise another logic of miniaturisation. […] When it succeeds, one of the miniature’s powers is to give rise to an explosion of potential. And that will appear marvellous because, for a moment, it delays the more fundamental cooling that all ideas, all matter, all life-forms are subject to in the long run.[1]

This takes us to the next big object in the exhibition. We can immediately say that Sonia Ahmad’s canvas miniaturises the vastness of an expanding universe. But when viewed alongside Silvija Vaitiekunaite’s video of tiny critters and assorted slithery beings, the pairing summons a seductive dialogic interplay of twinkling vibrancies that confounds our perception of scale. We are confronted with the idea that the extremes of micro and macro do not sit at opposite ends of a linear spectrum, but bend back towards each other, as if straining to touch. In moments like these, the micro becomes macro, and the macro micro.

Sonia’s piece is titled Bonded, and in front of the canvas we see two separate pieces of rock fused together into a more composite, complex proposition. In a chaotic universe bound by the laws of entropy, these little fragments have forged an attraction to each other – a tough, enduring bond. The celestial dynamics of Sonia’s piece suddenly shrink to a very human scale, alluding to the ways in which we forge intimate proximities in defiance of the gradual undoing of all matter that Neil alludes to above.

This prospect of attraction and proximity was echoed during the installation process itself. The little magnets used to position Emilija Pliaukstaite’s prints leapt repeatedly from our hands, drawn to each other by strong, invisible forces.

But while some objects attract, others repel. Aimee Shardlow’s unassuming little canvas is titled we argued…, conjuring a whiff of inevitable, endless and uncontained discord. Too often, specific arguments (even the most petty ones) play out a larger and ongoing turbulence that’s much harder to face let alone vocalise. This exemplifies another quality of miniaturision; it condenses big, devastating ideas – idea too big to hold – and gives them back to us in dimensions we’re more able to contend with.

Yay-an Davies’ miniatures perform a similar manoeuvre. They are made by fusing tiny bit of found metal hardware – nuts, bolts and screws etc – with the bronze casting process. The resulting figures populate a speculative post-human landscape in which all known life has been expunged from the planet. Yay-an fictions a future species on Earth that has somehow confused traces of pre-apocalyptic organic matter with the toxic waste left behind by humans. New creatures evolve – weird corrupted hybridisations of ancient DNA and polluted matter.

The minute scale of Yay-an’s work dictates that each figure alludes to generic rather than specific characteristics – he summons broad taxonomies and speculative ecosystems rather unique individuals. This returns us once more to the capacity of miniaturisation to summon vast, diabolical ideas. While the localised and diminutive charm of Yay-an’s practice might offer us a temporary reprieve from climate anxiety, his tiny hybridised figures still take us headlong into the unmitigated horror of unfolding global catastrophe.

Tiny things don’t get much bigger than that.

Shah Jahan

The Mughal emperor Shah Jahan was a ruthless leader who executed members his own family to secure his succession, then consolidated his power with a bloody and despotic rule. He is remembered for commissioning the iconic Taj Mahal – the marble mausoleum in which he was interned after his death in 1666.

But Shah Jahan is also responsible for a much smaller, but similarly remarkable cultural artefact. In 1628 he commissioned the artist Chitarman to paint his portrait in miniature. The shah is rendered in profile, resplendent in a bright pink jama (a long, ornate coat) a purple turban and a sparking array of bejewelment. The clouds above his head part, deferring to his radiant beauty.[2]

The tiny painting teems with a radically diverse visual language, with nods to ornate Persian calligraphy, Indian colour palettes and Flemish innovations in perspective and shading. This intricate entanglement of references very deliberately figures Shah Jahan’s efforts to position himself as an all-powerful yet cosmopolitan ‘king of kings’, presiding over a dynamic and vibrant realm.

Rendered with a brush of fine squirrel hair and framed with layers of decorative print, the exquisite allure and sheer socio-political heft of this image exemplify how a miniature’s little details can speak uniquely to massive historical and ideological discourses.

Within the painting, the emperor holds up and contemplates a tiny portrait of himself – a miniature within a miniature. The depiction of this self-regarding gaze condenses into a single tiny image the sprawling operations of imperialism. We see a ruler whose grasp on power flows from and through his exceptionalist, inflated sense of self.

This exhibition – this strange collection of little, reduced things – also contemplates the power of miniaturisation, but as an open and ongoing set of critical questions. Common to this hugely divergent range of practices on display here is a desire to subject the process of miniature-making to contemporary scrutiny and self-reflexive enquiry.

As we were installing the Miniatures exhibition, we noticed that our emerging palette was beginning to echo the prominent pinks, greens and yellows contained in the Shah Jahan miniature. This was an entirely fortuitous coincidence, but, as the installation continued, we decided to play with this relationship and draw it out into the architecture of the gallery. It feels like an apt gesture as the source material we’re referencing locates itself so strategically and self-consciously within a broad network of social, cultural and political contexts.

[1] https://scenesadventures.wordpress.com/portfolio/rewrite-elaborates/

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/04/02/arts/design/shah-jahan-chitarman.html