| Group B: Writing sample: read aloud 300-500 words discussing one displayed image\ example of practice (not your own) in relation to a specific critical discourse |

CHAPTER 2: PLACE & FOLK

SECTION 2: EXAMPLES OF LUMINESENT LORE.

CHAPTER 2: PLACE & FOLK

SECTION 2: EXAMPLES OF LUMINESENT LORE.

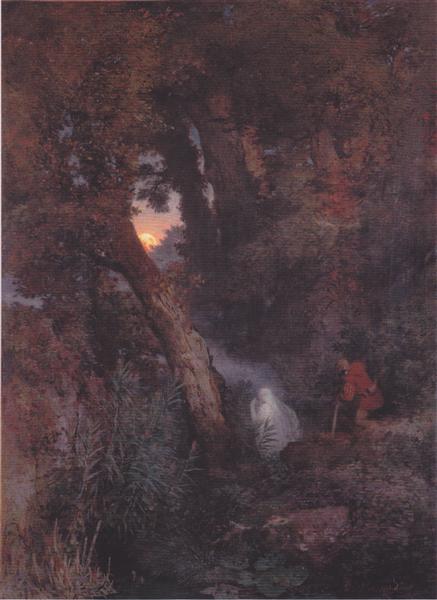

The Will O’ The Wisp is known by many names around the world: Min Min (Australia), Luz Mala (Argentina/ Uruguay), Aleya (India/ Bangladesh) and Boi-Tatá (Brazil), to name a few. Will O’ The Wisp’s roots are from ignis fatuus – fool’s fire, giving us already an insight into the doom that the lore is infamous for encouraging.

The appearance and behaviour of the Wisp can vary in all of these locations to the extent that they could be referred to as analogous to one another, rather than exact renditions. These differences range from warm to cold fire and from benign lost ancestors to malign demonic hosts. They are usually seen in areas of marshland as floating balls of fire or light. Elusive, momentary, and ethereal in appearance, its aesthetics are synonymous to the usual characteristics that make anomalous events so intriguing to people.

The phrase, which translates in modern English The Will of the Torch, with Will supposedly deriving from the proper pronoun. Although I instinctively read Will as a verb, its American counterpart is sometimes described as a Jack o’ The Lantern and has connections to the British folklore (Newell, 1904). This tells us that the Wisps have been malevolently personified, and perhaps notably so by Christian communities, which is logical when considering “apparitions and visions are inevitably interpreted, on reflection, according to their cultural contexts” (Harpur, 1994.) Fire and light are dominant within religious texts, creating all kinds of metaphors and reactions which influence its followers.

The county of Norfolk not only has several historical accounts relating to this phenomenon, but a folklore inextricably entwined with it as well. This lore is known as Lantern Man. In this personified version of a Wisp (perhaps not surprisingly considering the location) it is said that a figure wanders the Norfolk Broad fens, lantern in hand and ready to strike. The figure lures the lost and the confused to death. If the victim decides to whistle, this is said to be a particular accelerator in the Lantern Man’s murderous intentions. Their motivations (apart from a hatred of whistling) are unknown, but victims, the most famous being Joseph Bexfield (d.1809), are usually found in the marshland.

“The disposal and re-emergence of bodies may have given rise to folklore when supernatural reasons are ascribed to natural processes and the well-preserved nature of bog-bodies. Thus, folklore potentially draws on the existing liminal position of these landscapes (as uninhabitable and dangerous) and sites for the disposal of dangerous bodies, which may then return in unexpected ways.” (Flint and Jennings, 2020).

These liminal spaces, Flint and Jennings suggest, seem to be creating a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, cycle of place – narrative – place. The topography of Norfolk Broad area has a distinct lack of contour with deceptive depths, combined with the pathetic fallacy of mist. It feels simple to see how the folklore could have originally manifested for need of a cautionary tale. The landscape contained both topographical and meteorological hardships for the people in the area.

Current Essay Structure: