and, who’s In Control?

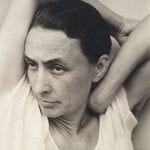

‘In front of the lens I am at the same time: the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art’ (Barthes, 1980, p.13)

This introductory session aims for participants to explore the nature of (shared) control inherent in all portraiture and the tension between photographer, sitter, the viewer who ‘interprets’ it and the context within which it is seen. In this context, it also encourages participants to reflect on a series of portraits, and also make comparisons between painted and photographic representations of ‘self’.

It poses the question ‘In what sense can a literal image express the inner world and being of an individual before the camera?’ (Clarke, 1997, p.101)

‘A face is a mask, is a lie. The face acts as a permeable membrane, a negotiated zone between the subject and the object, outside and in’ (kennedy 2006)

this session could be run in conjunction with:

- Acting the Part

- Tell Me a Story (Again)

- We are Family – post to come

‘Portraits are representations, not documents’ (West, 1997, p.53)

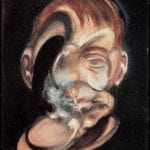

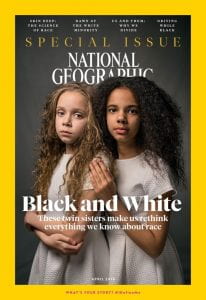

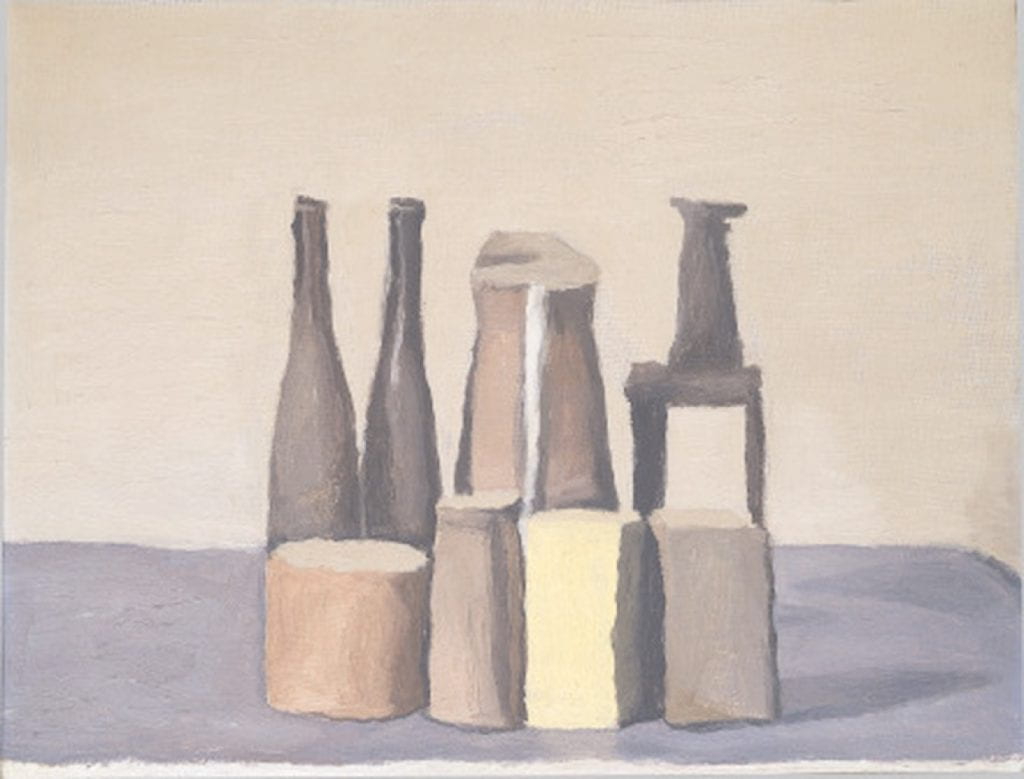

Compare: The painting and the photograph. Which do we consider the more ‘truthful’? Which subject is given the most prominence? Why?

‘The subject framing eye of the photographer is difficult to reconcile with the objectivity of the camera’s technology, it’s seemingly transparent realism of recording’ (Hutcheon, 2003, p.117)

Aims & Outcomes:

- For participants to consider the different ways in which a self might be represented.

- To consider the percieved ‘truth’ of the portrait, as an interaction between photographer, sitter and audience Who’s view is it? Is it the photographers view? Is it an ideal self? Is it a collaboration? How is it ‘read’ by its audience? What happens when we don’t know we are bring watched?

- Participant Outcome: Produce 3 10 x 8 portraits. (where the photographer is in control / the sitter is in control / a collaboration between photographer and sitter)

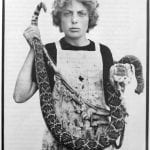

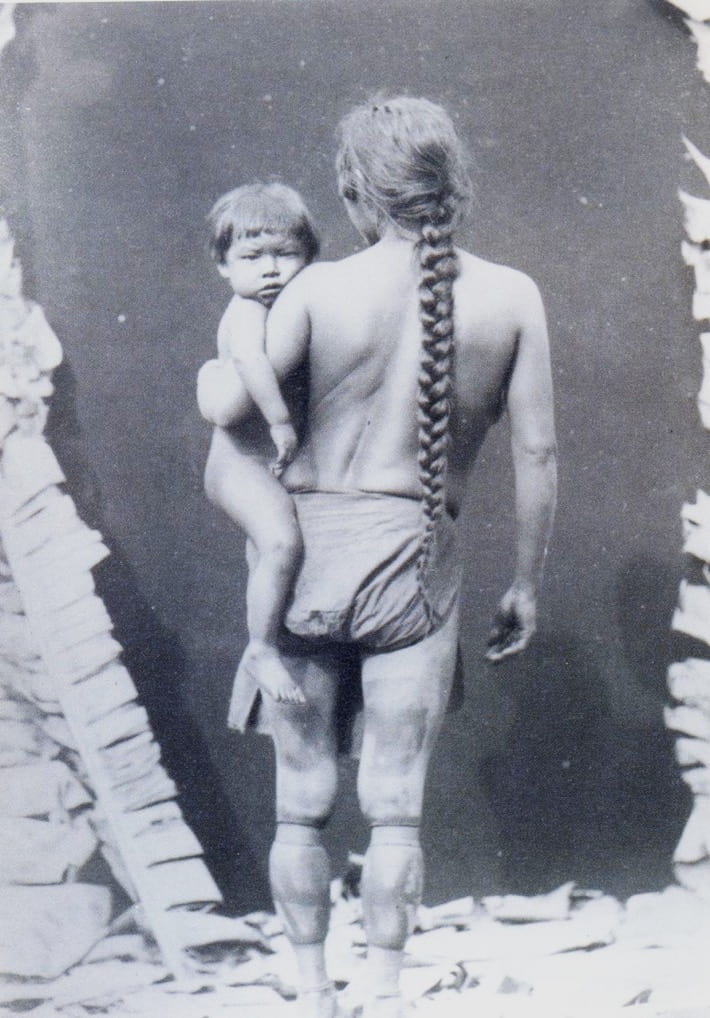

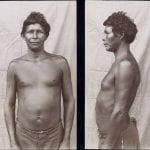

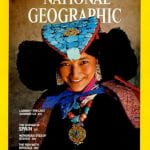

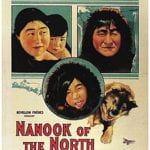

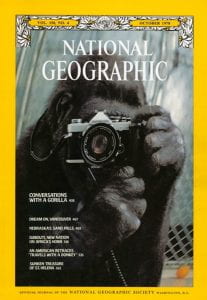

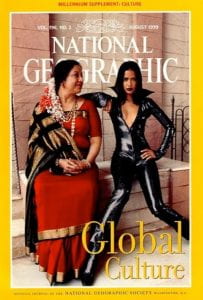

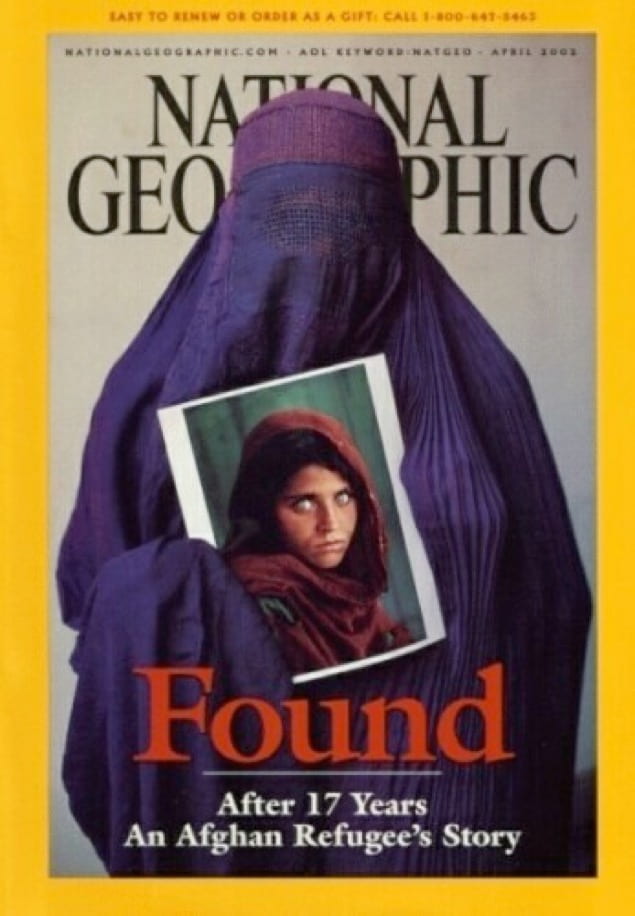

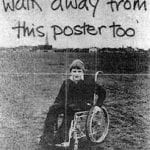

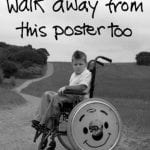

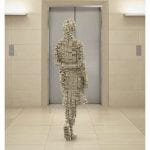

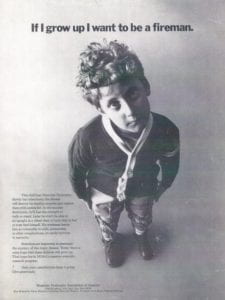

‘Think About: A percieved innocence / transparency of photographic portraits. Why might we find this image ‘grotesque’?

The grotesque effect of the photograph of the movie poster depends on the equivalence of object and its representation, of woman and picture-woman, that photography allows (Savedoff, 2000, p.51)

You will need:

- Digital cameras for all participants (and appropriate memory cards)

- Card readers

- Access to computers (or laptops)

- Flashguns (or a Studio) to practice lighting techniques

- Any props / costumes you might need

- Ideas about locations to photograph in (and how this will influence the image)

- An Introductory brief & Presentation (below) for participants to outline the ideas and provide examples

- A booked room to critique participants work (either via a projector or via print)

- Blue tack to pin the work

- Costings and Risk Assessments

‘Sometimes I think all my pictures are just pictures of me. My concern is the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may simply be my own’ (Avedon in Kozloff, 2011)

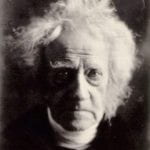

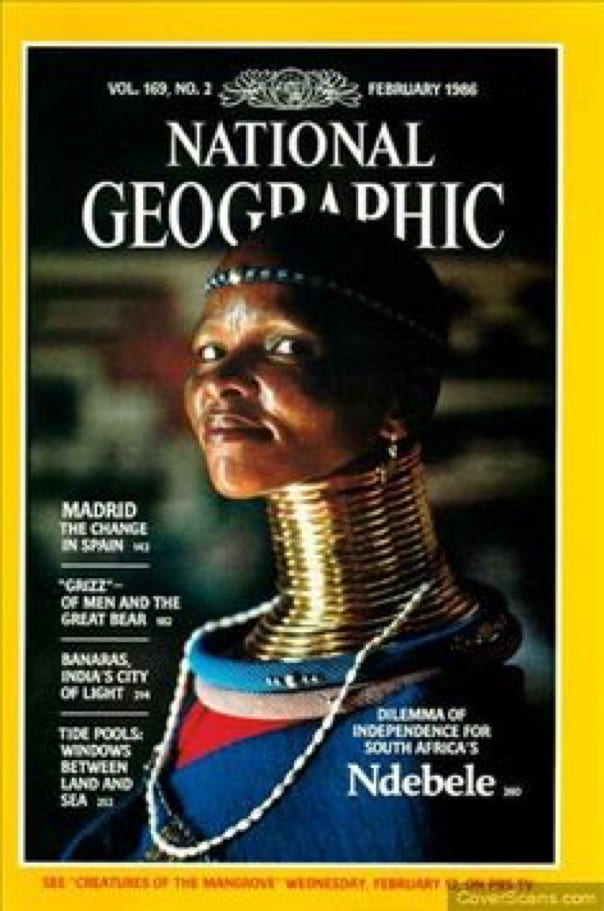

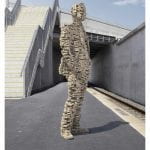

Compare: These different visions of Charles Baudelaire. Can photographers ‘create’ different selves and transform the sitter into someone else? How do we ‘read’ each image?

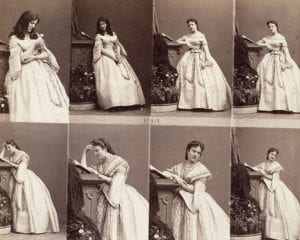

‘Once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes; I constitute myself in the process of ‘posing’, I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image’ (Barthes, 1980, p.10)

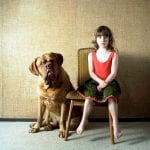

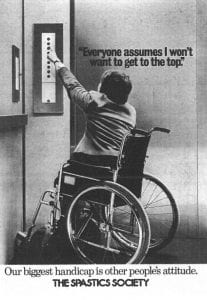

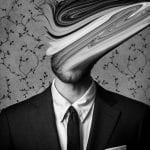

Think About: Performing for the camera. How and why do sitters perform? Do we always want an ‘idealised’ image?

‘Many people are anxious when they’re about to be photographed; not because they fear as primitives do, being violated, but because they fear the cameras disapproval – people want the idealised image’ (Sontag, 1977, p.85)

preparation work:

- Ask participants to read Richard Dorment (2003) ‘Photography in Focus: Thomas Ruff’ in The Telegraph 29th May 2003 available here

- Ask participants to explore the National Portrait Gallery resources and select one feature / practitioner of thier choice to further research available here

- Ask participants to watch Sandy Nairne (2019) Judging the BP Portrait Award and select / consider images they respond to (or not) available here

- Ask participants to identify and bring a selection of props they might need, as well as identify locations for photographing

- Ask participants if they have thier own digital cameras and cards

- Make sure you have access to computers

- Make sure there are enough team members to support participants (never assume thier prior knowledge)

- Decide whether you will project the work or print it.

- Decide whether you will introduce location / studio lighting

- If you are printing it make sure the Photo Lab are aware and be aware of timekeeping so they have space to print the work.

- *If you are running this session off campus, make sure there is access to printers or projectors

‘When I have had such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavored to do its duty towards them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man’ (Cameron in Raymond, 2017, p.34)

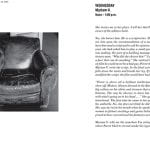

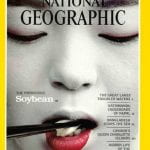

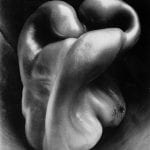

Think about: The control / vision of the photographer / the interpretation of the viewer. What does Ruff’s work really tell us about the sitter?

’Photography can only reproduce the surface of things. The same applies to a portrait. I take photos of people the same way I would take photos of a plaster bust. What people see, eventually, is only what’s already inside them’ (Ruff in Dorment, 2003)

suggested Session Outline:

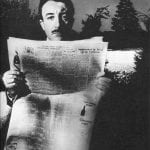

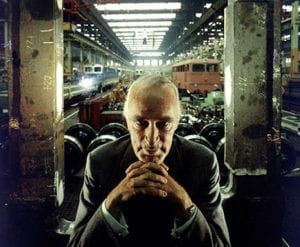

With this image in mind, ask participants to watch Arnold Newman talks about taking Alfred Krupp Portrait (2011) available here

Think about: How and why Arnold Newman has constructed this portrait the way he has / How Alfred Krupp might have wished to be represented / How we respond to it as viewers / How are public figures / celebrities represented?

- Ask participants to consider the nature of the portrait. How do they make them? Is there a difference when they are photographed as sitters? How do we ‘read’ portraits as viewers?

- What is the difference between a painted portrait and a photographed one?

- Give the Presentation below. Invite participants to compare the approaches? Who is in control? Are self portraits different? Do we all ‘perform’ in similar ways? Are photographs of celebrities merely collaborative stereotypes? Can a ‘space’ be a portrait?

- In pairs make 3 portraits:

- Take Control: The photographer has complete control over the representation of the sitter. ‘Who’ are they (percieved as)?

- Ideal Selves: The sitter has complete control over thier own representation of the sitter. ‘Who’ are they (trying to be)?

- Working Together: Photographer and sitter collaborate on the representation. What’s the difference?

- Print / Project and critique the images with these intents / aesthetics / the tensions between photographer / sitter / viewer in mind. Are they viewed in the way that photographer / sitter intended?

‘There’s a point between what you want people to know about you and what you cant help people knowing about you. And that has to do with what I’ve always called the gap between intention and effect’ (Arbus in Goldman, 1974, p.32)

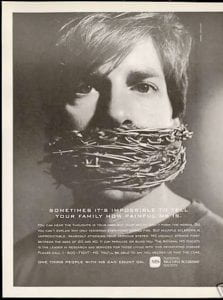

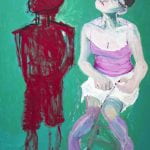

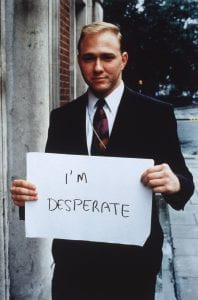

Think About: Collaborative portraits. How does Wearing’s work Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say (1992-1993) encourage us to consider the nature of the portrait?

‘[This collaboration] interrupts the logic of photo-documentary and snapshot photography by the subjects’ clear collusion and engineering of their own representation.’ (Wearing, 1997, p.3)